The first thing you notice when you walk into the landa bazaar is the smell. You can’t quite call it bad, it definitely isn’t good, but it is unique. Strong, almost heady like petrol with a hint of hospital, the smell is a strange one to newcomers and a familiar one to veterans of Lahore’s famous (or infamous depending on where you’re looking from) flea market for clothes and other apparel.

That very particular landa smell comes from the fumigation that the clothes in these markets go through before they come to Pakistan and other developing countries. Most if not all of the clothes you find in these markets are hand-me-downs that have been given away in charity by people in countries like the United States, England, Australia, Japan, and South Korea.

Charities, churches, and community centers collect these clothes, and sell them to second-hand retailers. The clothes are then graded, fumigated, and shipped off to developing countries where they are sold for cheap. The market for this is massive, and Pakistan is one of the major importers of these clothes. According to a 2015 article in The Guardian, most donated clothes are exported overseas. A massive 351m kilograms of clothes (equivalent to 2.9bn T-shirts) are traded annually from Britain alone. The top five destinations are Poland, Ghana, Ukraine, Benin, and yes, Pakistan. Low-income families in these countries then go to the flea markets where these clothes end up and shop for them, particularly for warm clothes for the winters.

This has been happening for decades. But in the past few years, things in the landa have started to change. People from relatively affluent backgrounds, mostly women, have started visiting the landa and sifting through the second-hand but branded clothes and buying them in bulk. They then sell them online through Instagram, marketing themselves as sustainable fashion brands dealing in ‘pre-loved’ clothes.

The business model is enterprising and profitable, and it is also a classic example of the economic concept of arbitrage, in which you buy the same product in one market at a lower price and sell it in another market at a significantly higher price. It has also resulted in Pakistan’s imports of these hand-me-down clothes increasing at exasperating rates. While the changes in market dynamics are fascinating, there are also moral questions surrounding whether these clothes are getting to the people that they were intended for or not.

A history of the landa

This heading is admittedly a bit of a misdirection. While an anthropological or historical analysis of the landa could be done, there is very little point to it. There are loose claims that the original landa bazaar in Lahore was set-up by a woman named Linda, who was the wife of a colonial officer, and used to collect old clothes from the British to give to the locals for the winter. There is not much readily available to support this claim, but what we do know about the landa is that the items sold here go through a long journey to get there and they have some value.

The process by which they get here is quite straightforward. Charity organizations in developed countries like Oxfam, the Salvation Army, and even the Roman Catholic Church collect second-hand clothes from their donors. These donors often think that the clothes will be shipped off to the third world to be distributed freely among people that need them. This is a common misconception. Packing the clothes and distributing them would be an expensive task, so instead these charity organizations end up selling these clothes and using the money to fund other charitable activities.

To be fair to the major charities, they do not claim to give your old jeans and T-shirts away for free, but it is not readily apparent that donated clothes will be sold to traders who will then retail them.

These retailers have made a business out of hand-me-down clothing. The clothes are literally bundled up and sold at a rate of per-kilogram. These retailers then sift through the clothes, and separate torn or useless items. are recycled and used again as things like insulation materials, and soiled garments end up in landfill or incinerated. The more in-shape items end up going to flea markets within the home country, but the vast majority of the entire bulk is exported to sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, where they dominate local market stalls.

The market for this is massive. The earlier mentioned report in The Guardian estimated that globally the wholesale used clothing trade is valued at more than £2.8 billion. It is a textbook example of arbitrage, an economic concept in which an asset is bought in one market where its value is lower, and sold in another market where the value of that product is higher without any value addition. Donated clothes are sold dirt cheap in developed countries, but since they are not readily available to low-income families in the third world, their value is higher in that market. Arbitrage is essentially a risk-free way of making money by exploiting the difference between the price of a given good on two different markets.

