Here is a statistic that should concern all of us: the World Health Organization estimates that nearly two billion people globally do not have access to essential medicines. This has to do with problems in global supply chains, and also the very basic fact that most medicines are simply not accessible or affordable for the very poor. And it’s a problem that affects developing countries the most, with their large populations that live below the poverty line.

So, if you are the head of a large developing country, and you want to make medicines more affordable, what do you do?

Well, if you are Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in charge of Pakistan in the 1970s, you control the prices of drugs. It is a straightforward, kind of deal: price controls will keep drugs affordable. You can also layer in an additional set of safety regulations, which would prevent the manufacturing of substandard drugs. Thus, Pakistan was gifted the Drugs Act of 1976, which is the legislation that covers pharmaceuticals in the country to this day.

Except, in the 44 years since then, the pharmaceutical sector in Pakistan has not followed the rules. Actually, that is not quite right: a more accurate description is, in trying to circumvent the rules set by the drug act, pharmaceutical firms have tried to come up with ingenious ways of still trying to make a profit.

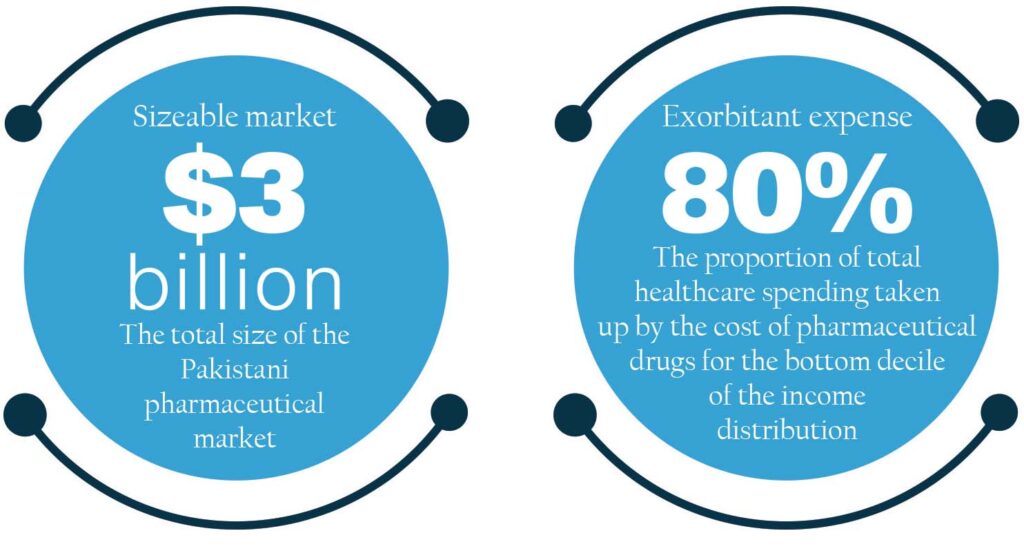

The result? Over pricing and low quality production. It has also led to a dysfunctional, inefficient sector: the top 100 firms capture a 97% market share, while around 650 firms compete for the remaining 3% market share. And the $3 billion industry has also not grown at the same pace as other sectors within manufacturing: for example, it contributed less than 1% as a share of total exports in 2019.

It is this strange turn of events – an act designed to control prices leading to overinflated prices anyway – that Kabeer Dawani and Asad Sayeed, two leading economists, examine in their working paper “Anti-corruption in Pakistan’s Pharmaceutical sector: a Political Settlement Analysis”. The two dub the current landscape as private sector corruption, or a sector involved in rule-violating and rent-seeking processes that ultimately harm Pakistani citizens.

The paper methodology is largely qualitative: between them, Dawani and Sayeed conducted 14 interviews in 2018 and 34 interviews in 2019 of the whole gamut, ranging from pharma CEOs and government health department officials to small medical store owners. They also conducted three focus group discussions in Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad.

And this is not the first time Dawani and Sayeed have dabbled in the same space together. In fact, in August 2019, the two co-authored another working paper titled: “Pakistan’s Pharmaceutical Sector: Issues of Pricing, Procurement, and the Quality of Medicines”.

While there is some overlapping material between the two papers, what makes this year’s paper particularly interesting is a brief political explanation of Pakistan. After all, the pharmaceutical sector, or the manufacturing sector does not exist in a vacuum. There are powerful players with vested interests, and all manufacturers and businessmen have to play by the rules. It is what leads to such rent-seeking behaviour in the first place.

But first, what does rent seeking mean?

Rent seeking is when a group wants to create wealth, but does not create any added productivity. There is no net gain to society or the community from the generation of this wealth; instead the group has manipulated economic resources to gain money.

This is very different from profit, in which one could argue wealth is generated because of some productive inputs, and productive outputs.

An old example of this is a feudal lord, who installs a chain across a river in his land, and then hires a collector to charge boats a fee (or rent) to lower the chain. ‘Wealth’ has been created out of nothing, even though fundamentally, the chain and the collector are basically non-productive.

