In Pakistan’s energy sector, nobody seems to want to go to the disco. Excuse the very obvious pun, but the state of the country’s power distribution is such that almost everyone wants to steer clear of the DISCOs with a ten-foot pole.

Perhaps nothing captures this better than a recent damning report of the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA). Unveiled in December 2023, the report laid bare the illicit and unlawful manoeuvres of the DISCOs that led to millions of consumers shouldering inflated bills for the months of July and August.

The severity of NEPRA’s indictment? Throughout the two-month period, millions of Pakistanis were billed for electricity consumption exceeding the standard 30-day monthly billing cycle. To compound the issue, the electricity slab for millions was altered due to the overcharging, resulting in higher rates. Very simply put the DISCOs, which are responsible for billing consumers for electricity, were making up the bills. Adding salt to the wound, millions of the most economically vulnerable consumers — those whom the State of Pakistan purports to shield with its flawed subsidy policies — found themselves bereft of subsidised rates and subjected to those applicable to regular consumers.

The DISCOs occupy a strange place in Pakistan’s energy history. No one is quite sure who is, or more appropriately, who should run them. From suggestions to devolve them to the provinces and to recent bright ideas like handing them over to the military it seems no one quite knows what to do with this little problem. Most also do not quite understand what they do, where they came from, or why we need them.

So we asked ourselves, what exactly are these DISCOs and is there a better way to run them? What started off as a simple question quickly evolved into what is a comprehensive history of Pakistan’s DISCO problem.

What is a DISCO?

The connotation of the word DISCO around the globe is vastly different from its designation in Pakistan. In Pakistan, ever since the 1970s, it does not conjure up any notion of leisure or entertainment. The only resemblance it bears to its international equivalent is the monetary agony one experiences when they behold the bill. This is because the word ‘DISCO’ is an acronym for Pakistan’s electricity distribution companies.

These are the companies whose name is emblazoned on your electricity bill at the commencement of every month. These are also the companies that we contact when we are deprived of electricity for interminable hours, when there is a malfunction in the wiring, or when our local transformer is defunct, among other things. At this juncture, the name of the DISCO that will have sprung to your mind will vary depending on your location throughout the expanse of Pakistan. There are presently 12, with the newest one emerging only this year, whilst the oldest one tracing its origins to the early 20th century.

So, how did these DISCOs come about?

Our forgotten energy history

Before Pakistan came into existence, its DISCOs were already lighting up the region. Among them, K-Electric stands out as the most renowned, and deservedly so. Established in 1913 under the Indian Companies Act of 1882 during the British colonial epoch, the Karachi Electric Supply Corporation (KESC) — now known as K-Electric — holds the distinction of being Pakistan’s oldest DISCO in ceaseless operation. The company was initially founded with a humble capital of Rs 13 lakh, to satiate the escalating demand for electricity in Karachi as the city’s populace surged past the 100,000 milestone. It is not, however, the oldest of the DISCOs. That distinction belongs to the Lahore Electric Supply Company.

Before we proceed, let us clarify a crucial point: the Lahore Electric Supply Company that we are about to discuss bears no relation to the contemporary one that goes by the acronym LESCO. They are distinct organisations that coincidentally share the same appellation. We shall revisit the latter version in due course, but for now, let us focus on the original DISCO.

The Lahore Electric Supply Company materialised in February 1912, with a capital of Rs 5 lakh. Nestled at the junction of McLeod-Cooper Road, it was the brainchild of Lala Harkishen Lal, a Lahore based industrialist, who ascended to the position of its inaugural Chairman.

The Lahore Electric Supply Company was one of the many enterprises that Lal initiated. He was a co-founder of the Punjab National Bank, the founder of the Punjab Cotton Press Company, the People’s Bank of India, the Amritsar Bank, and the Kanpur Flour Mills, to name a few.

As the decades rolled on, more companies sprouted within the geographical boundaries of what is now Pakistan. The Multan Electric Supply Company was established in 1922, the Rawalpindi Electric Power Company in 1923, the Small Town Electric Supply Syndicate in Muzaffargarh in 1935, and finally, the Attock Electric Supply Company Campbellpur in 1939.

These companies can be viewed as the historical precursors of Pakistan’s modern DISCOs — there are contemporary precursors too, but we’ll delve into them shortly. Of these original companies, those based in Karachi, Lahore, and Rawalpindi can be deemed the most successful ones, judging by the available data. KESC continued to illuminate Karachi and its surrounding areas, whereas the other two expanded beyond their initial frontiers. The Rawalpindi Electric Power Company procured the licences to electrify Jhelum in 1928, Abbottabad in 1931, and Gujar Khan and Chakwal in 1935. As for the Lahore Electric Supply Company, by 1941, it was powering as many as 12 towns located in other provinces of the country, including the Central Provinces, the United Provinces, Sindh and the North-West Frontier Province. It was the single largest power generating entity outside the Government Electric Supply Branch system.

