In 1989, a young man from Karachi by the name of Shahzad Saleem found himself far away from his home city of Karachi, graduating from a strange new MBA programme somewhere in Lahore. A member of only the second batch of MBAs to graduate from the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) MBA programme, Shahzad Saleem left his education in Lahore with his name on the new university’s Dean’s Honour List, and a burning desire to break out into the world of Pakistani business.

In 1990, Saleem laid the foundation of Nishat Chunian Limited as a spinning factory. The company was listed on the stock exchange in the same year. From this humble beginning of a single factory, Nishat Chunian worked its way up to composite textile empire with one of the largest slices of Pakistan’s textile sector. Today, Shahzad Saleem serves as the chief executive of two publicly listed companies. The first of these is Nishat Chunian Limited (NCL), his flagship textile company operating in the home textile, spinning and weaving businesses, which is the 3rd largest textile company in Pakistan by sales revenue. The other is Nishat Chunian Power Limited (NCPL), a 200MW Independent Power Producer (IPP) selling electricity to the national grid.

A Karachi boy born and raised, Saleem got all of his early education from Karachi institutes such as the PAF Model School and the D.J. Science College before graduating with a B.Com degree from the City’s Government Commerce College in 1987. It was only after this that he packed his bags and took the long road to Lahore, joining the second batch of the LUMS MBA, completing the qualification at the age of 22.

“For the longest time I had the record for being the youngest LUMS graduate for a long time. Youngest MBA graduate from LUMS that is,” Shahzad tells Profit, a shy sense of pride still gleaning through all these years and achievements later.

But there was little time to relax or take advantage of this early graduation. Right of the bat Shahzad was on the move, entering the textile business in 1990 by setting up a spinning mill, following this up with a weaving factory set less than a decade later in 1998, and eventually another spinning mill in 2000. “In 2005, we entered home textiles business. During this entire period, we kept on increasing our spinning and weaving capacity as well.”

But why textiles? According to Shahzad, the decision was a no-brainer for him, and he was duty bound to follow in the footsteps of his famous uncle Mian Muhammad Mansha.

“When you’re 22 years old, you don’t think strategy. You choose what you get, and textiles was a family business, my uncle was involved in it and he became instrumental in helping me.”

It would only be in 2010 that Saleem would move away from textiles, establishing an IPP under the banner of Nishat Chunian Power.

“We primarily have three businesses in textiles, and our fourth venture is the power company.”

And while navigating Pakistan’s power sector has been its own journey with its own twists and lessons, the more familiar textile business has had its fair share of troubles.

Peculiar Challenges

Once a prized industry, Shahzad takes us back more than a decade to mark where the downward spiral for textiles in Pakistan began. After the 2008 bombings that rocked Islamabad’s five-star Marriott, foreign companies became reluctant coming to Pakistan. Within the next decade, even as the terror situation worsened and then eventually improved, Pakistan became a no-go are. Foreign companies they had been doing business with for years were no longer ready to come to Pakistan.

“Foreigners are reluctant to come into Pakistan. The reluctance has decreased a little now but there was a time, from 2008 when there was Marriott bombing for almost 7 years, no foreign buyers were coming to Pakistan. Even companies we had regular business with were reluctant to come here. The results were that we had to go everywhere, but Pakistanis don’t get visas easily,” he said, as he delved into the challenges faced by Pakistan’s textile industry.

“Secondly, our policies are not consistent for increasing exports. There are issues of exchange rates, labour policies and government refunds. For the industry to grow it is important that there is some consistency in policy and businesses are treated fairly,” says Shahzad.

Another misnomer, Shahzad decoded, is that the Pakistani textile industry is less competitive than other textile exporting giants in the region such as India and Bangladesh. He rationalized his assertion by explaining that Bangladesh is a converter of imports into exports and pointed out that to look at Bangladesh’s exports, it is important to look at their imports, which are quite large. “There is a huge import of raw materials to Bangladesh which they convert and export. However, in Pakistan, whatever we are exporting, from yarn to the end product, roughly 90 per cent is made here in Pakistan. So it is like comparing apples with oranges.”

“Secondly they had a huge advantage that they got duty free access to Europe long before we did and they were able to build customers much before us,” he says.

