There is a big revolution is underway in Pakistan’s healthcare sector, one that is about to dramatically change not just the sector, but its relative size in the economy. How, and how much, Pakistanis use the country’s healthcare system, and who pays for it, are all about to change. And many parts of the sclerotic healthcare sector are about to feel the effects of that shake-up, not least of which is the pharmaceutical sector, which – by Profit’s estimates – accounts for nearly two-thirds of healthcare spending in Pakistan.

Perhaps we should clarify: it is not one, but two simultaneous revolutions taking place in the country’s healthcare sector, one driven by a rare government policy success in expanding access to healthcare insurance to the nation’s low-income population, and the other driven by the advent of technology and venture capital-backed startups seeking to improve supply chain efficiency in the healthcare space.

The first is driven by the government’s Sehat Insaf program, which provides for health insurance – paid for by the government, but serviced by private insurance companies – to a large swath of the country’s low-income population. The second is the advent of online pharmacies such as Dawaai, which are seeking to remove the inefficiencies and encumbrances of the retail supply chain for pharmaceutical products in Pakistan.

Each of these attacks a different segment of the healthcare sector in Pakistan. The first reshapes how healthcare is paid for, and specifically who can afford what kinds of healthcare in Pakistan. The second tries to improve the buying experience – and possibly even the price points – paid by consumers in their single biggest category of healthcare spending.

Both of these are likely to result in more equitable access and a more affordable, better quality of healthcare available to a much larger proportion of the population. But these changes will also affect the current incumbents in the sector in terms of how they do business. Who will benefit, and who might lose out, is the subject of this story.

Sehat Insaf: improving access to healthcare

The Sehat Insaf program is perhaps one of the biggest policy successes of the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI) government from back when it first took office in the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa provincial government in 2013, and is now being extended nationwide after the PTI took office at the federal level in 2018.

Here is how the Sehat Insaf program works: for low-income Pakistanis – as identified in a variety of government surveys to document poverty and income levels – the government of Pakistan will provide a health insurance plan. But first, a brief primer of how health insurance works in providing access to services in both Pakistan and in other countries.

Fundamentally, insurance is a means of spreading the risks of low-probability events. For an average person – particularly a young person – the odds of getting sick enough to need expensive healthcare is relatively low, but if that happens, the cost is high. So the way insurance works is to take the probability of any single individual needing expensive healthcare costs and multiplying it by the expected expense.

That expense – after adding administration costs and insurance company profit margins – is charged as a premium to people who enroll in the healthcare plan. Essentially, your premium is approximately equal to the probability-adjusted cost of you getting sick and needing expensive care.

The health insurance company then creates a network of providers – hospitals, diagnostic laboratories, doctor’s offices, etc. – that will accept that insurance as a form of payment. If you need care, you go to the provider in the insurance company’s network and they will ask you to pay cash for a small portion of the actual cost, and the rest will be covered by the insurance plan.

The health insurance plan will include how much you will be expected to contribute each month in premiums, how much you will have to pay in cash at a healthcare provider, and total coverage limits on how much the health insurance company will help you pay for.

In a private sector health insurance plan, the monthly premiums are paid for by either the individual seeking insurance, or perhaps by their employer as a benefit offered for employment. In the Sehat Insaf program, the premiums are paid for by the government, so that the person with low income can afford access to the same health insurance that people with well-paying middle class jobs have access to.

What both have in common is a coverage limit: the total amount of money per year that the insurance plan will pay to cover expenses. The Sehat Insaf program will cover up Rs600,000 per year per family (Rs300,000 defined as ‘initial coverage’ and another Rs300,000 as ‘additional coverage’) for high-cost hospital procedures, and up to Rs120,000 per family per year for other types of hospital-based healthcare coverage.

These amounts may not be sufficient for the most expensive hospitals or the most expensive diseases, but they are a lot more money than what most low-income people currently have access to. And instead of begging their employers for help, they now have access to a government program that gives them similar access to healthcare services.

