Given the surprising level of passion the subject of real estate can engender among Pakistanis, we shall start off this article by stating categorically what we are not saying. We are not saying that real estate is not a good investment and that you should not buy a home or seek to buy a home. We are not saying that you cannot make good money off of real estate. We are not even saying that other investments do not have drawbacks, or that real estate is an unstable asset.

We agree that, in general, it makes sense for people to try to own a home, and that an investment in real estate is typically an appropriate one for most people, and even that you can make good money off of it. With all those caveats aside, let us get down to what we are saying: Pakistanis invest a little too much in real estate, and we would be better off both as individuals (in the aggregate) and as a country if we diversified towards other asset classes.

The obsession with real estate has understandable foundations and originates in a fundamentally good idea: the need to buy assets that generate inflation-beating returns. But it has gone too far and is now starting to create a drag on economic growth, investment opportunities, and housing affordability.

In our analysis of the Pakistani real estate sector – which is notoriously difficult to find reliable data for – we have found the following: first, that it has generally been a reasonable investment for most (but not all) people who have invested in it. Second, that Pakistanis invest too much in it, and we have multiple measures to indicate that the investment in real estate is too high. Thirdly, we found that the over investment has consequences for real estate affordability, not just for low-income households, but for all households except the wealthiest. And lastly, we have found that all of the advantages of a real estate investment can be replicated using other, more economically productive investments as well.

One big caveat that readers should be aware of before reading this story: the author is the founder of a fintech startup that seeks to provide investment advisory services to individuals in Pakistan. While none of this article is meant to be a solicitation of investment advisory services, you should be aware of the incentives and potential conflicts of interest of the person whose writing you are reading.

With that, let us dig in.

Real estate as an investment

It is tempting to look at the data (whatever little is available on the sector) and conclude that something irrational is going on. Prices are much higher in Pakistan relative to average income levels across almost the whole country, rental yields are abysmally low for both residential and commercial real estate (though marginally better for commercial than residential), and there is no meaningful mortgage financing market to speak of for residential real estate, and a virtually non-existent one for commercial real estate.

One would be tempted to conclude that investing in real estate is an irrational decision that most people make based more on emotion than on hard evidence. Part of this perception is likely due to the fact that, for much of Pakistani history, hard evidence on the advisability of a real estate investment was hard to come by. The only real estate investments one could analyse were one’s own family and friends, which is hardly a representative sample of data from which to draw informed conclusions.

Over the past few years, however, Zameen.com – Pakistan’s largest online real estate portal – has collected a considerable amount of data on the sector and compiled an index that makes it easier to track the performance not just of one’s own real estate investments (which has always been possible), but that of the sector as a whole.

This article relies heavily on pricing data from Zameen.com and its real estate index, though we seek to correct for the upper-middle income-level bias in the Zameen.com data by using additional data on housing from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics on dwelling sizes and the relative distribution of them.