Compared to Bangladesh or even India, a disadvantage that the Pakistani textile industry has is the lack of government support and inconsistent policies. Shahzad feels that businesses suffer from an image issue in Pakistan, that the general perception is that businesses do not pay their taxes. “The reputation of businesses here is so bad, that even when businesses have legitimate concerns, it is looked upon by the government with doubt. In India if a businessman is successful, he would be considered a hero. But in Pakistan, first you have to prove that you are not a thief. This just raises the risk of business and hence it demands a higher return. If we want to grow the industrial base of this country, we need to go back to the drawing and rethink the entire policy of dealing with businesses. It’s not about this government or the previous, it goes back much longer.”

He says that though Pakistani textile industry is highly competitive, it is discouraged by an unfavourable cost structure, unlike in India or Bangladesh.

This, however, is contrary to the prevailing sentiment in the country that the textile industry is highly subsidized, but inefficient. Successive governments have tried to accommodate the textile industry by providing them subsidies, sometimes even at the cost of other industries, because of their exports contribution to the Pakistani economy.

Shahzad, however, believes that the concept of textiles receiving subsidies is an alternate reality and the cost structures are very high in Pakistan. “Textile Industry as a whole cannot be discussed as one industry as dynamics of each sector are different. There is a spinning business, there is a weaving business, there is home textile business and there is apparel business in this industry. If we talk about the spinning business, the government says that we need to support local cotton industry which does not grow enough for the requirement of the industry. Yet import is always discourages through different means which effectively means a tax on spinning even before you make any money. Apart from that, the government does not offer any rebate to the spinning industry. Recently, they reduced the cost of energy, that too the cost is half in Sindh compared to Punjab. While a majority of the industry is in Punjab. So if you are going to keep gas prices at half in Sindh and double in Punjab, how is Punjab’s industry going to be competitive?”

“Secondly, there is a large amount of money in the form of sales and income tax refunds that are also being funded by the companies. So this concept of subsidy is a misnomer” he says.

In his opinion, Pakistan’s textile industry does not have efficiency issues. “There are efficient and inefficient industrial units in the textile sector, just like any other industry. But to grow the industry, we need other things as well. You cannot just rely on good efficiency,” he says.

Shahzad argues that the recent increase in minimum wage by the government is also going to increase the cost of production and will hurt the labour class more in the long run because companies will start thinking of automation, which has increased recently. “We should let market forces work so that wage determines its place on its own. It is better that people get ‘x’ salary then get no salary. We need to take steps to increase the size of our economy so that wages go up because of demand supply mechanisms and not government policy,” he argues.

Rupee depreciation and exports

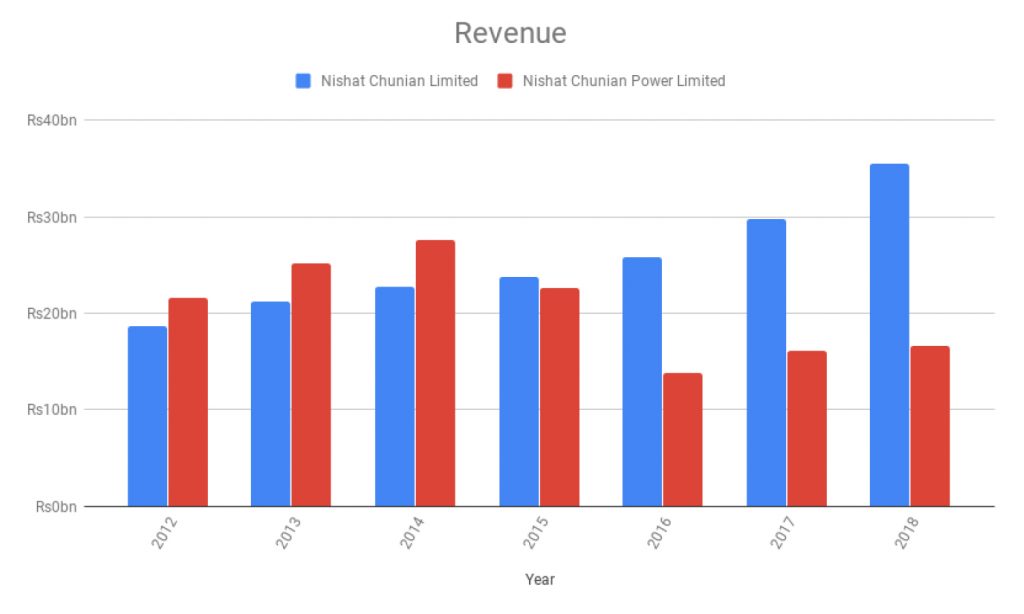

Nishat Chunian Limited is counted among the top textile companies in the country and reported revenue of Rs35.56 billion for the year 2018 and reported profit after taxation of Rs2.36 billion for the same year. In contrast, the revenue for the year 2017 was reported to be Rs29.81 billion and profit after taxation of Rs1.63 billion for the same year.