With this card, the labourer working on building a skyscraper has access to the same hospitals and a similar level of services as the mid-level banker walking into that building to work.

While this program has not yet spread nationwide, it already covers an estimated 7 million families, according to the federal health ministry, or about 21% of all households in Pakistan.

The program, as you may have noticed, is not modeled after the kind of healthcare coverage programs found in Europe or Canada. Instead, it is closer in design to the Managed Medicaid program in the United States, where the state governments – with the financial assistance of the US federal government – pay the premiums on health insurance plans for low income individuals and families.

In Pakistan, the structure is almost identical: the provincial governments generally run the program, with financial and technical assistance from the federal government, which also sets basic standards for the program and what it is supposed to cover. The actual insurance is administered by private sector – and government-owned – insurance companies, with the government paying the premiums.

Why expanding insurance coverage matters

Why is this relevant? Because in Pakistan, the vast majority of healthcare costs are paid for out-of-pocket by private individuals. Yes, the government maintains public sector hospitals that provide free or very low cost healthcare to anyone, but those facilities tend to be overcrowded – and their staff underpaid and overworked – resulting in a poor quality of care offered.

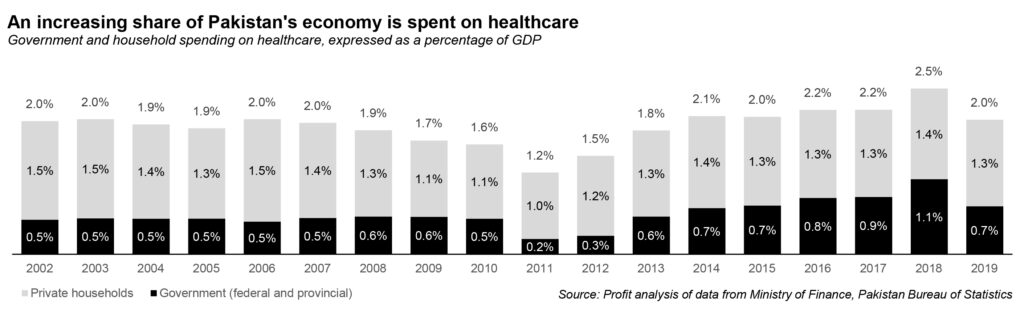

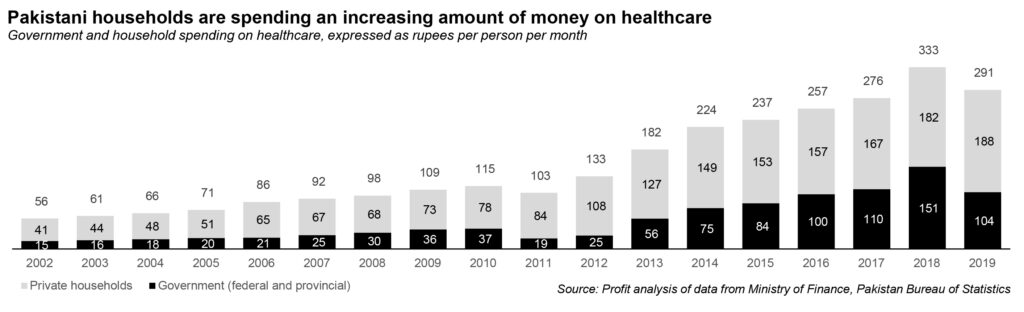

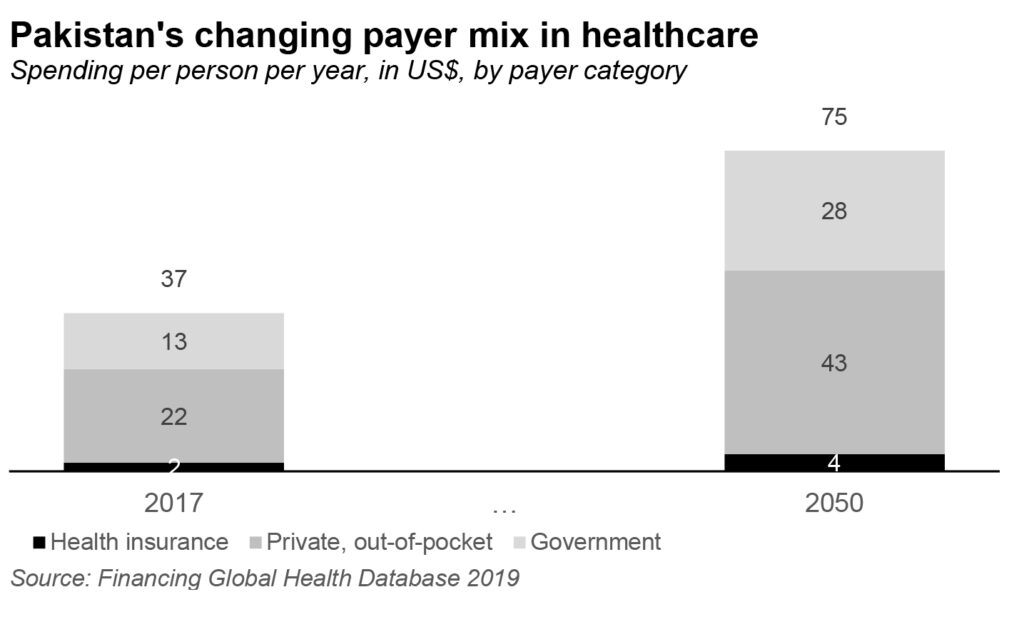

According to Profit’s analysis of data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) and the federal finance ministry, the federal and provincial governments’ combined spending on healthcare accounted for about 35.7% of total spending on healthcare in Pakistan in fiscal year 2019. When it comes to healthcare spending, most Pakistani know that they are on their own, with not much assistance coming from the government.

And while most of the government’s spending on healthcare does go to the poor (mostly because anyone who can afford private sector healthcare prefers that over the public sector), the quality differential between what low-income families can afford, and what middle class and upper income people can afford is tremendous.

