To have any chance of success in business in Pakistan – especially in a sector dominated by large, powerful, and well-entrenched players – one of the most underrated qualities in a startup founder is an understanding of politics. Not politics as in “who will win the next election”. Politics as in “what do people say they want, what do they actually want, and what can I offer them to get them to do what I want.”

Tech investing in Pakistan is having a banner year. Pakistani startups have raised $82 million in just the first half of 2021 according to data from i2i Ventures, a venture capital fund, or only slightly less than the total amount of venture funding for the preceding three years combined. And within that, fintech has a significant share, accounting for approximately $35 million of the total funding raised so far this year. Among those investments is the current record-holder for the largest ever pre-seed fundraising round by a Pakistani startup: the $5.5 million raised by TAG, a neobank.

All of that money has been invested on the basis of a simple premise: that Pakistani finance is about to be transformed over the course of the next decade, and that it will be tech startups that serve as the catalyst for that transformation. One hopes for the sake of those investors that the founders of those Pakistani fintech startups have a clear sense of the politics of the industry they have decided to take the leap into.

This is not a story about who is building what in Pakistani fintech. That would be the kind of simple survey even Dawn is capable of offering. It is instead a story about one question above all else: can the fintech startups displace the banks as the dominant force in Pakistani finance? If yes, how? If not, why not?

Of course, that question is somewhat open-ended, so we can narrow it down somewhat more. In the next ten years, will there be one or two fintech companies that have a valuation that exceeds the market capitalization of at least one of the Big Five banks? Highly probable. In ten years, will one of the fintech companies have a deposit base larger than one of the Big Five banks? Possible, but highly unlikely.

We will first examine the scope of the opportunity in fintech. We will then look at the current set of challenges that the financial services industry faces, which parts fintech can help solve, and which ones it cannot. We will then conclude with an assessment of what might be an optimal strategy for startups in this space.

One point of clarification: while fintech is a very broad term, this particular story is concerned almost entirely with payments, neobanking (both deposits and lending), and wealthtech. Left out is any mention of insuretech, APIs and other infrastructure players. The dynamics of those markets are very different from the ones discussed here.

(Disclosure: the author of this story is also the founder and CEO of Elphinstone, a wealthtech startup that is registered as a Securities Advisor with the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan.)

Electronic money: why the opportunity exists in the first place

Within fintech, there is a distinction between the tech startups that enable business online (the payments companies) and the startups that engage in the business of providing financial services online (neobanks, wealthtech). The existence of the former is a precondition for the existence of the latter. And on that front, the data is quite promising. While Pakistanis use conventional offline means of payments as their predominant use of money now, the adoption rates towards electronic money are quite rapid.