By the time partition dawned, only KESC, the Rawalpindi Electric Power Company, and the Multan Electric Supply Company remained operational. What befell the rest?

The Attock Electric Supply Company Campbellpur was incorporated into the Rawalpindi Electric Power Company, according to the records. The fate of the Small Town Electric Supply Syndicate in Muzaffargarh remains a mystery. The Lahore Electric Supply Company, on the other hand, met with a rather intriguing denouement. By 1942, all of its licences — bar the one for supplying electricity to Lahore — were terminated or disposed of. The company’s downfall stemmed from a conflict with the Government of Punjab that erupted in May 1934, after which the government sought to annex the company. The Punjab Electricity (Emergency Powers) Act, 1941, is most likely the legal instrument that heralded the end of the company. Consequently, by 1946, the Lahore Electric Supply Company had also forfeited its licence to serve Lahore. The company lingered on as a defunct entity, managing its proceeds instead of providing electricity, until the early 1950s in the newly formed Pakistan.

The fate of the remaining duo of Punjab-centric corporations, albeit divergent, remains murky. No tangible evidence exists regarding their evolution post-partition until the advent of the 1980s. The most credible conjecture suggests their integration into the Government of Punjab in some capacity. This supposition stems from the nascent state of Pakistan’s electrical infrastructure.

“In the beginning, electricity was a matter confined to provincial jurisdiction. It didn’t command national attention. The focus was solely on generation within urban hubs and subsequent distribution within these same centres,” expounds Himayat Ullah Khan, a former Federal Secretary at the Ministry of Water and Power, and a former Energy & Power Advisor to the Chief Minister of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

KESC was the most notable aspect of Pakistan’s electricity infrastructure at the time. In 1949, KESC became the first utility to obtain registration from the Karachi Stock Exchange. By 1951, it had become an organised and profitable entity. Despite the company becoming nationalised pursuant to the the Electricity Control Act, 1952 (Sindh), it was the most important part of Pakistan’s electricity infrastructure.

This state of affairs persisted until the pivotal year of 1958.

WAPDA, and the creation of Pakistan’s modern energy infrastructure

The sector underwent a formal planning process after the Planning Commission devised the first Five-Year Plan (1955-1960). Envisioned as the blueprint for Pakistan’s economic metamorphosis, the Five-Year Plans were a series of nationwide, centralised economic strategies and objectives. These plans were inspired by the quintessential five-year plans of the Soviet Union. The concept was the brainchild of the then Finance Minister, Malik Ghulam Muhammad, who proposed it to the then Prime Minister, Liaquat Ali Khan. Spanning half a century — from 1950 to 1999 — eight such plans were crafted and executed.

In 1956, the Pakistan Government realised the imperative to establish and equip an electric system of each region on a national basis. However, 1958 was the pivotal year in the five-year period. In February of that year, under the Federal Ordinance, the Electricity Department of each region and province integrated. Subsequently, in April 1958, the West Pakistan Water and Power Development Authority (the precursor of WAPDA) was born as a specialised corporation. Its mission was to harness water resources effectively for irrigation, flood control, and to cultivate electricity sources and manage electricity supply enterprises.

WAPDA was an autonomous and statutory body under the administrative control of the federal government. Its purpose was to coordinate and provide a unified direction to the development of schemes in the water and power sectors, which the respective Electricity and Irrigation Departments of the Provinces had previously handled.

Everything going forward hinges on what transpired in this period. Especially so because the creation of WAPDA resulted from another player entering into Pakistan’s electrical fray — the World Bank. This was the period when the World Bank intervened in Pakistan and assisted in developing the master plan for an integrated power system through the “Water and power resources of West Pakistan: a study in sector planning”.

Upon its inception, WAPDA was entrusted with two major responsibilities: to meet the electricity demand of the country (except for Karachi) by installing new power plants, transmission lines, and distribution systems; and to develop hydro storage projects (dams) for meeting the irrigation and power needs of the country and install hydro plants at dam sites. WAPDA was bifurcated into two wings: the Power wing, responsible for power matters, and the Water wing, responsible for water matters. The former becomes pertinent to our story later on.

WAPDA swiftly ascended to become the best-financed agency in the country. In the 1960s, WAPDA administered 41% of the total West Pakistan development budget, excluding expenditures on the Indus Basin. If Indus Basin expenditures are included, WAPDA’s budget amounted to an average of 70% of West Pakistan development budget. Similarly, the lion’s share of foreign aid funds fell under WAPDA’s administration. In the 60s, approximately 46% of total foreign aid (again excluding Indus Basin Funds) came under WAPDA’s purview, while the remainder was split over all the other sectors. If the Indus Basin is included, WAPDA was administering about 75% of the aid available to West Pakistan and roughly 50 to 55% of the total aid to Pakistan.

It was also during WAPDA’s heyday that it introduced the unified tariff for the country in 1969. This too is something that haunts our sector to this day because it is something only WAPDA could pull off, but we’ll get to that later.

