The Pakistan Super League (PSL) is perhaps one of the best business decisions that the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) has made in its history. The league provides the board with a steady revenue stream each year, it has reopened the doors of international cricket in Pakistan, and has allowed the PCB to form connections with and sign major deals with international broadcasters.

The PSL is also perhaps one of the worst business decisions some of the franchise owners have made. Over the course of the past 6 years, the PCB has made a neat profit from every edition of the tournament in addition to collecting hefty “franchise fees” from all of the team owners. In comparison, only one or two teams have managed to break even, with the others facing consistent losses.

Stung by the losses, the franchises have for years been complaining about what they claimed was an unfair revenue sharing model – which has finally been changed this year. Under the auspices of the new model, the teams will get 95% of the profits that the tournament makes and the PCB will take the rest of the 5%. In previous years, this model was closer to an 80-20 split so the change is significant. However, because of the high franchise fees and a lack of will in commercializing the franchises better, many of the teams will continue to face losses.

Yet the team owners neither seem to be going anywhere nor are they in any sort of a hurry to put their franchises up for rebidding. A big reason is the screen time that the PSL gets the owners of these leagues. In a country where influence is currency and fame is an asset, team owners like Javed Afridi, Fawad Rana, and Salman Iqbal have become household names through the PSL. Being part of the ‘owners club’ is not just a status symbol, but also a way to influence the league and tap into a large marketing audience.

Profit spoke to Sami Ul Hasan, the media and coms director of the PCB, franchise insiders, and cricket journalist Osman Samiuddin to get insight into how a tournament like the PSL makes money, how much it makes, and the unique set of conditions that have brought the franchises and the PCB to where they are today.

How the PSL makes money

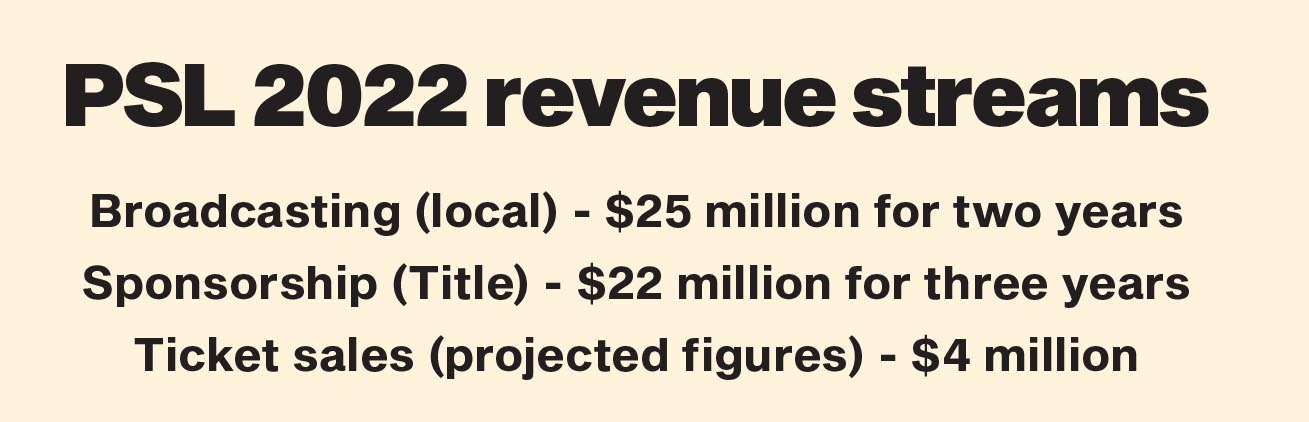

Let’s get some things out of the way. The PSL is worth serious money. Every year the tournament brings home the bacon for the PCB by selling tickets, selling sponsorships, and selling the broadcasting rights to the matches. This year alone, the cricket board sold the local broadcasting rights for the tournament to a consortium of ARY and PTV for the hefty price of $25 million for a two year period. Similarly, the title sponsorship, which has belonged to HBL since the beginning of the tournament, was sold to them again until 2025 for nearly $22.5 million (and this is only the title sponsorship, which means the revenue from other sponsors has not been factored in.) And while the PCB does not have its earnings from this year’s ticket sales, they managed to rake in upwards of $2 million back in 2020.

