Army-doctor-driven. Bumper-to-bumper genuine. No dent, no paint. If you’ve ever been sludging through the muck of the used-car market in Pakistan trying to find your next ride, these are some of the first things you will find proudly displayed in ads. Not whether the engine is in good condition or if any major mechanical or electrical work has been done on the car, but instead a strange obsession with how many little scratches and touch-ups a car has undergone in its lifetime.

It is a belief that stems from a long-held conception that in Pakistani society after God, family, and real estate there is only the automobile. Automobiles have long been considered a good store of value — even though they are a hedge against inflation. There is a long, twisty, history behind where this conception comes from. Put very briefly, it is because cars are imported in Pakistan and their prices fluctuate with the dollar. Which is why when you buy a car in Pakistan, one of the first questions you ask is what the resale value is going to be like in five years, and which is also the reason that when you’re selling that very car people on the second-hand market want it to be as close to ‘genuine’ as possible. Bumper-to-bumper of course.

It is a fact as sure as eggs are eggs. When you walk into a Toyota, Honda, or Suzuki dealership the salesperson will give you the same pitch each time “Sir yai gaari kabhi loss nahi de gi apko.” The only problem is that unlike Pakistan’s other investment obsessions, a car is neither a DHA plot, nor a brick of gold. It is a commodity, the ownership of which is deeply personal. If you ever talk to them about their own car after excitedly enumerating their favourite features they will first discuss keh petrol kum khaati hai, and then its resale value, and what a good and smart and intelligent investment they have made.

The asset class conundrum

You see, in Pakistan cars are considered to be an asset class. When a salesperson checks the car you’re about to sell him, his “bumper-to-bumper genuine” inspection is basically him looking to see if the asset has any impurities; almost akin to a gemologist peering through his microscope to check the purity of a gem.

But this is nothing new. Cars being treated as assets is as old as the automotive industry in Pakistan. While you are in the process of reading this, hundreds of cars will have changed hands on Lahore’s Davis Road. All the buyers and sellers will have patted themselves on the back for having bought an asset in these stressful times.

But what if we told you that this popular belief is trash? What if Profit told you that a car is, in fact, not an asset? Owning your first car is a milestone but to be able to buy one of your choice is a right of passage. Knowing what to look for, being able to make a decision based on factors that are important to you, is freeing, cathartic almost. But while it is all this, the decision is more often than not, also practical.

For example, one common denominator amongst all buyers is the resale value. It is understandable that everyone would want a return on their investment, but cars ‘normally’ fall under the category of consumer products. At least when you open a normal school textbook.

The world over when you buy a car, it depreciates. It loses its value year-on-year (YoY) and the value at which someone finally sells their used car, at i.e. disposable value, is usually lower than the price they bought it for. By a hefty amount in most cases as well. It is like any other thing you would buy, for example an iPhone.

It is not the same in Pakistan.

Here you can buy an old car, drive it, keep it for a few years, let it depreciate and still sell it for a higher price than what you bought it for. How is this possible? The gist of the matter pertains to the components used to assemble cars in Pakistan, and the volatility of the Pakistani Rupee. How much of an aberration are we looking at here then?