The monumental project of the Indus Basin Works — which encompassed the building of the Mangla and Tarbela Dams, eight link canals, and five barrages — represented the most significant venture in Pakistan at that time. Consequently, WAPDA became the most influential agency in West Pakistan. The Indus Basin Works were, however, the last major hydropower project until the Ghazi-Barotha Hydropower Project in 1995. Consequently Pakistan entered the 1980s with a crisis that was poised to hit it in the face.

Until 1972, WAPDA existed in a symbiotic relationship with semi-private utilities. This equilibrium was disrupted under the regime of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, who promulgated the “National Economic Reform Order”, catalysing the swift nationalisation of a plethora of industrial plants. This included the private constituents of KESC, Multan Electric Supply Company, and Rawalpindi Electric Power Company from the energy sector. Intriguingly, this era also witnessed the genesis of discourse on the unbundling of WAPDA.

A watershed event that underscored the necessity for, and ultimately precipitated, WAPDA’s unbundling, was the realisation that the integrated power system was burgeoning into an entity too gargantuan for WAPDA’s solitary management.. The fourth Five-Year Plan (1970-1975) pointed to “serious doubts having been expressed about the ability of WAPDA to shoulder the responsibility of retail distribution of power, along with the construction of major power and irrigation facilities. Consideration, therefore, should be given to the bifurcation of the power wing from WAPDA.” The plan also proposed an alternative strategy to hand over the retail distribution to an ‘autonomous’ power corporation.

The mid-1970s marked the advent of the first power crunch, triggered by a surge in demand. However, this was adroitly mitigated as the hydel power station of Tarbela, along with several thermal power stations, became operational — providing respite for approximately a decade. Nevertheless, the military coup d’état of 1977 indefinitely deferred the plan to restructure WAPDA.

The 1980s was the penultimate decade before the establishment of Pakistan’s DISCOs. It was during this decade that the groundwork for their inception was laid. In 1981, under the auspices of the World Bank, the WAPDA Act was amended to engender Area Electricity Boards (AEB) within WAPDA. These entities, the precursors of our modern DISCOs, were tasked with the responsibility for local electricity service in specific areas. Eight AEBs were established within WAPDA: the Peshawar region encompassed the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the Quetta region enveloped Balochistan, and the Hyderabad region incorporated Sindh, excluding Karachi (KESC). Punjab was divided into four regions: Gujranwala, Lahore, Faisalabad, and Multan. Additionally, an Islamabad Region was created to cover parts of Punjab and Islamabad itself.

The 1980s also witnessed the extinction of private sector utilities. The Quetta Electric Supply Company was delisted from the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) on 14 June, 1981. It bears repeating that, akin to the precedent of the Lahore Electric Supply Company, this Quetta Electric Supply Company stands distinct from the contemporary Quetta Electric Supply Company, colloquially known as QESCO. This is merely a fortuitous coincidence, or perhaps a dearth of originality. It is in the 1980s that KESC was finally reigned in and was made a subsidiary of WAPDA in 1984, yet managed to retain its listing on the PSX for reasons unknown. The Rawalpindi and Multan Electric Companies were not as fortunate, both being delisted on September 18, 1985.

