On the surface, Fauji Cement seems like a success story: in the generally bad spell the cement industry seems stuck in, Fauji Cement stands out as debt-free, with lower finance costs than its peers. It even managed to have gross margins of 14% in fiscal year 2019, which is much higher than its competitors average of 2-4%, and second only to Lucky Cement, at 15%.

So what is the problem? There are several problems actually, if one reads investment bank EFG Hermes’ latest report issued to clients on February 14.

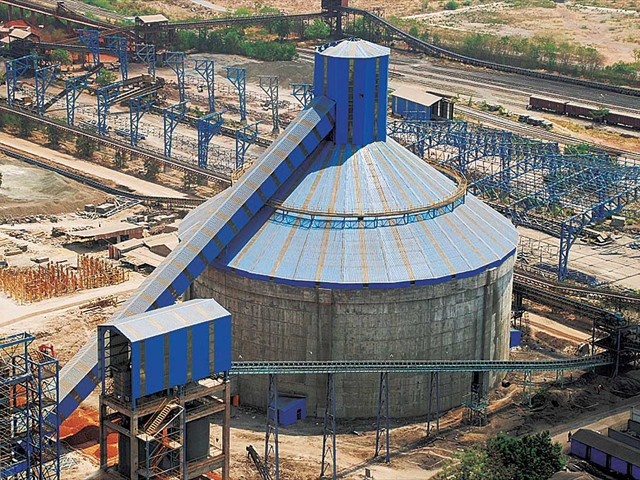

Fauji Cement managed to post better results than its peers because it has, essentially, refused to expand. In the short run, this is a ‘blessing in disguise’, but it will hurt the company in the long run, argues research analyst Jawad Shamim.

Whenever the cyclical recovery kicks in, Fauji’s competitors will have a greater capacity to cater to demand because they expanded much earlier (most expanded in the years between 2006 and 2009). If Fauji was to play catch up, it would have to buy a plant at the exchange rate Rs155 to a dollar, as opposed to the earlier Rs115 to a dollar. Then of course, the construction time of the plant itself, of around 30 to 36 months, would eat into the recovery cycle period – which means any expected benefit will bypass Fauji completely.

This lack of operational expansion is actually quite a big problem. Fauji underinvested in cost-efficient projects like captive and waste-heat power plants. Its upcoming 2.5-megawatt (MW) solar plant simply does not add much. This means that Fauji is over dependent on the grid (deriving 57% of its power from the grid in 2019). Any electricity tariff hike will severely impact the over exposed cement company.

The report also dubbed Fauji’s export business as ‘unexciting’, especially after the closure of exports to India.

Meanwhile, the rest of the cement industry has expanded, almost to the point of being oversupplied, which means that Fauji’s share of the market is also set to decline. Shamim expects the local market share to drop from its average of 7.5% during 2017 and 2019, to 5.2% by 2024.

This will translate into lower volumes for Fauji Cement: Shamim expects dispatches to decline 6% per annum over 2020 and 2021, with utilisation to decrease to 80% (compare that to the average of 91% between 2018 and 2019).

In short, this gloomy outlook means predictably less earnings. “We cut our fiscal year 2020-2022 earnings by 41% on average on weaker margins and lower market share. We lower our target price for the stock to Rs13.0,” the report says.

EFG Hermes is categorical about who to watch out for instead: “We, therefore, prefer better-equipped cement names – Lucky Cement and Maple Leaf Cement Factory – as a better way to play the cycle.”

Part of the issue for Fauji Cement relative to its peers in the cement industry may be the dividend bias that the company’s holding group – the Fauji Foundation – has from some of its larger businesses such as Fauji Cement and Fauji Fertilizers.

There are five things that a company can do with its after-tax profits, each of which has different consequences for the company’s risk profile and growth prospects.

- Capital expenditures

- Cash reserves for a rainy day

- Mergers and acquisitions

- Dividend payouts

- Share buybacks

Given the mandate of the Fauji Foundation to generate cash to be distributed to orphans and widows of fallen soldiers, the foundation often ends up requiring its portfolio companies to pay out significantly larger sums of money in dividends than other investors might. As a result, comparatively little is left for capacity expansion, unlike its competitors, which are freer to reinvest their profits without necessarily having a strong mandate to deliver cash dividends.

Over time, however, the Fauji Foundation may need to find a better balance between those two mandates. It cannot afford to have its significant investment in Fauji Cement continue to lose market share, and eventually erode its ability to generate cash flow in the future for the sake of getting cash dividends now.

Pakistan’s cement industry is a highly competitive one, where the struggle to gain market share gets particularly cut-throat. While there have been multiple attempts to organise it into an oligopolistic cartel – like the sugar industry – those attempts invariably fail to keep the industry united on a single approach for very long.

Over the next few years, the government of Pakistan is expected to resume its spending on building up the country’s physical infrastructure, which will require an expansion in the amount of cement consumed in the economy. In addition demand for housing continues to rise throughout the country, and real estate developers are putting up increasingly sophisticated development in a greater number of cities.

All of that portends well for cement manufacturers more broadly, but especially for those who have invested in expanding their capacity to meet rising demand from their existing customers. Those who find themselves constrained – such as Fauji Cement – may find themselves locked out of the market.

The answer to the conundrum is in the article itself: Fauji Cement which is in comparatively good financial shape should go for an acquisition and buy out one of its weaker competitors, thus increasing its capacity and market share.

[…] post Faltering Fauji: why a lack of expansion will hurt the cement company in the long run appeared first on Profit by Pakistan […]

Comments are closed.