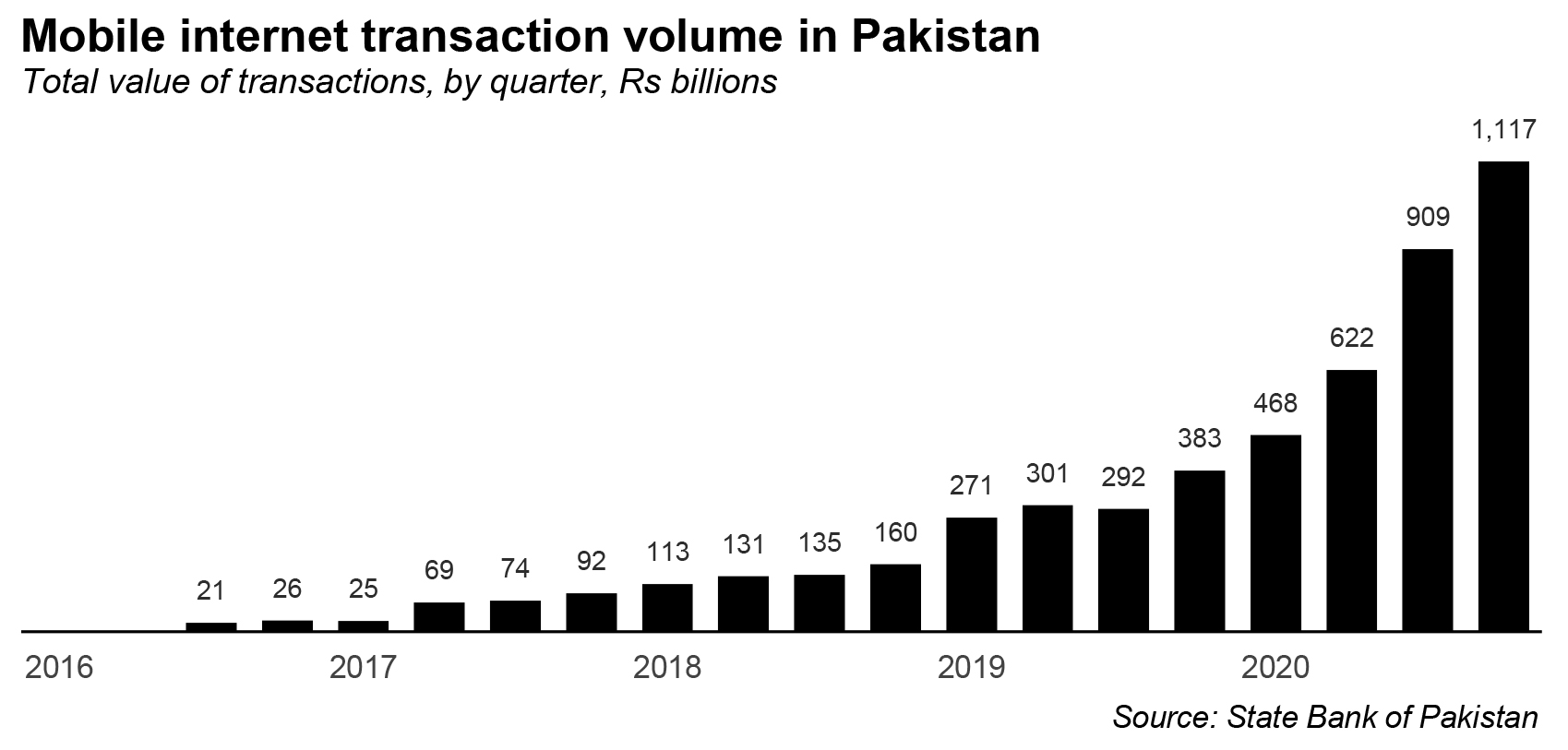

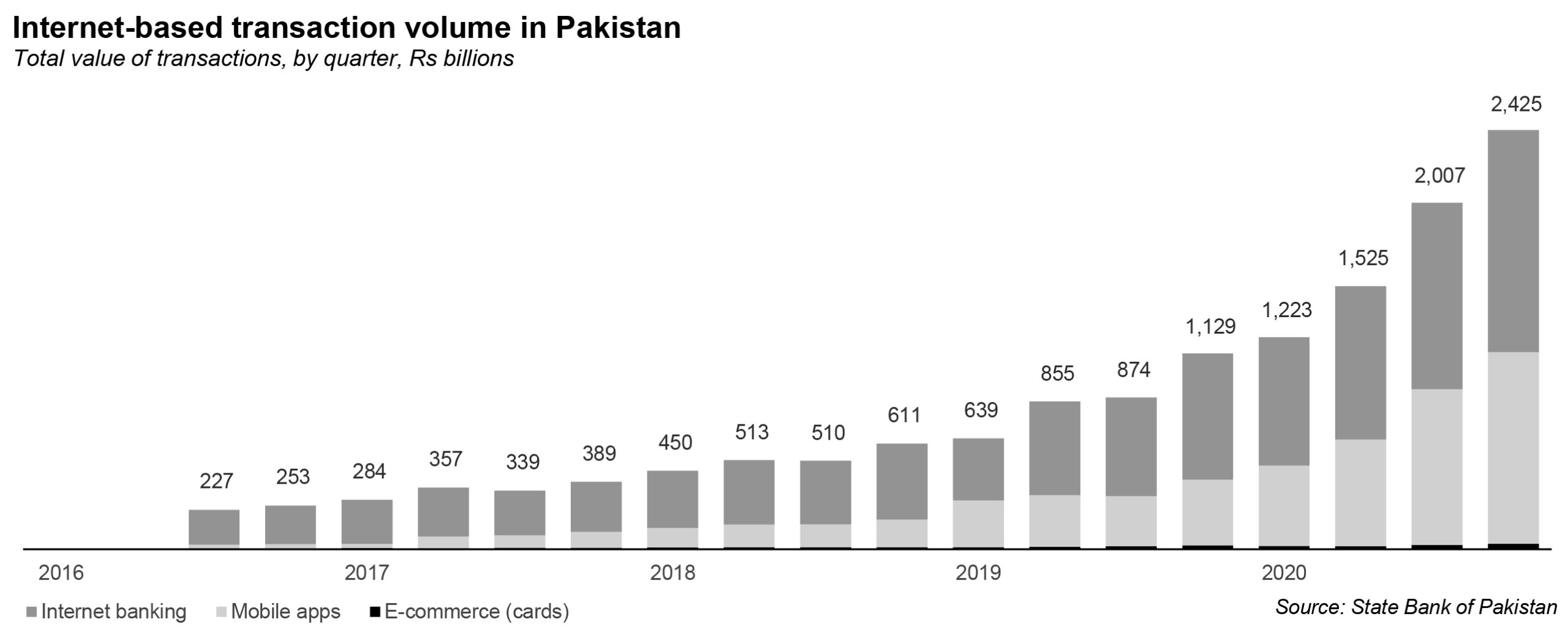

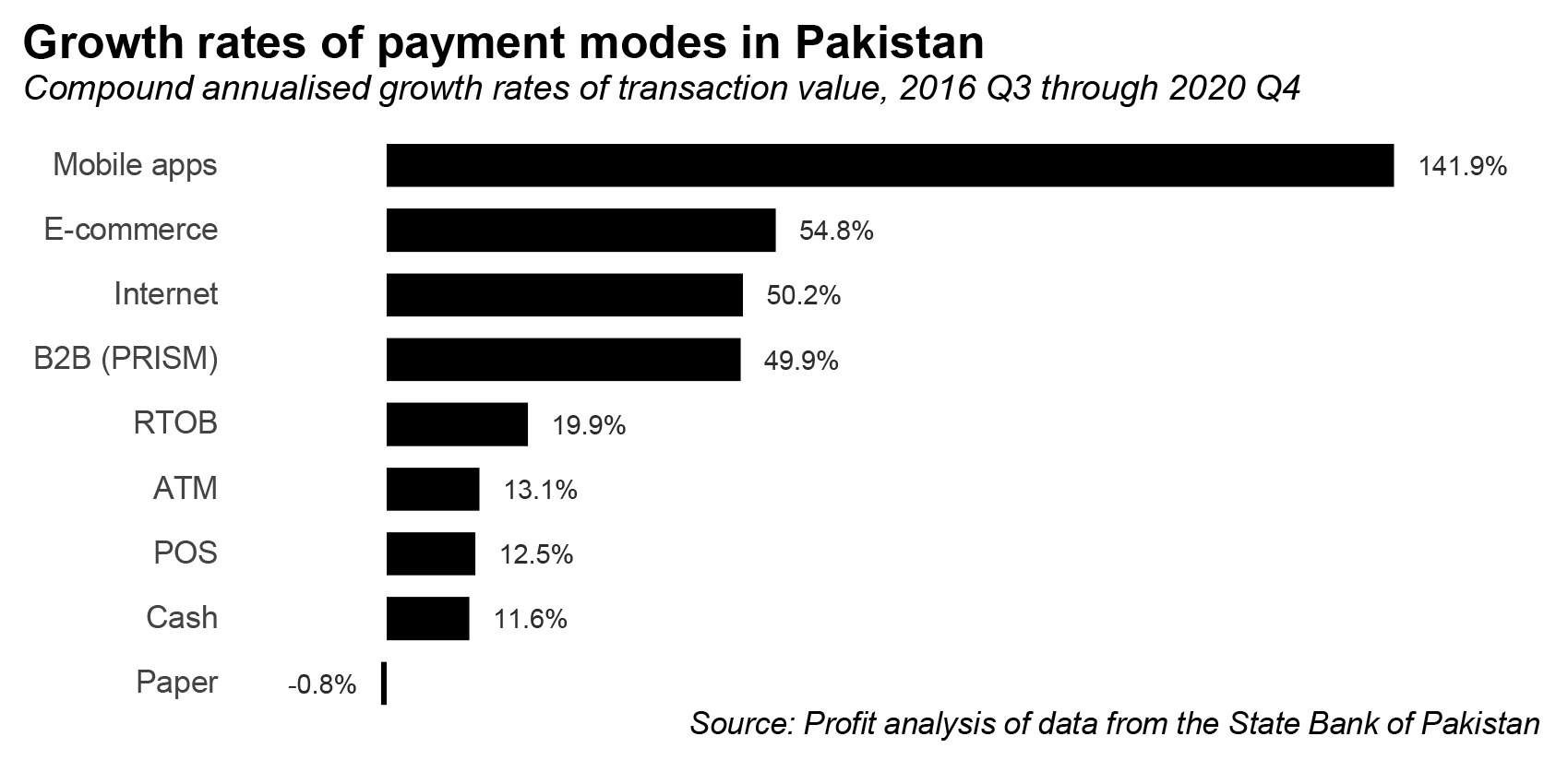

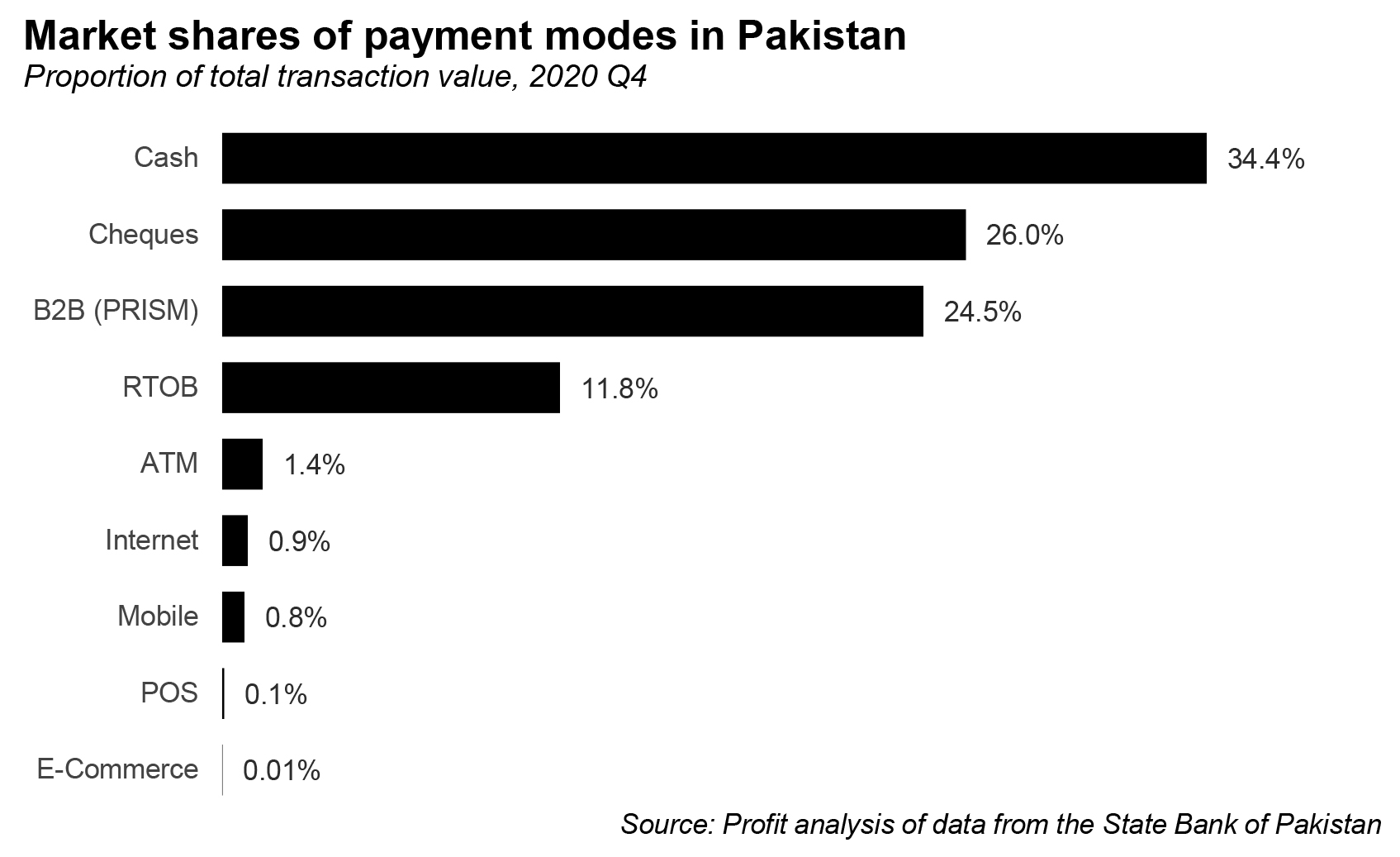

How rapid? Data from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) is unambiguous on this point: strip out the internet-based payments system (bank websites, mobile apps, and e-commerce), and the rest of the country’s payment system (mostly cash, ATMs, and branch banking) has grown at just 6.7% per year on an annualized basis, between the third quarter of 2016 and the fourth quarter of 2020. Inflation during that period, by the way, averaged 7.5% per year, meaning the real purchasing power of the non-internet-based payments system went down during that period.

What happened to the internet-based payments volume during that period? They went up by an annualized average of 70.1% per year. And, when we say internet-based transactions, we mean bank websites, bank and payment provider mobile apps, and credit and debit card transactions on e-commerce websites (excluding cash-on-delivery transactions).

The internet may only account for only about 1.7% of all transactions in Pakistan right now, but there is no question that it is the only form of payments that Pakistanis clearly want to use more of than they are now. Nothing else comes even remotely close.