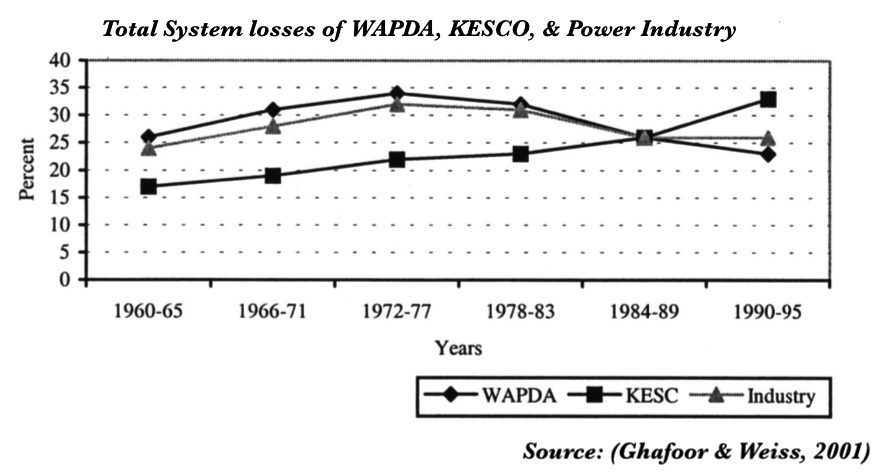

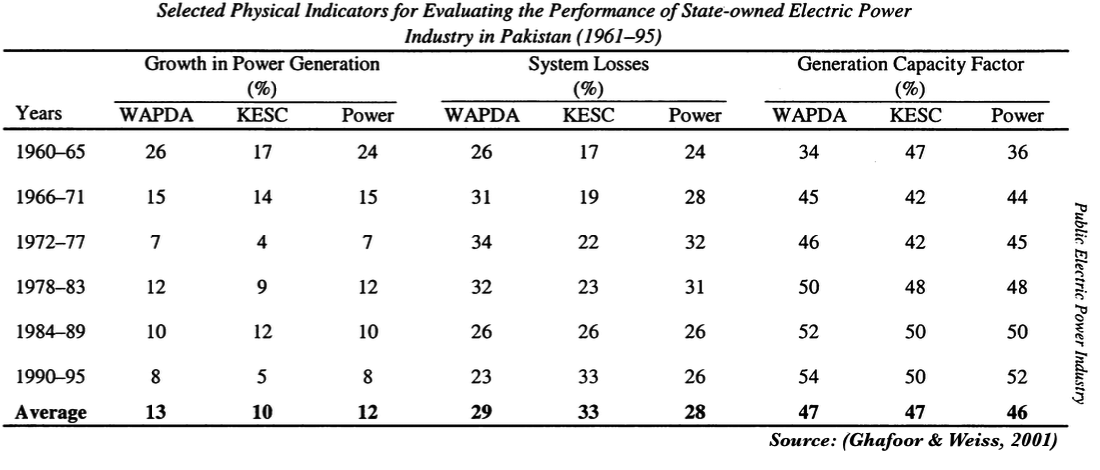

By the mid-1980s, the gargantuan, interconnected power system was besieged by conspicuous issues. The nation was grappling with recurrent breakdowns, power outages, and shortages. A multitude of critics pointed fingers at the generation capacity of WAPDA and KESC, accusing them of failing to manage the crisis during the 1980s. However, the average generation capacity factor for the entire power sector (46) was on par with other developing nations such as Hong Kong (43), Malaysia (42), and the Philippines (46.9). Consequently, the dearth of electricity could not be ascribed to inefficient utilisation of the existing installed capacity.

Nevertheless, in the realm of electricity, the total production might deviate from the actual delivery to the consumers. Herein lies an issue that we hear about till this day — system losses. These losses could have originated from technical complications such as unreliable and ageing generation plants, low-voltage transmission and distribution lines, and inappropriate location of grid stations, as well as non-technical factors such as inaccurate metering and billing, default payments, un-metered supplies, and theft (through illicit connections).

Throughout the period from 1960 to 1995, the average system losses (28%) in Pakistan’s electricity infrastructure were significantly higher than in other developing countries such as India (19%), China (15%), the Philippines (19%), and Hong Kong (11%).

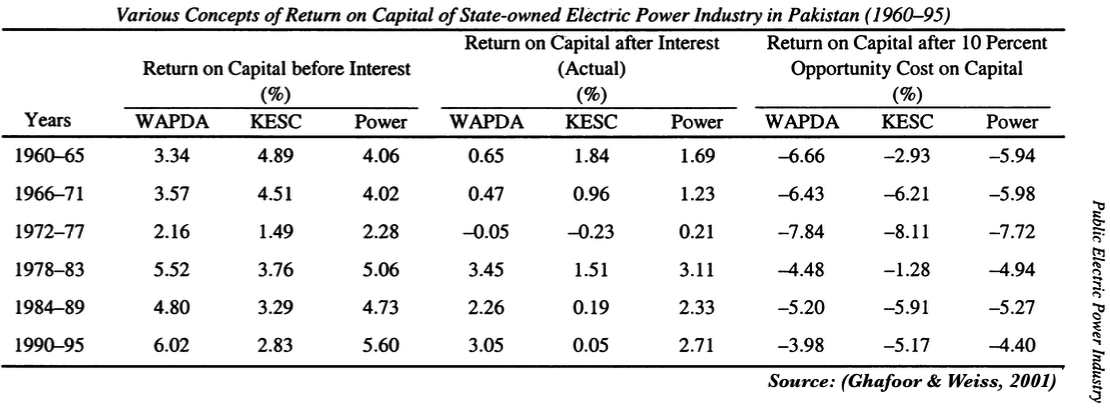

In terms of financial performance, both KESC and WAPDA also underperformed from 1960 to 1995. Although WAPDA marginally outperformed KESC, neither of the enterprises had achieved satisfactory results in the long run from 1960 to 1995. For instance, in terms of financial performance, the average annual net profit after interest, as a proportion of sale for both WAPDA (12%) and KESC (9%), was substantially lower than the net profit for the public corporation for electricity in Turkey, i.e., in the range of 20-36%.

In terms of economic performance, total factor productivity growth — growth in output that is not attributable to growth in factor inputs — had been negative in the case of KESC and relatively low in the case of WAPDA. The need for reforming these enterprises was compelling, and alternative modes of organisation, finance, and ownership were being explored. While privatisation was a viable option, it mainly stemmed from the desire for improvement on past performance.

However, context is crucial. Donor financing for thermal power in the public sector had dwindled because it became trendy to involve the private sector in power generation. WAPDA, and consequently Pakistan had no hydropower projects lined up, and the international financial institutions also started advocating private power. The dye was essentially cast.

