If a bank is one of the largest banks in the country – in fact also one of the oldest banks in the country – then a certain sense of complacency can set it. In fact, it may be hard to do something that really raises eyebrows for a bank with not just such an ancient legacy but also the kind of inertia that comes with grand old institutions.

And yet, UBL managed to do just that in its half-year financials, which were released to the Pakistan Stock Exchange on August 6. Analysts dubbed it above expectations: whereas consolidated net profit in the period January to June 2020 had stood at Rs10.7 billion, it increased by 40% year-on-year to Rs15.1 billion for the same period in 2021. The resulting earnings per share shot up from Rs8.9, to Rs12.2.

And, it also managed to do this despite having less revenue during this period than in last year (Rs47.9 billion, compared to Rs49.7 billion last year).

What happened? It is mostly to do with lower privisionsing expenses – indeed, provisions have been the bane of UBL, dampening otherwise reasonable results. In this case, 2020’s half-year profit before provisions stood at Rs28 billion, compared to 2021’s half-year figure of Rs25 billion. But last year, provisions set aside stood at Rs9.9 billion, whereas this year, the bank recorded a reversal of Rs157 million. This explains the significantly higher profit for the half-year. According to AKD Securities, the bank was also helped by a higher than expected fee and commission income, at Rs7.1 billion, compared to last year’s Rs6.1 billion.

Can this spell be maintained for the remaining half year by Shahzad Dada? The new CEO was appointed in July 2020, after previously having been Standard Chartered Bank’s CEO. He replaced Sima Kamil, who completed her three year term in July 2020, and is now the deputy governor of the State Bank of Pakistan.

It is not like the bank has not done well; indeed, it has ever increasing deposits. But in the last few years it has also not done spectacularly well, and perhaps some reversal is needed.

First, some context. UBL was founded by Agha Hasan Abedi in 1959, but was nationalized by the government in 1974. Then, in 2002, the bank was sold to Bestway and the Abu Dhabi Group. The bank continues to be a subsidiary of Bestway (Holdings) Limited, a wholly owned subsidiary of Bestway Group Limited, founded by British-Pakistani Sir Mohammad Anwer Parvez. The man has been the chairman of the board of directors since December 2013. He himself started his career in the food business in 1963, when he opened a convenience store in London, before venturing into wholesale business in 1976, and has been responsible for growing Bestway Group into the 9th largest family business in the UK. In Pakistan, the group has invested in cement (the 2nd largest cement producer in Pakistan), and in banking, with UBL the crown jewel of the group’s investments in Pakistan. As of 2020, the bank operates 1,356 branches inside Pakistan, and 14 branches outside Pakistan.

