In early September, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) made a decisive move, signalling that it had had enough. It unfurled a sweeping set of reforms targeting exchange companies. These reforms were not just about tightening the reins on the open market; they were a strategic endeavour to bolster governance, enhance internal controls, and elevate compliance standards to new heights.

The SBP’s actions were fueled by apprehensions that exchange companies were failing to provide foreign currency to customers when it was available while also carrying out off-the-books transactions, resulting in substantial disparities between interbank rates and those offered by these companies.

Under the umbrella of these structural reforms, the SBP has given exchange companies three months to increase their paid-up capital and consolidate into a single category. It has also “encouraged” top banks to open exchange companies (more on that later).

The burning question is: What does this mean for the currency markets — is the central bank simply trying to rein in illegal activity and increase oversight of the open market, or does it plan to eventually phase out the open market completely?

Before the reforms

There are two legal currency markets in Pakistan: the interbank market which is made for and participated in by banks, and the open market which comprises exchange companies. According to the Standby Agreement signed with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in June, the difference in the rates cannot exceed 1.25% for more than five consecutive days.

This is because the central bank intervened in the interbank market in the past, including last year, to control the rupee’s depreciation by imposing an artificial cap on the dollar to rupee exchange rate. This makes imports cheaper and exports expensive, leading to a widening trade deficit and pressure on foreign exchange reserves. The IMF believes the open market is more difficult to coerce and so, by demanding that the rates align closely with each other, it was hoping the interbank rate would remain closer to the market reality.

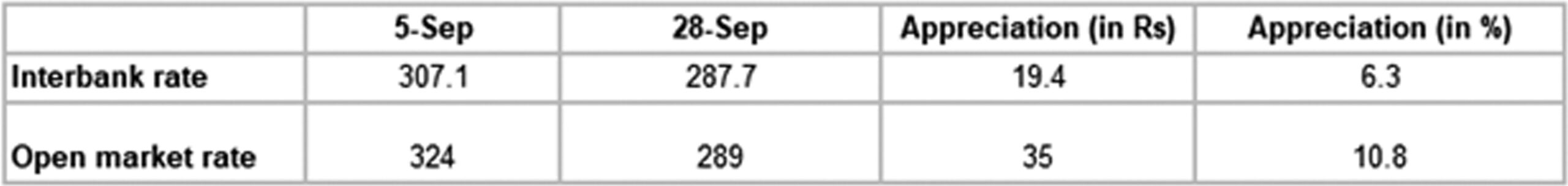

However, between August 28 and September 4, the difference in the market rates widened to an alarming extent both in absolute and percentage terms. For instance, on September 1, the interbank rate was Rs 305.46 per dollar while the open market rate was Rs 333 — a difference of Rs 27.54 per dollar or 8.27%. It appeared that the open market, which is less heavily regulated, was out of control. This is when multiple agencies launched a crackdown on illegal foreign exchange trade. They ramped up monitoring, placed officials at certain branches and raided offices of exchange companies suspected of being involved in conducting “off-the-books” deals that added to the exchange rate volatility. Consequently, the exchange rate started dropping from a high of Rs 334 on September 4. At the time of writing (September 28), the open market rate stands at Rs 289 per dollar. [You can read further details of the crackdown in Profit’s September 11-17 issue].

The new structural reforms

The crackdown was followed by structural reforms unveiled on September 6. Under these reforms, the SBP encouraged leading banks actively engaged in the foreign exchange business to establish wholly owned exchange companies to cater to the legitimate needs of the public.

There are two categories of exchange companies, A and B. According to the SBP, there are 27 category A exchange companies of which two are subsidiaries of banks — Habib Bank Limited (HBL) Currency Exchange (Pvt.) Ltd. and National Bank of Pakistan (NBP) Exchange Company (Pvt.) Ltd. There are also 21 category B exchange companies. Additionally, there are also franchises.

Previously, exchange companies in category A had a higher minimum capital requirement — Rs 20 crore — while those in category B had a lower minimum capital requirement of Rs 2.5 crore. The latter could only act as money changers.

Under the reforms, all exchange companies in categories A and B along with franchises of exchange companies will be consolidated and transformed into a single category with a well-defined mandate.

The minimum capital requirement for exchange companies for category A has been bumped up from Rs 20 crore to Rs 50 crore, free of losses.