By the dawn of the 1990s, WAPDA had morphed into a colossal burden. The power sector was besieged by operational inefficiencies that screamed for a comprehensive overhaul. As early as 1991, the government had directed WAPDA to kick-start the privatisation of certain operations. However, it wasn’t until 1992 that the government, under the stewardship of Nawaz Sharif, decided — prompted by the recommendations of loan lending agencies such as the IMF and the World Bank — to craft and endorse the ‘Strategic Plan for Restructuring the Pakistan Power Sector (PPRSP)’. The political baton’s transition from Nawaz Sharif to Benazir Bhutto halted the unbundling process.

Benazir reignited the potential unbundling of WAPDA, a vision encapsulated in the 1992 Strategic Reform Plan by passing an amendment to the WAPDA Act in 1994. This amendment empowered WAPDA to gear up to “privatise or otherwise restructure any operation of WAPDA except hydel generating power stations and the national transmission grid”. Yet, the political pendulum swung once again, obstructing the unbundling as Benazir’s government was supplanted by Nawaz’s.

In 1997, Nawaz Sharif reclaimed power and the policy towards the power sector resumed with the actual unbundling of WAPDA — the power wing was fragmented into 12 incorporated state-owned entities, comprising three thermal generating companies (GENCOs), one National Transmission and Dispatch Company (NTDC) — responsible for both transmission and the single-buyer market clearing entity — and the separation of the eight AEBs into eight regional distribution companies (DISCOs).

Established in 1998 by another amendment to the WAPDA Act, the Pakistan Electric Power Company Limited (PEPCO) was a temporary custodian of WAPDA’s assets and operations. With a two-year mandate, PEPCO was entrusted with the responsibility of disintegrating and privatising WAPDA components, transforming WAPDA from a bureaucratic behemoth to a corporate, competitive, and efficient organisation, and managing the thermal generation plant that was previously under WAPDA’s jurisdiction. In short, it was supposed to be new boss of Pakistan’s DISCOs

Beginning of the end

What is the first thing that Pakistan did after unbundling its DISCOs, and creating a new entity to manage them? Hand them over to the Pakistan Army in January 1999 — a full nine months prior to the Musharraf coup d’état of October 1999.

The Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) was on the brink of financial disaster in 1998, owing to a multitude of factors. The Government revealed that by the end of 1998, WAPDA had accumulated a deficit of Rs.45 billion (roughly US$870 million at the time) — a staggering amount that was projected to soar to Rs.74 billion (approximately US$1.43 billion at the time) by June 1999. This would have inevitably resulted in the dissolution of WAPDA. Without funds to pay the salaries, the organisation would have laid off tens of thousands of workers. Moreover, it would have crippled the entire country, rendering the lives of the citizens unbearable.

Hence, to prevent a total meltdown of WAPDA, the federal Government handed over WAPDA and the new DISCOs to the Army. The Army was thus tasked with assisting the WAPDA management in restoring the financial viability of the organisation by curbing pilferage and power theft. The Government emphasised that this was a desperate measure and taken solely to revive WAPDA.

A three-star general was appointed as the Chairman of WAPDA, and consequently the Chairman of PEPCO. Likewise, one-star generals were assigned to lead the various DISCOs, including KESC.

The Army’s involvement in WAPDA spanned two phases. In the first phase, which concluded on 25 July 1999, 31,444 army personnel were deployed to WAPDA. After 25 July 1999, only about 10% of the army personnel remained and the rest returned to their units. The army personnel aided the organisation in: (a) removing unauthorised connections, which numbered in the tens of thousands; (b) replacing faulty metres; (c) ensuring prompt and accurate billing; (d) checking the metres by surveillance teams; (e) issuing detection bills where theft was detected; (f) maintaining the system to minimise technical losses; and (g) launching a recovery campaign to collect public revenue. These specific benchmarks would become the standard for all anti-theft campaigns in the power sector in the future.

The Army also had an additional mission that it had to accomplish within a two-year period, after which, as a logical consequence, it would withdraw, as by then WAPDA would have been unbundled through the process of corporatisation, with some of its offshoots, such as FESCO, LESCO, and at least two generation companies, securely transferred to private hands. Regrettably, none of the aforementioned materialised.

The next major development for the DISCOs came across 2001 and 2002 when NEPRA granted them generation, transmission, and distribution licences. Hydel generation and water management, however, remained with WAPDA. The real watershed moment came in 2005 when KESC was financially restructured and then privatised in December 2005 with the purchase of a 71% stake in the company by a consortium of Pakistani and foreign businesses with the most prominent being Al-Jomaih Holding Company, a diversified Saudi Conglomerate, and the National Industries Group, a publicly listed Kuwaiti financial conglomerate (which also owns a large stake in Meezan Bank). However, the usual approval process and deliberation by the Council of Common Interest (CCI) did not take place prior to the sale. This is something that would rear its head for the other DISCOs over a decade later.