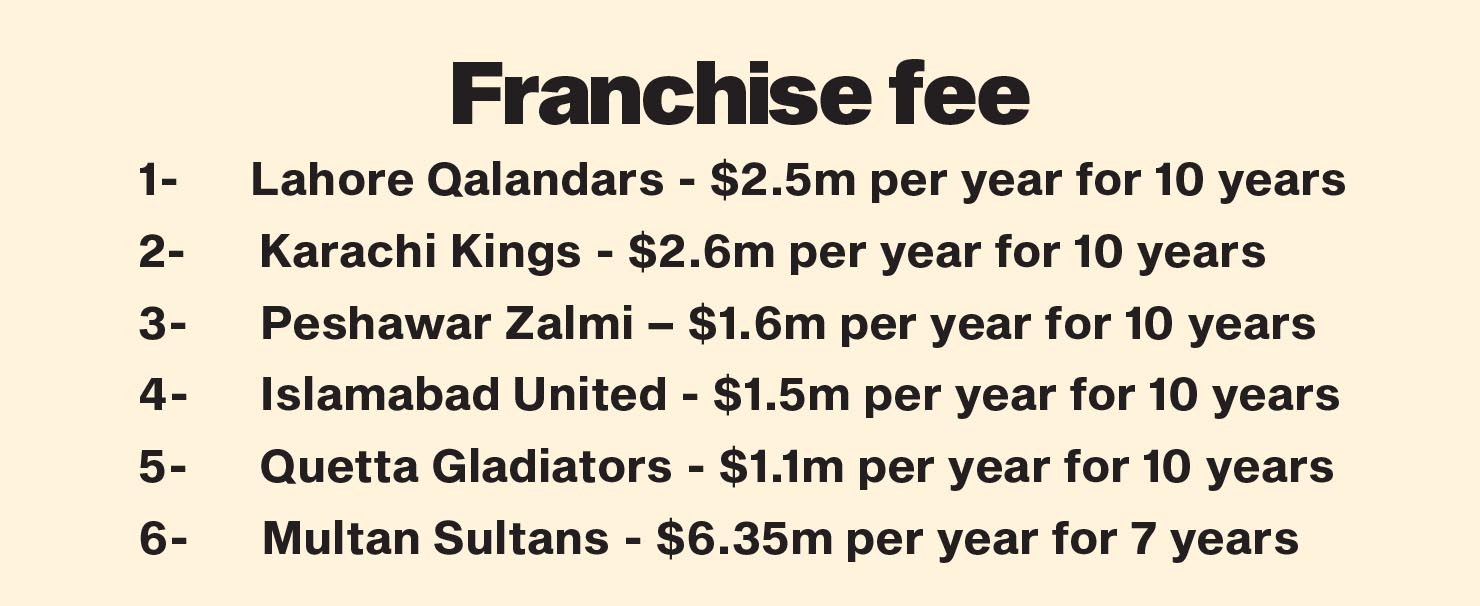

This is how things stand today. The first time that it became apparent that the PSL could be worth the big bucks was back in 2015, when the PCB sold the rights to five franchise teams that would play the tournament for $93 million for a 10 year period. The most expensive team to be sold was Karachi Kings for $26 million, followed by Lahore Qalandars for $25 million, Peshawar Zalmi for $16 million, Islamabad United for $15 million, and the Quetta Gladiators for $11 million. Since the teams were sold for a 10-year period, the total cost was payable over 10 years in the form of a yearly franchise fee equivalent to 10% of the team’s value. Essentially, each franchise owner would rent out the use of the franchise for the year for a fixed price.

The reason Karachi and Lahore were more expensive while Islamabad, Peshawar, and Quetta were cheaper in comparison was because of the sizes of the cities. The idea was that each team would be able to become a ‘brand’ of the corresponding city. As such, brands like Karachi and Lahore would be able to tap into more commercial opportunities and partnerships because they had more money and people in their cities.