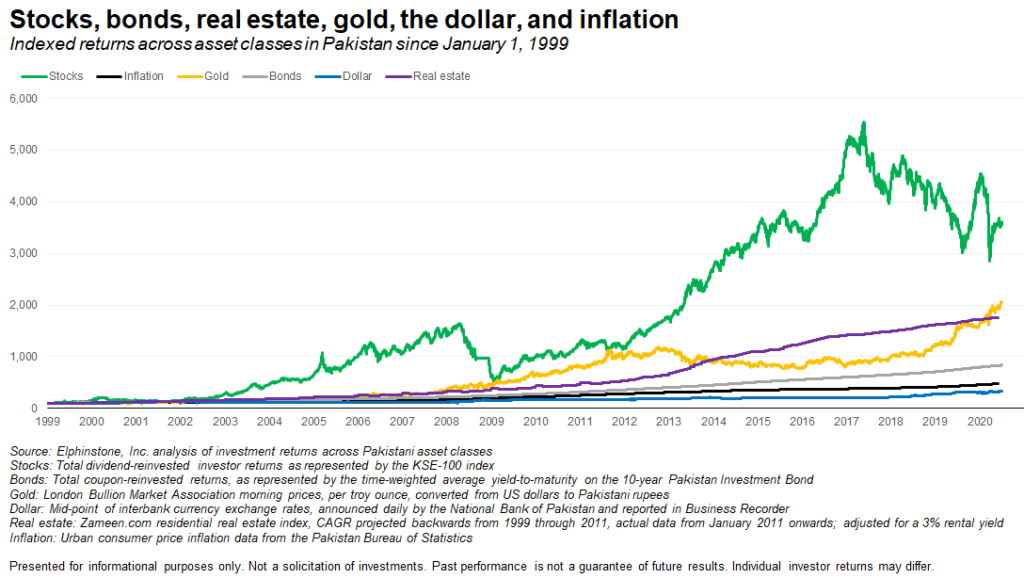

We compared real estate as an investment to other asset classes: the stock market, gold, government bonds, and foreign currencies, and compared all of these investment categories against average inflation. We compiled an index to show average returns across these asset classes in Pakistan since January 1, 1999 through the end of June 2020.

What we found was that real estate was the third-best performing asset class available to ordinary Pakistanis, behind the stock market and gold.

(Gold’s performance as an asset class is a little inflated right now owing to the fact that the commodity is priced in dollars and the Pakistani rupee has just taken a massive hit to its value, combined with a global run-up in gold prices. We believe over a longer period, gold is unlikely to sustainably outperform real estate.)

Over that 21-year period for which we have data, real estate has yielded an average annual price increase of approximately 11.3% per year. (Zameen.com’s data only goes back through January 2011; we have projected real estate prices backward to 1999 using the company’s data.)

This price appreciation is comfortably higher than inflation, which averaged 7.6% during that same period. But what makes real estate even better is that it does not just result in inflation-beating price appreciation: it also generates rental income.

Data on rental income is difficult to generate, so we analysed a large sample of properties for which we could find Zameen.com sale price data and the looked for comparable properties for which we could find rent data. This is an imperfect methodology, but it resulted in rental yields – defined as the annual rent divided by the total property price – of between 2% and 4%. We assumed that the average rental yield for residential real estate in Pakistan is approximately 3% per year.

So that would take the total average returns on real estate to 14.3% per year if one combines the price appreciation with the rental yields.

If one had bought a Rs1 million (Rs10 lacs) property that yielded the same returns as the national average, that property would be worth Rs9.4 million (Rs94 lacs) today. In addition, it would have yielded Rs8.3 million (Rs83 lacs) in rent over that 21-year period ending June 2020.

For context on the power of compounding, and how even slight differences in growth rates can yield big differences over time, consider the following fact: to have the equivalent value of Rs1 million in January 1999, one would need to have Rs4.8 million towards the end of June 2020.

In other words, that real estate investment would have comfortably beaten inflation.

But are we overdoing it?

Those numbers suggest that Pakistanis who park their money in real estate are being completely rational. They want an asset that is stable, and can beat inflation over time, and even generate a bit of income. Clearly real estate is doing the job. So, what is the problem?

Well, for starters, yes, it is doing the job, but there can be such a thing as overdoing even a good thing. Just because real estate is a good investment does not mean that one should invest everything – or almost everything – one has in that asset class. But before we even say why over-investing is a bad thing, let us first examine the extent to which Pakistanis over-invest.

