In December 2018, erstwhile finance minister Asad Umar, while chairing the first meeting of the steering committee, approved the implementation of the National Single Window (NSW) system in Pakistan by the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) Customs’ Wing. On May 28 2019, FBR Chairman Shabbar Zaidi revealed to a group of journalists and development partners that the NSW will become operational by 2021.

The announcements were met with great enthusiasm at a gathering of officials and stakeholders including Member Customs Operations Dr Jawwad Uwais Agha, World Bank Country Director Patchamuthu Illangovan, Project Director Imran Mohmand, and economists and resident officials from the Asian Development Bank. Everyone present touted the idea that the NSW will be helpful in improving trade and “provide a comprehensive solution for imports, exports, transit trade, trade through border customs stations and air cargo.” Project Director Imran Mohmand said, “The advent of global value chains and FDIs badly needed to boost Pakistan’s exports are closely dependent upon facilities like NSW which reduce border thickness.” According to those spearheading the project, this system has effectively reduced costs, time and complication for cross border trade wherever it has been implemented.

But what actually is the NSW? How it is expected to work? What is the likelihood of it working in Pakistan? And can it be expected to impact Pakistan’s export sector woes in any positive way?

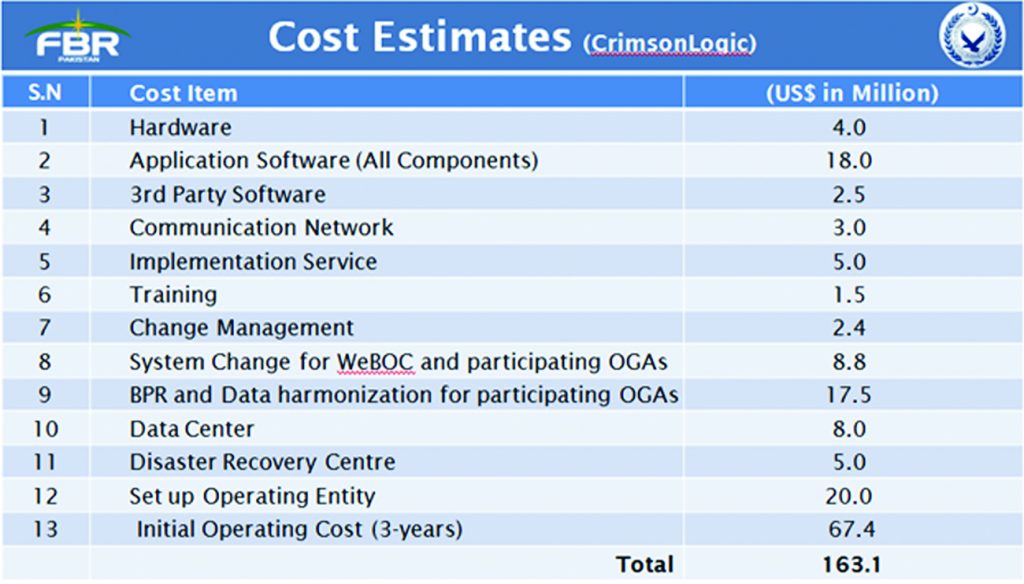

The project is to be completed at an approximate cost of $163 million (around Rs 25 billion or 25,000 million Pak Rupees). This is clearly a major undertaking. For context, the amount is equivalent to the money allocated for the Green Line Bus project (Rs 24.6 billion), approximately 5 times the funds given for the Karachi water supply scheme (Rs 9.6 billion), and almost three times the Prime Minister’s National Health Programme (Rs 8.179 billion). But where these projects, with their significantly lower funding, have clear goals for the public, the NSW still wades murky waters regarding exactly what it is supposed to do.

In response to this, the project director said “Due to the decision of indigenous developing the cost has been brought down $75 million. This is a meager figure as compared to $430 million annual savings that NSW can generate for trade.”

It is pertinent to mention here that the establishment of NSW system by 2022 is a basic requirement under the World Trade Organisation (WTO) Trade Facilitation Agreement to which Pakistan is a signatory. The question, therefore, is not whether to establish such a system or not, but what are the prerequisites that need to be included in the business plan before its formal approval to avoid it becoming another PSM or PIA, and what will its impacts be once it is in place.