Back then, betting on the PSL growing and turning into a successful cricket franchise league was risky. Pakistan was still not regularly hosting international cricket because of security concerns, and the PCB was suggesting hosting the entire league in the UAE to make sure that foreign players would come and play in Pakistan. It was thus a little surprising that the PCB managed to get the amount of money that they did for the franchises. Especially since the franchises would not just pay their franchise fees each year, but also have to spend money on paying players, coaches, and other support staff as well as marketing.

The money was not paid upfront because none of the teams could really afford to pay up like that, and because there was no knowing where the teams would be in 10 years. For that first tournament held in the UAE in 2016, despite all odds, the PSL managed to turn a profit. Back when the teams had first been sold by the PCB, it had been agreed that at least 80 percent of the revenue from the broadcast rights would be split equally among the five PSL franchises. The remaining 20 percent will go to the PCB. Similarly at least 50 percent of the revenue from the sponsorship rights will be shared among the franchises and the PCB will utilise the other 50 percent.

Eventually, when the central revenue pool was calculated, it turned out that the PSL had turned a profit of $2.6 million. Out of this, the PCB pocketed $0.6 million while the rest of the $2 million were divided equally among the five sides – leaving each side with a mere $0.4 million. The sides all ended up making a significant loss in the first year. And how could they expect not to?

In the first edition of the PSL only, the Karachi Kings for example had paid $2.6 million as their franchise fee. This was the same amount as the entirety of the PSL made. Not only did the Karachi Kings only recover $0.6 million of their initial investment for the first year, they also had to spend more on top of that. There is no auction in the PSL unlike the IPL, but instead a players draft where each team can spend up to $1.2 million on buying players for their teams. Money spent on coaches and marketing is seperate. This meant that Karachi alone was spending somewhere around the $5-6 million mark on the first edition of the PSL alone.

The tournament was bringing in more revenue than it was spending money, but the franchise fees were too high for any of the teams to even come close to breaking even. While moving the tournament to Pakistan would bring in more sponsorship revenue as well as reduce costs by no longer needing to rent a venue to play, these changes would not have the sort of impact that would bring these teams out of their losses. The problem was also becoming particularly stark because all of the local owners of the teams in Pakistan were making money in the Pakistani rupee – which was fast plummeting in value – while the PCB demanded that franchise fees be paid in dollars. Effectively this meant that their fixed yearly fee was also rising.

And because some of the teams have larger fees than others, bigger teams like Karachi Kings and Lahore Qalandars were making bigger losses than teams like Quetta and Peshawar, which had significantly smaller yearly fees to pay. This revenue sharing model immediately became a bone of contention and the issue continued over the next few editions of the league.

The financial model struggle heats up

In January 2019, the extent to which the teams were making losses became apparent when the PCB accidentally leaked a document revealing just how much money the teams had lost in the first two editions of the tournament.

Cricinfo reported that the PSL franchises incurred losses ranging from $1.4 million to $5 million each in the first two seasons of the league – leading them to demand financial restructuring of the league as well as tax exemptions from the Pakistan government.

This meant the PCB had some serious egg on their face. The report was leaked because a copy of a letter that was sent by the PCB to the finance minister of Punjab, which includes consolidated financial details of the five franchises from the 2016 and 2017 seasons, was erroneously sent to all franchises, inadvertently revealing the financial details of each franchise to the others, a slip-up that the PCB chairman Ehsan Mani had to apologise for.

The knowledge of the losses suddenly became apparent not just to the public, but also that the teams knew just how deep the others were in it as well. While it was embarrassing in the moment, it also helped all of the owners realise that they could work together towards revising the existing business model. Within a year, in September 2020, all six of the teams banded together and sued the PCB.

“While the Franchisees have been dedicated towards realising the vision and goal of the promotion and development of the sport of cricket and at the same time building a positive image of Pakistan, unfortunately, we have serious reservations with the existing financial arrangement and model of PSL,” the statement said. “PCB has demonstrated an unwillingness to discuss, deliberate or revise the arrangement in a serious manner forcing the hand of the Franchisees time and again…”

The franchises reiterated that the PSL has been profitable for PCB at a time when they were suffering heavy losses.

“Since the inception of the league, the Franchisees have collectively suffered losses in billions of rupees while the PCB has made billions…In light of the losses suffered by us over the past five seasons and PCB’s constant unwillingness to consider our grievances seriously, all six Franchisees have been constrained to approach the Honourable Lahore High Court against PCB…,” the statement added.