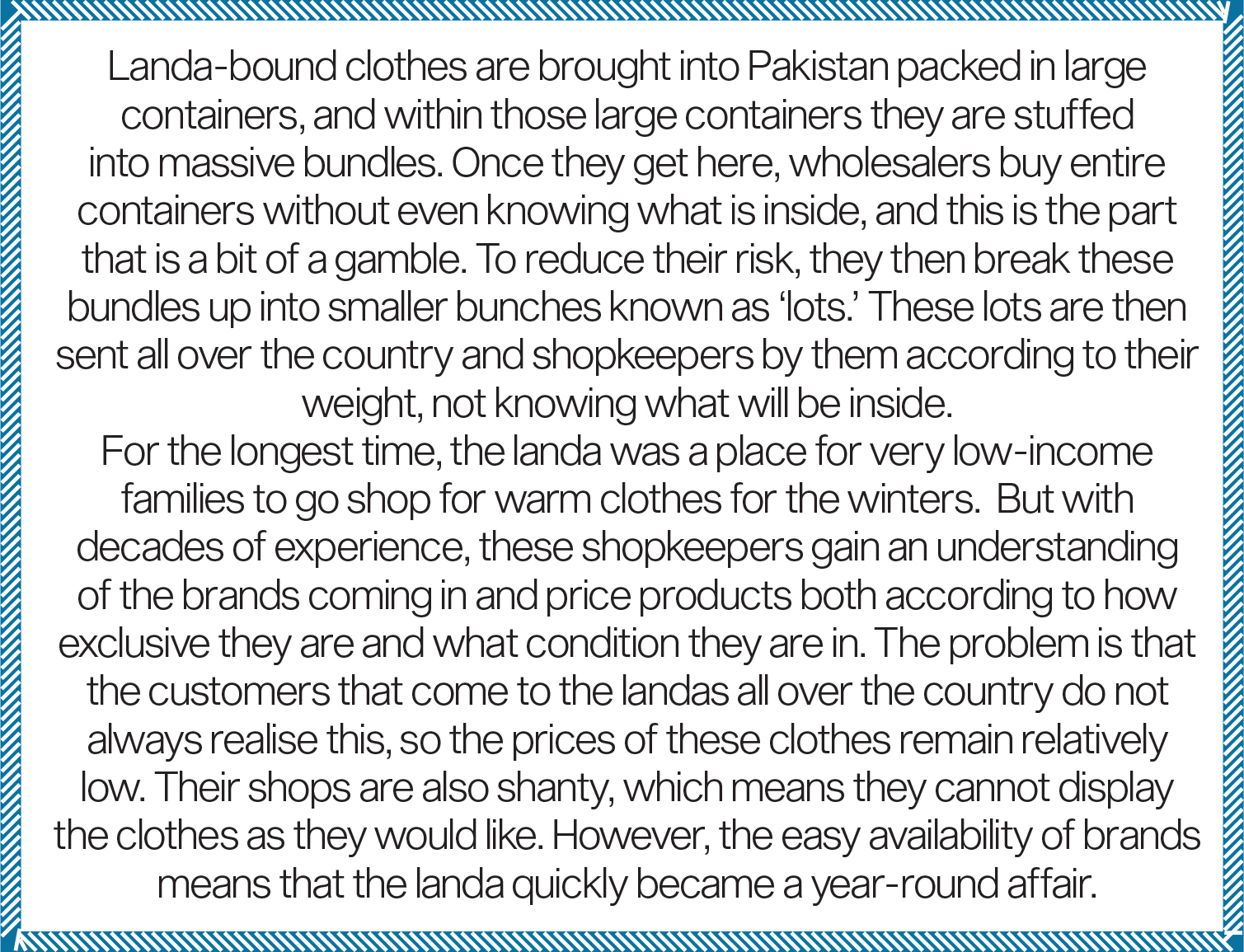

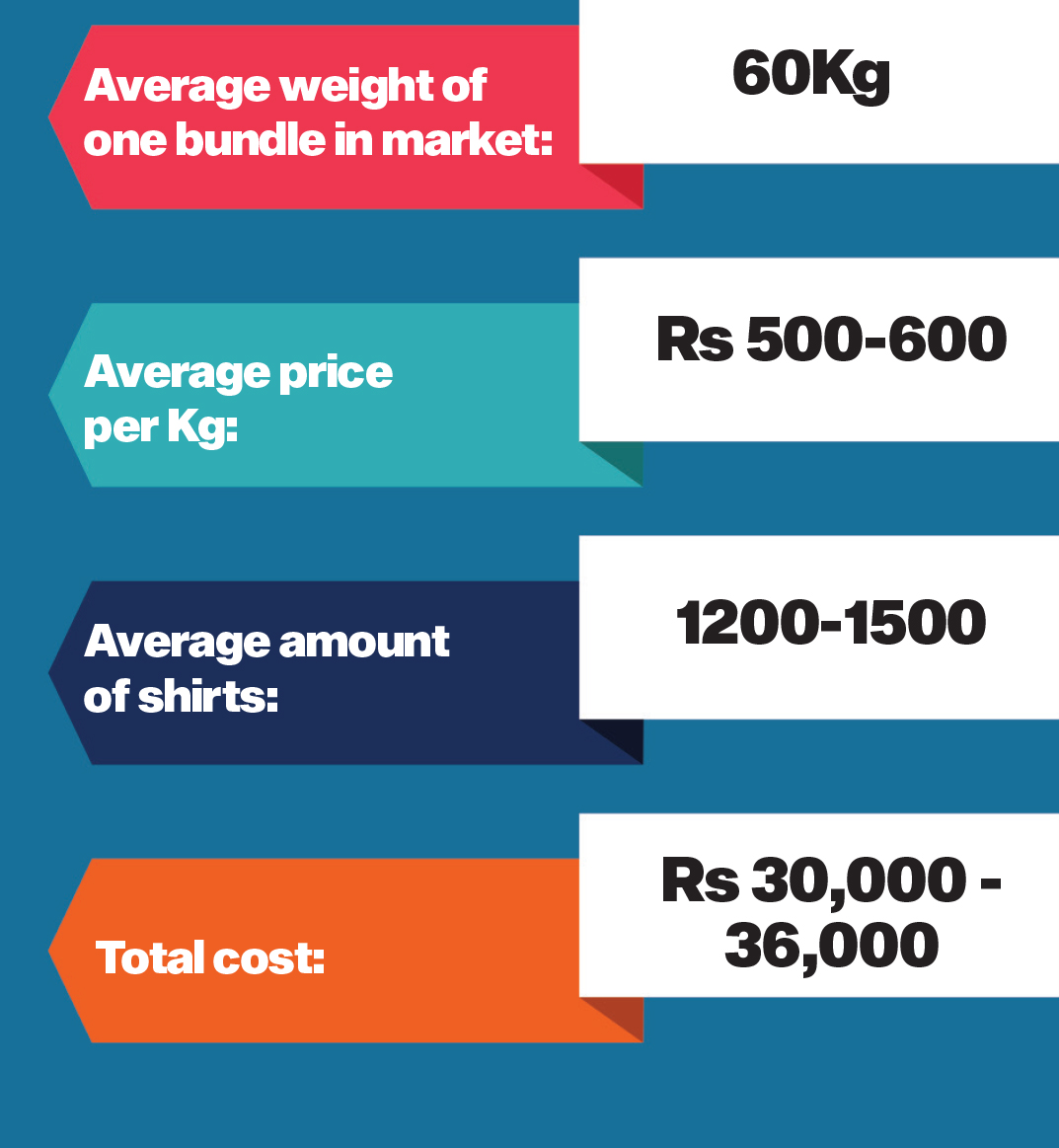

Pakistan plays a significant role in this arbitrage, and in the past few years the demand for these clothes has only increased. According to data released by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), during the last fiscal year (FY 2020-21), the import of used clothing increased by 90 per cent to $309.56 million and it weighed 732,623 metric tons. The year before that, there was an increase of 83.43 percent in terms of price. Pakistan imported 186,299 metric tons of pre-used garments during the first two months of the FY 2021-22 (July-August), which makes up for an increase of 283 per cent over the same period of last year, which translates to a spending of $79 million.