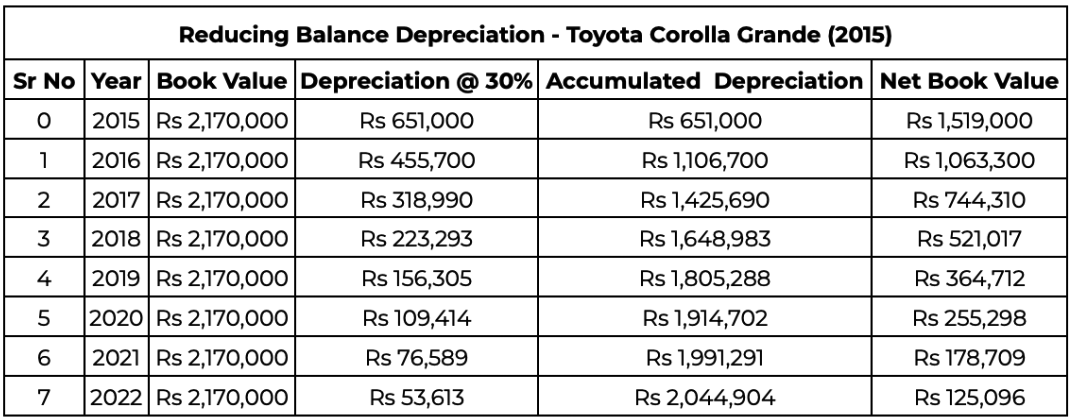

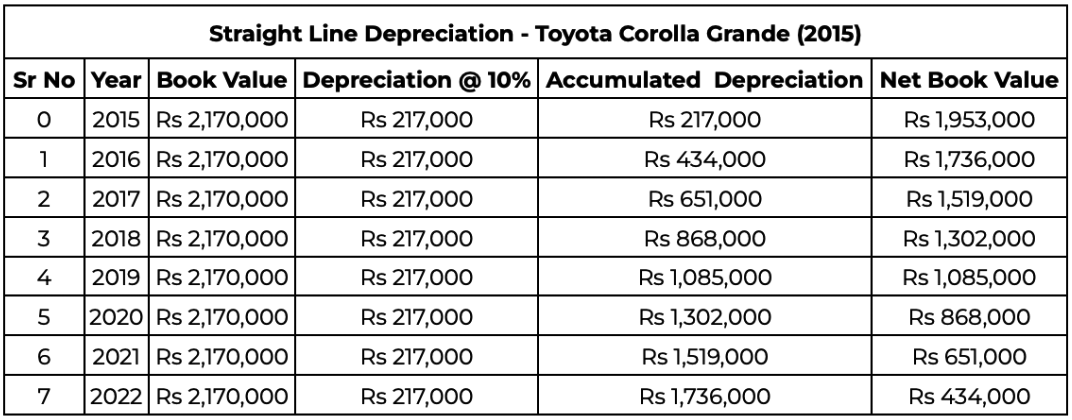

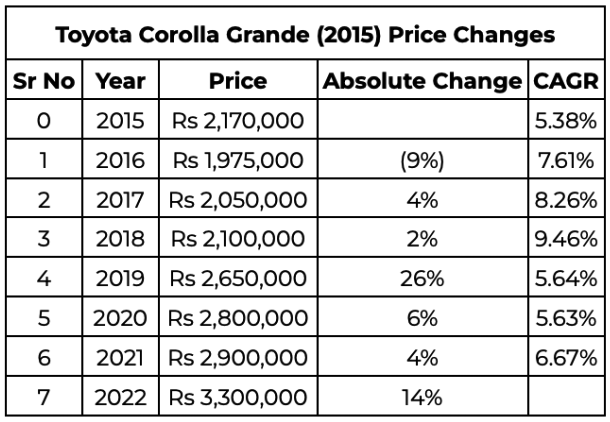

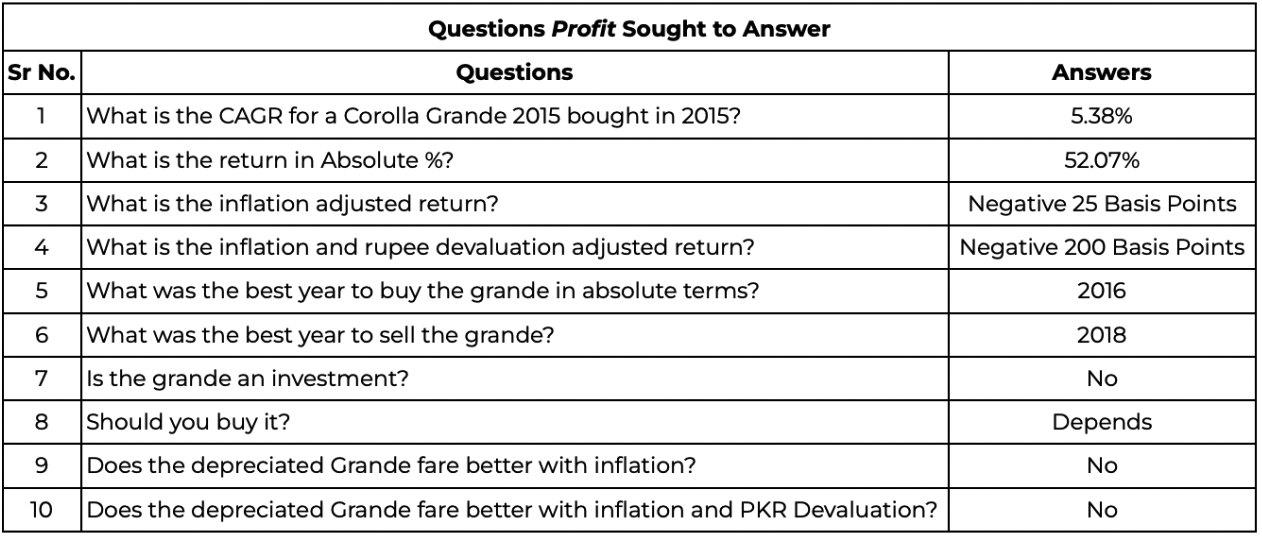

Profit looked at a Toyota Corolla Grande from 2015 to do the maths – It’s selling price at launch (2015) compared to its price in subsequent years till 2022. The price was obtained through market research in collaboration with automotive showrooms based in Lahore.

