The temperature in Lahore has not dropped below 30°C yet, but the ugly grey sheets of smog that the city’s inhabitants have become accustomed to have once again descended in all their overwhelming gloominess. There was a time not too long ago that the winter months were the pride of Lahore. In the course of the past decades, they have become its most dangerous and unattractive feature.

Normally, in most cities affected by smog, unhealthy levels of air quality persist during the winter months. In Lahore it now seems that it does not need to be cold for there to be smog but rather it simply needs to be not insanely hot. That is the scale of the problem we face. On Friday with temperatures still hovering above 30°C the average AQI in Lahore was 157. In more than one area it was over the 250 mark. By the evening, when all vestiges of the sun had given way to night, the average AQI in the city had risen to 176.

The figures may not faze an average Lahori. After all, for years the people of this city have been witness to the worst air quality anywhere in the world. According to the AQI scale, anything over 150 is unhealthy, anything between 200-301 is very unhealthy, and anything over that is straight up hazardous. Lahore has regularly seen AQI rating above 600 — double the amount at which it is hazardous.

To understand this, the air quality index is calculated based on averages of all pollutant concentrations measured in a full hour, a full eight hours, or a full day. The final calculation is made by averaging at least 90 measured data points of pollution concentration from a full hour. For Lahore to regularly measure well above hazardous is shocking, and the governmental and institutional apathy in response is criminal. To put things into perspective, in September 2020 the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality and Lane Regional Air Protection Agency released data that showed historical record-breaking air quality across the state following massive forest fires that left the state engulfed in ash and soot. The resulting AQI calculations that caused alarm and shock? Just under 500. Three months later, in December 2020, Lahore regularly capped this rating with no forest fires in the vicinity.