Ramiz brings in a new model

Clearly at this point the teams were upset not just because they were making losses, but also because the PCB was making serious profits. Not only did the PCB have the franchise fees coming in every year, they were also taking a sizable chunk from the central revenue pool.

As pressure mounted with the court case the teams also began to dilly dally. They began making payments late, blaming the dividends they got from the league. Karachi and Lahore in particular became serial offenders, and the PCB ended up having to pay a lot of expenses out of pocket that they should have been paying from the money they were getting from the teams. Even when it comes to paying the players, when the PSL draft happens, the PCB pays the players and then collects the money from the franchises later or cuts it from the revenue pool before declaring its final profits.

As the PCB found itself a little weary from carrying the weight, new Chairman Ramiz Raja stepped in. A former cricket player with a stronger resolve than the more meek Ehsan Mani, Raja sat the franchises down. This was the first thing that was different – under the Mani negotiations were done half-heartedly at times not because of the Chairman but because it was not a big priority. Ramiz on the other hand sat the teams down and gave them many of the things they wanted. He also told them to take it or leave it, and reportedly when one of the team owners seemed to be showing some resistance, Ramiz said he would not hesitate to put that franchise up for rebidding if they did not join the PCB and the rest of the teams on the same page.

The first was that the teams would now get a 95 percent share of the central revenue pool rather than the 5% they used to get. As reported by Cricinfo, in the new model, all franchises will get 95% of revenue generated from all revenue streams including broadcasting rights, sponsorship rights and gate receipts from the seventh edition onward. For PSL 5 and 6, the PCB will share 98% of the central pool revenue as an additional relief in view of the Covid-19 pandemic that disrupted both seasons. In previous years, the revenue shared varied between 85% and 90%.

The franchises wanted the PCB to give them rights in perpetuity but that is not part of the new model. As per the original contract franchises will have to pay an increased franchise fee [existing fee + 25% or 25% of market value of the franchise, whichever is higher].

The most important concession, however, has been that the price of the dollar exchange rate has been fixed. The price of franchises when they were auctioned was set in US dollars. In 2015, when the first five franchises came on board, the rate was PKR 105 to a dollar. Currently, the rate of a US dollar hovers above PKR 170. The agreed offer means the PCB will peg the US dollar to the day the new agreement is signed. International players will continue to be paid in USD, however.

To their credit, the PCB seems to have wrangled the franchises for now. “Whether the teams will become profitable or not is a question for the teams as the PCB cannot reveal these financial details, however, due to the unprecedented values achieved in commercial deals recently locked for PSL and the revised share percentage, it is fair to say that the franchises will receive substantially more revenue than any previous edition,” says Sami Ul Hasan, the board’s media director.

“The PCB makes money each year, and the franchises have consistently been making losses. This naturally caused a lot of grumbling regarding the financial model,” says Osman Samiudding, an author and cricket journalist.

“They’ve been operating in this sort of unhappy state for a while now. A few years ago a doc was leaked accidentally and it broke down what everyone had earned up until that point. What we can gather is that they are still invested, but maybe not every franchise necessarily in only a financial sense,” he adds. “For some it is as much about the influence and not just money.”

This is where another explanation comes in – about why the teams would want to stay on board even if they aren’t making money.

So why are the teams staying?

Pakistan needs the PSL. In the seven years that it has been around the tournament has not just brought in an influx of money and players to Pakistan, but the tournament has managed to maintain a high standard of cricket that has provided local talent a star-studded stage to showcase their talent. (Shaheen Afridi first played in the PSL in 2018 when he was picked in the ‘emerging’ category. In the four years since, he has risen to spearhead Pakistan’s pace attack, demolished the Indian batting line-up in the T20 World Cup, become the youngest player to win the Sir Garfield Sobers award for cricketer of the year, and is now leading the Lahore Qalandars as Captain in the ongoing tournament).