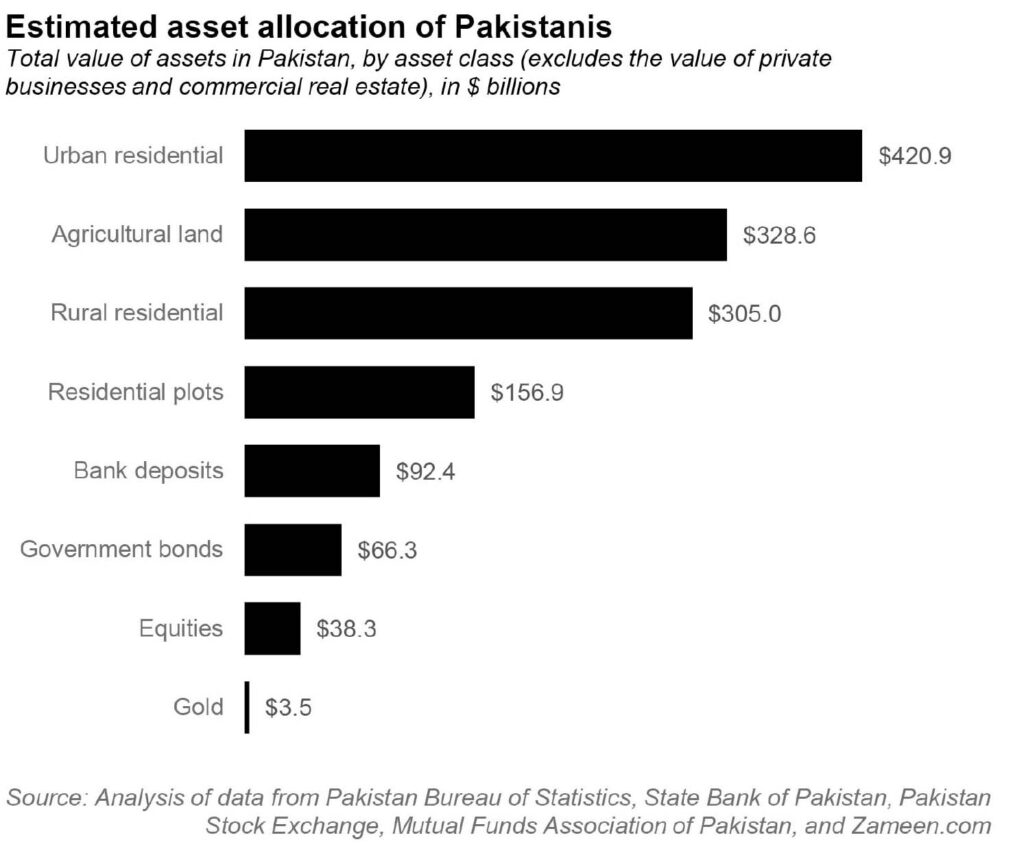

Based on a combination of Zameen.com and Pakistan Bureau of Statistics data, we estimate that the total value of all real residential estate in Pakistan – urban and rural houses and apartments, and residential plots in urban areas – is approximately equal to $1,211 billion.

We arrive at this data by using Zameen.com pricing data, PBS data on the distribution of rural and urban dwellings by size, and a sample of Zameen.com data on the square footage of dwellings by number of rooms (to map onto the size distribution data from PBS). This is, by no means, an exhaustive estimate of the total value of real estate, but we believe we are in the approximate range of accurate.

That number means that the total value of residential real estate holdings of Pakistanis is equal to 3.3 times the gross domestic product (GDP, or the total size of the economy) of Pakistan. For context, in the United States, the total value of all real estate in the US is equal to 1.6 times the US GDP.

Now, there are several quibbles that people can have with this data. For starters, Pakistan has an unusually large amount of empty residential plots compared to the US (this is anecdotal based on the proportions of listings of homes in Pakistan relative to plots on Zameen.com and comparing those with similar listings on Zillow for the US).

So let us exclude the data for residential plots and look just at housing, which comes out to $726 billion, or about 2.74 times the GDP. That still implies that Pakistani residential real estate is overvalued by 67% and prices would need to come down by approximately 40% to reach the same levels as the United States relative to GDP.

One might argue this is not entirely a fair comparison. The United States is a developed economy with its own dynamics and Pakistan is a very different economy as well. There is also likely a far higher proportion of the Pakistani GDP that is undocumented compared to that in the United States.

Fair enough, so let us consider another methodology of valuation that does not rely on GDP or any other economy at all and instead looks at the intrinsic characteristics of real estate within Pakistan itself.

