“If ye give thanks, I will give you more (Holy Quran)”

The above quotation from scripture is what a recent report for the nine month period of 2021 for Dewan Cement, recently released to the PSX on April 30 started. We mention it because of a crucial fact: Dewan Cement is part of an industry that perhaps unlike any other, was ‘given more’ in the year of the pandemic.

When things go wrong and times are tough, such as they were and continue to be because of the global pandemic, all industries in Pakistan like to complain and ask the government for handouts and tax breaks. One of the industries that the government actually listened to was the construction sector, particularly because they wanted to keep it running so daily wage earning labourers would not be put out of work. As a result, to recap, the cement sector picked up significantly in 2020. First, the interest rate was cut significantly by 625 basis points to 7%, helping with loan repricing, and new loans for large projects.

Second, the federal government announced a construction package in April 2020, upon which investors will also be granted a waiver of up to 90% on tax, if they are investing in construction projects under the Naya Pakistan Housing Scheme. The government also followed up with more incentives for the industry in the new budget for fiscal year 2021. Around Rs69 billion was allocated for dams, and Rs30 billion was allocated for the Naya Pakistan Housing Scheme.

Third, the central bank asked commercial banks to allocate 5% of their total lending to the construction sector (banks’ current exposure to the sector is only at 1% of overall advances). This was provided at a low rate of 5% and 7% for five and 10-marla houses (one marla is around 225 square feet).

This meant – that as Dewan Cement’s own report mentioned – the cement industry has had a yearly growth of 17%. Local dispatches volume stood at 43 million tons compared to 37 million tons in the same period last year. The overall sales volume increased by 6 million tons, with local sales growing 18% to 36 million tons, while export sales increased to 10.87%.

And guess what did not grow? Dewan Cement.