By providing health insurance to the bottom 21% of families (a number that may rise as the program expands), the government is achieving two policy goals: improving access to quality private sector care to those who are currently locked out of it by price, while at the same time reducing overcrowding (and therefore, potentially improving quality) at the public sector healthcare facilities.

What does this mean for the healthcare sector? Well, if you are the owner or operator of any type of healthcare facility – hospitals, health clinics, diagnostic laboratories – all of a sudden, about 21% of the population that previously could not afford your services now have the ability to afford them. That is an expansion of your market that is only likely to grow as the Sehat Insaf program expands nationwide.

More people who can afford these services means more revenue for all sorts of healthcare providers, though the biggest benefit is likely to go to hospitals, since the largest number of services covered are those provided by hospitals.

The pharmaceutical sector is not a direct beneficiary of the program, since it does not cover drugs through the insurance plans. But hospitals themselves are users of diagnostic laboratories, pharmaceutical drugs, etc., which implies that the market for even these segments of the healthcare sector are likely to grow. In addition, any money not spent on hospital expenses is money available for other healthcare expenses too, a point made by Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa finance minister Taimur Jhagra.

“An indirect benefit to the pharmaceutical industry could be that despite the fact that the cards do not cover drugs purchased for out-patients, the mere fact that individuals would be able to access healthcare and free treatment, they would be more likely to use the money they saved on buying the drugs they need,” said the minister, in an interview with Profit.

In short, this change is likely to be a positive for just about every single participant in the healthcare sector, and likely every segment of the pharmaceutical supply chain.

The other change taking place, however, is likely to create some winners and losers out of the existing industry’s incumbents. And that is because it is driven by the rise of disruptive, tech-enabled companies.