Category B exchange companies have been given three options: merge with an existing exchange company, upgrade to full exchange company status, or consolidate with other category B exchange companies to form a unified entity. They must approach the SBP within one month for a no-objection certificate (NOC) for one of these choices. After receiving the NOC, they have three months to meet regulatory and legal requirements for formal licensing, failing which, their licences will be cancelled.

Meanwhile, franchises of exchange companies have been offered two options: either merge with the franchiser exchange company or sell the franchise to it. In either case, the franchises will have one month to approach the central bank for approval of the merger or sale. If they do not, their licences will be cancelled.

The goal of the reforms

Profit spoke to three treasury officials from three leading banks, and two officials of a bank-owned exchange company to understand what necessitated the reforms and what the SBP hopes to achieve.

(We will refer them as treasury official 1, 2 and 3)

Treasury official 1 said the SBP and the law enforcement agencies involved in the recent crackdown had “ordered” the top 10 banks to open exchange companies. While the NBP and HBL already had exchange companies, Meezan Bank Limited, Allied Bank Limited, Habib Metropolitan Bank, Bank Alfalah Limited, Faysal Bank Limited, Askari Bank Limited and Bank Al Habib Limited were also ordered to set them up. The orders “came from the very top”, the source said. Many of these banks have already made announcements in this regard.

In the coming months, exchange companies in category B will cease to exist and those in category A will find it very difficult to continue operating due to higher capital requirements and punishments for minor infractions, the treasury official said. Most exchange companies are small businesses whose profits come primarily from “off-the-books dealings”, and they are very hard for the SBP to regulate. This is why the central bank wants them to be phased out and replaced by larger, more regulated exchange companies led by banks, he commented.

According to treasury official 1, the SBP has directed banks to send letters of intent within one month, assuring them that licences would be granted within the next three months. These banks would then have between 10-12 months to set up at least 10 branches, or separate booths in existing branches, dedicated to foreign exchange dealings. The banks would also have internal oversight of these exchange companies.

“The market will eventually be heavily regulated and banks will handle the know-your-customer requirements much better than the existing exchange companies. Walk-in customers will also be allowed to sell or purchase foreign currencies provided they have the correct documentation, including possibly tax returns for higher amounts. The purpose of [these reforms] is to ensure that all foreign exchange dealings are done cleanly, legally and on the books.”

Meanwhile, treasury official 2 recalled that when incumbent caretaker finance minister Shamshad Akhtar was the SBP governor, she came up with the ideology of ‘big five banks’ — those “too big to fail”.

The idea is that when your paid-up capital is high, you have a significant financial investment in the business. Consequently, you cannot afford to engage in any wrongdoing because you have a substantial stake in the company. For example, if your capital is only Rs 2.5 crore, it may not make much of a difference. However, if you are required to invest Rs 50 crore, the paradigm shifts, the scale increases, and the business becomes much more professional. In such a scenario, you can no longer afford to engage in questionable activities or operate without proper adherence to regulations.

Moreover, the problem with category B exchange companies and franchises is that compliance controls have regrettably shown a tendency to be less stringent. This, understandably, raises red flags for the regulatory authorities, particularly in light of their commitment to meeting the rigorous standards set forth by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

Therefore, to strengthen control and compliance, the regulator and the government want to phase out category B exchange companies and franchises. And the regulator has taken this job very seriously. In less than a month, the central bank has suspended or revoked the licences of four exchange companies.

Profit reached out to the SBP’s Exchange Policy Department for more clarity on its plans but an interview could not be arranged at the time of writing.

The results so far

The effects of the agencies-backed administrative measures and the resulting sentiment-driven market forces are already visible. The rupee has fallen below the Rs 300 mark in both the interbank and open markets and the premium is within the IMF-mandated range.

The rupee’s appreciation is also gradual this time around, instead of volatile. It has also been very consistent, around Rs1-1.50 daily. This suggests that the recovery of the rupee is being managed in a very controlled manner, and for good reason.

Because there is excess supply of dollars in the interbank, the SBP purchases these at a certain rate (Rs1-1.50 below the previous day’s closing rate) every day to remove that liquidity from the market and arrest any further weakening of the dollar during that day’s trading. What happens as a result is that the USD/PKR does not drop by too much during any particular day.

For example, on Monday the market closed at 290/292. The following day on Tuesday, there is an inflow of exports and inward remittances that is well above the amount of imports and outward remittances. This means that banks cannot fully offset these inflows against their outflows and will therefore have to sell dollars in the interbank.