No progress was made for the remaining DISCOs until 2007. In November 2007, the Government of Pakistan finally notified the unbundling, separation and corporatisation of the power wing of WAPDA into Pakistan Electric Power Company (PEPCO). Earlier it was established in 1998 but remained non-functional because the Chairman of WAPDA was also the Chairman of PEPCO and in effect held the reins. Slowly, PEPCO also took over the work of appointing boards of directors to these companies and then directly took over operations of the DISCOs.

In parallel to this for three years, the Saudi-Kuwaiti conglomerate failed to make any headway in turning around the company, finally turning in 2008 to Arif Naqvi, the former Karachiite who had gone on to create Abraaj Capital in Dubai.In October 2008, Abraaj bought out half of the Jomaih-NIG stake in KESC, injecting $391 million into the company. It then began a turnaround effort the likes of which have never been seen in Pakistan before.

The subsequent metamorphosis of the DISCOs took place at the NTDC, rather than within the DISCOs themselves. In the year 2009, the Central Power Purchasing Agency Guarantee (CPPA-G) materialised as a formidable power entity, inheriting the Centre for Power Purchase Agreement (CPPA) and market development responsibilities from NTDC. However, the CPPA-G would remain in a state of dormancy until half a decade later, following the downfall of a DISCO management entity.

The residual DISCOs, in the wake of Abraaj’s acquisition of KESC, were relegated to a secondary concern as the nation grappled with a myriad of crises, and the energy sector pivoted its focus towards the independent power producers and the mitigation of load shedding. Amidst the load shedding that besieged the country, PEPCO found itself in the line of fire. The Peshawar High Court, in its suo motu action on unscheduled load shedding in 2010, decreed the dissolution of PEPCO. 2010 is also when the Sukkur Electric Supply Company (SEPCO) was carved out of the Hyderabad Electric Supply Company (HESCO) to raise the count of the DISCOs to 11.

The Cabinet of the then Prime Minister, Raja Pervaiz Ashraf, concurred with the Peshawar High Court’s decision in October 2011. The Board of Directors of PEPCO sanctioned its dissolution in 2012, and its functions were initially transferred to the NTDC and subsequently to the CPPA.

The decision to dissolve PEPCO encompassed more than just load shedding. Since PEPCO was positioned directly under the Ministry of Water and Power, which also controlled the Private Power and Infrastructure Board, the latter relinquished its independence. One rationale was that the international donor agencies simply opposed an entity to manage the DISCOs. “The International Monetary Fund and World Bank were once again engaged with Pakistan at the time. During their engagement, they stated that they did not want to create another WAPDA,” explicates Tahir Basharat Cheema, a former Managing Director of PEPCO.

The other argument was that PEPCO had degenerated into a bad WAPDA and that placing PEPCO directly under the Ministry of Energy — the policy arm of the government and not an executive implementation entity — was the main culprit for the failure of PEPCO. There were allegations of PEPCO lacking similar checks and balances or accountability akin to WAPDA’s main decision-making ‘Authority’ or its ‘Central Contract Cell’ to impartially evaluate projects and resolve all issues on merit. The Federal Government was accused of micromanaging PEPCO.

Did the DISCOs attain independence after the dissolution of PEPCO? Not in the slightest. Intriguingly, PEPCO never ceased to exist either, despite being effectively defunct. However, we’ll delve into that later in the piece.

The power crisis was one of the primary election talking points among the contenders — violent protests erupted in various parts of the country due to power outages in 2011, 2012, and 2013. Consequently, the Nawaz Sharif government that ascended to power in 2013 devised “The National Power Policy (2013)” immediately after coming into power. The revised power policy, formulated in 2013, delineated the newly elected government’s road map for the power sector. Though this policy has been lambasted for being overambitious and unrealistic, it preserved the essentials of the reform plan laid out in 1992. In addition to reaffirming the government’s focus on privatisation of the DISCOs, it also stipulated the reform of CPPA as a corporate entity separate from NTDC’s transmission and system operation business

Did the DISCOs attain independence after the dissolution of PEPCO? Not in the slightest. Intriguingly, PEPCO never ceased to exist either, despite being effectively defunct. However, we’ll come to that later in the piece.

The power crisis was one of the primary election talking points among the contenders — violent protests erupted in various parts of the country due to power outages in 2011, 2012, and 2013. Consequently, the Nawaz Sharif government that ascended to power in 2013 devised “The National Power Policy (2013)” immediately after coming into power. The revised power policy, formulated in 2013, delineated the newly elected government’s road map for the power sector. Though this policy has been lambasted for being overambitious and unrealistic, it preserved the essentials of the reform plan laid out in 1992. In addition to reaffirming the government’s focus on privatisation of the DISCOs, it also stipulated the reform of CPPA as a corporate entity separate from NTDC’s transmission and system operation business.