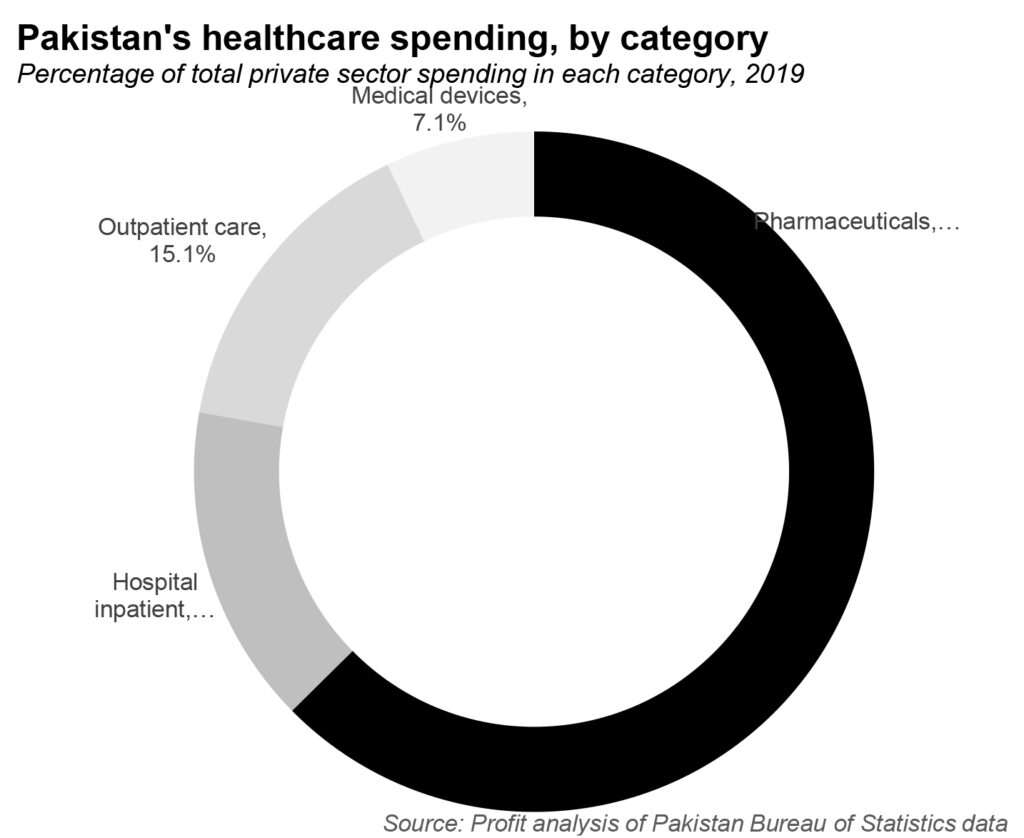

The rise of the online pharmacy

Knowing as we do that pharmaceutical drugs account for approximately 62% of total healthcare spending in Pakistan, based on Profit’s analysis of PBS data, if one had to go about tackling a major challenge in the healthcare sector, it would by definition involve pharmaceuticals. And given the government’s tight regulations of pharmaceutical prices, the way to squeeze efficiencies out of the system would be – as with just about any retail-facing industry in Pakistan – would be to attack the supply chain.