According to Mian Fayyaz, a wholesaler that deals in imported second-hand clothes and has been selling to shopkeepers in Lahore’s landa bazaar for the past three decades, the increase in demand in recent years has been because of general inflation in the country. “People used to be ashamed of buying clothes from the landa. It was taboo for the middle class, but as prices for everything skyrocket, they have no choice but to come to the landa,” he explains.

However, this cannot possibly be the only reason. There has also been increased demand, as we are arguing, from Instagram thrift stores that are buying these clothes directly from the landa and selling them online at a higher price. While they do engage in marketing these clothes, there is no value addition which essentially means that the clothes that already come in as the result of an arbitrage strategy are once again the subject or arbitrage.

First, these second-hand clothes go from the market of the developed world to the developing world where they have a higher value. Then, within these developing countries, they go from being sold to low-income families visiting the landa market to middle-class and even upper-middle class people buying it on the online market where it is sold at a higher price. In fact, an example of arbitrage often cited in textbooks is that of vintage clothing, and how a given set of old clothes might cost $50 at a thrift store or an auction, but at a vintage boutique or online, fashion conscious customers might pay $500 for the same clothes.

Enter Instagram – sanitizing the landa

Up until now we have largely discussed how these clothes get to Pakistan and where they come from, and how they are sold here by western traders as a classic arbitrage strategy. While it is not quite the same in Pakistan, since people buying these clothes through Instagram are looking for a good deal and not vintage clothing. However, the process and ethos behind these pages is fascinating.

College going students need clothes, and a lot of the time they do not have the money to buy designer clothes that are a status symbol in elite universities. So for those students on a budget that want to keep up with their richer peers, the landa has been a saviour for decades. While the clothes might not be in the best condition, they are branded, comfortable and stylish.

Middle and upper-middle class sensibilities keep people away from the landa, because the market is dingy and there is a complex about buying used clothes. However, young people are able to traverse shabby markets and have less of an ego when they are on a budget. International brands are readily available at the landa and with some washing and sprucing up, entire wardrobes can be made for dirt cheap. These clothes are often even noticed by their high-rolling peers, who recognise the brands as not easily available in Pakistan. This was all there was to it, until of course, Instagram came about.

The trajectory has actually been quite ingenious, and the way some of these pages operate is truly enterprising. “I used to get almost all of my clothes from the landa since I started studying in Karachi,” says one student from IBA that runs a thrift store on the side when she isn’t busy with her studies. “I’ve always gotten compliments from friends and strangers alike for my outfits. It isn’t just as simple as going to the flea-market, you really have to have an eye for the right stuff and that means knowing about fashion.”

According to this online thrift store owner, most of the people running such stores are women. “I didn’t have this idea immediately or on my own. I noticed other girls that went to the landa doing this on the side. They would buy 20 t-shirts for Rs 2500-3500 and sell them at Rs 500 per t-shirt and make a quick buck. People in college were going crazy at how cheap these branded products were, and they were also interested in the product since it was sustainable fashion, so I started a page of my own and pretty soon I was getting orders not just from the people around me but all the way from Lahore and Islamabad,” she explains.

It is actually very enterprising work to be going to the landa and then selling clothes from there through Instagram. People do not like going to flea-markets, so these people with an eye for fashion and an understanding of landa dynamics go to the market for them. Many of these women then buy clothes and shoes in bulk, bring them back home, clean them or fix them if they need fixing, and after that photograph them aesthetically. Some of them even model the clothes themselves or get their friends to model them for them. “There is barely any additional cost. There is the careem fare that I incur going to and from the landa, and then sometimes I wash the clothes again, and then I put them on, set my camera on timer-mode and model them myself too. I upload the pictures and start getting DMs, my customers then bank-transfer me the payment and they pay for shipping too,” says the online thrift store owner we spoke to.