Most banks these days are facing the same predicament and therefore the interbank is flush with supply of dollars, and if left unchecked, such liquidity can cause the dollar value against rupee to fall considerably. So what the SBP does is that it enters the interbank market and buys up this liquidity at 289.50/290.50, Rs 1.50 less than the previous day’s closing rate. By doing this, it sort of mops up the excess dollars at a rate below the previous day’s lowest rate. This restricts any major downward dollar movement in a single day.

“While the central bank is looking to take the USD/PKR down to a certain level, it does want to do that too rapidly as it would not only irk exporters but also encourage importers to open more LCs and those ‘dollar investors’ to start buying and hoarding again if the rate goes too low too fast”, explained treasury official 1.

Following the rupee’s appreciation, exporters have rushed to bring back their export proceeds [they tend to hold their proceeds or payments abroad if they expect the rupee will depreciate and they will get more Rupees; under SBP rules, the time limit for bringing export proceeds back is 120 days]. They have booked forward proceeds amounting to $1 billion so far, according to treasury official 1.

Let’s say that an exporter has sold clothes worth $10 million dollars to its buyer in the US. The exchange rate on the day that he sends out his shipment — called spot or ready rate — is Rs 288. He is set to receive payment for his export in two months. However, he expects the rupee to appreciate further in that time, which means he could possibly be getting Rs 278 per dollar. To protect himself from the appreciation, he goes to a bank to book forward proceeds. The bank offers him a premium of Rs 1.5 per dollar. This essentially means that the exporter has agreed to sell his dollar proceeds (due at a later date) to the bank today, at a rate of Rs 289.5 per dollar. [There is a downside to this – the rupee may depreciate in the coming two months and he may lose money instead. If, for example, the spot rate two months later is Rs 290, he will have lost 50 paise per dollar.]

Exporters across the country have repeated this process multiple times. This indicates that they expect the rupee will continue to appreciate, at least in the short term. This is why the maximum period of these export forwards is just two months as opposed to six months; this recovery, in exporters’ view, is not going to last more than a few weeks.

How have exchange companies reacted?

The mood among exchange companies is far from content. The recent decision to grant banking licences for exchange companies has rattled the industry, sparking strong resistance. Exchange firms view the entry of banking giants into their domain as an existential threat, with their very survival hanging in the balance.

Profit spoke to Malik Bostan, chairman of the Exchange Companies Association of Pakistan (ECAP) and Zafar Paracha, general secretary of ECAP.

Paracha expressed his concerns bluntly, stating, “The way things are, it seems that exchange companies might be forced to shut down. If the government believes that the private sector should not exist, they should inform us, and we will close our business. The SBP doesn’t even need to provide us with a roadmap.”

Bostan lamented the crackdown on exchange companies, asserting that every sector has its “black sheep”, and tarnishing the reputation of all exchange companies is unwarranted.

Paracha expressed his views on having the currency exchange business owned by banks. “This model will fail,” Paracha put it bluntly. He argued that shutting down exchange companies could pave the way for the rise of an informal market or “grey market” for foreign exchange, which would be more prone to manipulation.

Bostan also asserted that banks have a history of manipulating exchange rates, alleging instances where banks purchased dollars from exchange companies and subsequently charged customers higher rates, artificially inflating the dollar rates. This underscores apprehensions regarding the potential consequences of sidelining exchange companies in the foreign exchange landscape.

According to Bostan, bank-owned exchange companies haven’t seen much success.

How have banks reacted?

In a swift response to the central bank’s recent reforms, United Bank Limited wasted no time in announcing its venture into the exchange company arena on September 12, six days after the reforms were rolled out. UBL’s move triggered a domino effect, with a lineup of other banks swiftly joining the fray. Meezan Bank Limited joined the list three days later. In the following weeks, more banks followed suit which included MCB Bank Limited, Bank AlHabib Limited, Allied Bank Limited, and Faysal Bank Limited. HBL and NBP already had an exchange subsidiary as mentioned earlier.

An official from a bank-owned exchange company that Profit spoke to stated “this was long overdue”, “logical” and a “positive development”. He also added that they see the exchange companies and the banking sector from a treasury perspective coalescing together.

Are bank-owned exchange companies lucrative?

While speaking to Profit, both Bostan and Paracha claimed that the banks have not been successful in the exchange company business.