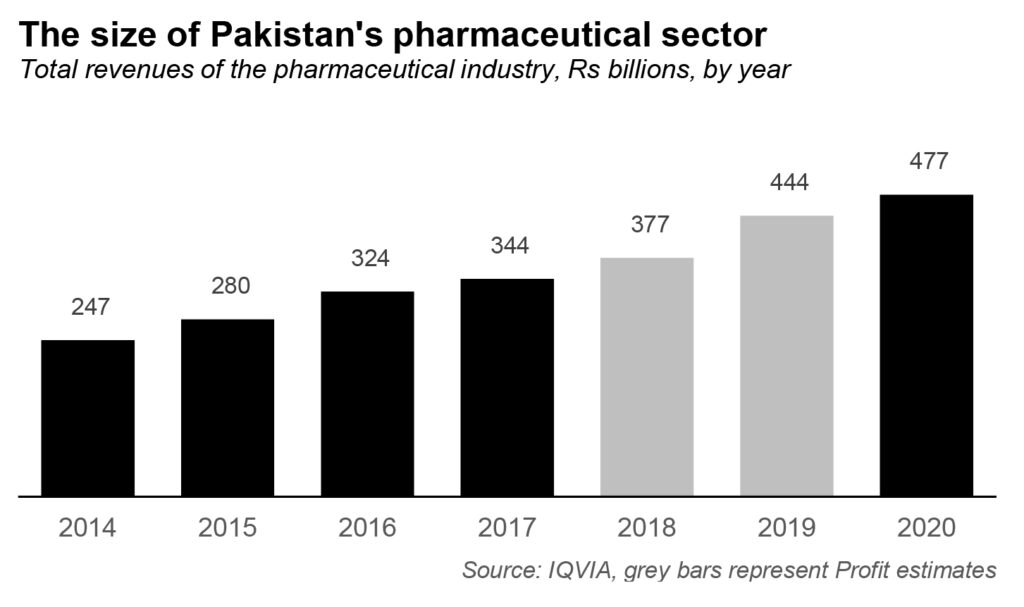

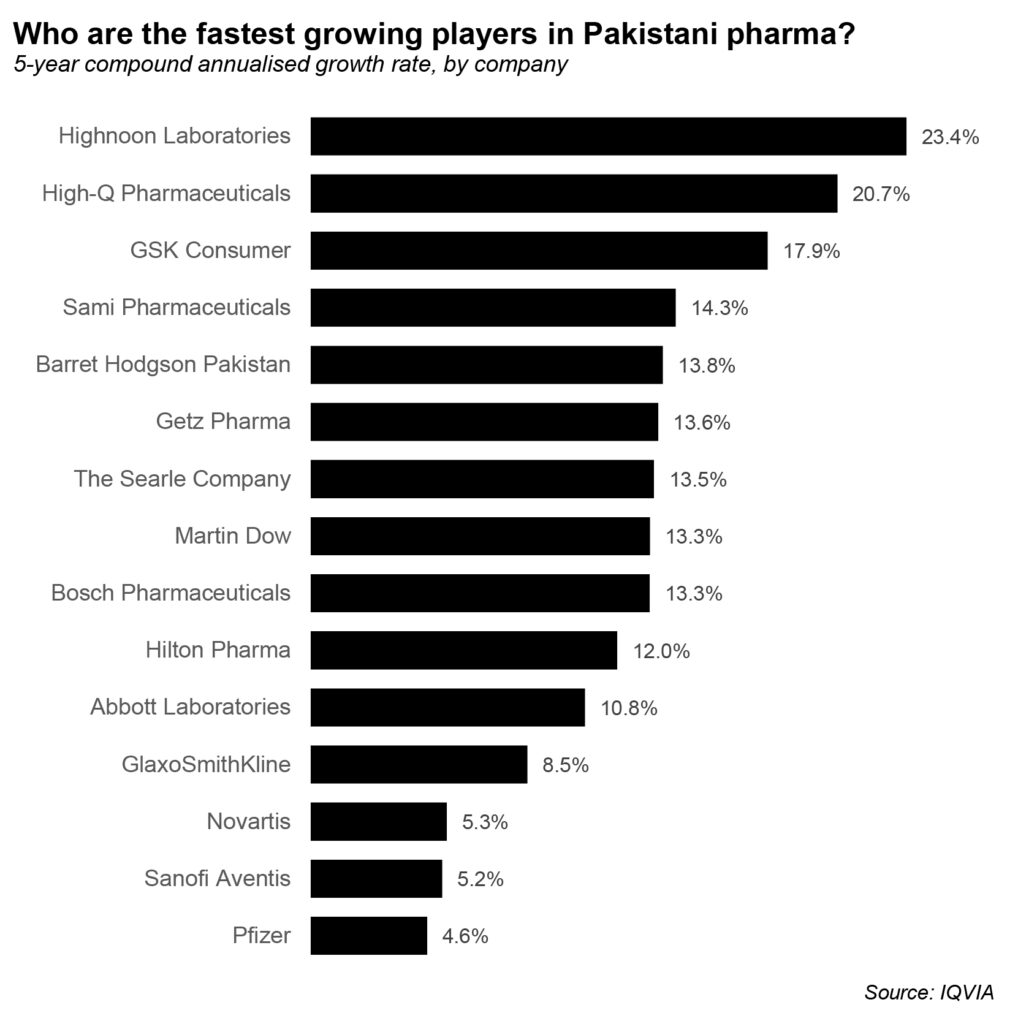

That is the theory behind the rise of online pharmacies like Dawaai, the venture-backed company founded by former derivatives trader Furquan Kidwai in 2014. Dawaai is seeking to disrupt the Pakistani pharmaceutical industry estimated to be worth Rs477 billion as of 2020, according to data compiled by global healthcare data analytics company IQVIA.

Here is why Kidwai believes he has the ability to take market share, and it is not just because he is selling pharmaceutical products online. The entire pharmaceutical industry in Pakistan is regulated by the government under a legislative framework first created by the 1966 Drug Act, which also created the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP).

DRAP has introduced pricing policies first in 2015 and then in 2018 that were designed to ensure that pharmaceutical companies are able to continue to make profits on their products while also not increasing the prices too much for the public. Coming as it did after a 15-year effective moratorium on drug price increases, that change was considered welcome by the industry.

But the structural problem is this: the government sets both the retail price as well as the retailers’ margins, which effectively means that gross profit margins for the entire industry are set by regulatory fiat. The manufacturer is able to receive a price between 20% and 25% below the retail price, which means that the entire supply chain operates on margins contained in that 25% margin.

Of that 20-25% margin, an almost fixed 15% is taken up by the retail sector, with distributors and wholesalers splitting the remaining 5-10%. About 1-3% of that goes to wholesalers, and the rest is taken up by distributors.

Wholesalers, in Furquan’s view, are the source of much of the industry’s problems. “That margin is just not enough… I suspect the wholesale stage of the supply chain is where counterfeiters are entering the market,” said Furquan, in an interview with Profit.

If Dawaai was able to gain enough volumes to become big enough to deal directly with manufacturers and distributors, and then sell the product directly to consumers, it would be able to cut out the retailers and wholesalers in the supply chain, creating a 15-18% gross margin for itself to begin with, and one that could grow as it continued to disintermediate even the distributors.

