Arey abhi to party shuru hui hai.

Uber’s acquisition of Careem is being talked about as a fairytale ending for a story about Pakistani entrepreneurship: smart young Pakistani entrepreneurs and executives – along with people from many other nationalities – built an amazing juggernaut of a company that was ultimately acquired by a much larger global competitor for a cool $3.1 billion, in the process creating 75 dollar millionaires and another 200 dirham millionaires.

There is certainly truth to that narrative, but in reality, it misses another, much more important, feature of the Careem story: it is the beginning of a transformation of the Pakistani startup ecosystem, the wider Pakistani business community, and – quite possibly – the structure of the Pakistani political economy itself.

What will happen over the next five years will lay the foundations for a fundamental transformation of how young Pakistanis see themselves, and what is considered possible in the Pakistani economy. And it will happen because, flush with the cash they have made from the sale of their shares in Careem, the founders and senior executives of Careem will become the first generation of Pakistan’s entrepreneurs-turned-venture-capitalists, marking the first time in history that Pakistani entrepreneurs will be seeking capital and advice from people who started off from middle class households and made it big in the startup world.

And that, in turn, will have significant consequences for the way business is conducted in Pakistan, particularly for the incumbents who have thus far chosen not to adapt to modern ways of doing business.

Consider this a fair warning, seth sahib: the startups are coming for you.

How and why do we think this will happen? Because this is what happens every time a major startup has a successful exit. And the story, like many things in the technology business, starts in Silicon Valley.

The making of Sand Hill Road

The beginnings of the cycle of what we now know as the venture-backed tech industry came about in 1956, in Northern California, when William Shockley launched Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory as a division of Beckman Instruments in Mountain View, California and recruited talented engineers with PhDs from America’s leading engineering schools to help him run it.

However, Shockley was not a particularly good manager of a business, and in 1957, eight of the employees of the new company – who became known as the ‘traitorous eight’ – left and sought financing for their own semiconductor company, seeking financing from bankers and other finance professionals from New York. Arthur Rock, then a banker arranged for $1.5 million in financing for them from Sherman Fairchild, the owner of a camera manufacturing company.

Thus began Fairchild Semiconductor, arguably the first venture-backed technology company in the world. And Arthur Rock, completely by accident, became the first banker-turned-venture capitalist.

Among the ‘traitorous eight’ were legendary names, including Gordon Moore (yes, that Moore of “Moore’s Law”), and Eugene Kleiner. In 1968, Kleiner would go on to invest in Moore’s then-startup called Intel. And in 1972, he went into partnership with a former executive at Hewlett Packard named Tom Perkins and start the firm Kleiner Perkins, the first dedicated venture capital firm that would go on to have its headquarters on Sand Hill Road, in Palo Alto, California, birthing the institutionalized venture capital industry, and creating a firm that would become one of the earliest investors in companies like Amazon, Google, Electronic Arts, Compaq, and Twitter.

This is a cycle that repeats itself several times over in the history of Silicon Valley: smart, talented employees of major companies feel stifled by their jobs and want to create their own companies and do something interesting in the world, but because they are not born rich, they have to go seek financing from somebody else.

Once they raise the venture capital, if they are truly talented, their business prospers and they are able to sell their shares in it for a massive profit within a few years. But because they are still relatively young, they do not just take the money and retire: they create venture capital funds that plow that money right back into the startup world to fund the next kid with no money, but good brains, a big idea, and a drive to succeed.

And then the cycle repeats.

In Silicon Valley, some of the biggest names in venture capital were originally some of the biggest names among startup founders. Vinod Khosla was a co-founder of Sun Microsystems before going on to create his own venture capital fund, Khosla Ventures. Marc Andreessen was the founder and creator of Netscape before going on to become a founding partner in Andreessen Horowitz, another major venture capital fund. And of course, Peter Thiel, one of the founders of PayPal, went on to become the first institutional investor in Facebook through his venture capital firm Founders Fund.