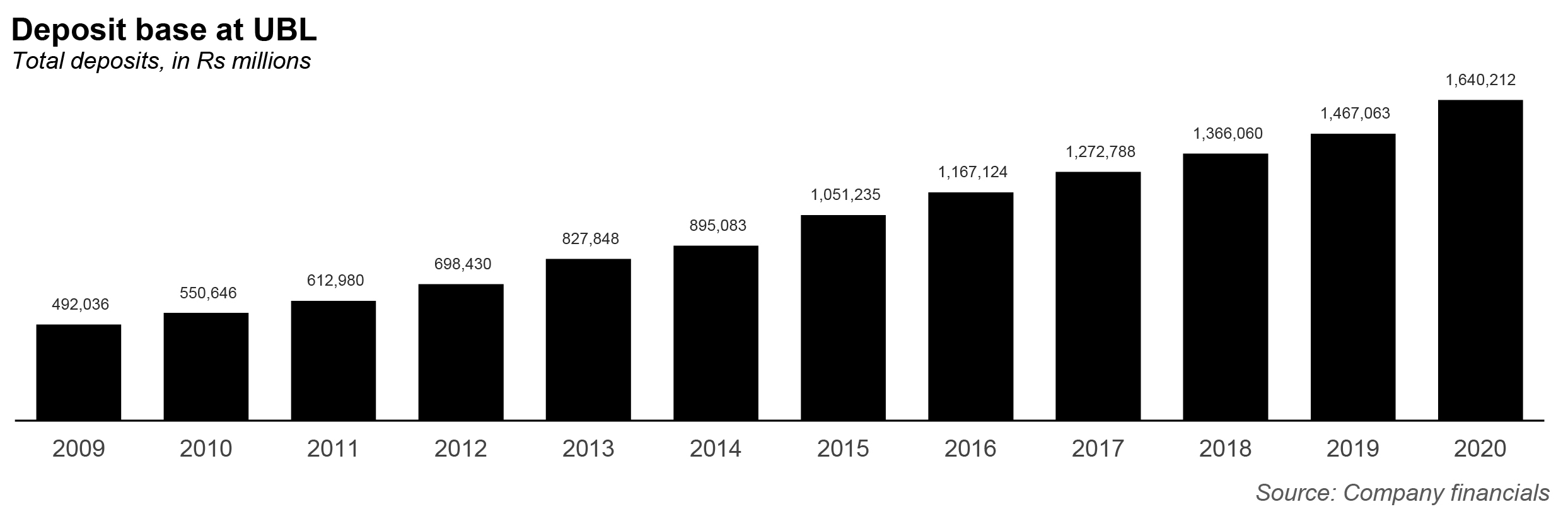

What has the last decade looked like for the bank? First up, the bank’s deposits have been steadily increasing since 2009, when deposits stood at Rs492 billion. In particular, deposits grew 18.5% year-on-year in 2013, and at 17.4% year-on-year in 2015. Deposits crossed the Rs600 billion mark in 2011, and the Rs1,000 billion mark in 2015, and finally, crossed the Rs1,400 billion mark in 2019.

If one looks at the deposits as a share of the total deposits in the banking industry, UBL’s share has stayed remarkably consistent. In 2009, the market share stood at 11.4%, the highest share it would ever have; it then fluctuated between the 10% to 11% range for the next decade. Only in 2020, did its market share dip to 9.2% – despite its highest ever deposits in 2020. If one looks at the compounded annual growth rate for deposits for the five year period between 2015 and 2020, for UBL, that figure is at 9.31%, which is much lower than the industry average for the same period, at 13.95%.

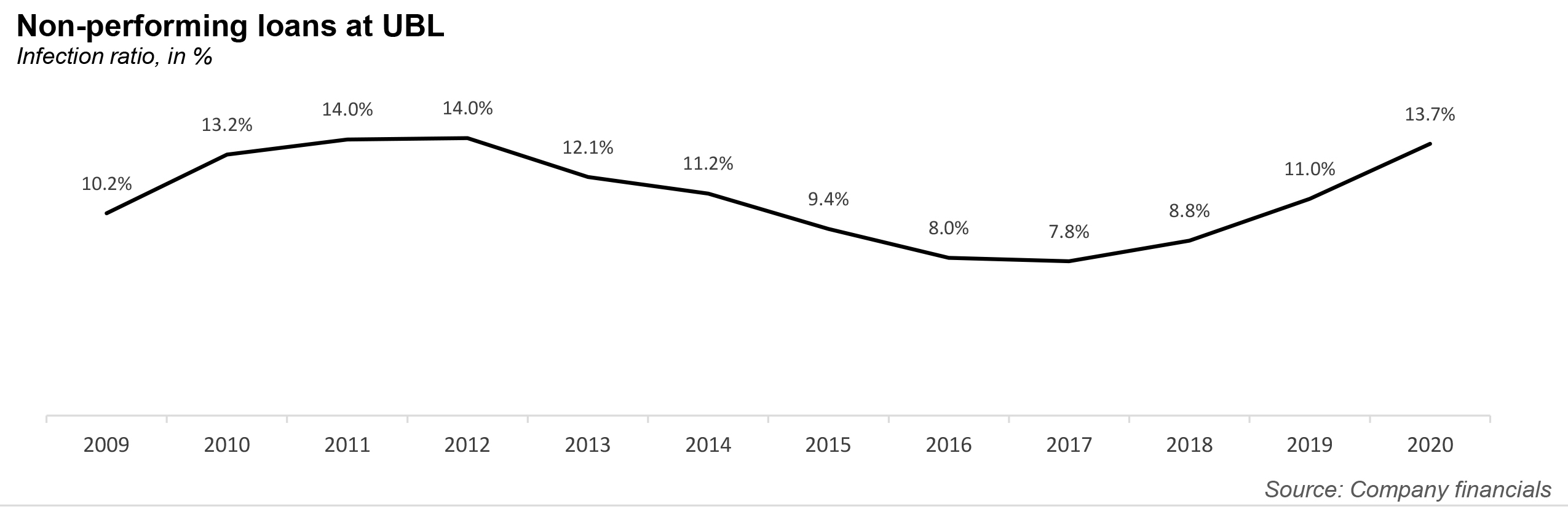

The bank’s non performing loans have been a definite problem area – though to its credit, the bank’s ratio of the non performing loans to gross advances has been either lower than the industry average between 2009 to 2017. Only in 2018 was a discrepancy seen (8.8% compared to the industry’s 8.0%). The bank’s infection ratio rose between 2009 and 2012, peaking at 14%, before falling steadily to 7.8% in 2017. Since then, the ratio has been climbing back to 2012 era rates, at 13.7% in 2020. This would explain the substantial pirivionsing set aside in recent years.