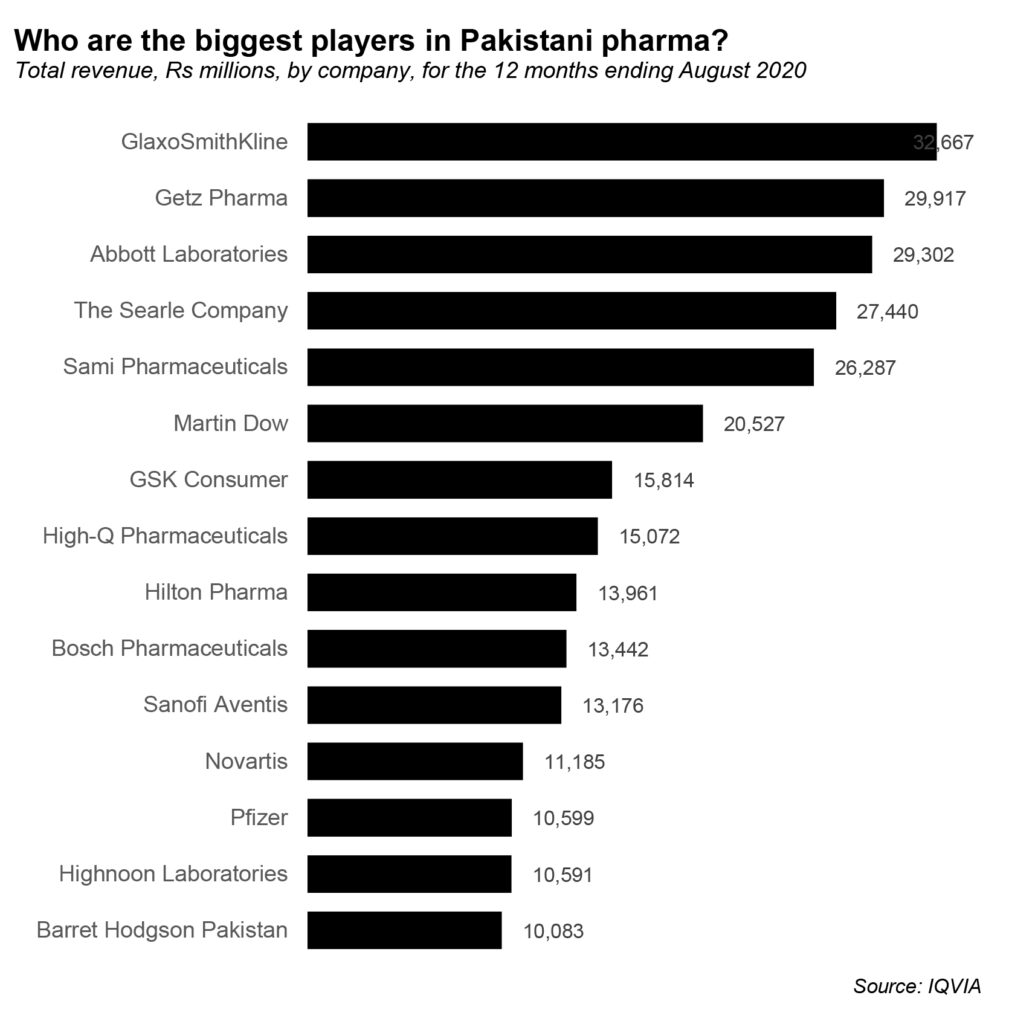

While Dawaai was not willing to disclose details about their financials, sources familiar with the matter say that the company is growing at a rapid clip, and already commands a sizeable proportion of the market. That growth means that it is able to go to more and more manufacturers directly, a process that seems daunting when one considers the fact that there are 775 pharmaceutical manufacturers in the country.

However, of those, the top 15 have an approximately 59% combined market share and the top 100 command close to a 97% share of the total revenue of the industry, meaning the challenge of ensuring an adequately supplied online pharmacy is a little less demanding than it looks at first glance.

Dawaai currently has six warehouses, all of which are rented, in four cities across Pakistan: Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad, and Multan. The company relies on a combination of third-party courier services as well as its own riders to provide its services.

The company’s supply chain is finally beginning to catch up with its own growth: during its hypergrowth phase in 2018 and 2019, several customers of Dawaai complained that they were not able to get their medicines at the promised delivery date. That was because the volume of orders at Dawaai had increased so much that it had trouble keeping pace. According to Furquan, that problem appears to be resolved as its distribution infrastructure is now able to keep growing with its order flow.

How online pharmacies can shake up the market

How does this matter to consumers? If Dawaai is able to cut out two to three layers of middlemen, it can offer more competitive prices to consumers while at the same time guaranteeing quality in a way that most small retailers cannot. Prices are already low in Pakistan, so affordability is unlikely to increase much given the limited room Dawaai has to cut prices, but eliminating counterfeits from the supply chain is likely to improve healthcare outcomes, particularly for low-income segments of the population, who are more likely to not have access to the larger retailers that offer a more reliable quality of drugs.