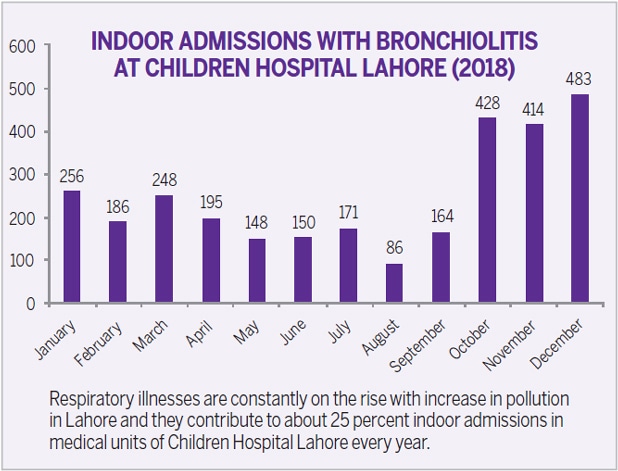

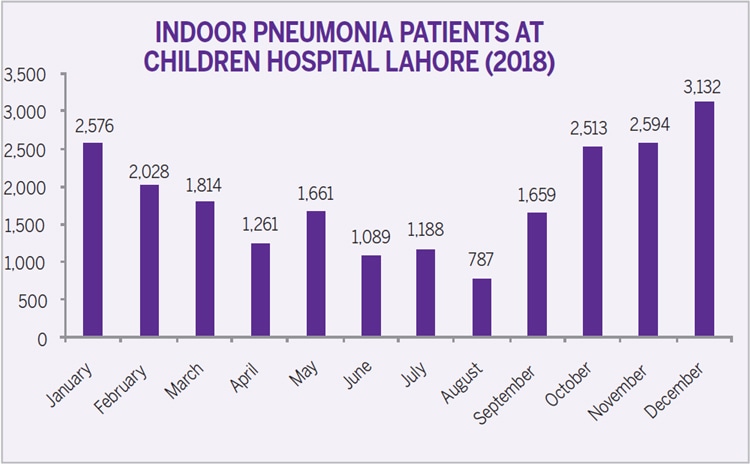

The scale of the problem is massive and its consequences will be dire in the years to come. Prolonged or heavy exposure to hazardous air causes varied health complications, including asthma, lung damage, bronchial infections, strokes, heart problems, and shortened life expectancy. A report in Dawn from back in 2019 points out how a 2019 analysis by the Air Quality Life Index produced by the Energy Policy Institute of the University of Chicago showed that long-term exposure to particulate matter air pollution was reducing the average Pakistani’s life by “more than two years.” And a 2018 study commissioned by Air Quality Asia, and carried out by Dr Junaid Rashid and Dr Shazia Manzur of Lahore’s Children’s Hospital, shows a spike in admissions for lung-related ailments during the smog season.

The ‘Global Alliance on Health and Pollution’ estimated in 2019 that 128,000 Pakistanis die annually due to air pollution-related illnesses. What is more alarming is that the statistics for the long-term damage that these prolonged years of smog will have on the health and lifespan of the city’s population are yet to even materialise.

Understanding the problem

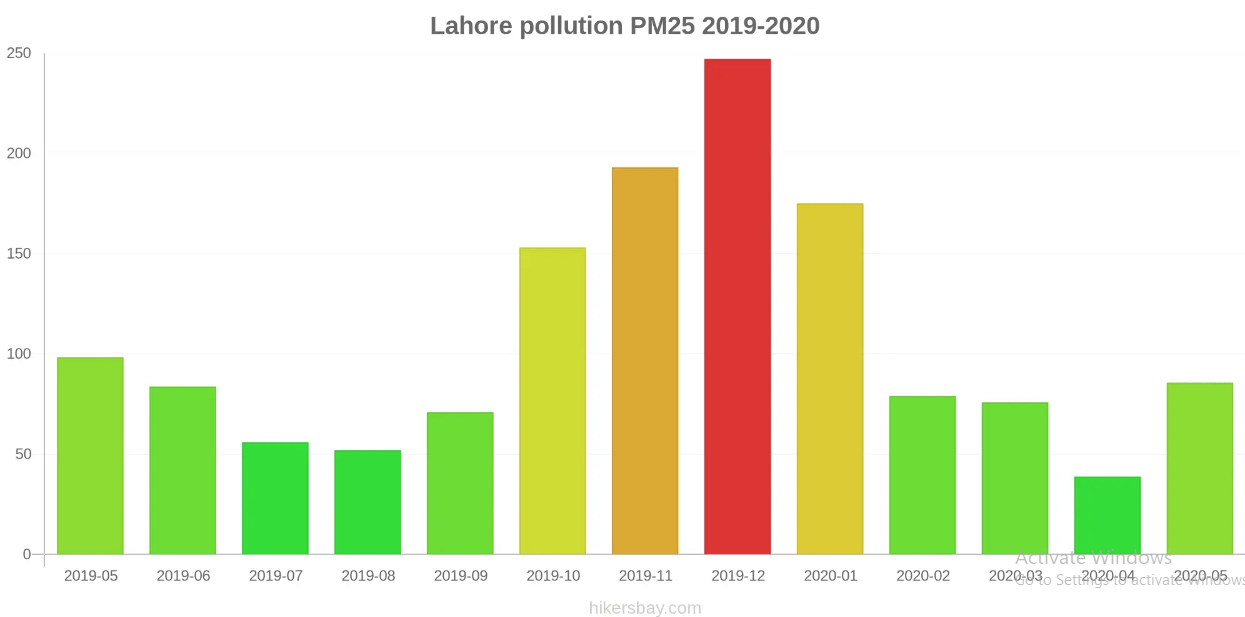

The major issue that cities like Lahore face is photochemical smog. In the winter months, smog occurs mainly when there is an excess of particulate matter and sulphur dioxide. Essentially, the amount of pollutants in a city’s air is pretty much at steady rates throughout the year. Emissions from cars and factories are the same in both the summer and the winter months. In Lahore, for example, the only significant difference between the summer and winter months is that crops are burnt in the October-November period which contribute to smog.