“There are many ways to go about it, some people buy in bulk and others just do it less regularly whenever they go themselves. There are entire processes by which you announce that a new collection is dropping in 24 hours, and people even pre-order. It isn’t simply about bringing the clothes home, taking pictures, and selling them. It is about curating an entire experience,” she said. And indeed, a lot of these online thrift-stores have actually specialised to great extents. There are entire instagram pages dedicated to either selling t-shirts, boots, all kinds of shoes, lingerie, knick-knacks, bags, coats and all kinds of apparently items.

When you go to the landa you find everything there. Curtains, chandeliers, carpets, decoration pieces, furniture and precious crockery, then branded bags, shoes, glasses, electronic accessories and so on are all readily available. It is a simple matter of taking the plunge and going ahead with creating a page. As long as you have marketing skills and some aesthetic sense, people will want to buy it. Essentially, these enterprising young women sanitize the landa for an entire market.

They brand their products as ‘pre-loved’ or ‘rescued’ and supporting sustainable fashion, which they claim is environmentally friendly. All of this coupled with well-done photography means that middle and upper-middle class people that see these pages are more than happy to buy from them, especially since they are so cheap. However, despite the innovation of the idea and this being a near flawless arbitrage strategy, there are certain moral questions that need to be raised considering the clothes are supposed to be fulfilling a charitable function. And even more than that, the shopkeepers at the landas across the country are catching on to what is happening, and they are not happy.

A moral quandary

In 2019, Netflix launched Marie Kondo’s series “Tidying Up with Marie Kondo.” Kondo suggested making major changes and getting rid of things that you do not need. This launched a donation craze in the United States. Within several weeks of the premiere, clothing, shoes and more overwhelmed donation centers. As we have mentioned before, most people donating these clothes think that they will either go to local underprivileged people or be distributed in developing countries.

However, as mentioned earlier, the clothes are sold and then exported to countries like Pakistan. The issue here is that even though these clothes are being sold, they were still very much for low-income groups to buy. The landa was a way for the poor to have good quality clothes that would last them a long time at cheap rates. The sanitizing of these clothes and their sale to high-income or even middle-income groups presents us with a situation in which clothes are being taken away from the poor and going to the rich. It is a reverse Robin Hood scenario.

Already, even without the influx of Instagram thrift stores, the prices of these clothes have been soaring because of the general wave of inflation in the country caused by the devaluation of the Pakistani currency. In addition to this, the government has also increased duties and taxes on the import of these used clothes. Completely ignoring the class of people that buy these clothes, the government has imposed a 10 percent regulatory duty on the import of these second-hand clothes. Valuation and import duties have also been increased and the price of used items has gone up by 30 to 35 percent due to the influx of revenue.

Under the preceding government, the value of duties on a container was Rs150,000, which has increased to Rs 350,00 under the present government. Earlier, the same duty rate was levied on all used items but now the FBR (Federal Board of Revenue) has fixed separate categories for footwear, clothing, bags and leather products from which different duties are being levied. Similarly, after Covid-19, the freight from the United States increased from $2,000 to $4,000. The freight from Europe has also increased from 1,800 euros to 2,500 euros and from China it has increased from $3,000 per container to $9,000.

However, one cannot completely dismiss those engaging in the Instagram sale of these clothes as somehow stealing from the poor. Pakistan’s imports of these clothes have increased for a reason, and that is because there is more demand now and no shortage of supply – there is plenty to go around. It should also be kept in mind that while the people selling these clothes through Instagram might not be poor and could even be solidly middle-class, most of them are young people doing it out of necessity and not some misplaced sense of justice or boredom. The collections of clothes and apparel that they end up curating are creatively done, do take hard work, and the entire business model is quite enterprising. While it is a little cringe-inducing to watch these pages try to claim they are inspired by sustainable fashion and call the clothes “rescued” or “pre-loved,” one must also admire the fact that this tactic has been very successful. If these small businesses are making money, which they are, there is no real harm in this. And while the landa shop owners are not happy about this development – who would like to hear that their item is being bought from them and then being sold to someone else at a higher price – it has also spurred them into action and gotten many people in these shops to also sell their products online.

