Big business in Pakistan is excited. The government has provided various stimuli and planning wheels are in motion to invest and expand in sectors like real estate, steel, cement and textiles. Wonderful? Perhaps. Shortsighted? More likely. Why? Because there’s a feeling of déjà vu to this scenario. Been there, done that.

How many times have we seen cycles of boom and bust come and go over the past few decades?

GDP growth rates remained relatively high under the last PML (N) government while exports touched their peak in the PPP regime before that. And remember the Musharraf heyday? Pakistani businesses never had it better, with stock markets rising to unprecedented highs.

What’s common in all these booms is the combination of amnesty schemes and cheap credit coupled with industry-specific concessions to the most influential.

Each time the country goes through this cycle, the disparity between the rich and the poor increases further. This leads to a greater concentration of wealth and private power and a disaffected and declining middle class.

Concentrated economic power in the hands of the few, state or private, is a recipe for disaster for most of the population. It has much wider implications than the economic fallout.

“If we learned one thing from the last century, it should have been this: the road to fascism and dictatorship is paved with failures of economic policy to serve the needs of the broader public”, writes Columbia law professor Tim Wu in his book titled ‘The curse of bigness’ published in 2018. He goes on to add in the book;

“Gross inequality and material suffering feed a dangerous appetite for nationalistic and extremist leadership”.

Clearly, he is referring to the experience of the western world with the advent of Nazism and its resulting horrors but the observation holds true in the current scenario too, in nations around the world. Closer to home, we see leaders in our region pandering to or whipping up “religious” extremism for political agendas, to shore up their own regimes.

What does this have to do with the economy? For one thing, it is clear that like many countries, Pakistan has long followed the American model, accepting the Chicago school’s trickle-down laissez-faire economic theory as best suited to this economy. The difference is that the State continues to use its power to influence and support vested interests whenever expedient and does so more frequently and thus has bigger impact relative to the size of the economy.

Take the power sector. The only reform the government is willing to consider is to privatize certain state-owned entities. I am not against privatization, indeed it can result in some improvement, but to carry out privatization while leaving the privatized entity’s respective monopoly intact makes zero sense.

What successive governments don’t seem to understand – or if they understand they choose to ignore it – is the simple fact that it is monopoly power, not ownership, which is the root cause of what ails the power sector.

There may be some instances where monopolies have acted in the interests of the general public, but these are exceptions rather than the rule. It is the government’s job to regulate and to create competitive markets that allow anyone to invest and manage. Whoever does a better job of this is welcome to make all the money they want, as long as they do it fairly, beating competition in terms of service delivery and price.

Privatization implies that there will be competition. But that is not the kind of privatization we have seen in Pakistan power sector, where public sector monopoly rights are transferred to the private sector, leaving little incentive to improve.

Understandably, it is difficult to create competitive markets in certain sectors particularly where the infrastructure needs to be built and shared. However, most of the developed world, and many developing nations, including India which started with similar economic model as us, have overcome this problem. There is no reason why Pakistan cannot do the same.

It may not be common knowledge that the major areas of reform in the western world post-World War Two included the anti-monopoly and competition laws which emerged in the 50’s and 60’s. The US Justice Department has famously waged war against monopolies in diverse sectors from banking to grocery stores to shoe producers. It even pursued technology and telecom giants IBM and AT&T which were forced to break up after years of litigation. Likewise, Europe insisted on the breakup of large German companies and The UK took similar steps.

These reforms helped reduce the share of top earning individuals and companies in overall national incomes with growth and prosperity being broad based as a result thereof.

While advent of neoliberalism over the last two decades may have reduced anti-monopoly enforcement, the anti-monopoly thinking is fairly well embedded in the practiced capitalist model. It is therefore not surprising to see US and EU regulators once again moving to break up monopolies like the current technology giants Facebook and Google.

Why do nations that are the pillars of capitalism try to smash monopolies and cartels? If the system was best left alone and allowed to continue no matter the size of the corporation, why do governments consistently try to undo the largest ones? The answer lies in a fundamental belief entrenched in these countries about the potential damage caused by unrestrained private power.

Without such a belief, no amount of legislation or creation of competition commissions will address the issue.

In Pakistan, the Competition Act 2010 mandates the Competition Commission of Pakistan to control monopoly abuse. But the Commission has no real power, no teeth to back it up and successive governments have denied the Commission appropriate financial support.

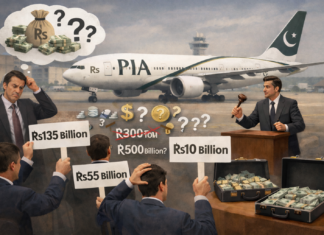

The biggest success against monopolies in Pakistan has been in the telecom sector, mainly driven by the arrival of a disruptive technology — mobile phones. There have been small victories in banking and airlines but nothing much else of note.

Unfortunately, Pakistan has suffered from a lack of meaningful reforms for decades. The reason it cannot sustain any sort of economic improvement is because those so-called periodic improvements have no real deep rooted economic case. They are short-term measures aimed at meeting short-term goals. What Pakistan desperately needs is long-term vision and deep structural reforms. Not the type which win talk show contests.

Curbing monopoly power cannot be a short-term goal. And so it continues to strangulate Pakistan’s economy, preventing it from fulfilling its potential.

Spot on !!

A test case to review the Digitisation in Pakistan of telecom networks. This means the networks media, which is the OFC Optical FiberCable will transport the bandwidth of the internet from your home through out the SEAMEWE network. The whole country has Digitalised with the exception of PTCL ISP which provides internet services. There is an urgent need to consider the Digitisation of PTCL networks to the UN/ITU reccomendations for Digitisation particularly in Karachi. The whole city is analog. Please consider..

Good article