There is, for instance, a very wide gap between the amount of money a property can generate in rent and the amount of money its owner would have to pay in a monthly mortgage payment, assuming a 25% down payment (standard requirement at Pakistani banks) and a 12% interest rate (the average interest rate over the past decade) on a 20-year mortgage (the longest duration allowable by most Pakistani banks).

The numbers are not even close.

Based on a sample of data we collected from Zameen.com, we found that the average urban property rents for about half the amount of money one would need to pay on a mortgage in order to finance the property.

And by the way, we ran numbers across the full 20 year mortgage: the initial difference is so wide that even with rent increases, the total amount of rent collected over that 20 year period usually does not end up equal to the total mortgage payments. (We did assume some variation in mortgage interest rates, based on the pattern of the past 10 years.)

That disparity implies that Pakistani property prices are about twice what they should be and would need to decline by approximately 50% in order to get to a level where they can be conveniently financed.

Note the similarity between the two methodologies on how much we estimate Pakistani real estate is overpriced by: anyway you think about it, Pakistani property prices are too high. And they are too high because Pakistanis are putting too much money into real estate, mainly because it is the only inflation-beating asset class that everyone can trust.

So what, you might argue? If I am making good money, why not continue? Two reasons: it is bad for you, and in the long run, it is also bad for the country.

Why is it bad for you? Because a lack of diversification can be a massive problem, particular when one approaches the age where one actually needs to start spending the money they have saved up. And I will illustrate this with the example of my father.

About seven years ago, I convinced my father to sell a plot he owned in Karachi and invest that money into the stock market. Without disclosing how much he received for that lot of land, I can tell you here is what happened next. My father sold that land and I invested that money on his behalf in blue chip stocks (this can also be done through the use of equity mutual funds if you do not have expertise in the stock market.)

Over the course of the next seven years, my father paid for my brother’s wedding, my sister’s wedding, part of my wedding, and bought himself a nice car, and still had the same amount of money that he did when he first gave me that money to invest. The profits from his investments paid for everything.

More importantly, as with land, when you have a big expense coming up, there is no option but to sell the whole thing. And if it is a bad time in the real estate market, but you really need the money (like last year, when it was a terrible time to sell, but suppose your child is getting married and you need the cash), you end up selling at a deep discount.

That gets to the heart of the problem of overinvesting in real estate: it is illiquid, and therefore less stable than it looks. Because it takes time to sell real estate, if you need cash quickly – say in a few days or weeks rather than months – it can be difficult to get the full price for the property, and one might have to take a substantial haircut on the price in order to get the cash when one needs it. That’s the problem: real estate prices tend to stay stable – certainly more so than the stock market – but stable prices do not mean that one will be quite so lucky when it is time to sell.

We want to be clear about one thing: home ownership is a worthy goal and most people absolutely should try to own at least one property that they would be comfortable living in, if you can afford it (more on what constitutes affordability below). But anything beyond that should be seen as any other type of investment, and therefore real estate should be considered the same as just any other asset class: your decision to invest should consider all of the options before you deploy your money.

As we will demonstrate later, many of your non-housing needs are likely to be better filled with other types of investments rather than continued investment in real estate.

There is, of course, the larger consideration on what so much over-investment in housing does to housing affordability, and how that impacts the wider economy.

The great affordability crisis

A lack of housing affordability is something that has plagued most economies in recent years, but even by global standards, the situation in Pakistan is really, really bad.

According to data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics’ Household Integrated Economic Survey, the average urban Pakistani household had 1.9 earners and had a combined household income of around Rs53,000 per month. That translates to Rs636,000 a year.

Now let us take a look at the average urban house/apartment price, which, according to our estimates based on PBS and Zameen data, is about Rs11.7 million (Rs1 crore, 17 lacs), or about 18.4 times the average income. By no stretch of the imagination can the average household afford that average house.