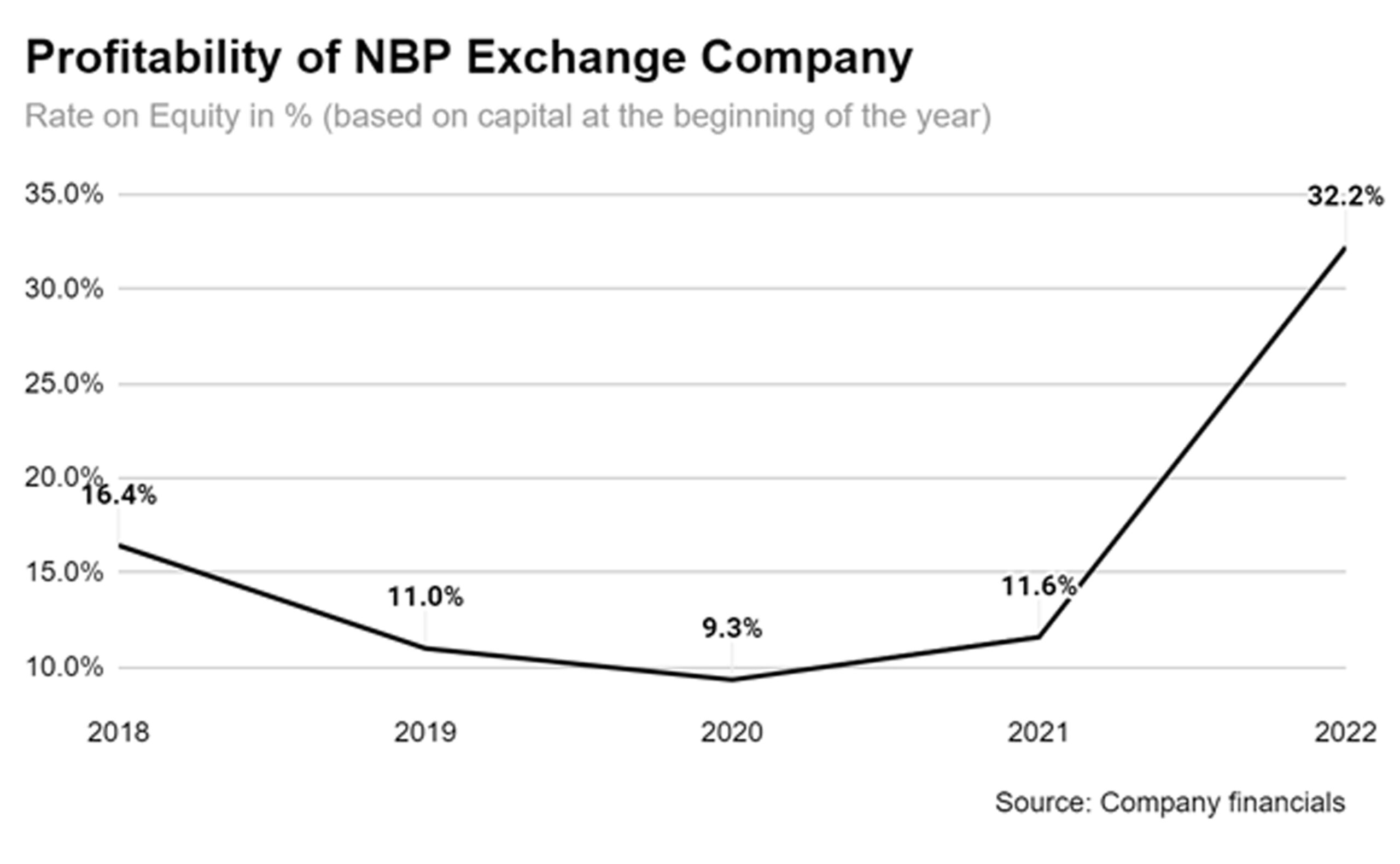

An official from a bank-owned exchange company disclosed that “they hardly make any revenues”. He added that “we have maintained a conservative position”. However, their return on equity exceeds 22%.

We also looked at the financial statements of the NBP Exchange Company. In 2022, it recorded the highest-ever return on equity of more than 30%.

What about the new entrants? Will they be just as successful? According to treasury official 3, it is very likely that exchange companies of banks will be successful. He cited two reasons for this — first, the foreign exchange business is generally a lucrative one because banks (and exchange companies) usually have customers on both sides of the trade and they earn from the spread in both transactions, and second, better management of cash flow positions. In addition, the costs will be lower for banking exchange companies as they would be operating out of the current existing branches of the banks and most of the required hardware and software would already be present in the branch, he commented.