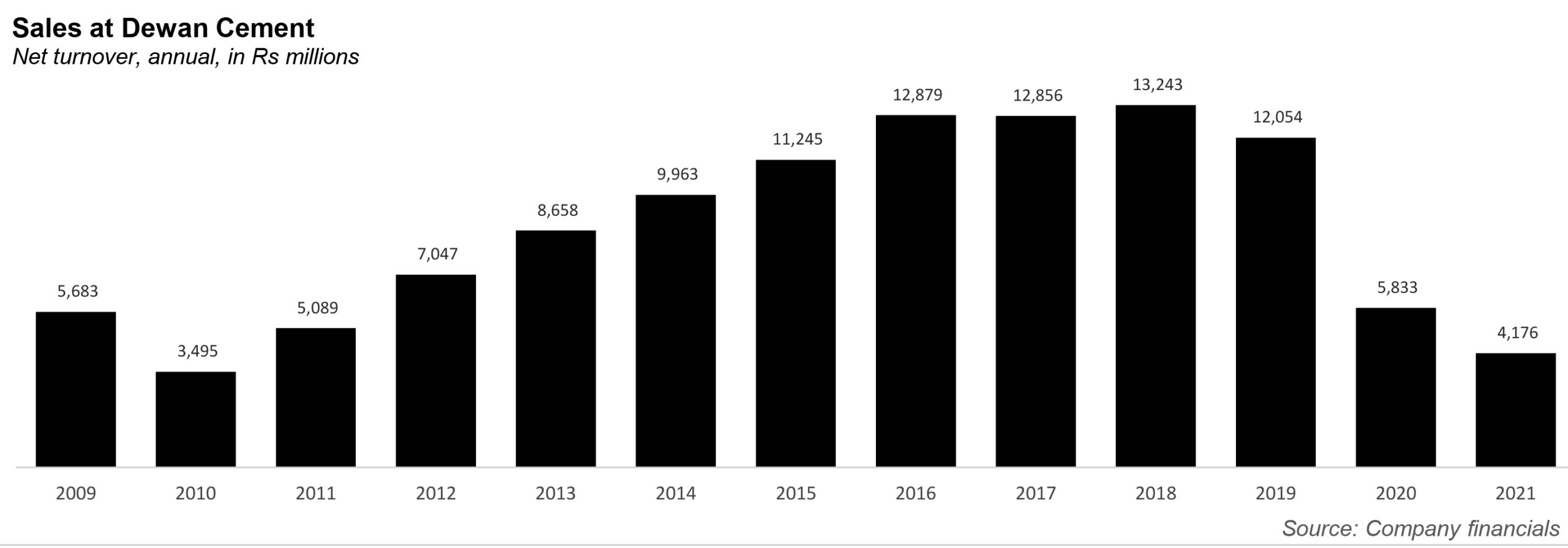

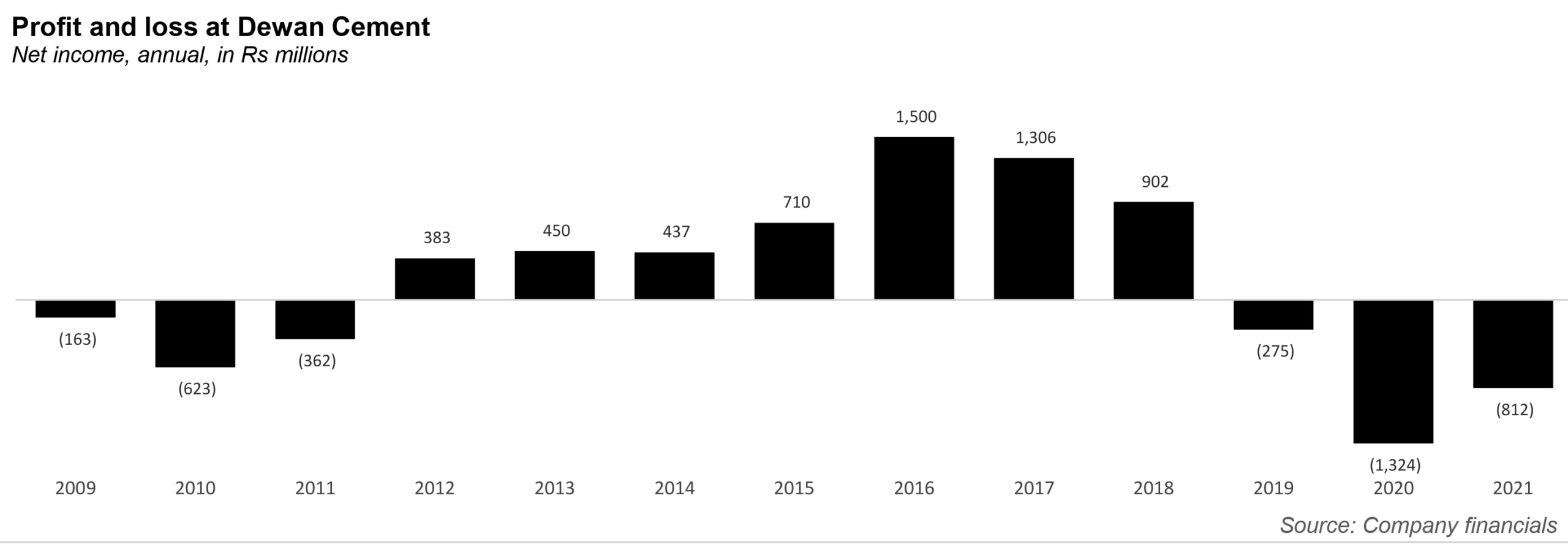

Somehow, in the greatest year to ever bless the cement industry, Dewan Cement’s two plants remained essentially shut (the company has two production facilities at Deh Dhando, Karachi, and Kamilpur Hattar Industrial Estate, in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa). The company performed poorly in both 2020, and 2021. In 2020, the company made a loss of Rs1,324 million – an astonishing figure, even when compared to the loss the company the year before (of Rs275 million). It also made the lowest revenue figure since (at Rs5,833 million), since 2011 (where it stood at Rs5,089 million).

And the year 2021 is also not looking great either. For the nine month period ending March 31, 2021, the company’s revenue stood at Rs3,744 million, compared to the Rs5,401 million just the year prior. The company’s net loss fared slightly better, standing at Rs226 million, compared to the loss of Rs738 million the year prior. If one analyzes the data, the company’s net revenue is set to stand at Rs4,176 million, comparable to 2008-2010 era figures, erasing any of the gains of the last decade. And the annualized net loss stands at Rs812 million – the second highest loss since 2009.

