For four decades, Pakistan has largely planned with spreadsheets, intuition, and press conferences. What we have not done at least not at scale is simulate policies before launch and then monitor whether promised results actually arrived. We built “monitoring cells” without monitoring systems. The result is short-term firefighting, long-term drift, and a data pipeline that too often fails the very ministries tasked with steering the economy. What I call “press conference economics”.

The price of flying blind

When a tariff is tweaked or a sales tax is nudged by 1%, the shock ripples through prices (CPI), jobs, exports, provincial revenues, and household welfare. Countries that treat the economy as a system run those “what-ifs” through integrated models before acting, we usually don’t. Insiders at planning commission, Ministry of Finance will recognize the culture: ad-hoc “quick looks,” post-hoc justifications, and what one senior official described to me as “jhatka” fixes shocks meant to show action rather than deliver measurable outcomes(a bureaucratic colloquialism not a method).

Meanwhile, the data itself hasn’t helped. The finance minister recently criticized the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) for forcing policy to rely on outdated indicators concerns widely reported in the press. In parallel, the IMF has asked Pakistan to explain roughly $11 billion in trade-data discrepancies between two government systems over the last two fiscal years exactly the kind of problem a governed data fabric would surface and resolve faster. Dr. Aneel Salman’s “The Price of Statistical Silence” underscores the same point: inconsistent systems create large statistical gaps that corrode trust.

The same simulation logic

Our defence institutions have used computer-assisted war games for decades to rehearse decisions under uncertainty. Pakistan’s National War Gaming Centre (NDU) supports war games and operations planning, the U.S. Naval War College has institutionalized wargaming since 1887 and runs 50+ gaming events annually. The method is identical to what economic policy needs. Policymakers need to define objectives, generate scenarios, simulate moves and countermoves, observe outcomes, then update plans based on evidence not gut feel.

If wargaming helps armies avoid costly mistakes before battle, why wouldn’t we wargame our economy before rolling out a tariff, subsidy, or tax reform.

There are plenty of examples that Pakistan can borrow from. To understand how secure data backbones are developed, for example, there is the UK’s Integrated Data Service and New Zealand’s Integrated Data Infrastructure which securely link tax, trade, labour and other datasets for cross-government analysis.

The OECD’s METRO (CGE) traces shocks through sectors and value chains exactly the “import => CPI/jobs/exports” linkage Pakistan needs. Even pedagogy related to this is mature. Business schools like Stanford GSB & MIT use management flight simulators (e.g., MIT Sloan’s Platform Wars) so leaders can practice strategy in complex systems the same mindset we need in public policy.

The stack Pakistan actually needs

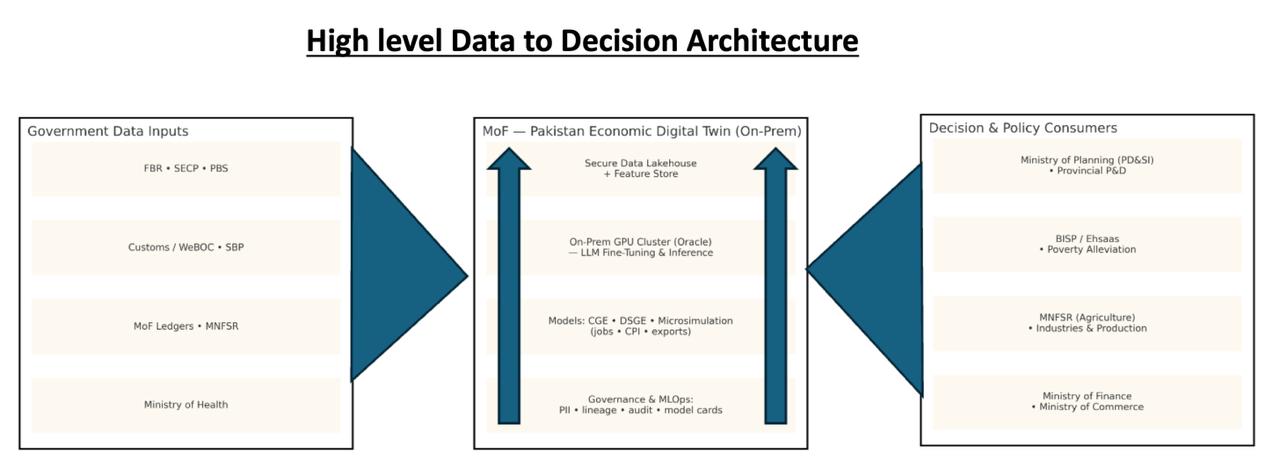

Roughly speaking, Pakistan’s economic planning needs the development of four distinct steps.

- Live data fabric (governed): automated feeds from FBR, Customs/WeBOC, SECP, SBP, PBS, MoF ledgers, Health, MNFSR into a trusted environment with lineage, access controls, and audit. One “economic truth” analysts across ministries can query (and challenge).

- Models at three layers:

o Macro (CGE/DSGE): quantify sector/province impacts of tariffs, subsidies, energy price paths, exchange-rate scenarios.

o Micro (tax-benefit, labour): show distributional effects and improve BISP/Ehsaas targeting.

o LLM + retrieval: assistants that retrieve from governed data (no hallucinations), call the models, and return cited answers in Urdu/English.

- Decision workbench: what-if consoles where MoF, Planning, line ministries and provinces move policy sliders and see CPI, GVA, jobs, exports change before announcements.

- Monitoring & ROI by design: tag every rupee in PSDP/ADP to ex-ante projections and ex-post outcomes, with drift alerts and public scorecards.

The PBS collecting data is not enough

The Pakistan Bureau of Statistics is essential in all of this. But what we must remember is that collection of data does not guarantee data-based decision-making. The real goal should not just be to collect data. Timeliness, validation and integration across agencies are vital. A digital twin forces the hard parts metadata, versioning, reconciliation, and a single source of truth so ministers see one dashboard, not five conflicting spreadsheets.

The frameworks already existed: input-output tables, macroeconometric models, early CGE. Had we institutionalized simulation in the 1980s, we would have learned faster, avoided tariff whiplash, and targeted subsidies with more precision. Instead, we staffed monitoring teams without monitoring systems reporting activities, not ROI. In my Stanford coursework, simulations like Platform Wars highlighted dynamic complexity and how small policy changes compound over time. Pakistan’s policymaking still repeats precisely those errors.

The road ahead

So what comes next? Well, Pakistan’s policymakers can begin by following a pragmatic approach that phases in these changes over a period of a year to a year and a half. These phases could look something like this:

- Phase 1 Data & governance: Connect Customs/WeBOC, FBR, SECP, SBP, PBS, MoF into a secure lakehouse, publish a data dictionary and quality KPIs.

- Phase 2 Models & LLMs: Deploy a baseline CGE calibrated to Pakistan tables i.e. plug in tax-benefit microsim, add an LLM that answers with retrieved, cited facts and can call the models. Computers can be on local, on-prem GPUs and hosted in a shared government-approved facility (e.g., upcoming Sky47 or Jazz Digital Park) to meet residency needs.

- Phase 3 Policy pilots: Run three scenarios (e.g., fertilizer tariff relief, electricity price path, export-rebate redesign) and publish ex-ante vs. ex-post scorecards.

- Phase 4 Institutionalize: Embed model stewardship, code reviews, annual re-calibration, require simulation memos in ECNEC/CDWP/PDWP submissions.

If we keep doing press-conference economics, we’ll keep getting press-conference results. If we build the simulation habit, we’ll finally have a policy with memory and a way to learn from it.