What happens in the winter, however, is that the air turns cold which means it also turns denser and is slower to rise above. Essentially, the entire city loses its ventilation. Think of it this way, if there are 10 people in a small room smoking with the exhaust fan on, the smoke is still harming the passive smokers but it is not hanging in the air constantly. Turn the fan off and you will have a hot-box that will be much worse for you. That is what happens to Lahore. Since the air becomes denser and heavier, it no longer takes the pollutant particles up with it causing them to hang around the entire city in sheets of smog.

Now, the question is where are these pollutants coming from and what have we done about it as of yet? “The smog in Lahore is caused by a confluence of metrological and anthropogenic factors,” said Saleem Ali, a member of the United Nations’ International Resource Panel. Namely, temperature inversion traps pollution in the atmosphere, which — alongside seasonal crop burning on the Indian-Pakistani border — combines with other sources of year-round pollution and fog to cause a spike in pollution and winter smog.

The reasons why air quality has been steadily declining in cities like Lahore are numerous. Vehicular emissions, industrial pollution, fossil fuel-fired power plants, the burning of waste materials, and coal being burned by thousands of brick kilns spattered across the province are all part of the problem.

Even these reasons, however, have been politicised. Many government ministers during the administration of different parties have claimed that a big reason for the Lahore smog is Indian farmers burning crops across the border. The reality is that crop burning seasons take place from late October to early November while the smog hits its peak in December and January.

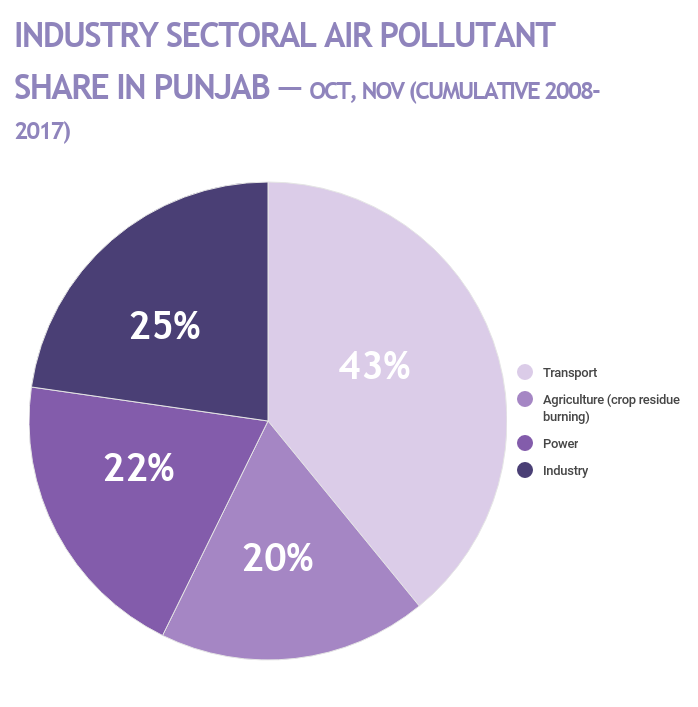

The real reasons are the emissions from vehicles and industries. In fact, agriculture related crop burning only accounts for around 20% of all pollutants while transport accounts for around 43% — with the rest coming from power and industry. Not only is Lahore a sprawling mess with no walkability and an insane dependence on cars and bikes for mobility, these vehicles use cheap fuel that does not comply with international standards and is horrible for air.

The lack of vehicular fitness and emissions testing, alongside use of poor-quality fuel, have compounded the city’s air pollution problem. Federal plans to switch to Euro 5-compliant fuel have faltered due to lingering economic troubles, including rising inflation.

