The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) recently hiked interest rates by another 125 basis points, bringing the benchmark policy rate to a nice round number of 15 percent. The increase in interest rates did not really come as a surprise, as the central bank had already embarked on a contractionary stance albeit with a significant delay. Such a stance was driven by accelerating inflation, largely a function of a rapid increase in commodity prices, global supply side constraints, access to cheap capital for longer than necessary, and a bonanza in subsidised loans through various schemes financed by the central bank.

The monetary base during the last 12 months increased by 115 percent, as more money was available in the economy chasing a finite supply of goods. This further put pressure on the value of PKR, as imports increased considerably, expanding the current account deficit, making an already precarious situation worse. Early signs of an overheated economy were apparent in the last quarter of the previous calendar year, but no one wants to end a party early, and so it continued. The party peaked when the central bank only a few months back even justified the existence of fuel subsidies, despite it being a reckless fiscal move. It may have continued even longer if commodity prices had leveled out, or gone down, but the opposite happened, as commodities across the board started reaching their multi-year highs.

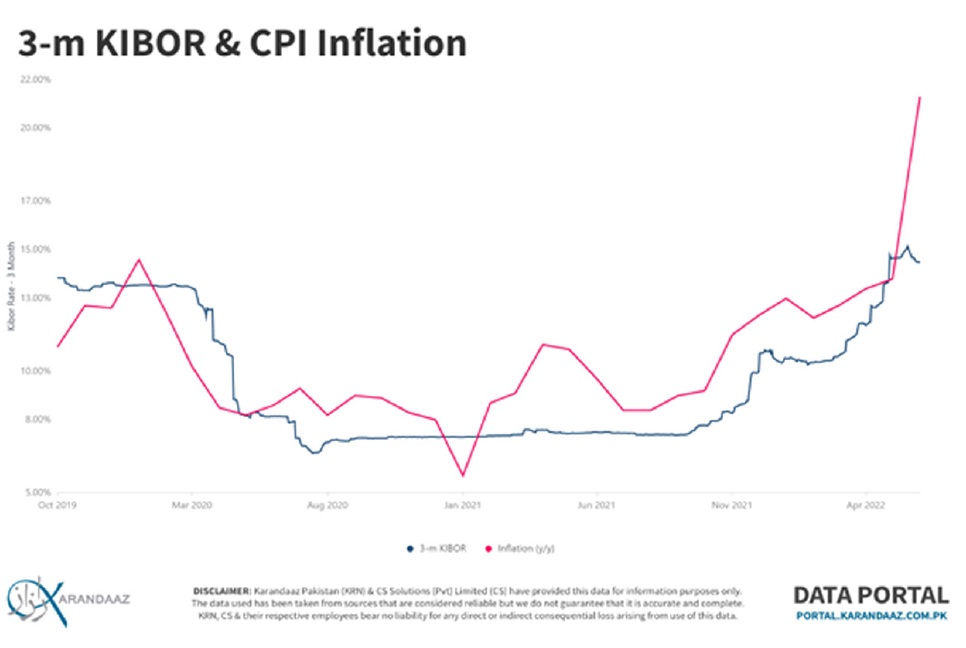

As double-digit inflation took root, it was only a matter of time before fuel subsidies were taken away, and the fiscal pains were passed on, eventually leading to the highest inflation on a monthly level in more than 13 years, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008. It was fairly obvious that inflation would exceed the 20 percent mark, and may follow the trajectory of 2008-10, but the central bank remained more reactive than proactive. Even upto December 2021, real interest rates had been negative for more than 20 months, but that still did not raise any alarm bells. The real interest rates continue to remain negative for more than 26 months now. Considering how monetary transmission mechanism, and second-round effects of inflation still need to take root, it will be another few months till inflation tapers off and a high base effect comes into play.

Anticipating higher inflation levels, and considering the government remains the largest borrower in the market, interest rates had been outpacing the policy rates with a greater margin. This was an anomaly, as lenders expected higher inflation levels, thereby having higher expectations of interest rates. Even though the central bank did try to suppress interest rates via a series of Open Market Operations, eventually the rates have converged after the recent hike.

The monetary policy statement did indicate that the “monetary policy committee will continue to carefully monitor developments affecting medium-term prospects for inflation, financial stability, and growth, and will take appropriate action to safeguard them.”

In such a scenario, one expects that the central bank would continue to maintain its hawkish stance, as it cools down the real economy, while evaluating the impact of supply-side shocks. The ability to contain supply-side shocks remains limited, but through the policy rate the central bank can ensure that inflation expectations are now de-anchored, and can be brought down as the high base effect kicks in.

We may have not peaked yet, given the delta that exists between inflation and interest rates. If commodity prices stay elevated, consequently resulting in higher inflation expectations, we may have to see another round of interest rate hikes. Meanwhile, if global recessionary pressures are kicking in, and commodities start cooling down, as they already have, particularly leading with copper prices, we may have peaked in this rate cycle. Unless of course, there is another external shock in the offing. Another round of hikes from here may have adverse consequences on the overall health of the lending portfolio of financial institutions, as default rates may increase. That in turn would affect the stability of the financial system, particularly when a few banks are already under-capitalised, and are basically ‘zombie’ banks. Another hike would have to be balanced with overall stability of the financial system, and an eventual revival.