In 1969, the administration of President Ayub Khan had been growing unpopular for many reasons, but the triggering event that brought more than just committed student activists to the streets was a rise in the price of wheat. Ten years of industrial progress was forgotten in an instant because of the price of bread.

In 2007, Pervez Musharraf was presiding over what, until then, had been the largest expansion of Pakistan’s middle class, but when the price of fuel rose too fast for the government to be able to control through subsidies, the lawyers and students who had been agitating for the rule of law were joined by ordinary voters, and out went Pakistan’s last enlightened despot.

In each of those cases – and many others throughout history – economics was not what made those regimes brittle in the first place. Authoritarian and despotic regimes of any kind often contain within them the ingredients for their own demise. But it is almost always bread and butter issues that infuse the courage in the common man to join the intellectual agitator in delivering the death blow to those regimes.

“It’s the economy, stupid,” in short, does not begin to describe the consequences of a nation’s economic conditions on its political future.

In democratic dispensations, however, the direction of causality is more often reversed: political choices made by voters end up having a significant effect on the economic fate of the republic. With that in mind, we at Profit have set out to determine – as best as we can, given the lack of developed policy debate in Pakistan – what choices face the voters in the 2018 elections.

This is, after all, the primary justification of the freedom of the press: to hold the powerful to account, and to inform the voters about the actions of their government, and the choices they face in the ballot box. We feel so strongly that this is our duty that we have dedicated the entirety of this issue to discussing the various issues – at least the ones most directly tied to the economy – that voters must decide upon.

Format of the issue

The format of this issue, then, is different from our normal ones. In our cover story, we examine the broad highlights of the economic progress made by the country over the past five years, and take a look at two of the key policy priorities – taxation and civil service reform – that we believe will overshadow all others. Each of the subsequent stories will have three sections:

* The facts on the ground: where Pakistan is, and how it got here;

* The agreed approaches: the areas of agreement between the major national political parties;

* The debate: where the major national political parties disagree, what each party believes, and why.

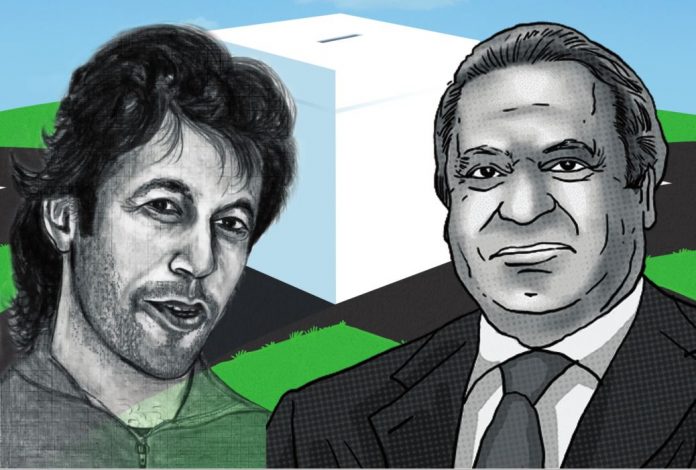

For the purposes of this issue, we have restricted ourselves to the positions held by the country’s two largest political parties – the outgoing Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) and the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI). We address the third major political party – the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) – in a separate article, where we examine the ideological divisions within the party. Our reason for focusing on the PML-N and the PTI: the two are by far the likeliest contenders for the Prime Minister’s Office, and the PPP has all but given up on the idea of governance or ideology for the most part.

We have also excluded smaller political parties under the assumption that they are likely to join a coalition with one of the two major parties which will then drive the national agenda, or they will sit on the opposition benches in Parliament, in which case their direct impact on national economic policymaking is likely to be limited for the next five years.

For the facts on the ground, we rely mostly on data from a variety of sources, including the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, the State Bank of Pakistan, the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority, the Federal Finance Ministry, and the World Bank. We recognise that the selection of which facts to include – and how they are presented – in itself relies on a degree of editorial judgement, though we have attempted as far as possible to stay neutral in our statement of the facts themselves.

With respect to the agreed approaches, we wished to highlight any areas where the two major parties agree. Since both parties are – at least nominally – right-of-center political parties, this is not an insignificant area of discussion.

As for the debate, we have relied upon direct interviews with party leaders, public statements, and publicly available manifesto documents put out by each political party to discern their respective stances on each of the main issues we discuss. The arguments laid out here will represent – to the degree possible – the best form of each party’s case, and will be presented in the form of a WhatsApp conversation between two hypothetical party leaders.