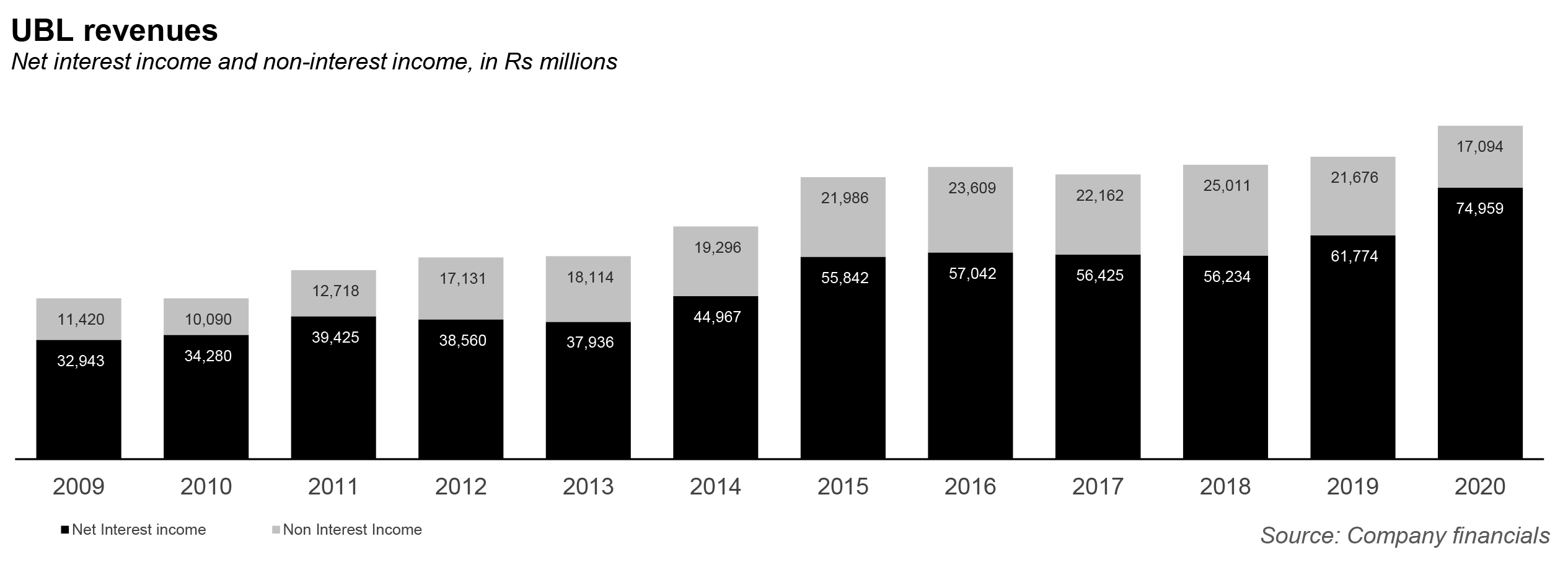

Between 2009 and 2014, UBL saw its revenues remain steady, and then jump to a new level in 2015. Net interest income remained steady in the Rs30 billion ball-park range for most of the early 2010s, before remaining steady ain the Rs50 billion range between 2015 and 2018. Meanwhile, non-interest income has remained consistently in the Rs20 billion range more or less for the last five years.