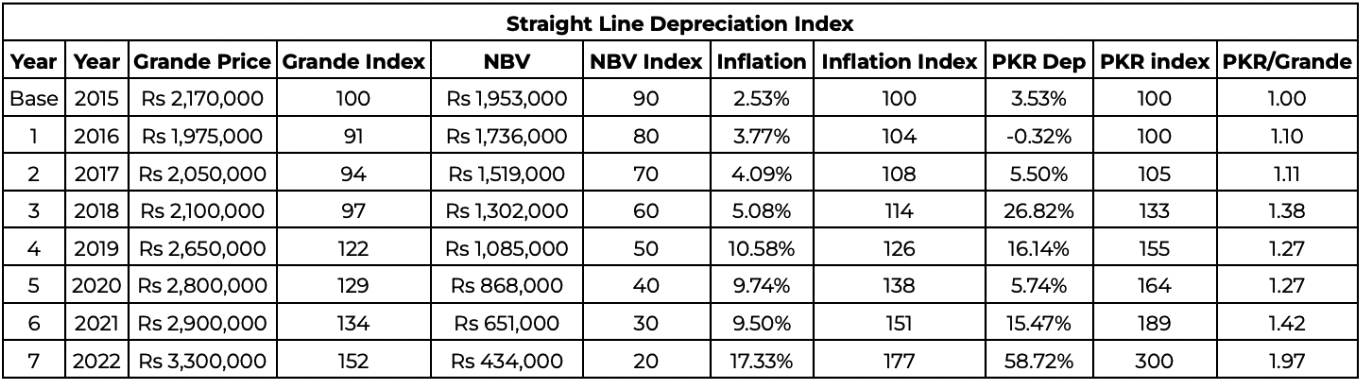

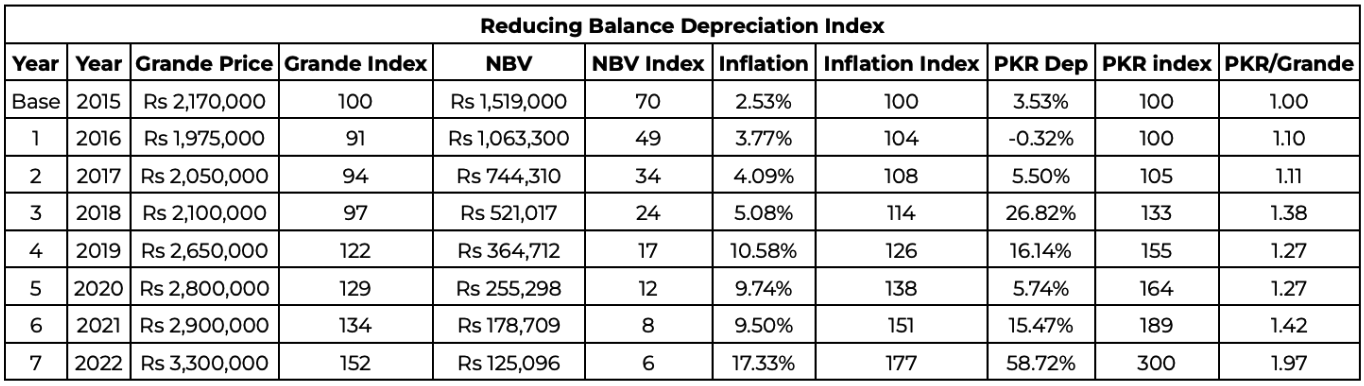

The Corolla Grande was found to be retailing between Rs 2.8 million to 3.1 million above its theoretical net-book value (NBV), depending on the method of depreciation (more on this later) used, in the second-hand market in 2022. What does Profit mean by this? Well, depending on which depreciation method is used, the Corolla Grande should only fetch a price between Rs 125,096 and Rs 434,000. In reality the car is currently being sold for a price of Rs 3.3 million.

The real question is, are there gains to be made? If someone had bought the Corolla Grande in 2015 and were to sell it right now, they would have made a return of 52.1% for a total of Rs 1.13 million in absolute terms. To put that into context, Rs 1.130 million is equal to more than half of what they would have paid for the car to begin with.

The Corolla Grande is able to achieve this feat as it has seen a price increase in six of the seven years following 2015. Depending on when someone picked up the Corolla Grande between 2015 and 2021 to sell it in 2022, they would have been able achieve a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) upward of 5% throughout the time period.

Appraising a car using these parameters makes it sound like such an enticing deal. You get a fantastic return on your investment. You get to fully enjoy your investment. But Profit is going to tell you that you ought to focus on the second aspect rather than the first because the Corolla Grande wouldn’t have beaten inflation or depreciation in any of the years we’re looking at.

In effect, you would have been worse off in real terms despite your gains in absolute terms. If this is sounding confusing, let us begin by looking at something people often miss when thinking about investments.