Why use the ‘best form’ of the argument

We understand that voters in Pakistan are – correctly – cynical about the abilities or sincerity of any political party in implementing an agenda that improves the lives of the citizens of this country. We leave assessments of levels of corruption, incompetence, and naivete to each individual reader. Our goal is to examine the proposals and policy differences between the two major political parties as they intend them to be and not apply any further assessment about relative effectiveness to it.

Our reasoning: to do so would necessarily introduce a level of political bias into this analysis that would render such an exercise into a piece of propaganda for one party or another. In order to remain neutral, we make a ‘good faith’ assessment of each political party’s agenda: what would it look like if the best effort was made to implement it, and how does it compare to its rival.

We do this also, in part, to offer Pakistan an alternative to ‘youthia versus patwari’ trolling that typically takes place on social media, most vociferously on Twitter, but also on Facebook. We believe our nascent republic deserves an elevated debate of policy and political principles, and that part of the job of the fourth estate is to hold politicians to a higher standard.

Why taxes and civil service reform top our list of issues

Regardless of what any individual voter believes the government should or should not be doing, it is undeniable that the government will need both money and competent and properly incentivised civil servants to get anything done.

The government of Pakistan, since the very founding of the country, has not been able to pay for itself (your grandparents who tell you otherwise are lying). That inability to pay for our own expenses has resulted in a massive buildup of debt, and made policymaking in the country the preserve of foreign donor-funded consultants, rather than politicians and civil servants paid by the citizens and taxpayers of Pakistan.

There is also, by now, a consensus that the Civil Service of Pakistan, at least in its current manifestation, is not a functional institution and needs serious reform in order to become more effective in formulating and implementing policies, as well as becoming a more mindful custodian of public money (translation: they are largely corrupt and incompetent). Most independent analysts who study the issue agree that the Civil Service has become more interested in preserving and advancing its own privileges rather than the interests of the citizens it was created to serve.

Representation without taxation

In December 1773, as American revolutionaries dumped tea shipments from the British East India Company into the Boston harbour, they were revolting against the idea of “taxation without representation”, that they were taxed by the British government without having representatives in Parliament to help determine how their tax money would be spent. The link between taxation and accountability of government is at least as old as the Magna Carta, which dates back to 1215, when the English aristocracy and urban middle class forced King John to accept constraints on his power, through Parliament, if he were to retain his right to tax his subjects.

In Pakistan, however, we have always gotten this balance wrong. From the very early days following Partition, the government of Pakistan has failed to adequately tax its people, particularly its wealthy elite, and relied instead on aid from foreign powers, largely the United States, but also Britain and Japan and now China, in order to pay for the cost of running the country.

Perhaps this aversion can be attributed to the fact that Pakistan’s creation owes in large part to the defection of Muslim political leaders from the Congress-allied Unionist Party, a defection that decisively turned political opinion in what is now Pakistani Punjab towards being in favour of Partition and the creation of Pakistan. That political leadership consisted largely of rural landed aristocrats and urban industrialists, who joined forces with their Muslim counterparts who migrated from the United Provinces of Agra and Awadh to form a government in Pakistan that systematically served its elite without burdening them with taxes.

That fateful choice at Partition lasts until this very day. The Pakistani wealthy elite do not believe the government should tax them, and do not even bother to convincingly hide their tax evasion. And yet, the entire structure of government is bent towards serving them.

On the taxation side, the urban industrial elite get tax credits and exemptions for their export-oriented manufacturing units (which many claim even on non-export-oriented production), in addition to concessional prices on inputs such as electricity and natural gas. And the rural landed elite is virtually exempted from any taxation altogether. (In theory, provincial governments levy taxes on agricultural income, but the taxes are so miniscule, and so rarely ever collected, that the rural aristocracy is virtually untaxed on its income.)

And all of this is before we even get into the problem of tax evasion, which pervades virtually all segments of the economy, barring the few that are documented by their very nature (banks, telecommunications), or controlled by the government or large multinational corporations (energy, tobacco). Well over half of all taxation (54% in 2013) is collected at Karachi Port and Port Qasim, where the government can literally hold an importer’s goods to ransom until they pay their taxes (which includes sales tax, customs duties, and income taxes in the form of a withholding tax).