With the aim of privatising all the DISCOs and some generation units, the new government announced the first wave of its ambitious plan — the Lahore Electricity Supply Company (LESCO), the Islamabad Electricity Supply Company (IESCO), and the Faisalabad Electricity Supply Company (FESCO) were among the chosen ones. To kick-start the privatisation campaign, the government launched a nationwide anti-theft drive that involved the provincial and the federal bureaucracy, and spanned from 2013 to 2014. Perhaps the most intriguing initiative during the drive was the Peshawar Electric Company’s (PESCO) advertisement in newspapers that appealed to the religious sensibilities of the consumers in an attempt to curb theft. It was also in 2014 that KESC rebranded itself as K-Electric.

The commercial operation of CPPA-G commenced in mid-2015 after the transfer of functions between NTDC and CPPA-G were finalised and completed. What was the significance of the CPPA, NTDC, and CPPA-G in this context? The CPPA-G was supposed to create a competitive market for electricity in Pakistan, whereby the DISCOs could purchase from any supplier they wanted. It would be the next step in their autonomy. Did it materialise? Not in the slightest. The DISCOs remained under state control, so the blame could not be solely attributed to the CPPA-G.

2015 bore witness to mounting legal pressure against the manner in which K-Electric was privatised, and the effectiveness of privatisation was called into question. Political and economic apprehensions led to the abandonment of the privatisation plans. These concerns stemmed from the government’s scepticism that the previous privatisation experience with KE had not yielded the anticipated outcomes of reduced subsidy burden and enhanced service delivery to the end-users. Nevertheless, the incumbent government managed to make one last significant decision regarding the separation of the DISCOs. In 2017, a distinct Ministry of Water Resources was established, and WAPDA was placed under its jurisdiction, while all aspects of power were transferred to the Ministry of Energy (Power Department).

As the 2018 election year approached, political opposition from other parties and the workers’ union intensified. Consequently, the government altered the privatisation mode for LESCO and FESCO from strategic sale to gradual divestment through capital markets. This process was anticipated to span the next three to five years. However, as the election loomed large, the government shelved any discussion of privatisation, leaving the future of the energy sector in a state of suspense.

What was the strategic blueprint of Imran Khan’s administration to grapple with Pakistan’s vexing DISCOs upon seizing the reins of power? The answer lies in yet another campaign against theft. The nascent administration dedicated the entirety of 2019 to the relentless pursuit of this anti-theft initiative. Concurrently, the government revisited the concept of privatisation, as it embarked on a mission to rejuvenate Pakistan’s PEPCO for centralised supervision and regulation of all ten public DISCOs — a preliminary step towards a reform agenda that could potentially culminate in their privatisation.

According to the scheme, PEPCO was to function as the ‘Management Agent’ for all the DISCOs, through a Management Agent Agreement — endorsed by the pertinent boards of directors — to aid the Privatisation Commission or any other entity or department in executing the government’s privatisation blueprint, and to evaluate and propose alternative methods of relinquishing the ownership of these autonomous corporate entities.

In the subsequent year, 2021, PEPCO underwent a rebranding exercise and emerged as the Power Planning and Monitoring Company (PPMC). The company’s headquarters were translocated from Lahore to Islamabad, and it ultimately amalgamated with the Ministry of Energy. Regrettably, no further progress was made during Imran’s tenure, as political upheaval, a recurring theme by then, once again took centre stage.

Back to the future

The past eighteen months have arguably been the most tumultuous for the DISCOs, as the Shahbaz Sharif and Anwar Kakar governments proposed every possible measure to improve the DISCOs. The former advocated provincialisation and privatisation, while the latter suggested handing over the Hyderabad Electric Supply Company to the Army — yet again. The current government is also mulling over awarding professional managerial contracts. Coincidentally, at the time of writing, the Ministry of Energy is conducting another anti-theft campaign. This is the fourth such campaign since the DISCOs came into being less than a quarter of a century ago.

The only noteworthy development that has occurred since 2022 until now is that the Hazara Electric Power Company (HAZECO) has been split from PESCO, increasing the total number of DISCOs to 12. Furthermore, K-Electric went through another spell of ownership change which we have covered in detail earlier this year.

Read more: Who is Shaheryar Chishty and what does he want with K-Electric?

What is with the overcharging?

Now, let us return to where we began. Overcharging. How does it operate? How severe is it? The essence of the matter is that metre readers essentially recorded electricity consumption readings exceeding 30 days and billed them as a 30-day bill. Is this detrimental? It depends.

“The DISCOs do overbill due to various reasons — legiimatet or otherwise. However, it is usually rectified in the subsequent month. Suppose that you received a bill of 110. If next month your reading is for 200 units, then they will adjust it. Therefore, to assert that the DISCOs have overbilled customers to enrich themselves may be erroneous but surely it is done to culture poor results. That is not how it works,” explains Cheema.

“The problem emerges when a customer’s slab is altered, and they are charged a higher rate than they would have otherwise. People who experienced a change in their slab due to the overbilling have been wronged. There is no question about that,” Cheema adds.

What does all this imply? Let us do some simple arithmetic. At 290 units, an individual’s bill would have amounted to 10,730. If you were to charge them 20 units extra and they fall into the 300 slab, their bill would have soared to Rs 13,330. Because the slab is different up to 300 units. The rate up to 300 units is Rs 37. When it goes above 300, then all the units have to be charged Rs 43. You have directly inflicted a loss of roughly Rs 4,000 on a consumer.