Why cars are not a good store of value

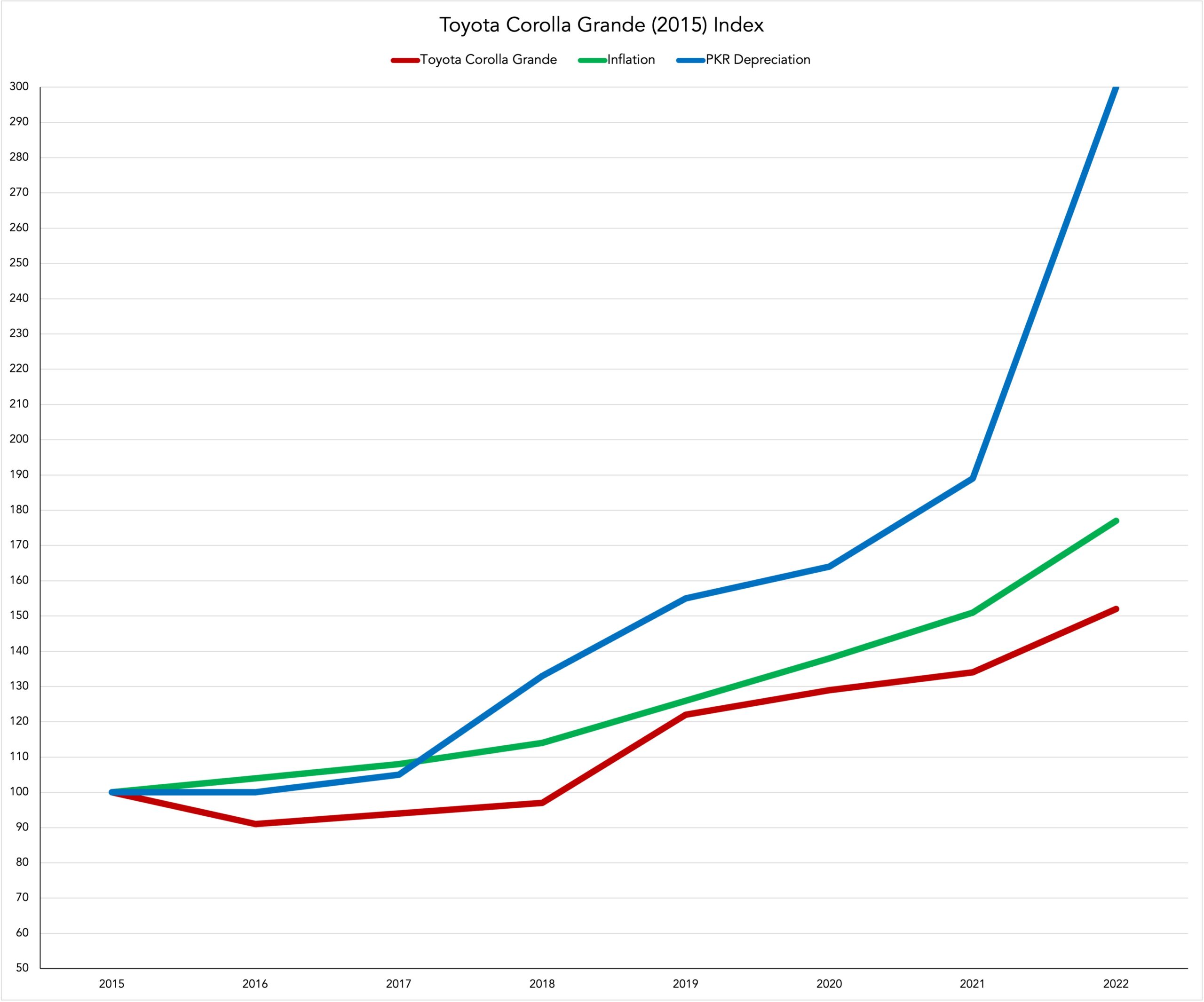

To explain the matter, Profit has created a price index for the aforementioned Corolla Grande and compared it with inflation and the Rupee’s devaluation.

The index has been created because of its utility in expressing data time series and comparing/contrasting information. Indices provide a simple way of representing changes over time. An index number is a figure reflecting price or quantity compared with a base value. The base value always has an index number of 100. The index number is then expressed as 100 times the ratio to the base value. Note that index numbers have no units, example Rs or $.

Inflation and the Rupee’s depreciation was acquired from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) and the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) respectively.

Why the Corolla Grande in particular, you ask? Well, beyond the cult status that it’s amassed, a Toyota Corolla is, perhaps, one of the most liquid cars/assets anyone can possess. The Corolla also had by far the highest sales numbers in 2015 when looking at the sales data provided by the Pakistan Automotive Manufacturers Association (PAMA). Using the Grande variant is just the frosting on the cake. Why the 2015 one? FY 2015-16 is the current base year for inflation employed by the PBS.

For depreciation, Profit utilised both reducing balance (RB) and straight line (SL) methods. RB is an accelerated depreciation system that results in declining depreciation expenses with each accounting period. In other words, more depreciation is charged at the beginning of an asset’s lifetime and less is charged towards the end. Whereas SL is a consistent depreciation system where there is an equal depreciation amount recorded throughout the life of the asset, as the cost of the asset is spread evenly for each year that it is used.

RB is most useful when an asset has higher utility or productivity at the start of its useful life. The depreciation expenses reflect the assets’ functionality. RB works for cars as its wear and tear, and maintenance costs increase at an exponential rate with the distance it covers in terms of travel. SL is most useful when an asset has equal productivity throughout the entirety of its life. Profit used this alongside RB as not all vehicle drivers are the same. Some travel far less frequently than others, and therefore the exponential increase would not be applicable to them. A mix of RB and SL allows Profit to capture drivers who fall under each category.