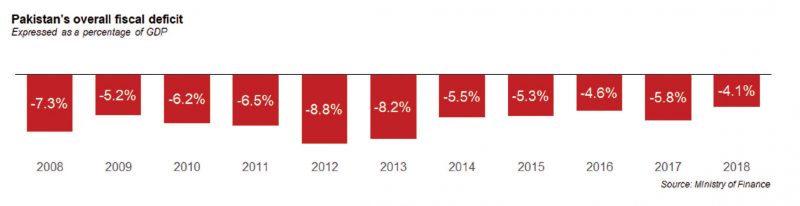

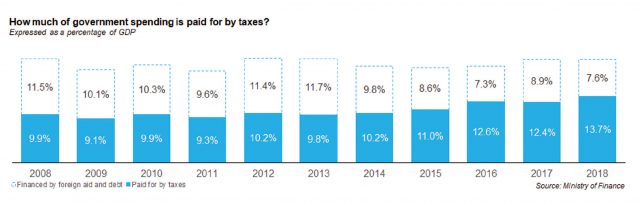

Profit examined Pakistan’s budget deficit data as far back as we could get reliable numbers for, and we found no surpluses ever since at least 1986 (and we suspect much further in history than that). And budget deficits lower than 2% of the total size of the economy have not been seen since the early 1990s. More recent years have numbers hovering between 4% and 6% of gross domestic product (GDP) with some years going as high as 8.8% of GDP.

And by the way, these numbers charitably include foreign aid as ‘government revenue’. If one expands the definition of fiscal deficit to include total government spending minus total tax revenues alone, the budget deficit routinely runs into 10% of GDP in the good years, and 12-13% in the bad years.

Quite simply, the government collects between 9% and 12% of the GDP in a given year in taxes, and spends very consistently between 19% and 21% of GDP on all services as well as its own financing costs. In short, half of Pakistan’s needs from its government are paid for by foreign governments and borrowing from both domestic and foreign lenders. And increasingly, the balance of that second half is shifting towards borrowing, as more and more governments and voters in other countries ask themselves: “Why should we continue to pay for Pakistan when its own wealthy elite refuse to do so?”

Tax reform proposals

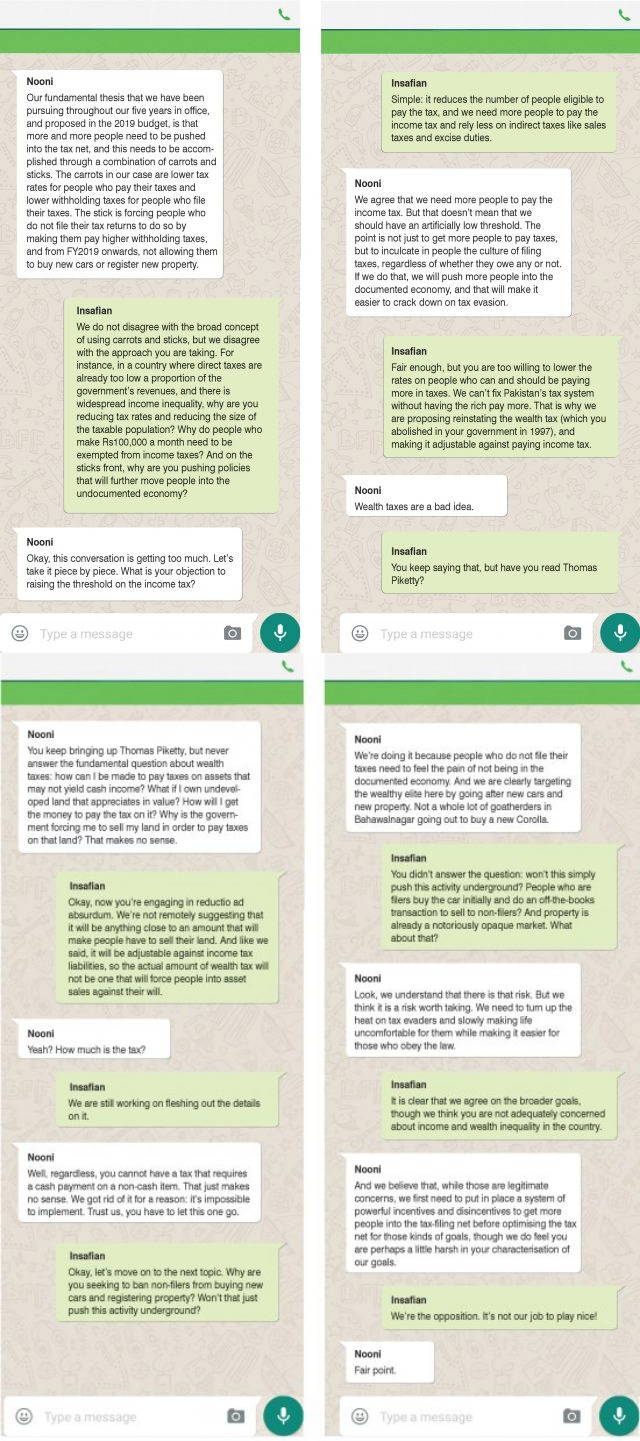

A simulated conversation between the PML-N and the PTI on the matter of taxation

This is an area where there are relatively few concrete proposals from either side of the political spectrum, though the PML-N can be said to have announced its intentions in the federal budget for fiscal year 2019. What follows is a simulated conversation between the PML-N and the PTI on the matter of taxation.