For the nine months ended on March 31, 2019, the company has reported revenue of Rs29.25 billion against Rs25.74 billion reported for the nine months of 2018 — an increase of 13.64% in the current year.

Majority of Nishat Chunian Limited’s produce is exported, and as Shahzad Saleem tells us, direct exports are roughly 55% of the company’s total sales, and including the indirect exports through other exporters, the total exports form about 80% of the total production. Since the rupee has been constantly losing its value against the dollar, the de-facto currency used in trade, ever since the new government took office, for export-oriented businesses such as Nishat Chunian Limited

this is a blessing in disguise in tough economic conditions, and swells the receivables in rupee terms and gives these companies windfall profits.

Shahzad, however, says that rupee depreciation can give only temporary gains but in the long run, it does not have a long-term advantage because cost increases and some customers also renegotiate.

Rupee devaluation has other cost pressures as well in the form of increased labour costs, increased cost of locally sourced material and high fuel prices also increase. So the temporary gains might possibly get fizzled out in the long run.

Shahzad says that the right level of currency needs to be there and the mechanism defining it is very simple. “It is the 101 of Finance. The difference of interest rate in Pakistan and the dollar should be the minimum depreciation in our currency. So if the interest rate in US dollars is 2.5% and our KIBOR is at 12%, this 9.5% per cent differential has to come from devaluation. Historically, the differential has stayed at 7-8% and that is what devaluation has been. When we don’t devalue for 4-5 years, then we see big devaluations when they are done.”

“If our results are a little better this year, it is because our marketing was a little better, our product was better. Then we have strategic relations with our customers abroad. The impact of these things is more this year. This has a momentum of its own. Especially of export-related industries. Government policy hasn’t changed much. If you talk about Nishat Chunian Limited, we don’t even take electricity from the govt, we have our internal coal-based generation so we don’t benefit from a decrease in gas rates either. In fact we have a large amount of money receivable from the government in sales tax and income tax refund, so the cost of that has actually added up. And it is becoming prohibitive because interest rates have increased so much that its opportunity cost has increased,” Shahzad says.

High-risk, high-returns

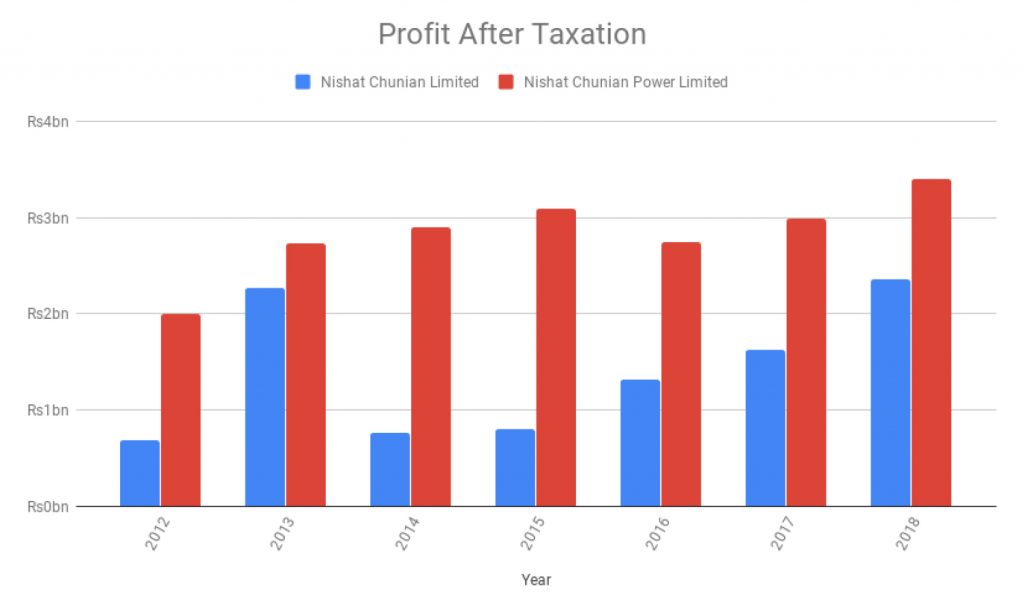

In contrast to the textile business, Nishat Chunian Power Limited, the 200MW furnace oil based IPP which started operations in 2010 and sells electricity to the national grid, earns more profits than Nishat Chunian Limited.