The question is, however, why these team owners need the PSL. Clearly the pull is not money here. Let us, for instance, talk about the relatively newer team in the League, the Multan Sultans. Late by just two years, the franchise was auctioned off for a whopping $41.6 million – and that too only for an eight year period to the Schon group. However, the $5.2 million franchise fee was too much for Asher Schon to keep up with, and after one year the PCB terminated the Schon group’s ownership of the Multan Sultans on good terms.

Even this, however, did not stop the price of the team from rising even more. Initially sold for a $41.6 million price tag for eight years, the team was now sold for $45 million for seven years to Aalamgir and Ali Khan Tareen. That meant the Tareens would be paying an astonishing yearly franchise fee of $6.35 million each year to keep ownership of their team.

“The amount that Multan paid was a very high one. The PCB will say that this is the value of their league, but it is difficult to see Multan break even for a while and this much money is only sustainable because they have it,” says Samiuddin.

So why did the owners fall into this trap? Well, maybe it isn’t a trap, but a toy. In a cricket crazy country like Pakistan, having a cricket team, which includes individuals who have worn the iconic Green blazer and others who have represented their own countries, is a vanity project like no other. A surprisingly large number of public figures (Nawaz Sharif, Atif Aslam, Faiz Ahmed Faiz to name just a few) think they could have played cricket professionally had they wanted to. A large number of businessmen also indulge this schoolboy delusion in their minds.

So what is the next best thing? – Basking in the high of packed stadiums chanting out the name of the team they own. Just think about it. Of the six teams, at least three have very prominent owners that have made their own brand synonymous with the team’s brand. Fawad Rana has become the iconically loveable face of the Lahore Qalandars, Javed Afridi has found his fame through his ownership of the Peshawar Zalmi, while Salman Iqbal has ventured beyond just the team to also buy the broadcasting rights for the league with his A Sports channel – something that gives him a large amount of influence over the league.

“Javed Afridi Yellow Stone Army; at the end of the day, we are all Pakistanis,” went a line, immediately before the chorus in Peshawar Zalmi’s rather catchy official rap anthem from last year. One can’t put a price on that ego boost. Well, one can. And Afridi did.

As Malcolm Gladwell writes on the motivation behind owning teams in the US’s National Basketball Association (NBA): “The issue isn’t how much money the business of basketball makes. The issue is that basketball isn’t a business in the first place — and for things that aren’t businesses how much money is, or isn’t, made is largely irrelevant….”

Very inspiring

Great Inspiration

thanks for best sharing its amazing keep posting best things these are lovely

i think this psl idea is great and thy are all earning a lot

Niazi sb, keep posting such kind of articles, good inspiration

What an amazing article I understand which I want

In the end, PSL is a rupee tree for PCB and a fruitless tree for the PSL franchise owners

The PSL is also perhaps one of the worst business decisions some of the franchise owners have made. Over the course of the past 6 years, the PCB has made a neat profit from every edition of the tournament in addition to collecting hefty “franchise fees” from all of the team owners. In comparison, only one or two teams have managed to break even, with the others facing consistent losses.

pavement marking

Great information about Pakistan Super League. Thanks for sharing.

PSL bussines model should be more liberal. If franchises will make a good amount of money, they in turn will also put more money into their franchise, resulting in better cricket (in fact promotion of cricket). PCB shouldn’t consider PSL as a cash cow, instead treat it as cricket promotion organization. After this 10 years ownership regime, PCB should also franchises to be sold life long, where owners have chance of reselling franchise (like we see in more advance leagues).

Bro can Psl become biger than ipl in future??

Great Read!

You are missing the elephant in the room. PSL broadcasting deal was done with PTV. So its basically the Pakistani tax payer paying for a domestic cricket league. This is not a bad idea in of itself, the government already supports domestic cricket and the PSL actually has a chance to be profitable in the long run.

Good post! We will be linking to this particularly great post on our site. Keep up the great writing

Great information about Pakistan Super League. Thanks for sharing.

I really enjoyed your blog Thanks for sharing such an information post.

Thanks for sharing this interesting information I never expect this from you. Keep going

“Thank you for the auspicious write-up. It in fact was a amusement account it.

Look advanced to more added agreeable from you! However, how could we communicate?”

온라인 카지노

j9korea.com

Very Instrusting

I really enjoyed your blog Thanks for sharing such an information post.