What that means is that there is significant growth opportunity for fintech startups in the payments space. Using State Bank data, Profit estimates that approximately Rs200 trillion worth of transactions take place entirely in cash each, and a significant portion of the remaining Rs580 trillion worth of transactions also involve at least some level of cash usage. Converting that to electronic means, even if a company only earns mere basis points on each transaction, will be a huge business.

And given the fact that this is the precursor layer for the emergence of a robust fintech sector, it stands to reason payments is the one area that has attracted early attention from venture capital investors. All but one fintech company that managed to raise financing in 2021 has or is pursuing either a Payment Services Provider (PSP) license or an Electronic Money Institution (EMI) license, both of which allow companies to provide payment solutions to retail customers.

Once this layer of fintech is created and functioning, offering financial services to both individuals and businesses can begin. And that is where the complications begin.

Putting the bank in ‘neobank’

It is a neologism in the fintech world that every fintech company claims to not want to be a bank, but wants to become a bank, whether or not they are willing to admit it to themselves.

You can certainly see why this would be the case. Electronic Money Institutions (EMI), for instance, are allowed to not just facilitate money transfers between two parties but also to store money electronically into their user accounts. That sounds a lot like – and functionally, it is – a deposit. Like a bank deposit, that money is available in theory for the EMI to invest for a return. And the EMI can also, in theory, pay out some of those returns to their depositors to encourage more deposits into their system.

What I have described above is technologically possible and functionally the same thing as banking, except that it takes place entirely electronically and does not require a physical branch network to function. The problem is that, under current regulations enforced by the State Bank of Pakistan, most of the banking functions I have described are illegal.

Paying an interest rate to depositors is outright banned for EMIs. No limits, no capital requirements, nothing. Just plain banned. Investing deposits into government bonds (and only government bonds) is allowed, but only 50% of the previous three months’ balance, which does not sound bad until you consider the fact that EMIs have higher capital requirements than banks, but are allowed to invest far less of their deposits than the banks.

Okay, so an EMI cannot use interest to attract deposits, and can only generate limited revenue from investing those deposits, but at least the license theoretically allows one to create a basic payment system that could function as the default financial app for its users if it is able to create a slick enough user interface, right?

Theoretically, sure. In practice, good friggin’ luck.

Here is why: not only are you not allowed to pay interest to depositors, and can earn less revenue than a bank on any deposits you are miraculously able to attract, you also face transaction limits on just how much money people can move into their digital wallets. In any given month, a client cannot move more than Rs50,000 into their digital wallet, unless they complete biometric verification, in which case they will be allowed to move up to Rs200,000 per month into their digital wallet. Cash withdrawals are limited to Rs10,000 per day, regardless of the level of verification of the account.

By contrast, once you have a biometric verification at a traditional bank, the regulator places virtually no limits on the volume of transactions per month.

In short, an EMI is creating a product that competes with basic banking services, but is forced to deliver a product that is functionally inferior in terms of its actual financial services (low transaction limits, no interest on deposits, and no lending) and must rely solely on a narrow subset of customers who are tech-savvy enough to appreciate a slick interface, but poor enough to not need to transact more than Rs10,000 on any given day.