Here is what happens when the average household cannot afford the average house: either that average person looks for ways to stop being average, and dramatically increase income (and sometimes is willing to cross some legal and ethical lines to increase that income), or they decide that they do not really have a stake in the country. They either try to leave the country, or if they stay, they tend to not have much of a civic spirit, which is why most Pakistani cities – barring Lahore and Islamabad (and those because the people who control the government live there) – have a dilapidated look about them.

Personal finance experts agree that a house price should generally not exceed four times a person’s annual income. If you live in Lahore, Karachi, or Faisalabad on a household income of Rs53,000 a month, you can afford a Rs2.5 million (Rs25 lacs) home. There are some reasonable properties in that price range, but not very many.

And that, by the way, assumes that this average person has the kind of savings they need to put a 25% down payment on that home and then qualify for a mortgage on it, all of which – while theoretically possible – is practically a bit difficult.

So what does a person do when they cannot afford to buy their home? They do what the vast majority of Pakistanis do: they never leave the family home. Sometimes, if they are lucky, that home belongs to their parents, but often it can belong to their grandparents, meaning they have at least three, sometimes four generations living in one place.

It does not matter how big the house is (or how big the dil are), at a certain point, things start to get crowded.

One argument against pointing out the fact that young people cannot afford their own homes is that it will fray the social fabric of joint family households. But look around: by definition, joint family households eventually split off into multiple households. There is a reason why most people are not living with their fourth or fifth cousins.

So what is the appropriate point? Our contention is that the time at which families decide to get their own house is less determined by social dynamics and more by money. Most traditional parents in Pakistan would be offended if their child wants to move into their own apartment in the same city if they are renting. But change that situation to buying, and they are likely to be proud of their child.

People want to buy homes and their families want them to buy homes. But too many of them just cannot afford them because too many people are bidding up the prices. That, in turn, also creates a housing shortage and means that the housing-related sector of the economy – construction, materials, etc. – is far smaller than it should be, which in turn has a cascading effect on the rest of the economy.

What else could you be investing in?

So if not real estate, what else could you be investing in? The answer is obvious: stocks and bonds, both of which have the added advantage of financing businesses, and therefore the creation of economic activity and jobs.

Here is a simple principal to remember: if you are saving money for something that you will need to spend on in 10 years or more, you should probably be investing in stocks in order to save for that purpose. So, for instance, say you are 35 years old and are fortunate enough to have saved Rs1 million that you want to dedicate for the expenses related to your child’s education. Your child will go to college in 15 years and you want to be ready.

In that situation, do not put that Rs1 million in a plot. Over 15 years, the expected value of that plot will be Rs7.5 million, but of course, inflation will have taken its toll too. Based on historical averages, one would expect the rupee to lose two thirds of its purchasing power. Because of the way mathematical compounding works, the inflation-adjusted price of that plot would be more like Rs1.6 million in today’s terms.

By comparison, if you invested that money into stocks through a well-diversified mutual fund, the expected value of your investment in that stock portfolio would be Rs12.2 million in 15 years. In inflation-adjusted terms, that would be the equivalent of having Rs4.1 million today.

Of course, past returns are no guarantee of what will happen in the future, and stock investing is more risky than real estate investing, but look at the difference in profits.

And stocks have the added advantage of funding some of Pakistan’s best companies, helping them finance their expansions and creating jobs.

Indeed, stocks outperform real estate by so much that you could invest half your money in stocks and the other hand in government bonds, and still have a portfolio with the same capital gains and higher cash flow yield than real estate, with the added advantage of liquidity, meaning you would not need to sell the whole property just to use a small amount of the cash proceeds.

In short, the only property one should consider essential to buy is a home to live in. Any other properties are not essential, and likely to be outperformed by other asset classes, especially stocks.

Interested in getting your monthly reports

How can I read this article completely. Do I have to pay for this?

One of the best website. I like this blog so many information related to real estate. So much informative thanks for sharing such a fruitful info.