What needs to be done

The reality of the situation is that we know what the root cause of the problem is. The city is filled with cars that have deadly emissions. It is close to unregulated industrial zones and perhaps worst of all it has been a problem that is consistently ignored because it goes away in the summer. There are two ways to go about solving this problem. To start off there are short term measures that must be taken to provide immediate relief.

Until a larger plan of action can be implemented, there are some things that the government can do. In a lot of European countries, restrictions of parking, reductions in speed limits, and pulling half the vehicles off the roads have been some of the more drastic measures.

Most cities justify these schemes on the basis that traffic is a major source of air pollution, and any action must help. Independent scientific evaluations are mainly restricted to the biggest cities. For example, data from Madrid and Paris shows that banning the most polluting vehicles can reduce traffic pollution by about 15-20%.

While these measures may seem unthinkable, there is merit to them working out. Last year, the Punjab government also passed an order instructing companies to tell their employees to work remotely to reduce traffic. Schools were also shut down. More such actions should be taken.

The only problem is that such short-term fixes will provide some relief, particularly to those with pulmonary vulnerabilities, they will largely be inconvenient and ineffective. In the longer run, better strategies need to be adopted. This means discouraging crop burning. This means reducing brick kilns. This means improving the quality of the fuel we use and finally shifting to Euro-5. It also means encouraging alternative sources of energy such as solar. However, the most important factor will be redesigning the city in a way that makes all of this possible.

A drastic revamp of the public transport, afforestation in dense urban areas, higher taxes on cars, distancing industrial zones, and plans to try and turn Lahore into a more walkable city will be vital to making Lahore liveable again. And that is what we must remember — it is possible.

Nothing new

This year, with the problem rearing its ugly, sulfuric head early even by its own hellish standards, it is worth looking at what can be done to address it both in the short and the long run. Because here’s the thing: this does not have to be our fate and it can be reversed. In many European countries, smog was a crippling problem that was fought off.

Thick smog used to frequently blanket the UK capital in the 19th and 20th centuries, when people burned coal to warm homes and heavy industry in the city centre pumped chemicals into the air. Referred to as “pea-soupers”, the most famous of these events was the so-called Great Smog of London in 1952, famously shown in the Netflix show The Crown. As a result, the Clean Air Act was passed in 1956, regulated both industrial and domestic smoke, imposing “smoke control areas” in towns and cities where only smokeless fuels could be burned and offering subsidies to households to convert to cleaner fuels.

Beijing is another example of a city successfully fighting back smog. China’s rapid industrialisation brought a huge rise in air pollution. Coal-burning power stations and a boom in car ownership from the 1980s onwards filled Beijing’s air with hazardous chemicals.

What was the solution? Years of hard work. A UN report this year shows that in the space of just four years, between 2013 and 2017, fine particle levels in Beijing dropped by 35%, while levels in surrounding regions dropped by 25%. “No other city or region on the planet has achieved such a feat,” the report says. But this was because of measures introduced and refined over the course of two decades, beginning in 1998.

This is an emergency

This is the most critical part of the equation. Up until now, the smog issue has been taken for granted. It has been written off as a phenomenon, or a new reality, or some kind of act of God. The government has responded with ad hoc actions to firefight the problem on a temporary rather than a sustainable basis. The utter failure of the administration to take durable measures to improve the air quality has inflicted severe, long-term harm on public health, putting people at greater risk for heart and lung diseases.

The truth is it is entirely created by our own irresponsibility. While larger goals like shifting to clean energy are important, in the meantime we must at least revamp Lahore and other cities to make them friendlier to the environment. Because as things stand, the consequences of this in the future will be dire.

Welcome to Versatile Coupons, the final location for getting a versatile deal on your internet-based buys. Our central goal is to assist customers with enjoying you find the best arrangements and limits on the items you love. We comprehend that setting aside cash can be intense, particularly while shopping on the web. That is the reason we’ve made it our objective to present to you the best-in-class coupons and markdown codes from top retailers. Whether you’re looking for garments, gadgets, or home merchandise, we take care of you.