What about the shop owners?

Shams Khan of Peshawar runs a used clothing business in Lahore’s Landa Bazaar, and believes it is a very lucrative business anyway. “Be it an importer of pre-used clothes, a wholesaler, a shopkeeper or a wheelbarrow, no one has ever lost in this business. The main reason for this is that the price fix is only for the imported container and not for the pre-used clothes coming out of it. We take the pre-used clothes from the importer or wholesaler where the clothes are delivered in bundles and the price of the bundle depends on its weight, grading and type,” he explains.

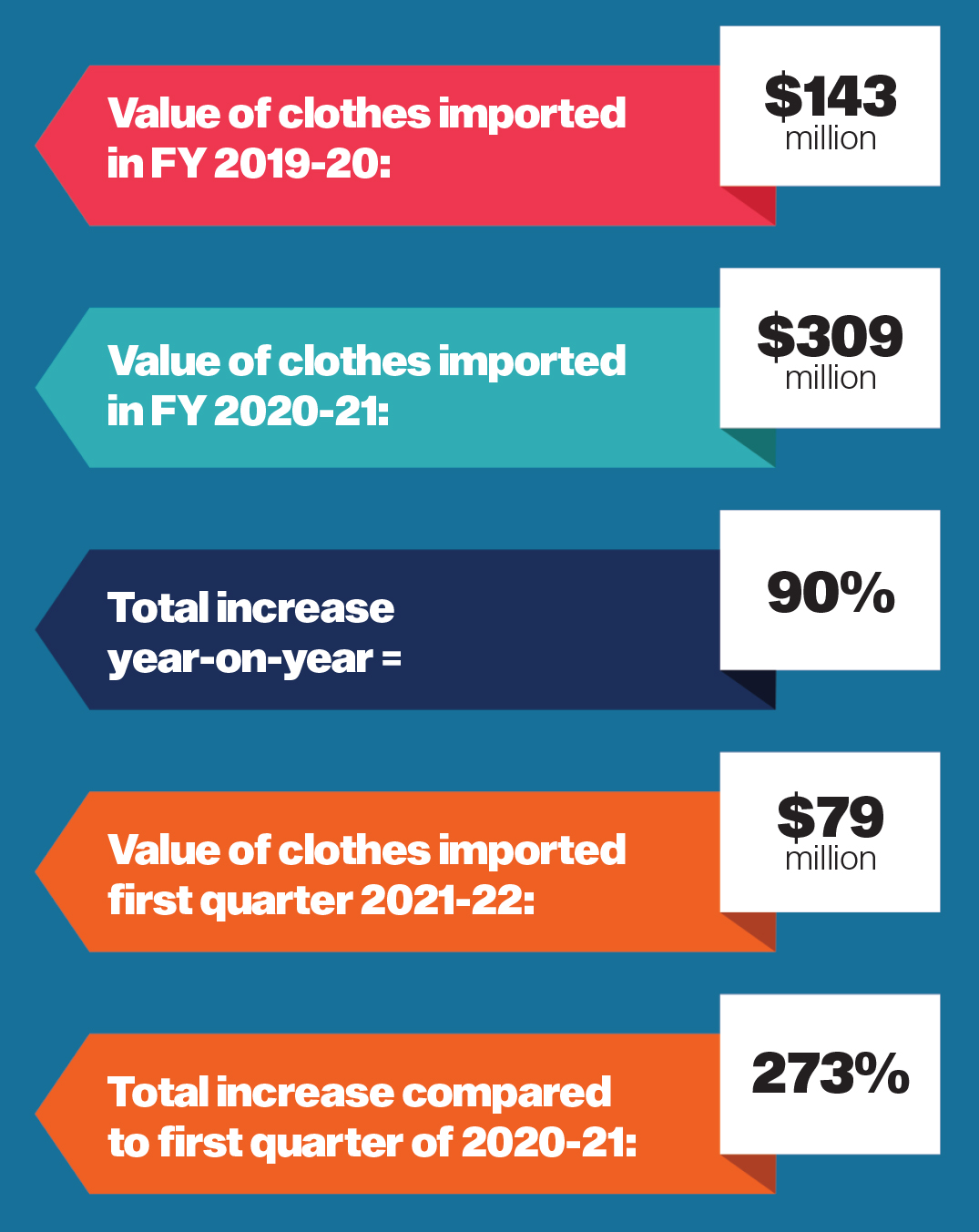

According to him, there is no way anyone can make a loss in this business because of how ridiculously cheap the second-hand clothes are. One needs to understand that these clothes are extremely undesirable in their home markets, and the traders that buy them there buy them from charities that want the masses of clothes off their hands and quickly which means they settle for very cheap rates. “Very simply speaking, if I buy a bundle that has been tagged as B category, and the bundle weighs around 60 kilograms, then I have to pay RS 500 to RS 600 per kilogram for it. So this 60Kg bundle ends up costing me around Rs 36,000. Now, we take the example of t-shirts, then it takes around 18-20 t-shirts to make one kilogram. This means for Rs 36,000 I have hypothetically bought 1200-1800 t-shirts if that is all there was in the bundle,” he explains.

“When we sort the bundle approximately 500 to 600 shirts come out that look brand new and these shirts are of famous brands and easily sell for between Rs 300 to 500. Now if I sell 500 shirts myself for Rs 300, it becomes RS 150,000 and think for yourself, I bought this bundle for 36,000, so I have more than tripled my initial investment. The other aspect is that I do not sell these 500 shirts myself but I sell them to five different shopkeepers at the rate of Rs 150 per shirt. Even then I earn Rs 75,000 and make a profit. The rest of the 1000 shirts that were not as high quality I can sell to smaller shop owners or roadside merchants. At the rate of Rs 50 per shirt, I can earn another Rs 50,000. There is no losing here.”