Cars in the Pakistani market tend to oscillate between both definitions so Profit utilised them for added measure and set an annual RB depreciation at 30% and SL depreciation at 10%. Finally, in terms of evaluating the return on the car, Profit utilised the CAGR, (CAGR is the average annual growth rate of an investment over a specified period of time longer than one year) because it takes into account the effects of compounding, and thereby incorporates the earnings/loss that arose in the preceding period as well.

With growth rate, you’re simply looking at the percentage change in an investment’s value over a specific period of time and not incorporating the preceding period to the principal amount. With CAGR, you’re looking at the investment’s average annual growth rate over a specific period of time. This is a more accurate way to compare investments because it smooths out the effects of short-term fluctuations.

Looking at the inflation adjusted return for the Corolla Grande for the entire period using the index, the Corolla Grande had increased by 52 basis points whereas inflation had increased by 77 basis points for a net loss of 75 basis points. The story is exactly the same for the entirety of the duration. The price of the Corolla Grande actually fell from 2016 to 2018 whereas inflation arose. It increased from 2019 till 2022, but inflation outpaced it every year during the period. Inflation on average beat the Corolla Grande by 12.5% year-on-year (YoY) from 2016 to 2022.

Adjusting for depreciation, the Corolla Grande fairs even worse. Looking at the entire period, the returns on the Corolla Grande had increased by 52 basis points whereas depreciation had risen by 200 basis points. As with inflation, it lost to depreciation YoY as well in terms of basis points. However, the difference between these two metrics is more stark than between inflation and the Corolla Grande. On average the car lagged by 36% in terms of basis points to depreciation from 2016 to 2021.

In simpler terms, if you wanted to beat inflation then the Corolla Grande is not something you should have bought. The same is the situation with depreciation. Buying the US Dollar rather than investing in the Corolla Grande would have been a better hedge against depreciation. Profit would like to highlight that depreciation particularly beat the Corolla Grande in 2022 because of the macroeconomic situation. A return to Daronomics may reduce the standard deviation from the rest of the years.

Now let us look back at the resale value of the Corolla Grande. If someone did want to know what the best year was to sell their Corolla Grande then according to Profit’s estimates it would have been 2018. There is no doubt that 2022 provides the best return in absolute terms as the Corolla Grande would have increased by a total of 52 basis points since 2015, but as of right now, the seller would have been the worse off in relative terms. In relative terms, inflation and depreciation are at the lowest edge in 2016 in comparison to the Corolla Grande.

You would have been worse off in any year but you would have been the least worse off having made the sale in 2016. This probably also answers the question as to whether the Corolla Grande was ever an investment. Nope. It wasn’t.

The question then is, should you have bought a Corolla Grande as an investment to begin with? Before we answer this question, let us discuss why we’re even looking at cars from an investment perspective to begin with.

Why are they considered to be a store of value to begin with?

Now, we’ve all heard about how cars are a good store of value. Right? Sales personnel will repeat the line till you walk out of the showroom. “Toyota pai aap kabhi loss nahi banatay” said a salesperson when Profit was deciding which car to use as the base for our story. However, for the uninitiated, who are wondering why this is a common perception to begin with, Profit has documented the entire matter in an earlier piece.

Read more: The lopsided market structure of the automobile industry

However, the tl;dr edition relevant to our study goes back to the nature of the inputs for cars and the nature of the macroeconomy. Irrespective of automotive assemblers’ claims of localisation, all cars in Pakistan rely on imported inputs in some capacity for several reasons. Cars in Pakistan are, thus a net, imported commodity, and their price is linked to the US Dollar. Subsequently, whenever the Rupee depreciates, which is a guarantee based on the past few years, the price of cars rises. Cars are, thus, hedges against inflation.

Furthermore, until recently, Pakistan has had very few players in the automotive space. Even now, for a country with a population that is in excess of 207 million, the number of players still pales in comparison to other comparable nations. Pakistan’s protectionist regime only compounds this by reducing competition. What all of this does is reduce the overall number of cars available in the country. This relative scarcity adds to the value of cars that do exist and therefore, limits the degree to which their value is eroded, relative to other competitive markets.

