Before the super-apps of today, there were banks. They provided a number of services under one roof, including payment, clearing, verification of third-parties, stores of value, and credit. To borrow a phrase from the product world, banks handled a number of “jobs to be done”. But these were all jobs that the banking industry grew to take on. At their core, banks were, have always been, and still are, trusted brokers of data and information.

Over centuries in that role, banks created a number of products and services, and the resulting economies of scale, as well as ensuing regulation, emerged as competitive moats. But the rise of computational power and interconnectivity allows for close-to-zero marginal cost of processing information and distribution, and cheap capital finances such experiments at scale. The result is that banks can now be “unbundled”.

This is the first in a series of two articles on the potential for new digital players to disrupt Pakistan’s banking and broader financial system. Today’s piece focuses on credit and deposit products.

Deposits are the ultimate moat

Credit products are commodities. For most businesses, what matters most is the price and speed at which they can access credit. As costs of distribution (defined by the cost of getting a financial product into the hands of a customer) trend to zero with digital financial infrastructure, and costs of processing decline sharply given the volume of data that can now be routed through algorithms to provide credit decisions, marginal costs are expected to decline rapidly. Since products are relatively undifferentiated, the only differentiation will remain in the cost of capital, which will become the ultimate moat.

Most digital financial companies start in high-yielding asset classes, such as buy-now-pay-later and salary-advances, but yields for those assets fall as the market matures and competition increases. These companies finance much of their lending by taking on debt. This might be sufficient to build a billion-dollar business if Pakistan had a large enough market for high-yield products and if companies could access large domestic debt markets. Neither is true.

Cheap deposits are the key for fintechs, with credit products to ensure long-term competitiveness. Without access to deposit products, fintechs risk becoming small specialty lenders that may eventually get out-competed and out-priced by companies that can finance such products from a lower cost of capital.

Bank economics, and how digital banks will compete

The average amount in Pakistani deposit accounts at the end of 2020 was roughly Rs 280,000. That number had been growing at 5 percent CAGR over the ten years prior, so let’s assume that the average amount in a deposit account is roughly Rs 300,000 right now, or $1700. The weighted average rate on deposits was around 3.4 percent, and the weighted average lending rate was 8 percent. Let’s be generous to the bank and assume the deposit rate hasn’t changed much, but the lending rate has increased to 10 percent. Let’s also assume the bank keeps 15 percent as cash reserves (this number is likely closer to 35 percent). The bank can then expect to make USD 85 per “average” deposit account.

Incidentally, the average amount in a current account, which makes up two-thirds of all accounts, is only around Rs 150,000 or roughly $850. Using our earlier assumptions, this is around USD 43 of margin.

To be profitable on unit basis, the aggregate cost for the bank to acquire both the depositor and the borrower must be lower than that amount (i.e., $85 or $43). I doubt that’s the case for a traditional Pakistani bank, which is why — and anyone who’s tried to open a retail deposit account can attest to this — most banks couldn’t care less about deposit accounts. Because they’re simply unprofitable. Below a certain balance in a deposit account, it probably doesn’t make business sense for banks to service the customer without charging all manner of fees.

None of this should surprise anyone who has tried to access financial products in Pakistan and run into the frustrating tangle of paperwork, wet signatures and indifference. The existing physical infrastructure of banks and its associated manpower is simply too costly to provide financial services profitably to the majority of the population.

But that’s why digital financial companies have a real opportunity in Pakistan. They can acquire customers and sell products without a tremendous investment in fixed brick-and-mortar costs and at substantially lower marginal costs, allowing them to access a greater segment of the population, both as depositors and borrowers, and build a valuable business. However, digital financial services companies also risk either irrelevance or aggressive foreign expansion if they’re unable to roll out deposit products in Pakistan.

The mystery of the falling money multiplier

Let’s talk a bit about an interesting macroeconomy metric.

The money multiplier is a measure of how much money is created in response to each additional rupee created in bank reserves through central bank liquidity injections or foreign inflows. The multiplier effect happens because banks lend out a fraction of their deposits, and the money lent often ends up in another deposit account, a portion of which is lent out, and so forth.

Traditionally, the multiplier is a function of reserve requirements, i.e., the amount that the State Bank instructs the banks to keep on hand and not lend.

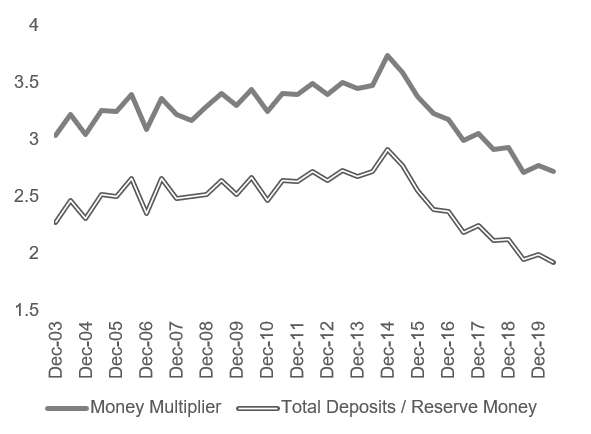

Now, the money multiplier has fallen since its peak of around 3.7 at the end of 2014 to 2.8 in the last monetary policy report. That’s a 24 percent reduction in the amount of deposits created from each rupee in reserve. This is counter-intuitive. I would have expected the multiplier to stay stable or increase slightly, since theoretically digitization makes it easier to open a new account or access bank credit.

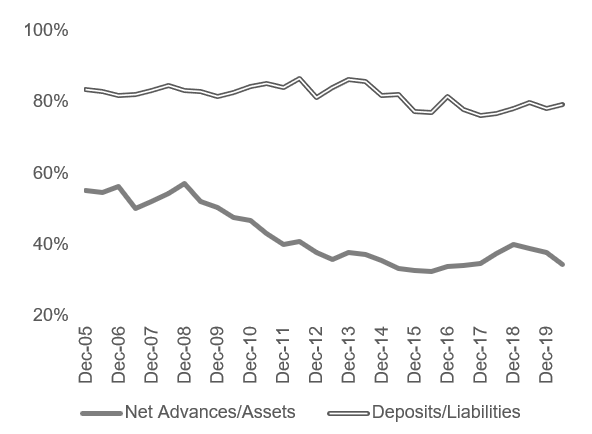

There are two possible explanations: banks could be creating less in loans/advances, and/or fewer deposits are being created. But the ratios of net advances to assets and deposits to liabilities have not changed substantially. The only explanation that remains is that the growth of banks’ balance sheets, and the financial sector broadly, has slowed down.

While this is consistent with the broader lack of financial penetration in Pakistan, I have not found an explanation for why the money multiplier has decreased. Some incomplete explanations could include the increasing allure of real estate and other assets as a substitute for deposits, the increase in anti-money laundering and know-your-customer regulations related to opening deposit accounts, or illegal capital flight.

Or perhaps the decrease in the multiplier reflects a broader secular trend that we have yet to understand. But it may be substantial for a digital bank, especially if this has to do with consumer behavior and preferences for other assets over any bank deposit.

post

Appreciate the thought provoking article. Will the absence of tangible, brick and mortar locations adversely impact the fintech/digital players in attracting the Pakistani depositor and breaking them away from mainstream banks. Secondly, low overheads will assist the digital players with a greater inclination to lend, no doubt, but legal/collection hurdles will remain that would force them towards low ticket high volume i.e. nano lending as opposed to full suite of lending products. The latter would remain with the incumbents IMO.

Nice information and this era everything is going to be digitalized