For 2018, NCPL reported revenue of Rs16.59 billion against Rs35.56 billion reported for NCL for the same year. The IPP reported profit after tax of Rs3.4 billion for 2018, compared to profit after tax of Rs2.36 billion reported by NCL in the same year. “IPP profits are not comparable to normal companies. For example the principal repayments are made to IPPs in the first 10 years and are treated as revenue of those 10 years while depreciation is spread over 25 years which obviously results in an overstatement of profits in the first 10 years of all IPP’s. Similarly all costs given to IPP’s are the same over the 25 years while actual costs are less in the earlier years. This also results in an overstatement of profits in the earlier years,” claims Shahzad.

Currently, Nishat Chunian Power Limited among other IPPs is nominated in a NAB inquiry for selling electricity to Central Power Purchasing Authority (CPPA) at exorbitant rates in connivance with National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA), which was being paid for by the consumers.

Shahzad says that NAB has only asked for certain information from them and they will provide more information they ask for. He, however, refused to comment specifically about the case due to its sensitive nature, but regretted that only NCPL was being highlighted by the media while there were other IPPs as well that NAB approached for information.

“NAB has asked questions from many IPPs including us and we are cooperating with them. I have heard that around 50 IPPs have been asked some questions by NAB. However I cannot say with certainty how many IPPs have been asked for information. Certain media houses are spreading rumors about Nishat Chunian Power and we are evaluating our legal options against them,” he says.

Shahzad says that operating in the power sector is difficult because this sector has a bad reputation, and due to the problems faced by companies in the power sector, the risks are higher and, therefore, nobody wants to invest unless they can get a higher return.

“What is really important to realize is that when you increase the risk in any sector, you have to give greater rewards as well. The investors of 1994 in this sector did not come back in 2002. The investors of the 2002 policy did not come back in this round. Because this sector has a bad reputation. Successive governments do not realize this. Today, the return we are giving to the Chinese on power plants, we did not give that to Pakistanis or others. Earlier, people were keen, now they are afraid. Chinese think that there is state protection so they are more willing to invest,” he says.

Shahzad says that the problem in our country is that we are unable to decide how should we make this country prosperous.

“There can be 2-3 ways of being prosperous. If you allege that private sector makes a lot of money and they are not good people, then you can set up textiles and power plants in the public sector and nobody will have a problem. But when we have tried these things in the public sector, the results were very bad. You can compare the results of government run power plants and the private sector. So if we are unable to run these things in the public sector and we eventually have to go to the private sector, it should be understandable that they will earn profits,” he says.

“Look at what happened to Nandipur project. If Nandipur IPP had been set up in the private sector, it would have paid penalty on each day it got late. The government delayed it for years and caused losses of billions. At the end of the day, the public is going to pay for it,” he says.

Shahzad argues that the government needs to decrease risk for the people. “If you are able to get sales-tax refund, income tax refund online, you don’t have to get involved with a government institution, it will save your time and you’ll set up more factories because you will consider it a good business now. But if there are so many problems, it will become difficult and you will ask for greater returns. So it is a simple risk-reward mechanism,” he says.

The simple way for the economy to prosper, says Shahzad, is by decreasing the risk in the economy. “If the risk is going to decrease, reward is going to decrease as well and the cost for the people will also come down. Today, we have increased the risk so much, the reward on it has also increased but who is paying for it? The Pakistani population. Perception is greater than reality. With good intention, you need to have good perception also. That is when the risk will come down in the economy.”

Plans Ahead

The Group plans on reinforcing its presence in the textile sector ahead and move towards value-added segments of the business.

“We like textiles. We want to move towards value added business. We are considering modernisation, improvements, small investments in the textiles sector,” he disclosed.

“We are also planning on going into the real-estate, we are planning to construct a very high-end office building in the Gulberg area. For large investment, we will wait for some clarity in the economic situation. We will make our strategy on that basis,” he added.

NCL under umbrella of Mian Mansha did a good job and earned rewards from MNS during there era of govt.Now they should be focusing on service to the country otherwise Chinese will dominate as they are already doing it in BRI CPEC.

Jaffar Bhai, please refrain from making comments without any proof. What rewards?

very good read

Comments are closed.