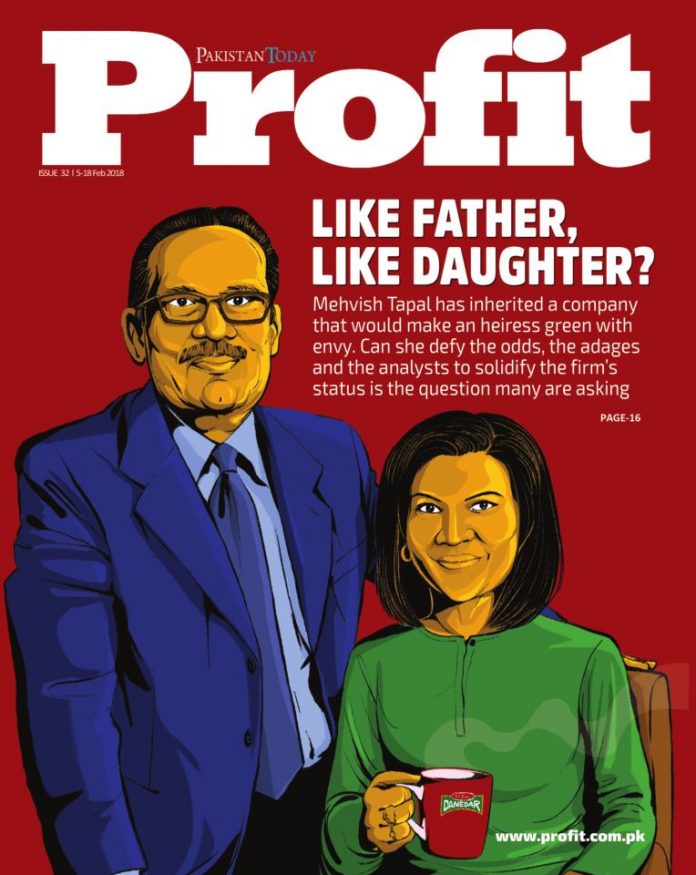

She’s going to be the fourth Tapal to run the tea empire. The odds are against Mehvish Tapal. At least statistically speaking. Studies have shown that mostly it is the third generation of family-run businesses that runs the concern to the ground. Her father was one of the statistical outliers; could she carry on this winning streak?

Any such discussion on a family owned concern leads to a more abstract, general discussion on the dynamics at play.

The primary argument against the Seth-model centres around the lack of accountability.

Things are worse when the next generation, or the one after that, is in charge. They wouldn’t have gone through the scrappy hustle that set the business up in the first place.

The arguments for that relative lack of accountability in Seth-run firms could be a strength as well. When a company is making a fundamental shift in its core businesses, career-employees can be bullied into playing it safe; owners, not so much.

Lastly, when the going gets tough, when the company is forced to sell its good silver, career employees can’t be faulted for leaving. Why would they put their personal lives and financial futures at risk for an endeavour which, even if things do work out, won’t yield them anything? Owners and their kids, on the other hand, can’t just give up and leave. There is a measure of comforting certainty in that, especially for investors evaluating a company to invest in.

In Pakistan, coming back to the tea industry, things haven’t been bad for family-run concerns and have been bad for professionally run firms. While Tapal – and its challenger Vital – have thrived (both are family run), Unilever’s Lipton has lost market share rapidly, despite its immense brand equity and professional management that is typical of multinationals.

The owners choosing their progeny to run their businesses is, demonstrably, not necessarily a bad idea. But only if the children are up to the task. As a father myself, I know how difficult it is to evaluate one’s own children, but it is an evaluation that nevertheless needs to be done. Perhaps an audit from the outside would help.

Many factors need to be taken into account. Does the child actually want to be in the business? Are they up to the task intellectually? And, given how they have had a plush existence, not knowing the struggle that their fathers did, do they have the requisite passion?

At the end of the day, even for privately held businesses, there should be a separation between the business and the person who owns it. If the sole purpose of the business is to earn money for the owner and nothing else, then perhaps treating it as an asset, a dukaan, so to speak, to pass on to the next generation makes sense. But if the idea is to treat a corporation as a rich, pulsating organism unto itself, then there is a need to modify the instinctive impulse to pass on the reins to one’s children and see who would be actually a good fit for the job, family member or not.

Babar Nizami

Managing Editor

Salaams.

A very well researched and thoughtful insight into the tea business and the family run business success at its peak!!

A company like Tapal Tea needs a full time, with long experienced HR external director to undertake SWOT analysis and lead a succession program.

Brilliantly done.

Similarly the Steel industry needs good R&D to undertake SWOT analysis of the products it is producing.

In the market Deformed bars made as per ASTM grade 60 standards have questionable quality. Mr Abbas may like to comment.

Comments are closed.