Operational and Business model of NSW

The business model for execution and operations as well as alignment of participating departments had been approved by the Steering Committee back in April, 2019. The draft legislation for NSW has been prepared while the functional, revenue and technical models are expected to be finalized by June, 2019. Though the government has allocated funds in the upcoming PSDP, however, customs is currently providing funds from its GD (goods declaration) service fee to fast track the NSW implementation.

The operational model of NSW is such that 48 trade regulators have been, or are being, taken on board whereby all their operations will be conducted through the NSW. Under the new system, all 48 regulatory bodies are to retain their respective powers while their functions will be carried out through electronic access to the NSW. What will happen to the payments being made by the traders, whether they will go to the respective bodies, stay with NSW, or be divided in some specific proportion, is yet to be determined. Whether there will be a registration cost payable by the traders wishing to join NSW, and if so how much, is also to be decided. The details shared by those spearheading the project about how NSW is expected to earn were also hazy at best.

To understand how the business model of NSW might work – if decided and established properly – we can take the example of a similar single window operation from Singapore, which has proven to be a success story.

Singapore’s one window model is known as TradeNet and has been operational since January 1989. Back in 1987, it cost north of 20 million Singapore Dollars in direct capital costs for TradeNet (USD 10 million as per the exchange rate back in the day); [For NSW these are estimated to be $163 million today]. The business model then dictated that any company wanting to join TradeNet had to pay a monthly fee of S$20 (approximately USD 14) and per transaction cost of S$2.88 (approximately USD 1.99). (This has been a transition of a one-time connection fee of S$750 and a monthly charge of S$30 around the turn of the decade).

Assuming ceteris paribus for factors above and beyond the subscription fee, in Pakistani currency, this would amount to approximately Rs 2,000 monthly subscription fee and about Rs 300 per transaction, such as permit applications, origins applications and so on. NOCs (No objection certificates), licenses and other statutory requirements are a different game altogether, but they will certainly cost more than this. In a bird eye’s view, therefore, NSW does seem to have the potential to bring cost advantages for traders in Pakistan, since Rs 2,000 is surely far less than the logistical costs it takes for importers and exporters to travel to Karachi, Islamabad, and provincial capitals for clearances and permit applications.