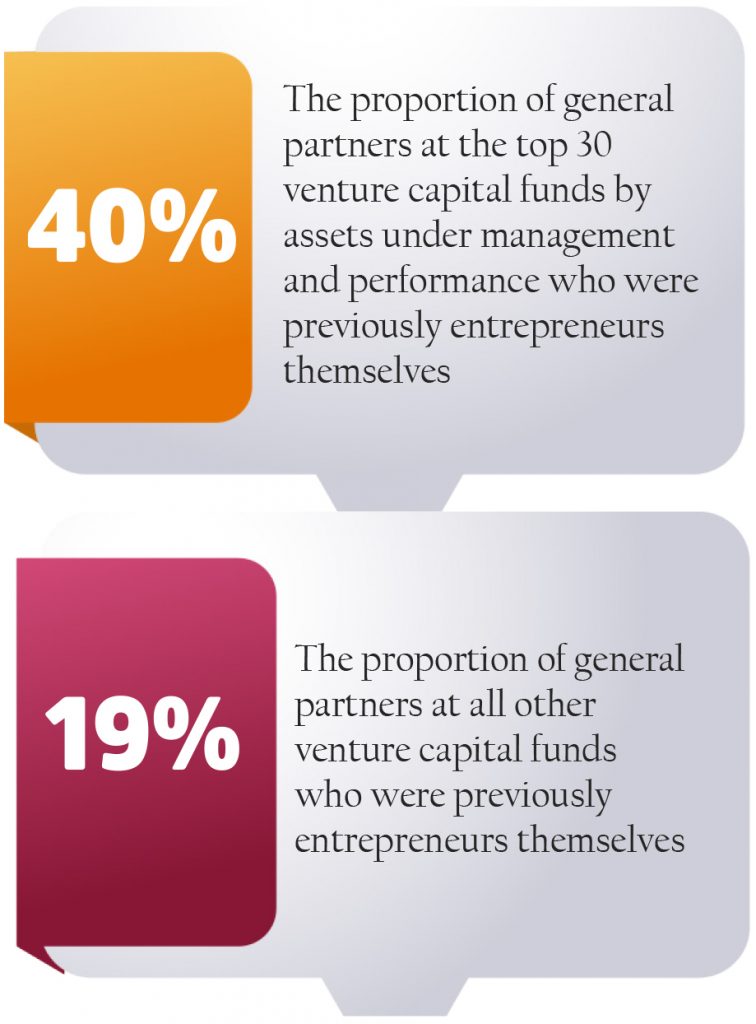

Indeed, according to research compiled by Endeavour Insight, a technology and entrepreneurship focused research firm, the single biggest factor that distinguishes the top 30 venture capital firms in terms of assets under management and fund performance from their peers is the fact that they tend to have a far greater proportion of entrepreneurs and former early startup employees among their general partners. Endeavour estimates that the top 30 firms, on average, have 40% of their general partners who were previously entrepreneurs, compared to less than 19% for other venture capital firms.

The VCs who backed Careem

In fact, among Careem’s original investors is a venture capitalist who started out just this way. On the board of directors of Careem sits a man who can be considered the original gangster of successful entrepreneurs-turned-venture capitalists of the Middle East: Fadi Ghandour.

Ghandour is a Jordanian-Lebanese entrepreneur born in Beirut and educated at the George Washington University in Washington, DC. In 1982, just one year after graduating from college, Ghandour started Aramex, a logistics and package delivery company. Over the next 15 years, Aramex grew to become one of the largest companies in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, and in 1997, became the first company from the Arab world to become listed on the NASDAQ.

Ghandour has been investing in startups in the MENA region for a decade now, and formalized his venture capital investments by creating Wamda Capital in 2014. Wamda Capital is one of the investors in Careem, and Ghandour is on its board.

While Wamda is by no means the largest investor in Careem (they joined in the Series C round), the existence of investors like Wamda – founded by entrepreneurs looking to find the spark in others that they had in themselves when they were starting out – is a powerful force in a startup ecosystem and a necessary one for it to thrive.

And with the Careem acquisition, that is what Pakistan is about to get: founders who invest in other founders.

Sources tell Profit that this may have already begun: Mudassir Sheikha is rumoured to have already invested $200,000 of his own money in 2018 into Pakwheels.com, an automobile classifieds website that has already changed how Pakistanis buy and sell cars. The investment is reportedly in the form of a debt instrument but is convertible to stock in Pakwheels.com.

And to understand why exactly that is so transformative for the Pakistani economy, it is first necessary to understand the current structure of how the Pakistani economy works, and whom it is designed to work best for.

The ‘contacts’ economy

Since its founding, the Pakistani economy has largely been dominated by a few wealthy families who all run businesses in conventional industries, and all of whom have extensive personal contacts and relationships with the country’s political, military, and bureaucratic elite.

To be wealthy in Pakistan means having contacts within the government, either to seek favours from the government for one’s business, or to have enough clout within the government to prevent it from blocking or slowing down one’s business plans.