In the modern world, rent seeking can look like a company lobbying the government for grants, subsidies, or tariff protection. Wait, is this legal? Well, technically yes: the company has managed to capture rents (by limiting competition), whilst not doing anything productive. It becomes corruption when a company decides to bribe the government in order to capture rents. According to the paper’s authors, private sector corruption can be defined as “rule-violating rent-seeking processes that create, capture or distort rents.”

When looking at Pakistan’s pharma sector, Dawani and Sayeed found it odd how skewed the structure was. There are 750 firms in Pakistan, but the top 50 firms account for 89% of the market, and the top 100 firms capture 97% of the market. Meanwhile, 650 firms compete for 3% of the market.

“While the pharmaceutical sector is relatively concentrated across countries, the distribution of firms in Pakistan suggests that many firms in the industry may be capturing rents,” the authors noted.

Pakistan’s political landscape

So we have explained what rent-seeking behaviour could look like: but who are these companies seeking rent from anyway?

No business in Pakistan operates in vacuum. Depending on where a business is located geographically, or who its end customer is, any business has to navigate the certain key players, and their interests.

According to Dawani and Sayeed, there are five key players in Pakistan’ political settlement: the military, political parties, religious organizations, the judiciary, and the media. Broadly speaking, the military has significant business interests, and has shaped economic outputs; while religious organizations have benefitted from links to the “non-elected state” (read: the military). The judiciary has great autonomy, and can affect public opinion, while the media alternates between aligning with political parties, religious organizations, and the military

Now, these five players (for the last 20 years at minimum) have been fighting it out for control for rents and resources, with no long term plan in sight, for the most part. As the authors note: “Pakistan’s political settlement is characterised by a high degree of fragmentation and competition between various organisations. The nature of the political settlement has meant that enforcement capabilities have remained weak and ruling coalitions have always operated on short time horizons.”

Now, while fragile political coalitions were being made, the country’s economy was still plodding along–for the most part. As the paper notes, Pakistan’s economy is characterised by low growth rates, with the manufacturing sector performing particularly abysmally. There is also a low private investment rate, which typically have been attributed to such developing country problems like infrastructure, energy crisis, violence levels etc.

However, Dawani and Sayeed take a different approach. According to them, “Pakistan has received significant geo-political rents over the last four decades and this contributed to a distortion of incentives. These rents were centrally disbursed and largely supported consumption-led growth.”

This, in turn led to growth in speculative activity, like real estate or the stock market, as compared to productive sectors, like manufacturing – because manufacturing has not been important for any of those five players mentioned above.

Indeed, within manufacturing, textiles and food processing make up a whole two thirds of value, and textiles get so much importance because they have some export value. Within manufacturing, only those sectors get any leeway that are politically close to political parties or the military: think automobiles, construction or sugar. These sectors have captured rent – even though they are not remotely competitive.

Meanwhile, electronics and pharmaceuticals are unable to capture rents. As the paper co-authors note: “Although individual firms have managed to capture rents through overpricing, low-quality production, and preferential treatment in the public procurement of medicines… the sector as a whole does not receive any significant rents.”

Wait, so do you want pharmaceuticals to capture rents? No. But it is worth pointing out that the playing field is somewhat skewed, with political patronage, and short-term thinking leading to the manufacturing sector having such a small section of the pie. If there is little room to wiggle around to begin with, you best believe the pharmaceutical sector will do its best to maximise what has been given, which is what leads to its own rent-seeking behaviour. Besides, it’s not like there will be reform of this system anytime soon: the fractured distribution of power means little to no enforcement of rules, and avoidance of actual reform.

How to price a drug in Pakistan

Broadly speaking, there are two ways in which the pharmaceutical sector tries to capture rent: by exploiting price controls, and by compromising on quality.

In the first case, Pakistan is unique in terms of how it regulates the industry via price controls. This was started through the 1976 Drug that has been the primary piece of regulation since.

One of the more interesting things about these maximum prices, is that once the price has been set, it is actually very difficult to increase it. The cost of producing a drug is not in check with the rate of inflation in the country. For example, Dawani and Sayeed point out that between 2001 and 2013 there was a price freeze, and that even when prices were increased in 2013, it was revoked after an extreme backlash.

Now, theoretically, there should be some rules-based criteria for how a maximum retail price is determined. However, practically speaking these prices are determined in an ad hoc manner, and even price revisions are also granted arbitrarily.

“A natural consequence of the discretion in pricing is that price setting and price revisions became prone to classical rent-seeking,” the authors note.

Thus, a pharmaceutical company goes out of its way to bribe a bureaucrat, in order to gain the maximum possible price to maximise its profits. The pharmaceutical company is also incentivised to do this because they know fully well that because of price rigidity, there may not be a price increase for months, if not years.

These price controls also mean that companies are simply not incentivised to produce certain drugs – and why would they?

“As costs of production rise much faster than price increases – especially with currency depreciation which makes raw material imports more expensive – margins are squeezed and the manufacture of medicines becomes unprofitable over time,” explained the authors.