Business model of a bank-owned exchange company

One of the primary sources of revenue for the bank-owned exchange company is the standard spread of buy and selling rates. These rates are set by the ECAP daily, typically at 1%. This spread serves as a limited source of income.

The other source is through positioning. The SBP permits category A exchange companies to maintain a portion of their paid-up capital in foreign exchange. This means that they can hold up to 50% of their capital in foreign currencies. This provision enables these companies to actively engage in currency trading. When the value of the dollar increases, they can generate gains due to their currency positions.

Conversely, if the dollar’s value decreases, the exchange companies resort to reducing their position by selling the greenbacks to banks’ treasury to minimise potential losses.

One of the most significant expenses incurred by the exchange company is related to Cash in Transit. The company purchases various foreign currencies like riyal, dirham, pounds, euros, and damaged cash dollars received at its counters, consolidating them at central locations — typically Karachi, Lahore, or Islamabad, depending on flight availability. These physical currencies are then sold in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, with the proceeds converted into dollars and deposited into the exchange company’s NOSTRO accounts (these are essentially dollar accounts held with foreign banks).

Originally, electronic dollars in these accounts were used for settling credit card payments. However, the game changed in June when the SBP granted banks the authority to purchase US dollars from the interbank market for settling cross-border card-based transactions. As a result, the exchange company now sells various currencies, including dollars, to banks and individuals for this purpose.

Electronic dollars aren’t just sitting around, though. They are also withdrawn from NOSTRO accounts and handed out as physical cash to individuals. Moreover, these electronic greenbacks are used for settling imports and conducting treasury operations with other banks, being transferred to other banks’ NOSTRO accounts as needed for various financial transactions.

Will banks dominate the currency exchange business?

Let’s break it down: Imagine you’re running a franchise or a category B exchange company, and suddenly, you’re told to take your capital from a modest Rs 2.5 crore to a whopping Rs 50 crore in just three months. Realistically, that’s a tall order, and for many, it’s a challenge they might struggle to meet.

So, what happens next? Well, category B exchange companies and franchises would either merge or be forced to shut down. This would leave a gap in the market. To bridge this gap, regulators have encouraged banks to step in and play a role in this space.

Does this mean that only banks will remain in the exchange business? The short answer is no.

An official of a bank-owned exchange company told Profit that it is premature to assume that banks will outright dominate the landscape of exchange companies at this juncture. Instead, the vision is one of coexistence, where both bank-owned exchange companies and other category A players operate on a level playing field.

Moreover, if we look through the lens of paid-up capital – currently, there’s a club of 27 category A exchange companies, and interestingly, just two of them are bank-owned. Now, here’s the fascinating part: the majority of these category A companies boast capital ranging from a substantial Rs 50 crore to an impressive Rs 1 billion.

What does this mean in the grand scheme of things? It’s a clear sign that the exchange company sector won’t be exclusive territory for banks, as some market sentiments may have suggested.

However, bank-owned or not, all category A exchange companies have to follow stringent conditions if they want to keep operating.

The survival of these businesses teeters on their ability to navigate this regulatory maze. One standout requirement demands an unrelenting 24/7 recording of transactions. These recordings encompass both audio and video footage of personnel working at the exchange counters. Companies must maintain recordings for the past six months, readily accessible at any given moment. Failure to comply with this crucial provision can result in a suspension of transaction privileges at their counters. Adding to the scrutiny, audits conducted by the SBP include meticulous examination of these recordings. The SBP cross-references recordings with transactions, demanding explanations in cases where discrepancies emerge.

Moreover, conducting currency exchange transactions beyond the registered place of business is now strictly off-limits unlike in the past when one could ring up an exchange company and a company representative would deliver currency to your location or office.

The emphasis is crystal clear: only those companies meticulously adhering to compliance processes will be permitted to continue operations.

Will the open market phase out?

The future of the open market and its potential convergence with the interbank market has been a subject of curiosity since banks have been rapidly establishing exchange companies.

While some questions persist, here’s what three insiders shared with Profit.

According to an official of a bank-owned exchange company, the open market is expected to continue to exist. However, there’s a crucial caveat: it will continue to exist within the framework of rules and regulations mandated by the government and regulators, something that it was not made to do very diligently by the regulator in the past. Therefore it will take some getting used to.