The State Bank has created another two levels of licenses – Digital Retail Bank (DRB) and Digital Full Bank (DFB) that remove many of these restrictions – that EMIs are explicitly allowed to grow into. But growing to that level on an EMI license alone is likely to prove difficult. A DRB is allowed to perform all the services of a regular bank, except that it cannot serve corporate clients. A DFB is allowed to serve all types of clients, but without a physical branch network.

If it is not obvious by now, we will say it explicitly: if the only license a fintech startup holds is issued by the State Bank of Pakistan, it is all but doomed to failure. The regulations will force the company to deliver an inferior product and leave it struggling to achieve the scale it needs to keep attracting the capital it needs to grow.

We want to make one thing very explicit: this is not due to some malice on the part of the State Bank. Indeed, if you ever speak to line officers at the State Bank in charge of regulatory functions, you will find civil servants who know their subject matter well and appear to be quite dedicated to truly helping citizens and businesses.

It is just that the State Bank has several responsibilities and stakeholders and while the most important are depositors, the second-most important ones are the traditional banks. So when a traditional bank comes in to lobby for regulations that claim to be in the interest of keeping the depositors’ money safe, the State Bank is likely to find itself persuaded by such arguments.

Transaction limits, limits on paying interest, and limits on where and how much an EMI can invest its deposits do keep depositor money safe. They just do so at the expense of quality services, and offer greater hindrances than the traditional banks are subject to.

The State Bank, of course, has a reasonable response: if it allowed EMIs to deliver the same services as the banks, it would functionally be removing the minimum capital requirements it has for the banks, where the minimum paid up capital starts at Rs13 billion. If an EMI with a minimum paid up capital of Rs200 million is allowed to do all of the same things as a bank with a much higher minimum paid up capital, that would be unfair to the investors of the banks who were asked to risk a lot more money.

And the State Bank has created a glide path that allows EMIs to grow into banks. It starts off the EMI license at a minimum paid up capital at Rs200 million, allows a Digital Retail Banking license at Rs1.5 billion, and a Digital Full Bank license at a minimum paid up capital of Rs6.5 billion, still well below the Rs13 billion required for a traditional banking license.

Even once you reach the promised land of a Digital Full Banking license, you now find yourself at the mercy of the Prudential Regulations. This is a set of rules that is, in theory, designed to ensure the safety of the banking system, but in practice means that risk management for banks is effectively outsourced to the State Bank itself.

There is much to criticize in the Prudential Regulations, but the one part most directly relevant to fintech startups is this: it regulates all banks as general purpose banks, and does not allow much in the way of specialization. So, for example, if a fintech startup wanted to specialize in becoming the go-to deposit and lending source for the retail sector because its founders had expertise there and wanted to offer the best service to clients in that sector, they would not be allowed to do so by the State Bank under the Prudential Regulations, which stipulate strict limits on exposure to specific sectors, effectively banning specialization.

The specialization ban, by the way, is why the big banks stay big and the small banks stay small, with very little movement in the rankings. No bank – nor any fintech startup – is allowed to achieve high quality of service or economies of scale by focusing its energies on a single sector. By forcing all the banks to compete for the full spectrum of business sectors, the Prudential Regulations give an advantage to the large ones that can afford to have specialists for each sector.

So, if you want to become the neobank that provides services to freelancers, for example, you will find yourself afoul of the regulations and will need to develop a more general product. No bank or fintech startup is allowed niches. Everyone must compete with the Big Five for everything.

Of course, some niches slip through the cracks, which is why Meezan Bank’s Islamic niche has allowed it to become the largest bank in Pakistan by market capitalization and why Oraan, which wants to become a neobank for women, has a good chance of success.

But for most others, it is an uphill battle in a market that is heavily tilted in favour of the incumbents, even with a regulator that has moved significantly in the direction of allowing innovative companies room to operate.

The politics of fintech

So, what can a fintech startup do? Well, the answer to that question starts by understanding who has power in Pakistani finance now, what they value, and then figuring out a way to get what you need from them without expecting them to give up on any of their core interests.

The answers to all of those questions are obvious. This is a bank-centric financial system so it is the big banks that have power, and they value one thing above all else: their complete dominance of deposit-taking ability. If your startup intends to compete with their ability to take deposits, do not expect cooperation from the banks, and do not expect the State Bank to be particularly friendly to your lobbying, because the big banks have better lobbyists than you and can rely on very reasonable-sounding arguments that all purport to be in the interest of protecting the depositor.