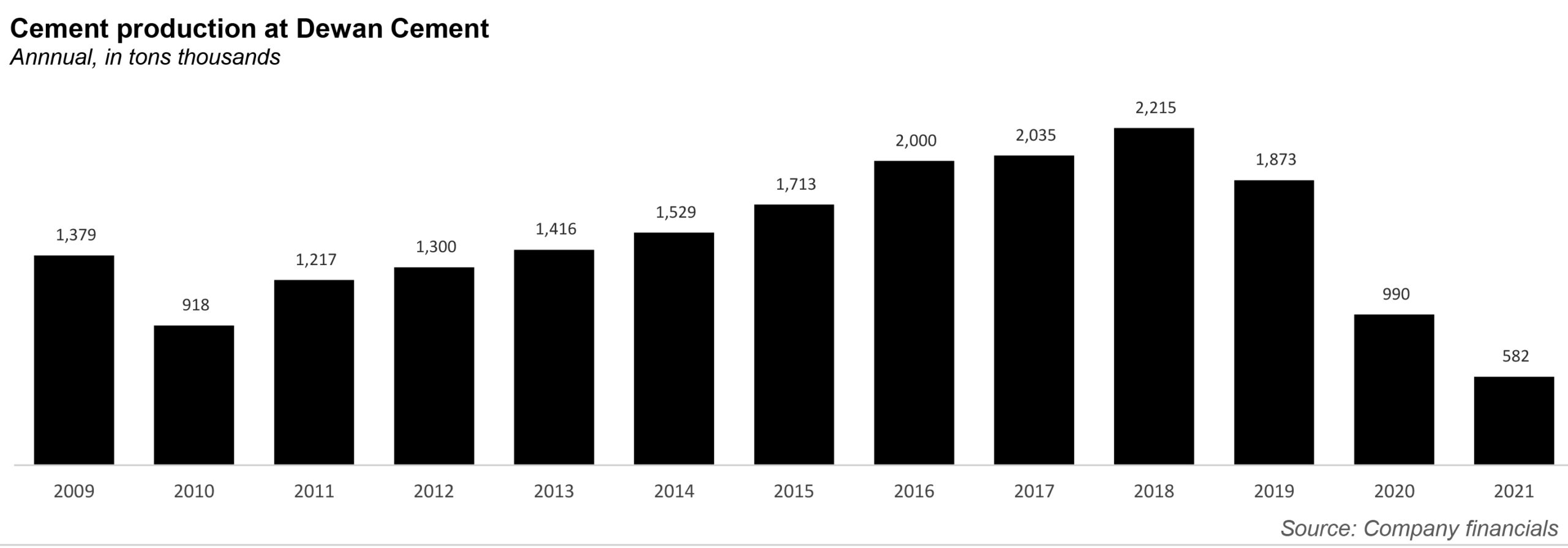

And here is the real kicker: in a year where cement companies were producing more cement than ever before, when (as Profit has previously covered) competitors are opening up new cement plants, Dewan Cement produced less cement than ever before. At its peak, it produced 2.2 million tons of cement in 2018: this figure dropped to 990,000 tons in 2020, and is set to settle at 582,000 tons in 2021.

What gives?

To understand what is wrong with Dewan Cement, and why its cement plants are lying around quite uselessly, it helps to have a little understanding of what is wrong with the Yousuf Dewan Group itself.

A quick history recap: the Yousuf Dewan Group started in 1912, as a small company dealing in used garments. The group grew steadily over the century. Then, in the late 1990s, Dewan Muhammad Yousuf Farooqui started to play a more active role. In the 2000s, he leveraged his friendship with then President Musharraf to expand the group, which would hurt him in 2008, when the arrival of the Pakistan’s People’s Party meant the group would no longer get special attention. It did not help that that was laos the year when a global financial meltdown hit the cash flows of the conglomerate badly. Most of its businesses depended heavily on imported raw materials, like auto kits, coal and polyester. Banks revoked credit lines, and the group’s companies were left without working capital to run even everyday operations.

The Dewan empire crumbled like a house of cards: from posting a net profit of $5.8 million in 2006, the group went on to register the country’s largest-ever default in 2008. Sources put the default at close to Rs55 billion.

The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) forced banks to set up the steering committee to help minimise the loss arising out of the country’s largest default. And because the banks decided to go pari-passu (or an arrangement under which all creditors are regarded equally and repaid at the same time and at the same fractional amount as all other creditors), the Yousuf Dewan Group was given a second lifeline. Then in 2015, the steering committee came up with a debt restructuring plan in August 2015, which was then mysteriously shelved. Instead, the committee wanted the group to sell their cement business.

Previously, Farooqui had shown some willingness to sell his cement plant around 2012, but found the price at the time (Rs7 billion according to sources) too low. And something else happened in the meantime: the company began to do well (as the numbers show) and by 2018, could fetch up to Rs20 billion. Please, for the love of God, sell, said the banks.