PML-N: Our fundamental thesis that we have been pursuing throughout our five years in office, and proposed in the 2019 budget, is that more and more people need to be pushed into the tax net, and this needs to be accomplished through a combination of carrots and sticks. The carrots in our case are lower tax rates for people who pay their taxes and lower withholding taxes for people who file their taxes. The stick is forcing people who do not file their tax returns to do so by making them pay higher withholding taxes, and from FY2019 onwards, not allowing them to buy new cars or register new property.

PTI: We do not disagree with the broad concept of using carrots and sticks, but we disagree with the approach you are taking. For instance, in a country where direct taxes are already too low a proportion of the government’s revenues, and there is widespread income inequality, why are you reducing tax rates and reducing the size of the taxable population? Why do people who make Rs100,000 a month need to be exempted from income taxes? And on the sticks front, why are you pushing policies that will further move people into the undocumented economy?

PML-N: Okay, this conversation is getting too much. Let’s take it piece by piece. What is your objection to raising the threshold on the income tax?

PTI: Simple: it reduces the number of people eligible to pay the tax, and we need more people to pay the income tax and rely less on indirect taxes like sales taxes and excise duties.

PML-N: We agree that we need more people to pay the income tax. But that doesn’t mean that we should have an artificially low threshold. The point is not just to get more people to pay taxes, but to inculcate in people the culture of filing taxes, regardless of whether they owe any or not. If we do that, we will push more people into the documented economy, and that will make it easier to crack down on tax evasion.

PTI: Fair enough, but you are too willing to lower the rates on people who can and should be paying more in taxes. We can’t fix Pakistan’s tax system without having the rich pay more. That is why we are proposing reinstating the wealth tax (which you abolished in your government in 1997), and making it adjustable against paying income tax.

PML-N: Wealth taxes are a bad idea.

PTI: You keep saying that, but have you read Thomas Piketty?

PML-N: You keep bringing up Thomas Piketty, but never answer the fundamental question about wealth taxes: how can I be made to pay taxes on assets that may not yield cash income? What if I own undeveloped land that appreciates in value? How will I get the money to pay the tax on it? Why is the government forcing me to sell my land in order to pay taxes on that land? That makes no sense.

PTI: Okay, now you’re engaging in reductio ad absurdum. We’re not remotely suggesting that it will be anything close to an amount that will make people have to sell their land. And like we said, it will be adjustable against income tax liabilities, so the actual amount of wealth tax will not be one that will force people into asset sales against their will.

PML-N: Yeah? How much is the tax?

PTI: We are still working on fleshing out the details on it.

PML-N: Well, regardless, you cannot have a tax that requires a cash payment on a non-cash item. That just makes no sense. We got rid of it for a reason: it’s impossible to implement. Trust us, you have to let this one go.

PTI: Okay, let’s move on to the next topic. Why are you seeking to ban non-filers from buying new cars and registering property? Won’t that just push this activity underground?

PML-N: We’re doing it because people who do not file their taxes need to feel the pain of not being in the documented economy. And we are clearly targeting the wealthy elite here by going after new cars and new property. Not a whole lot of goatherders in Bahawalnagar going out to buy a new Corolla.

PTI: You didn’t answer the question: won’t this simply push this activity underground? People who are filers buy the car initially and do an off-the-books transaction to sell to non-filers? And property is already a notoriously opaque market. What about that?

PML-N: Look, we understand that there is that risk. But we think it is a risk worth taking. We need to turn up the heat on tax evaders and slowly making life uncomfortable for them while making it easier for those who obey the law.

PTI: It is clear that we agree on the broader goals, though we think you are not adequately concerned about income and wealth inequality in the country.

PML-N: And we believe that, while those are legitimate concerns, we first need to put in place a system of powerful incentives and disincentives to get more people into the tax-filing net before optimising the tax net for those kinds of goals, though we do feel you are perhaps a little harsh in your characterisation of our goals.

PTI: We’re the opposition. It’s not our job to play nice!

PML-N: Fair point.