This is an especially important point: the development of pharmaceutical drugs takes place largely in the United States, a healthcare system that is so hospital-heavy that the focus on drug development has been on trying to treat using drugs some conditions that currently require physician or surgical procedures. The most common example of this is stomach ulcers, which used to require major surgery to treat, but can now be treated with pharmaceutical drugs.

Improving access to high-quality drugs – at or below current retail prices – will likely be result in a significant improvement in health outcomes for Pakistanis who are most vulnerable to being the victims of counterfeit medication fraud. And it will come at a time when Pakistan’s pharmaceutical sector is increasingly part of the larger global pharmaceutical supply chain.

For instance, in 2014, Gilead Sciences – the US-based pharmaceutical giant – announced a partnership with Ferozsons Laboratories for the manufacturing of Sovaldi and Harvoni, two drugs that can cure hepatitis C, a disease that was previously thought of as a chronic condition that could only be managed, but not cured. And Pakistan is now part of the global drug trial network for the Covid-19 vaccines being developed by pharmaceutical companies based in other parts of the world.

Rare, expensive drugs, in other words, are becoming increasingly available at (relatively) affordable prices to Pakistani consumers, if the adequate safety and anti-counterfeiting measures are taken. An online pharmacy that can disintermediate the most vulnerable portions of the supply chain – the wholesalers – can help expand access to that world of therapies.

If, on the other hand, you are a retailer, wholesaler, or even distributor of pharmaceutical products, you would likely look at Dawaai as a competitive threat. After all, Dawaai’s view is that these intermediary layers serve only to increase the price that consumers end up paying, mainly the cost of an inefficient supply chain that has not been developed by anyone currently making money off of it.

And Dawaai’s success at disintermediating those layers of middlemen has in turn already inspired the launch of other online pharmacies, the most recent of which is MedznMore, which includes as its cofounders a former Dawaai employee and raised $2.6 million from anonymous investors just this month to start operations. (The company is too new for us to analyse it in any detail yet.)

The larger retailers are likely to be fine for a while. According to one source familiar with the matter, Imtiaz Supermarket, one of the largest retail chains in Karachi, sells as much as $10 million a month in pharmaceutical products from just one of its flagship stores. Over time, however, Dawaai is likely to become a competitive threat to anyone in the pharmaceutical supply chain.

“Given the knowledge that has been built up by Furquan and the resilience he has demonstrated, we think they can become one of the largest pharma movers in the country,” said Rabeel Warraich, founder at Sarmayacar Ventures, which led the last round of investment into Dawaai. “It could even be taken beyond Pakistan, though of course Pakistan is a large enough market to build a very valuable business.”

In order to be successful, however, Dawaai will have to ensure that it invests in developing a better infrastructure than its competitors, a strategic imperative that might be in conflict with the company’s current ‘asset-light’ business model, which involves rented facilities rather that wholly owned ones.

Pharmaceutical products can often require temperature-controlled supply chains from the factory to the customer’s doorstep, particularly for some high-cost, high-margin products. Pakistan’s cold-chain infrastructure, while improving, is still nowhere near as extensive as it needs to be.

Conclusion

After years of neglect, it appears that Pakistan’s healthcare sector is finally getting the kind of attention it deserves, both from policymakers seeking to improve access, as well as from tech-enabled enterprises seeking to improve efficiency and outcomes. The net result is likely to be a healthier population and a healthcare system that delivers better outcomes at a lower cost.

all data of this website are very useful beacuse in corona pandimic every one use madicnes we also know best comapnay vision pharma

very useful information in this website all content are very important we also know best website for pharmaceuticals at unichemPakistan so visit our site and see latest information about

Imtiaz selling 10 million dollars worth of meds a month must be typing error. No?