Well we are also working on hash residency The mission of Hash Residency is to provide an ideal living & commercial place for the clients who trust us the more. Furthermore, the hash Residency is based on a very unique theme & idea. The Hashi Group of companies & Hash Real Estate & Builder effort is to work in the best interest of the clients as they want & to keep the requirements & needs of the clients.

Interesting article. Very compelling.

I think level of education has to do a lot with over investing in real estate. As not everyone with money can invest in stocks or bonds but can do in realEstate.

I would differ a little, even Ph.Ds are members of plot mafia. This is rather a finanical literacy problem!

One of the very interesting and precise articles I have read in recent times. Well done.

Thanks for sharing.Such a great website.We are also providing best investment opportunity for investor.

This was a very insightful piece on how real estate has been engraved in our heads as the end all be all to investing. I love how you provided counter arguments to your own points and look at both sides of the coin. Profit is definitely my go to fix for Pakistani news, especially financial news.

people who are interested in investing in real estate sector of Paskistan specially in ISLAMABAD , i could offer you very attractive ROI over investment … please feel free to contact me at +92 300 3388815

Its help me alot in my Research proposal

Thank you so much

Before investing your hard-earned money, spend a fair amount of time in devising a holistic strategy for your real estate investment.

Best digital marketing company in Bahria town Rawalpindi Islamabad. Thanks for sharing such a beautiful information.

The only leverage I’ll credit your opinion about returns on investment of real estate compared to bonds or other mediums is your personal experience (of your father’s investment diversification)..

You have ignored the monumental benefits of a ‘timely’ real estate investment made on early bird investment rates or off-plan properties in project backed by a solid developer and expertise, it can (and has) given investors an ROI of 60%-80% in only the first year!

With bank mortgaging now on the rise (And Meezan Bank has already started rolling out Home Mortgages) you now have a buyer who can spend little of his own savings as upfront payments and build an asset over time. An asset that can give them great capital gains if it is invested at the right time. The real estate industry as a whole is going to see more demand and supply in the coming times because of the current exclusive drive and focus of the government.

The article has quite literally ignored the basics of pricing I. E. Demand and supply

Market forces correct these ataomatically, however if supply is a constant issue then prices would be forced upwards.

Now if there is a shortage of 8.2mn houses and increasing at the rate of almost 1mn houses per annum, who would not gain under such circumstances? And beg to differ with your findings, that if prices are 50% more here, how can ROI be in the mere teens? Just doesn’t add up.

Apni fintech na chamkao!!

My personal experience: I invested 3mn into a project in 2016. Rolled it over, in 2 different projects and made a plot, now worth 7.5mn, plus covered my brother and sisters wedding, served my home and had 2.5mn in cash at the start of 2020. That’s like around 400% + over 4 years.

Man what are you on about? the whole point is that the demand generated by “investors” drives up the price of as asset that is also a necessity and hence there exists such a huge disparity between average incomes and average home prices.

You are actually proving the author’s point by pointing out the shortage of houses. The shortage exists not because we are out of land but because homes are not affordable to even the middle class let alone the lower class.

I don’t even know what you mean by “that if prices are 50% more here, how can ROI be in the mere teens?” that makes absolutely no sense whatsoever.

good for you but that represents the problem. people like you, who clearly have no financial literacy over-invest in real estate because even a monkey can invest in real estate in Pakistan and make money. This however, is unsustainable and detrimental to the economy.

Thanks for great acricle.

Property in Pakistan is overvalued. It needs correction around 40 – 50 % for high end properties.

Thanks for the great article.

Real Estate in Pakistan is overvalued. It needs correction around 40 – 50 % for high-end properties.

Regards

Ali

Property buying and getting profit is without doing any work. But for stock you have to work. You have to keep eye on stock and it needs study too. Keeping in mind our education rate property is better.

The thoughts and the reason that you have shared here are quiet relevant, the graphs and charts that you have shown are up to the mark. My stance is that the amnesty scheme is also one the reason the investor of Pakistan are showing their interest and injecting their money. What do you say