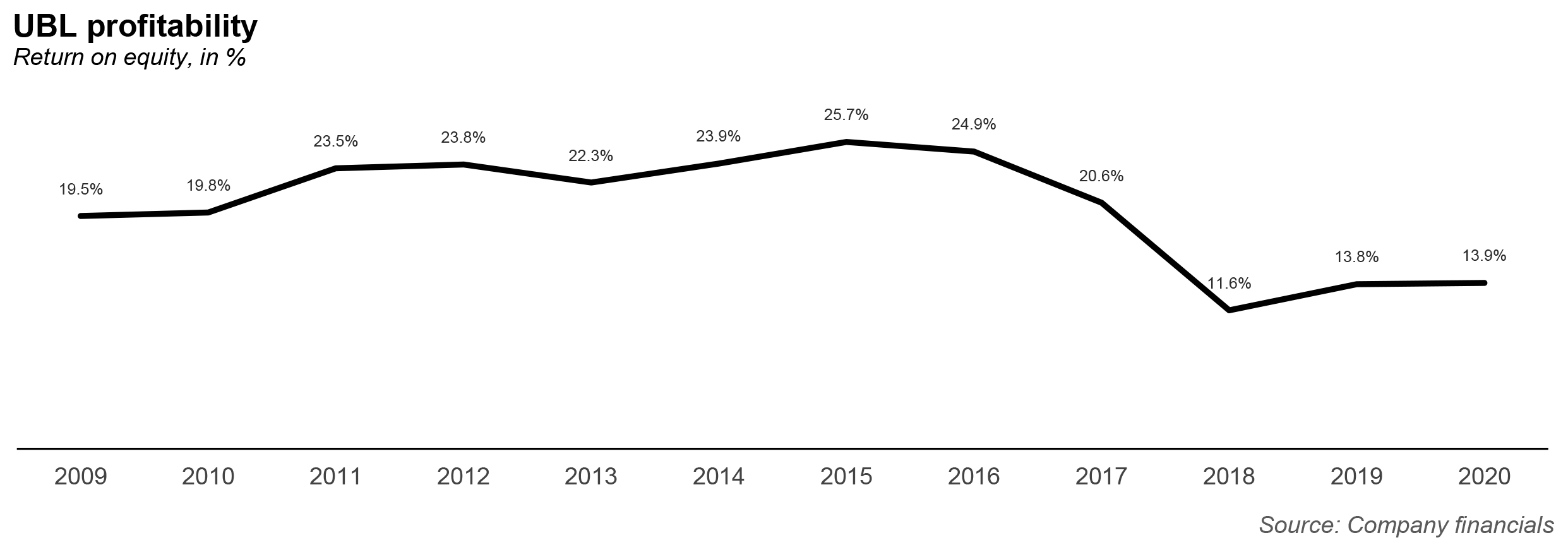

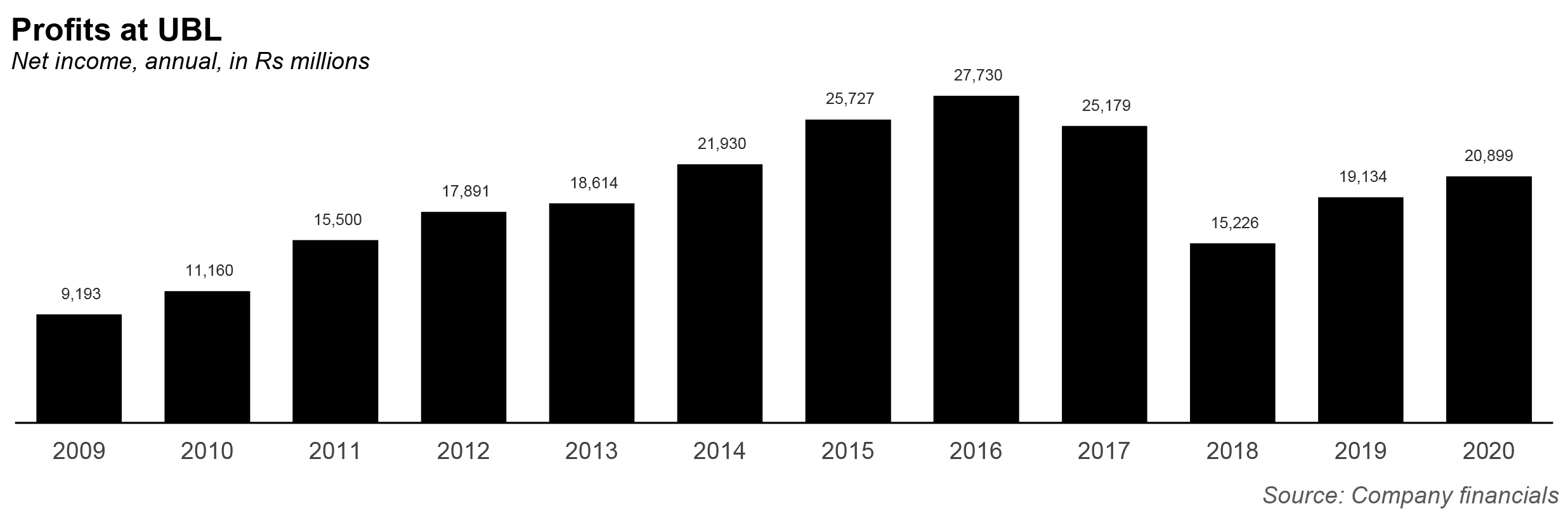

This slow and steady approach has yielded somewhat unexpected profits. Net income steadily rose from Rs9 billion in 2009, to Rs27 billion in 2016. But it fell from there, to Rs25 billion in 2017, to Rs15 billion in 2018 – the lowest it has been since 2011. Net income has risen form there to Rs20 billion in 2020. Once can see this reflected in the ROE, which is an indication of financial health (basically, how effectively management is using a company’s assets to create profits). The bank’s unusually high ROE hovered around the 25% range, before hurtling downwards to 11.6% in 2018, and just 13.9% in 2020.

Can 2021 be the year these figures reverse? Certainly, eyes will be on Dada to make that change possible – as long as provisions don’t loom in the future.