Such a market also makes it conducive for automotive manufacturers to factor resale value in their vehicle’s marketing plans. Automotive manufacturers thus proactively take steps to ensure that, at least in absolute terms, their vehicles do not fall prey to rapid devaluation in any manner. Profit has documented how companies and vehicles that forgo this aspect are then treated unfavourably by the market.

Read more: The KIA Sorento 101 – How not to price a car

Evidently, the snake-oils salesman of the auto industry never factored in relative returns that you would make when selling your car. This is likely not a result of any failing of his own, but customers simply just not asking him for the relative gains to be made from the sale of the car.

“This question is something different. It is an asset but not in a view of return on investment.” said Muhammad Iftikhar Javed, Business Head of Secured Lending at Bank Alfalah, when Profit asked if cars were assets to begin with and whether banks advise their clients to consider them as such.

“In larger scope of concept it is a “No” except for a certain part of the customer base who consider the car as a means of “forced savings’ ‘ to create an asset that they can later sell whenever they need the money.. These customers are mostly from small enterprises located in trading markets i.e. Shahalami, Azam Cloth,” he said. “Post 2012, the car prices increased and never dropped below the invoiced value so yes, people feel secure while having a car but it has never been adopted as a factor of investment or return,” he concluded.

Javed stated that his statement is limited to cars bought via auto financing. Profit believes that his explanation can be extended to customers who buy their cars primarily through cash. Auto-financing is by all means a method to bridge the gap between a customer’s available finance and the price of their desired vehicle. The reasons for why customers are buying a car to begin with are endogenous, and likely exogenous of the financial methods used to procure a car for the majority of customers.

It’s unlikely that salespeople will change their pitch to customers whether they buy the car through financing or cash. Both customer segments are equally likely to believe that they have acquired an asset that will be a store of value for them.

“It is an asset in Pak Rupees (absolute terms) but in real terms it is not, particularly not in terms of the US Dollar (depreciation),” says Suneel Munj, founder of PakWheels. It is important to remember that while we pay for cars in rupees, we in reality do so in dollars since they are largely imports. “Customers buy cars and try to sell them for a gain but then find out that the new car is four times more expensive because you have become worse off in US Dollar terms,” explains Munj.

That, of course, brings us back to the original question we asked; should you buy it then?

Putting a price on happiness

We started the piece by saying that you ought to enjoy your purchase because it is a car after all. Profit stands by it. Everyone who bought the car with the notion that it would be a good store of value, did benefit from its utility. Unless, of course you are part of the group of people who solely bought it with the intent to sell and locked it up in storage for a period greater than one year.

Unlike other ‘asset classes’ it’s not something that is locked away in a vault, a promise for a piece of land in an area you may never get, or a weirdly named security that your broker found for you. It is a car. Despite the fact that you are losing out on value, you have mobility, and that too in a vehicle of your choice. While you cannot place a price on that, practically speaking there is a price to pay. This is because depreciation methods do exist and because automotive companies have set a price on it.

But you can’t put a price on the happiness you will personally get, right? BMW’s already managed to monetise their heated seats after you purchase the car so maybe, at least not for the next few years.

is this an article ? a poor quality. no conclusion drawn no info. what a joke.

Its a fantastic article !

This Article is Awesome. It’s helped me a lot. Please keep up your good work. We are always with you and Waiting for your new interesting articles.shopmore.pk

Excellent blog. You have shared some wonderful tips. I completely agree with you that it is important for any blogger to help their visitors. Once your visitors find value in your content, they will come back for more.

have a good day.shopmore.pk

This article has excellent analysis and detailed information but unfortunately, I could not read it as it is pain to read this very haphazard collection of paragraphs without considering reader.

I once again find myself personally spending way too much time both reading and leaving comments

사설 카지노

j9korea.com

The analysis is good one, but you didn’t draw any conclusion? What is then a good investment in Pakistan? Are you suggesting one should stock away the wealth in dollars, without considering ethics or something?