There is no loss here because, as we have gone to painful lengths to explain, there is no loss in arbitrage. The shirts are so dirt cheap in the countries they come from because they are considered worthless. Even if they were given a price, no one would buy them since brand new clothes are not that expensive either. They are sold cheap according to weight, and since people here don’t have access to cheap new clothes, they buy the second-hand products for significantly less than what they would have to pay for new clothes.

And while the business is thriving more than ever and profits are constant, this does not mean that the old players in the game are happy about changing times and the influx of people buying from the landa and selling these clothes online. “The landa used to be only for the poorest of the poor. They would come here not to buy brands, but military leftover coats for the winter. But as inflation has increased, people from the middle classes have been forced to turn to the landa as well. This is simply the natural trajectory of things,” explains Fayyaz. He is surprisingly accepting and nonchalant about it, a view not post shop owners in these markets hold. “The middle class, and the upper middle class also buy from here now. But the gentry considers it wrong and shameful to be in these markets, so buying these clothes online is an easy solution for them.”

However, many shopkeepers are not happy about this. They see the new entrants coming in and buying clothes from them as competition, and have also set up their own pages on Instagram and Facebook, but have been unable to find the same success since they are not as tuned into the aesthetic that the upper-middle classes crave. “A lot of shops refuse to sell to some of us,” explains the Instagram thrift store owner we spoke to before.

“They tell us since we look rich, we will go sell their clothes on the internet and make money from them. If they don’t sell to us, we will simply have to change track and buy directly from the wholesalers, but this might be difficult for a lot of the girls that are just doing this as a small side-business. But I don’t think things will take such a drastic turn just yet.