Treasury official 3 elaborated on this, emphasising that the foreign currency cash market and the interbank market are distinct entities. While it’s expected that rates will converge and the cash foreign currency market’s volatility will diminish, they won’t become identical. This disparity stems from various additional costs inherent to cash market transactions. One notable cost is the cost of cash in transit which arises when cash foreign currency is transferred to the NOSTRO account of the bank.

Conversely, Bostan believes that the gap between the open market rate and the interbank rate could potentially widen. This divergence is expected because people may choose to refrain from bringing foreign exchange into the market.

Will these actions be enough?

The net result of all of this are some very encouraging news reports of the Pakistani Rupee being on its way to claim the ‘best-performing currency title in September’. That is all well and good but this thumping victory of the rupee over the dollar must be taken with a little more than a pinch of salt.

Yes, these gains are impressive, but are they sustainable? As we have mentioned in our previous articles, all the measures being taken are administrative in nature and they have created a sentiment in the market that the rupee will continue to make strides against the greenback, but only to a point.

The interim federal minister for industries Gohar Ejaz, who also happens to represent the largest representative body for exporters, APTMA, feels the dollar will bottom out at 260. Others feel it will be 250. But from that point onwards there will be a gradual move in the opposite direction.

Why? Because our fundamentals remain intact and unchanged. We have to make loan repayments in dollars and we have to import oil, in dollars, both of which are major outflows. And while these are being taken care of by exporters rushing to sell their dollars at the moment, there will come a point, not too long from now, that these proceeds will dry up. We are after all a net importer of goods and services.

Additionally, a weaker dollar means our exports have become expensive and therefore, there will be shrinkage in volumes as booking deals with foreign buyers will become more difficult. As far as remittances go, the rupee amounts will be getting lower as the dollar weakens in the coming weeks, so perhaps some people hold off on those as well for a bit.

Add to this the fact that a lot of export proceeds that were going to be coming in after two months and add supply to the interbank have already been factored into the market as exporter have book forwards in droves (almost $1 billion we are told). So a slight recovery by the dollar within 60 days will coincide with very little export proceeds coming in, thereby putting added pressure on the rupee-dollar parity and possibly on the current account deficit as well.

The policy to move exchange company business from the under regulated ‘fast and loose’ open market to the over regulated banking industry may not be very well liked by the open market, but it is somewhat necessary. And even though banks are not very keen on doing this, one thing is for sure, they will make it work financially for themselves and play within the confines of the SBP regulations. This will introduce much-needed formality to the currency exchange market.

But let us not fool ourselves. The vulnerabilities of our currency market remain intact. And once tested again, they will become very visible, very quickly. It remains to be seen what the ‘shot-callers’ do then.

None is out there with clean hands in this Land of the Pure. These very banks now planning to open currency exchange companies have been involved in money laundering and terror funding in the past resulting in dragging the country onto the FATF’s radar and the consequences are known to all of us. Not only that, these banks have also been associated with the many irregularities witnessed in the open market foreign currency exchange rate manipulations. Rather than instilling discipline amongst these private exchange companies through enforcement of law, the hands of banks are being strengthened further to benefit them rather than the people. I have been personally witness to the poor performance of a currency exchange company associated with a commercial bank. Anyway, the motive is not clear, the consequences even more dim.

You Providing Always Good Conten. Thanks For Regular Updates

Your Website Design is Very Nice Also Your Post is Very Good. Please Update Daily

@Aam Admi: It seems you have been impacted by the compliance policies of banks and forced to join the Exchange Companies. Banks deal with open market Forex trades world over. Look at Turkey, you can buy from bank or exchange company it’s your convenience. Unfortunately exchange companies started making forex a satta business. Genuine Aaam Admi was told forget about ECAP rates rates at my “shop” are demand and supply driven (Source a prominent Exchange Company at Khy e Ittehad- my first hand experience)

Great blog post! The State Bank of Pakistan’s bold reforms are set to reshape the currency markets, promoting transparency and accountability. Exciting changes lie ahead in the financial sector

Wow Really This News Portal Providing Time to time Content, Thanks

Thank You For Making this Site And Provide Very Helpful News, Really You Are Doing Great Job

Big banks” generally refers to large financial institutions that play a significant role in the global or national economy. These institutions typically have extensive resources, large market capitalization, and a broad range of financial services.

I appreciate you distributing this useful blog.criminal attorneys in prince william county

Wow Really You Are Providing Ver Good Information, Thank You For This Information