Pakistan’s economy is going to contract this fiscal year, with GDP (gross domestic product) growth expected to stand at -0.38%, a significant decline even from last year’s anemic growth rate of 1.4%. Meanwhile, per capita income has declined to a seven-year low of $1,355 from $1,455 last year.

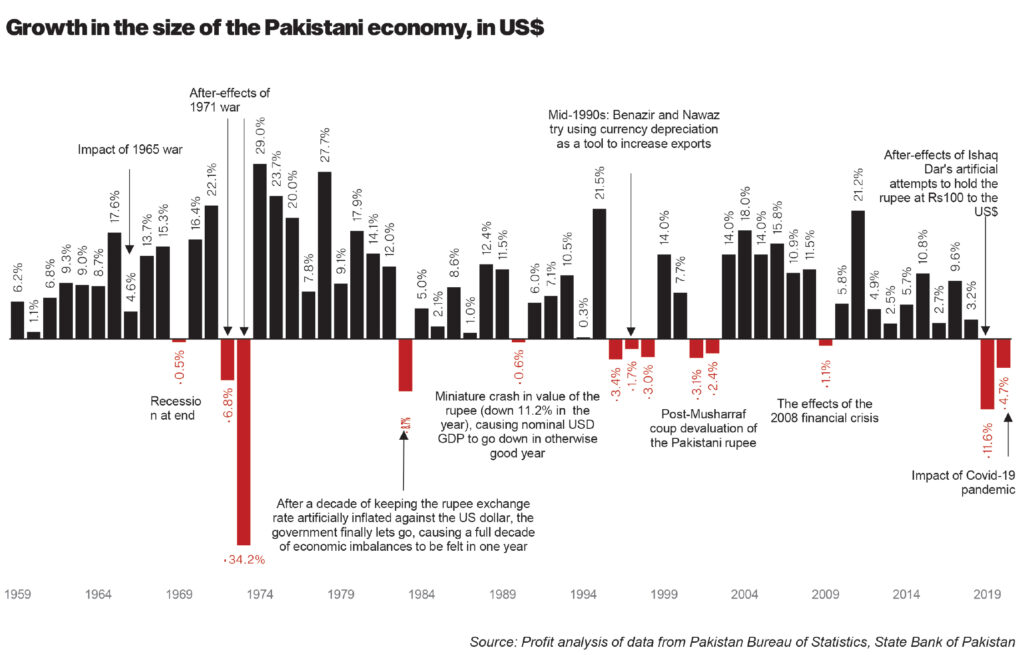

This is the first time the country will experience negative real GDP growth in 68 years. The last time this happened was in 1952, according to data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. To place that in context: growth did not turn negative even in the aftermath of the disastrous 1971 war. Which begs the question: how did we get here?

If the first answer you grasp for is “Covid-19, of course!”, well, yes. As Zeeshan Azhar, analyst at Foundation Securities pointed out in a note sent to clients on June 11, the Covid-19 outbreak and associated lockdowns resulted in a pronounced contraction during the last four months of fiscal year 2020.

But that is not the full picture. Let us first recap what happened before the crisis (if one can even remember a time that was not solely about the pandemic).

In July 2019, Pakistan had adopted the $6 billion IMF program, also known as the Extended Fund Facility. This three year stabilization program had actually begun to show fruit within the first eight to nine months of the current fiscal year.

In a note issued to clients on June 11, Umer Farooq, a research analyst at AKD Securities, an investment bank, noted that Pakistan’s macroeconomic imbalances had begun to ‘reverse their course’.

On the external front, the current account deficit narrowed 73% to $2.76 billion, in the first nine months of fiscal year 2020. In the same period, foreign exchange reserves held by the central bank rose from a low of $7.28 billion in June 2019, to $10.84 billion by March 2020. The rupee also managed to stabilize in that time, hovering between 155 to 160 to a dollar. This improvement was largely brought on by a decline in imports, which were down 16.2% year-on-year. Despite the rapid rupee devaluation, exports only grew 1% year-on-year.

Fiscally speaking, Pakistan also did much better. The country recorded a primary surplus of Rs194 billion, in the first nine months of the fiscal year 2020. Compare that to the deficit of the Rs463 billion in the same period of last year. Similarly, the fiscal deficit narrowed from 5.1% of GDP in the first nine months of last year, to 4% of GDP in the same period this year.

However, it is important to note that much of that improvement came on the backs on a rise of non-tax revenues. As Farooq noted, these were unusually high due to a one off licence renewal fee of Rs113 billion, and very high central bank profits of Rs635.5 billion (compared to last year’s Rs138 billion).

So, Pakistan was on track, fixing its twin deficits with very slow incremental changes. Then along came Covid-19, and derailed this entire journey.

“Pakistan’s economy like every other economy across the world was hit by COVID-19, thus making it incredibly tough for the authorities to achieve economic targets for FY20,” explained Farooq. “The gov’t has expectedly missed all major economic targets for FY20 by a wide margin”.

When it comes to calculating the GDP contraction figure, it helps to see each sector’s weightage. Services weightage is 61%, followed by the industrial sector at 19%, and the agricultural sector, also at 19%.

That is why any contraction in those two sectors is severely felt. Services contracted by 0.6%, compared to 3.8% growth in fiscal year 2019, while the industrial sector contracted by 2.6%, compared to a contraction of 2.3% last year. The only bright spot was in agriculture, which grew by 2.7%, compared to last year’s 0.6%.

The services sector, by virtue of having the most contact intensive business, was the most affected by the lockdowns. Wholesale and retail trade declined by 3.4%, while transport declined by 7.1% – a far cry from the 1.1% and 4.6% growth recorded last year.

Within the industrial sector, large-scale manufacturing declined by 7.78% year-on-year, due to a lethal combination of a rupee devaluation, utility rate hikes, and higher borrowing costs. Mining declined by 8.82% year-on-year, mostly due to a fall in consumption.

Agriculture, meanwhile, was driven by a 2.9% year-on-year growth in crops, and a 2.58% year-on-year growth in livestock.

Is there anything to look forward to (aside from a vaccine)? According to Azhar, agriculture may improve in 2021, considering it has a stimulus package, lower oil prices, and better water availability. However, as Profit has reported on before, locusts could derail that. The industrial sector will also benefit from lower interest rates, and new fiscal incentives and concessionary schemes.

However there is a concern about fiscal imbalances impacting Pakistan again. As Farooq points out, during a crisis, the government will want to spend more on its citizens, especially in healthcare and social protection. However, because economic activity has slowed down, there will be a drop in tax revenue. “We project FY20 fiscal deficit climbing to north of 10% of the GDP,” he notes.

What is certain is that 2021 is not going to be easy. The World Bank has projected a contraction of 0.2% for fiscal year 2021.