This has led to an unavailability of medicines in the market: for instance, there are 80,000 drug products registered with the Drug Regulatory Association of Pakistan, but only 10,000 are manufactured.

This is basically leading to two problems: that end-consumers have to pay high prices, and also face the threat of scarcity of certain medicines. And that expenditure bit is worrying: total money spent on medicines as a share of total health expenditure jumped from 45% in 2011 to 80% in 2016 for the lowest income decile in Pakistan.

Obviously this system was untenable. In 2015, a Drug Pricing Policy was introduced (thanks to the judiciary – one of those five key players), which was then revised in 2018. Instead of arbitrarily setting maximum retail prices, the average price for a product in other South Asian countries, Bangladesh and India, was used to set the price. This kind of reference pricing was hoped to eradicate rent seeking.

But as the authors note, there was massive uproar over the very idea of raising prices of goods like medicines. The authors dub this a ‘populist’ stance that has been perpetuated by the judiciary and the media, and which political parties acquiesce to [more on this later].

Low-quality production

For a medicine to be acceptable, some good manufacturing practises need to be followed. Government data on the subject is overly optimistic, which suggests that only 1% to 5% of drugs are of poor quality.

But Dawani and Sayeed’s qualitative data, based on their focus groups, suggest that actually a lot of pharmaceutical companies are engaged in ignoring good manufacturing practices, in order to reduce costs.

This behaviour is particularly rampant in the bottom 650 firms, which explains why they still exist. Despite receiving the maximum retail price, they comprise on practises to cut costs, and thereby capture rents.

And it is not to say that the top 100 companies do not also scrimp on these regulations – even within the top 100, only 20 companies produce medicines of high enough quality to be considered for exports.

Most of this behaviour also has to do with what kind of pharmaceutical company it is. The bottom firms tend to be ‘embedded’ which is defined as those dependent on a network of personal ties and local professional experience. The top forms tend to be ‘technocratic’, often possessing international professional experience, and a tendency to follow regulation.

In short, price controls restrict the space needed to make profits, leading to some companies to compromise on quality, cut costs, and capture rents. Why should Pakistanis consume harmful, low quality drugs?

A way forward?

So, what is to be done? Dawani and Sayeed point out the obvious: remove price controls, and allow price competition. In the long run, this will lead to prices declining. There would also be a weeding out of firms, particularly in the bottom tier, who will not be able to survive the competition. This has the added advantage of removing some low quality products from the market as well.

However, there are a couple of problems with this approach, First, there is no political appetite to increase the prices; as the authors note there is consensus across the political spectrum that prices should not increase. Second, under the existing political settlement, it is not like one of the five key players have some sort of stake in pharmaceuticals and will listen to them – this is not real estate, after all. So, there is no way to exert pressure for reform. Third, regulatory efforts are unlikely to work well in developing countries, simply because there is weak enforcement.

Instead, Dawani and Sayeed come up with a completely left-field idea. They want the media to highlight how price controls are bad.

In a scathing, succinct indictment of the landscape, they write: “In the Pakistani media, the pharmaceutical sector is reported on by two desks: the economy or business desk and the city news desk. However, knowledge and capacity among reporters and editorial staff on both desks is low, which leads to uncritical journalism that does not appreciate the bigger picture around the harmful outcomes of price controls.”

If the media could exert pressure to change the narrative around price controls, then perhaps the government may follow suit. In an ideal world: “A feasible anti-corruption strategy is to build a coalition between the media and large firms. These firms can provide financial support to independent journalism schools to train journalists working in print and electronic media on the impact of price controls on social welfare, who in turn can improve the policy discourse on pricing issues.”

This is not an ideal world: we at Profit believe this is a dystopian world. Journalists do not exist to be mouthpieces of pharmaceutical companies, nor to be on their payroll. Obviously, it is somewhat ironic for us to say this, considering we just willingly devoted a few pages of magazine space to a working paper that is about price controls, but the larger point still stands.

It is not the media’s job to lobby for specific policies. That job lies with those whose interests are served by the changes they demand.

As it stands, Pakistanis are currently forced to pay over the top prices (due to the very price controls initiated to protect them), and are also forced to consume substandard medicines made by companies that the government is failing to regulate. A 44-year-old act is leading to excessive rent-seeking behaviour by an inefficient and blatantly corrupt sector, which the government will not consider changing, simply because it is worried about the optics. Yes, there is short term inertia, but up till what point will reform be avoided?

There–we suppose this article (or this paper) is doing the job for you.

Comments are closed.

Reminds me of the chanda tax the cult charges (on ALL earnings) to service maz’s very lavish lifestyle.

Mera naam shaheen adnan hin

Mujhy job ki zarurt hy

Min ne 5 tk prah hy mujhy hr kam

madican ka ata hy …

all data of this website is very useful we also know best website for madicns at visionpharma

useful information in this website all data are important we also know best website for pharmaceuticals comapnay at unichempakistan