Shaking up the civil service

‘A 19th century government serving the needs of a nation in the 21st century’

“We effectively have a 19th century government serving the needs of a nation in the 21st century,” said Nadeemul Haq, former head of the Planning Commission.

At some level, both major political parties recognize this. “Unless you fix that implementation machinery, there is no policy change that will result in improvement,” said Asad Umar, a PTI member of the National Assembly from Islamabad, and most likely designee to be federal finance minister in a possible PTI government.

And Ahsan Iqbal, the PML-N member of the National Assembly from Narowal and outgoing federal planning minister, spent the first half of his time in the cabinet trying to push through an ambitious civil service reform agenda that ultimately ended up getting nowhere.

It is that lack of success on the part of the PML-N that has made the PTI somewhat more wary of trying to push through any such reforms of their own should they come into office in the elections in next month.

“Civil service reform is high on our agenda, but that one is long-term,” said Taimur Khan Jhagra, the ex-McKinsey & Company management consultant who now leads the PTI’s policy unit. “We cannot wait for civil service reform to happen to begin working on the rest of our agenda.”

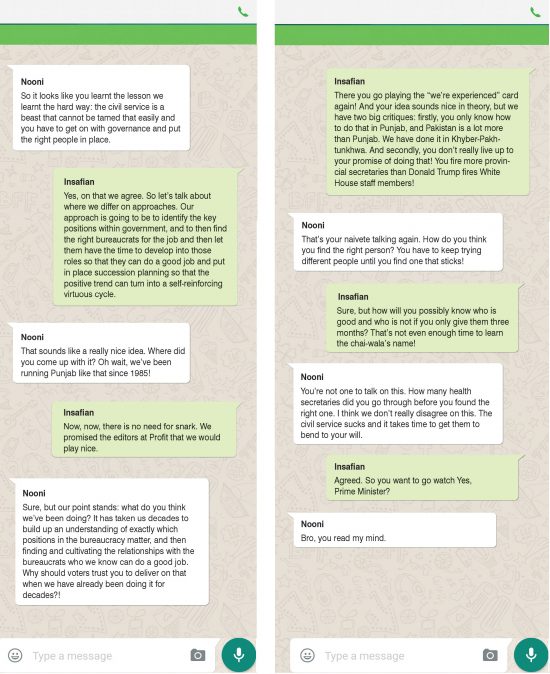

PML-N: So it looks like you learnt the lesson we learnt the hard way: the civil service is a beast that cannot be tamed that easily and you have to get on with governance and put the right people in place.

PTI: Yes, on that we agree. So let’s talk about where we differ on approaches. Our approach is going to be to identify the key positions within government, and to then find the right bureaucrats for the job and then let them have the time to develop into those roles so that they can do a good job and put in place succession planning so that the positive trend can turn into a self-reinforcing virtuous cycle.

PML-N: That sounds like a really nice idea. Where did you come up with it? Oh wait, we’ve been running Punjab like that since 1985!

PTI: Now, now, there is no need for snark. We promised the editors at Profit that we would play nice.

PML-N: Sure, but our point stands: what do you think we’ve been doing? It has taken us decades to build up an understanding of exactly which positions in the bureaucracy matter, and then finding and cultivating the relationships with the bureaucrats who we know can do a good job. Why should voters trust you to deliver on that when we have already been doing it for decades?!

PTI: There you go playing the “we’re experienced” card again! And your idea sounds nice in theory, but we have two big critiques: firstly, you only know how to do that in Punjab, and Pakistan is a lot more than Punjab. We have done it in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. And secondly, you don’t really live up to your promise of doing that! You fire more provincial secretaries than Donald Trump fires White House staff members!

PML-N: That’s your naivete talking again. How do you think you find the right person? You have to keep trying different people until you find one that sticks!

PTI: Sure, but how will you possibly know who is good and who is not if you only give them three months? That’s not even enough time to learn the chai-wala’s name!

PML-N: You’re not one to talk on this. How many health secretaries did you go through before you found the right one. I think we don’t really disagree on this. The civil service sucks and it takes time to get them to bend to your will.

PTI: Agreed. So you want to go watch Yes, Prime Minister?

PML-N: Bro, you read my mind.

A commendable effort, beyond any doubt, at least this can qualify to be called a political debate on economy. I fail to understand why masses are more interested in devouring over petty squabbling of political figures over non significant issues on TV channels and social media spaces. This is the material debate and I wish such debates happens on Live broadcasts by political leaders of opposing sides to lure there voters.

But, pessimisism sorrounds me, Reham’s book or unverified allegation over Sharif’s corruption, issues alike can only get the attention of the masses (educated) of Pakistan.