If you are small, expecting better technology to drive users to you and away from the banks is going to be hard, if not impossible. Why? Because the banks control the on- and off-ramps to the financial system and have no incentive to cooperate with you. What does that mean? Where will a person’s initial deposit into an EMI wallet come from? Probably a bank account, and the banks can – and do – set arbitrary limits on how much they will allow to be transferred into EMI wallets. Yes, these limits are lower than the ones already written into the State Bank’s EMI regulations. The ability to move money into the EMI wallet is the on-ramp, controlled mostly by the banks.

Then there is the ability to withdraw money, which is the off-ramp. EMIs can and are issuing debit cards that customers can use to withdraw money from ATMs, but the ATMs are run by the banks, and they are unlikely to offer discounts on ATM transactions to the EMIs, meaning an EMI customer will always have to pay ATM fees.

This is best illustrated with an example. My brother has both an HBL account and a SadaPay account and debit cards from both. HBL has 2,157 ATMs where he can withdraw money without paying a fee. SadaPay has zero ATMs, which means he has to pay a Rs18 per transaction fee whenever he wants cash. According to the State Bank, the average ATM withdrawal is Rs3,000, which means the average ATM transaction fee would represent a 0.6% transaction charge.

Right now, my brother does not want to pay that fee, so he puts very little money into his SadaPay account. And it makes no sense for SadaPay to try to absorb the 0.6% transaction fees because it would need to make that amount back in interest on the deposits, which would be very difficult to do. SadaPay would need government bonds to yield 14.4% per year (0.6% multiplied by 12 months and divided by the 50% investment-to-deposit limit) to break even on monthly withdrawals of average size, which is simply not possible.

By comparison, the path of fintech startups that are focused on lending is somewhat easier. Abhi, for example, is focused on salary advances, a market the banks are currently happy to leave unserved, meaning Abhi has the market almost entirely to itself and is unlikely to encounter resistance. And Finja’s small business lending business also does not compete against anything the banks actually want to do. Indeed, the banks are so willing to let fintech startups take that market that Habib Bank Ltd has provided $10 million in debt capital to Finja to fund that small business lending program.

If either Finja or Abhi tried lending to, for example, Engro, they would find resistance from the banks very quickly. Do not touch their corporate clients, and do not try to compete for deposits, and the banks are more than happy to collaborate with you on any business that would involve you paying them either interest or fees of any kind.

That leaves a tremendous amount of the financial services spectrum open. Most non-government lending is wide open to fintech startups, provided they can get around the Prudential Regulations by seeking either waivers or other licensing arrangements. It requires startups to rely on non-deposit funding sources, such as bonds or commercial paper, which is more expensive, but given the ostensibly lower operating costs of tech-first financial services companies, may not be prohibitively so.

So, what will fintech achieve?

The value of Pakistani fintech will be in covering the vast majority of services that the banks currently do not offer and simply have no interest in offering either. That leaves a tremendous amount of economic value open to fintech startups and it is entirely conceivable that there will be not one, but several fintech companies worth more than the banks.

That is not as difficult as one might imagine. The market capitalization of the most valuable bank in Pakistan – Meezan Bank – is just over $1.2 billion. Even as that number will rise over the next decade, it is easy to conceive of more than a few fintech unicorns with their $1 billion+ valuations being higher than those of the mid-tier banks.

Will the fintech knight slay the banking dragon? No, but it also does not need to. In their laziness, the banks have left so much open that there is room to grow without confrontation. The financial services sector in Pakistan will offer more services, with a greater diversity of players, as a result of the rise of fintech players. That is likely to result in profitable growth, with arguably little disruption needed.

A lot of fintechs are in the collection and payment space, however the real question is who will be able to provide a viable financing solution to the different players connected to the ecosystem. I believe the fintech which is able to solve this will take the lead as the product offering is more or less the same for most of the fintechs.

I guess politics mean fintechs can support but not disrupt. There is nothing wrong with working in tandem with incumbents. However the sloth like internal movement in banks defeats the entire premise of a startup trying to deliver its product fast and then move towards iteration. Those who have the capital and patience to aggregate the value of the ecosystem will survive.