And from the banks’ perspective, it makes sense. Sell the most profitable asset you have, and you can prop up the rest of the defaulting company. Besides, in the latter half of the 2010s, even before the recent cement wave, existing groups were clamouring to buy up cement plants. According to Shankar Talreja, deputy head of research at Topline Securities, the cost of setting up a new cement plant is so astronomically high, and the amount of capital required to get it running, that groups find it much easier to buy existing plants and revamp them, thereby providing an easy in into the market. By his own estimates, there are anywhere around 15 groups at any given time trying to enter this lucrative business, and be potential buyers. Think of how the Bestway Group, by way of example, bought a non-operational plant in 2005, and another in 2015.

But where are the buyers?

Avoiding the Yousuf Dewan group, at all costs.

According to Talreja, the excessive legal constraints have ruined Yousuf Dewan’s group image. And that matters. We at Profit have previously covered the impact of multiple defaulters walking around scot-free in Pakistan, running circles around banks. But, apparently, there are standards even within the defaulters.

As the financial information for the period ended 31 March 2021 shows, the company’s current liabilities exceed its current assets by Rs3,553 million. As the company itself notes, its short-term borrowing facilities have expired, and it has been unable to ensure scheduled payments of long term borrowings due to the liquidity problems. Most of the lenders have gone into litigation.

And that is why, it seems, no one wants to touch Dewan Cement with a 10-feet pole. No buyer wants to be dragged into the Yousuf Dewan saga – and it has been a decade long saga, which adds to that image problem.

Part of that image problem of the man himself. Some, according to sources, won’t do business with him out of political leanings. After all, the man was closely linked to Musharraf, a former president who is practically irrelevant to politics today, and is not on the best terms with the PPP – a political party that can command outsize say in certain industries, particularly in the province of Sindh.

Yet others say that the problem is less dramatic, and in actuality it is Dewan’s own hesitation that has cost him. Time and time again, since 2008, in 2012, and again in 2018, offers have been made to the Dewan group to take this asset off his hands. But Dewan himself created a reputation of not accepting past offers. Now, when the time is dire, it turns out buyers simply do not want to waste time on a company that will barely sell. In fact, the group faces a serious credibility crisis as it turns down offers for its cement plants for the umpteenth time, raising doubts about its intent to sell and settle the default.

Yet another theory abounds: that in fact, Dewan Cement is underreporting its revenue and profitability numbers, and in fact, is doing well, just like the other cement players. Others say this theory is entirely a myth, as the fact of the matter is the plants are shut, and figures can not be manipulated to that extent. But the prevalence of such a strong rumor explains why several potential buyers are thrown off by the ‘shady’ image of Yousuf Dewan.

Concern about the numbers could easily be averted with a robust audit. But the group’s books are not audited by one of the big four firms – Deloitte, Ernst and Young, KPMG, and PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). Instead, the group’s auditors are Faruq Ali & Co Chartered Accountants. Now, the auditing company is an old one, having been set up in 1967 by a chartered accountant. And, many companies in Pakistan use local audit companies – perfectly fine to do so. However, a group the size of the Dewan Group, and facing such a serious credibility problem – to not be able to get one of the more recognized audit firms to audit its books, has led to, again, questions about the Dewan Group’s real intent.

And having a recognized audit firm matters. The Big Four are trusted more than other firms, and by more investors, which means that they get to command a higher fee than other firms (in some cases, commanding prices that are four times higher than the number five firm). The Big Four can charge higher prices because there are people willing to pay more for the ability to say that they are subjecting themselves to the rigours of an audit conducted by one of the Big Four firms, which is perceived to be better.

All of this is to say that perception matters, and that Yousuf Dewan has bungled his image in front of buyers. It seems the group will have to do more than just ‘give thanks’ – it will quite literally have to reinvent itself.

Dewan group which became a household name in the past is now hardly talked of. The variety of industries they invested in, their shares are hardly purchased in the KSE100 index. It is sad.

Salams

Yousef Deewan is corrupt and fraud person and do not want to return money which was borrowed from he should be in jail and all his businesses should be auctioned

This group has a history of fleecing public money.. got example Dewan Salman Fibre. Listed in KSE but very shadowy transparency and accountability. Common investors lost but sponsors siphoned money conveniently. So much of poor oversight by regulators.

You didn’t mention:

1. how the bankrupt Dewan “restarted” its operation?

2. who is backing this company?

3. you will not find “Dewans” in the new BoD.

4. Launched new website, like TELE

Pakistan should improve its economy. How can a country with such a large population be so economically unproductive?