There is nothing inherently wrong with having government contacts, or even lobbying the government for policies that one would like to see enacted. However, too often in Pakistan, it has meant seeking unfair advantages for the largest businesses while allowing the smallest businesses to fend for themselves, or worse, to suffer the consequences of the government’s favours for larger companies.

Careem’s founder Mudassir Sheikha, and its Pakistani executives like Junaid Iqbal, will likely become venture capital investors at some point, if not professional venture capital managers. If and when that happens, it will be the first time in Pakistani history that serious amounts of equity capital will be allocated not by those who were born into wealth and power, but by those who earned it on their own way to the top. Most importantly, it will be allocated by people who do not owe their wealth to political connections.

Of course, Pakistan has had many successful entrepreneurs from middle class backgrounds who went on to become very wealthy themselves. But some – like Malik Riaz – got there by currying favour with influential politicians and generals, and others – like Jahangir Siddiqui – challenged the order of the businesses they were in, but did not then return the favour and back others who would also be disruptors.

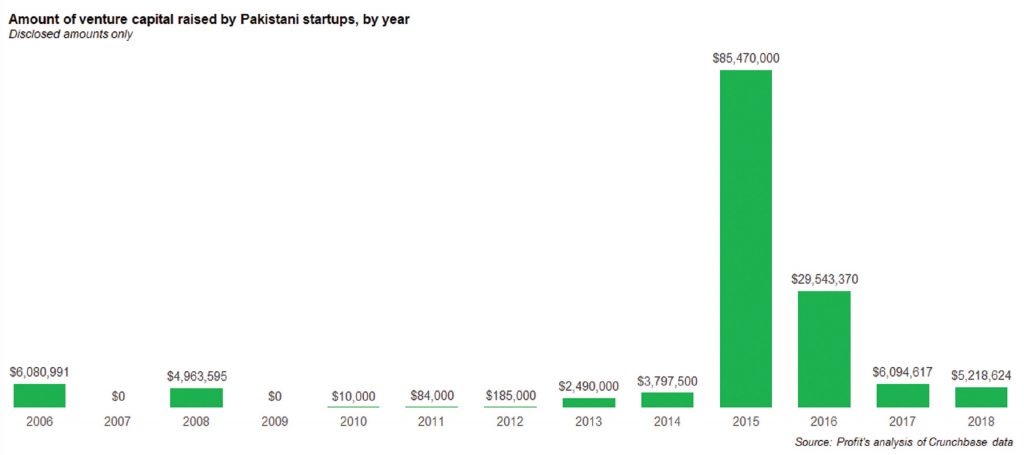

And Pakistan has had venture capital for some time now, and has at least a handful of professionally managed venture capital funds, such as Rabeel Warraich’s Saramacar Ventures. People like that will certainly continue to play a role in the evolution of the Pakistani economy, including nudging it in the right direction.

But the Careem founders are still different. They got to where they are without government favours or contacts, and they made their money by disrupting traditional businesses. And, crucially, they know how to see possibility where others see only risk and well-entrenched incumbents. That makes it highly likely that when they look to invest their newly-earned wealth, it will be in industries that do not require government contacts to succeed, and in companies that disrupt the order of established businesses.

And that is what makes this acquisition potentially dangerous for the traditional business powerhouses in Pakistan: for the first time, the disruptors will have serious cash to back them, and will be backed by people who did not come up through the system and do not feel beholden to it. And yes, while the current system is highly profitable for those who partake in it (rent-seeking exists for a reason, after all), people like Sheikha and Iqbal know that truly big profits come from unleashing the economic energy currently being suppressed by the sclerotic structure dominated by old-line companies.

Some older businesses will likely adjust and continue to thrive as they always have, particularly those who are smart enough to modernize their companies and give more autonomy to managers rather than retaining all control within the majority shareholding family. But others, particularly those who continue to think “This is Pakistan, this is how things are done here” will die off.

And good riddance.

It is for this reason that the Careem acquisition, far from being the end of a great story, is likely the beginning of something new, something bigger, something potentially much better than what Careem itself built. This could be become – should we choose to make it so – the start of the kind of Pakistan that we want to live in: one where the circumstances of your birth matter less than the scope of your talents, one that is not dependent on conservative old firms that do not invest in their business or their people, and one where we accept change as opportunity rather than reject it out of fear.

It could get very, very interesting in Pakistan over the coming few years. As we stated at the outset of this story, arey abhi to party shuru hui hai…

Well written

Comments are closed.