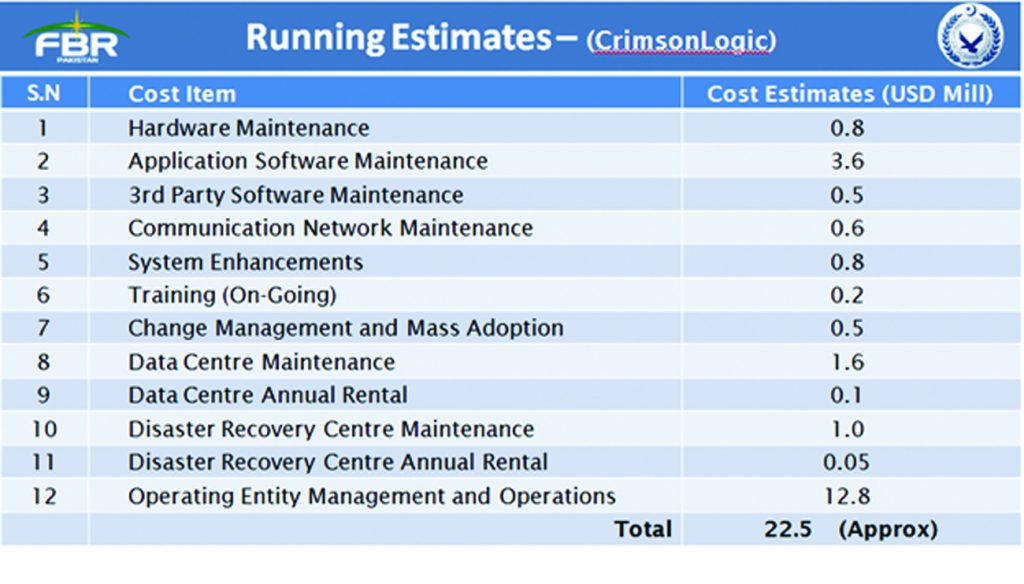

However, as of now the financial model of National Single Window is unclear – perhaps even to the organizers and managers themselves. During the event where the FBR chairman updated concerned parties with the progress of the project, Customs member Agha claimed that this one window operation will reduce the costs for every department involved, and will also bring about reduction in the costs paid by the traders. But his presentation only mentioned “cutting costs through reducing delays and informal payments”. At the same time, Project Director Imran was of the opinion that the fees charged to those facilitating from the NSW will make this model a self-sufficient one. The running cost estimates as given by the FBR are $22.5 million per annum, amounting to approximately Rs 3.3 billion. It is interesting to note here, that WB Country Director Patchamuthu Illangovan did not shy away from raising his concerns over another public sector entity being formed in Pakistan despite so many examples available of public sector projects bleeding money. He suggested that the FBR outsource NSW to a third party to prevent yet another organization dependent on state cash. Needless to say, the suggestion was not taken kindly by the Customs member or the FBR officials present at the time.

Project director said, “If NSW is outsourced (which is called the concessionary model) Pakistani traders will end up paying at least $150 million annually as NSW charges and fees to the public sector company. Also this will allow allow one foreign entity to control Pakistan’s trade.”

But does that discount the very real risks attached to the implementation of this new system? It is also notable that the Singaporean example is also a public-private partnership. In 2007, the Singapore customs adopted a public-private partnership model for the revamping of TradeNet. NSW can learn from its own mistakes from other projects, or learn from other countries for exact same projects and avoid all the financial ditches. However, if precedent is an indicator, it is likely to do neither.

The malady of exports

That’s about it for the future of NSW as an entity itself, but what is important to look at is the impact i will have on the public as well as the economic dynamics of the country. NSW from the very beginning has been dubbed a breakthrough in improving the trade climate of Pakistan. And that climate hasn’t always been very productive.

For starters, Pakistan’s imports are relatively inelastic. According to trade data report released by the Pakistan Business Council, one-fourth of our imports constitute petroleum products, (23.18% in FY2018 and 26.17% in FY2019), followed by machinery, chemicals, and food. Together, these categories constitute about 70% of our imports. Unfortunately, our exports also seem to have an inelastic demand with textiles making up approximately 60% of total exports. Why? Because for decades the overvaluation of Pakistan Rupee has been blamed as the cause of lack of competitiveness of Pakistan’s products in the international market. However, despite the devaluation of PKR, and even with incentives being offered by the government, the export figures showed an 11.13 percent decline in March 2019, as shown by Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. From a value of $2.227 billion in March 2018, exports fell to $1.979 billion in march 2019. This happened despite Pakistani currency losing almost one-third of its value against the dollar since December 2017, when our exports seemed to have hit the hardest blow. The problems are much rooted much deeper than just the currency value and the delays in the clearances – important as these factors may be.

Pakistan is lagging behind its neighbors and trading partners in economic growth. South Asia continues to be the fastest growing region with 7 percent growth projected for 2019, according to the World Bank’s economic update. However, Pakistan’s economic growth is expected to decelerate to 3.4 percent in the same time period, and even more so, by 2.7 percent, in the fiscal year 2020. The trade deficit is also projected to remain elevated during 2019.

Pakistan’s export products are highly concentrated into very few products – cotton, leather, and rice make up for approximately 70 percent of exported goods – and even most of these are intermediary goods instead of value added finished goods that fetch good money. This is perhaps the biggest deterrent to any improvements in our trade balance. Poor quality of infrastructure, outdated technology, energy shortages, and lack of incentives to gain competitiveness as opposed to dependency on tariffs are the root causes of low exports. At the same time, there has not been any concentrated effort to diversify the export market. The same six countries – United States, China, Afghanistan, United Arab Emirates, Britain and Germany – are being relied on for Pakistani products for decades. The idea of global value chains and regional integration either does not make sense to the Pakistani lawmakers and traders or they are simply not interested. Even our current export markets are contracting.

Our all-weather, higher than the Himalayas, deeper than the ocean, sweeter than honey, and stronger than steel friend China has also continued to reduce its demand for Pakistani yarn and fabric, since 2017 when competing countries began significantly undercutting their prices. China is also more inclined towards high-tech products now instead of low-tech products like textiles and footwear. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have also shifted away from Pakistan in exports of rice, according to statements released by the Ministry of Commerce. The shifts in export volumes and values of these products are not inconspicuous in our trade data, yet there seems to be no “investment” being made into targeting newer markets or focusing on improving product quality.

This is where the question of NSW comes in again. When asked how the NSW would deal with this crumbling in Pakistan’s export sector, Customs Member Agha no longer had the former glowing praise for the NSW and simply said none of this was his department’s job. “You should ask commerce ministry these questions. We are only here to enforce what regulators decide”. An economist with Asian Development Bank’s Pakistan resident mission, Farzana Noshab, however had something of an answer. “The time lags in clearance of consignments in Pakistan and the delays in communication elsewhere in the world is harming the reputation of Pakistani exporters so NSW will benefit exporters in that sense,” she said.

E-payments challenge

Then there is the obvious challenge of shifting from cash, cheques, and pay orders to online payments. NSW will also require a legal framework that enables and defines the conditions of electronic submission of documents, user authentication, data sharing and data archiving. Talking to Profit, after the presentation, Customs member Agha said that the 48 regulatory bodies brought on board will have to get rid of the hard cash and cash equivalent instruments. “We are in talks with all of them, on a daily basis. We also have 62 branches of National Bank of Pakistan on board with us and we are working every day to ensure that cash is done away with.”

There is no denying that unifying trade regulators and making the process of importing and clearance easier is something that is necessary in modern economies. However, if the ailments of Pakistan and its economy are concerned, NSW is just a posh decorative addition to a dilapidated house. The tangible impact of NSW will be to make the process of importing easier while adding more burden on the national exchequer to support yet another public entity – without making necessary reforms that can ensure income and revenues to support the very system as well as the larger economy. Even on its own, the business model of the National Single Window seems flimsy for now and unless proper management is put in place, there is little to be hoped from a model that can otherwise bring a great deal of transparency for the government and facilities for the traders.

Good effort on such an important issue. Keep it up !

Excellent article on an important issue. Without necessary reforms, instead of benefiting the businessmen, NSW may become a burden. We are already lacking behind our neighbors on so many fronts (education, economy, etc.) that we cannot keep doing things the same way we are doing currently and believe there will be no repercussions. On an individual level, yes everything may seem fine, but on a collective level we have gone below the level of African countries!!!

The writer has only focused on one aspect which is the cost of the NSW. Studies conducted by the OECD and International Trade Centre(ITC) indicate that Trade Facilitation Reforms while moving moderately could fetch around $ 1 trillion in increased trade to the WTO members. For the writer I would like to say it is $ 1000 billion worldwide. Moderate implementation of the Trade Facilitation Agreement(TFA) of the WTO say implementing the NSW could increase GDP of the World by a whopping $ 1600 billion. Needless to say that if Pakistan wants to benefit from such opportunity it would have to move in sync with the world and not sit idle and do nothing. According to the World Bank Group reports and ITC , the cost of importing or exporting a 20 Feet container for the best performing countries is on average $ 595 while for the worst performing countries like Pakistan, it is $ 2600. Such huge gap points to the fact that the worst performing countries-read Pakistan is losing around $ 2000 per 20 feet container in competitiveness. Reducing such a loss on account of tardiness on our part, requires automation. The OECD estimates that countries like Pakistan could reduce such cost of import or export by 17.4% if they implement TFA. In simple words, Pakistan can save around $ 450 per container if we implement NSW. Taking the figure of 2.1 million TEUs(Twenty feet equivalent unit) handled at Karachi Port during 2017, the amount of savings could reach $ 945 million in one year. In PKR on current exchange rate, it would come to 148 billion rupees. If we discount the time factor and only take the cost of import/export per container, as calculated by the World Bank in its Ease of Doing Business Report-2019 for Pakistan, the average cost of import/export of a container for “Trading Across Border” indicator is $ 615. Savings on this cost to the tune of 17.4% would amount to Rs. 35.8 billion per year for Karachi Port only. So we should expect a cost saving between Rs. 35-148 billion for Karachi Port per year, if we implement the NSW and Trade Facilitation Agreement.

Despite such evidence to the contrary, the writer seems to insist that we should live in the age of papers and red-tappism instead of going forward towards trade facilitation. Any action contemplated for the benefit of the people always draws opprobrium from journalists. We have become too cynical I presume.

Comments are closed.