So, will the DISCOs be penalised for this error? Unlikely, the Ministry of Energy is currently conducting its own investigation as to the validity of NEPRA’s report. Is NEPRA’s report correct? Likely, but not because NEPRA is very good but because the DISCOs have done this numerous times before.

So, why does a DISCO do this? And more importantly, is there any way to fix the 100 year mess that we’ve just read about?

Why are our DISCOs the way they are

Let us begin with the most fundamental of things. DISCOs have no need to overcharge customers to compensate for their losses.

“Exorbitant pricing is not a sustainable solution. A more fitting approach would be to perpetually monitor areas with high theft trends and conduct regular meter inspections and kundas. Furthermore, in areas with high technical losses, the conductors and transformers could be replaced. It’s crucial to note that electricity theft is not the sole contributor to a DISCO’s losses; wastage of electricity due to inadequate infrastructure also plays a significant role,” elaborates Shahid Iqbal Chaudhry, a former Chief Executive of IESCO.

So, one might wonder, why would a DISCO resort to such measures? It’s undeniably unethical. The answer lies in a labyrinthine escalator with multiple exits.

“Malpractice within a DISCO is akin to a ladder, ascending from a meter reader to upwards. If, at any stage of this cycle, appointments are made based on criteria other than merit, then such an outcome is inevitable,” Chaudhry expounds. However, this is merely the tip of the iceberg. There exists a more flagrant reason.

“Our DISCOs are akin to uncontrolled kites, adrift in the wind. The negligence originates from the top. The Ministry of Energy, the overseers of the DISCOs, and the boards they appoint as administrators, are at the helm. If the problem is to be rectified, they must acknowledge their blunder and heads must roll,” Cheema asserts with conviction.

Quite straightforward, indeed.

So, how does one rectify the DISCOs? The succinct answer is that there is no definitive answer. There is a semblance of consensus during our discourse in penning this narrative that the optimal time to rectify the DISCOs was when they were a part of WAPDA. The next best time was when PEPCO wielded some authority. The best time now? It might vary from DISCO to DISCO.

Let’s scrutinise each potential solution, and subsequently discuss why it might not be feasible. Let’s start with privatisation.

“K-Electric, despite all its negative criticism, some of which is indeed valid, provides a blueprint for the DISCOs. It’s not a flawless blueprint, but it’s a model that doesn’t contribute to our circular debt,” Khan explains. The issue with privatising the DISCOs is that not everyone covets all the DISCOs. The Punjab-based DISCOs and IESCO might pique the interest of a buyer. The others may not, due to their financial predicament and because they cater to customers with considerably lower purchasing power. They cater to far fewer industrial customers and they operate in areas that are generally perceived to lack the rule of law relative to Pakistan’s larger urban areas. All of this does not paint an enticing image for any private investor.

What is another solution? Some form of provincial accountability. “If the DISCOs are incapable of curbing the rampant theft, they must be relinquished to the provinces. The provinces will remain oblivious to the magnitude of the issue as long as the circular debt is a federal responsibility. In the event that the provinces are unable to bear the entire burden, perhaps they should be held accountable for the additional losses that the energy infrastructure incurs due to theft specific to their province,” Chaudhry expounds.

Chaudhry’s proposal deserves some consideration. Given that the police falls under the jurisdiction of the provincial government, and that theft cannot be curbed without the participation of law enforcement, it seems logical to align the interests of the provinces. However, the predicament here is that the provinces are already struggling with self-management.

Expecting those components of Pakistan’s federation, who are unable to efficiently run their own healthcare and education systems, to oversee a colossal DISCO and its losses is akin to throwing the baby out with the bathwater. This is not to imply that it’s fair for customers based in Punjab and Islamabad to endure higher electricity tariffs due to the tariff rationalisation surcharge that subsidises those DISCOs customers where theft is rampant. But concurrently, does anyone want to ignite a provincial rights crisis in addition to the energy crisis?

Is there another solution? “The remedy to this is to award its management contracts to the financial entity that possesses the financial depth and brings the best technical or professional team,” Cheema expounds. While accurate, the question remains: will any management team be willing to serve the DISCOs if they do not have a long-term vested financial stake in it? How would any management contract differ from merely hiring a regular consultant? This is the approach we have adopted for other governmental departments with varying degrees of success. Some state-owned enterprises even boast boards of directors that rival the best companies in the private sector, yet they lack the outcomes to show for it. Some state-owned companies even employ individuals from the best private sector companies but fail to deliver the results.

Do you want to know the cherry on top? There’s a chance that the DISCOs might never be rectified. “The distribution business is not profitable in Pakistan. K-Electric is able to maintain its profitability from its generation business, not its distribution business. When WAPDA was a singular entity, it did the same. Distribution companies cannot turn a profit as long as electricity in Pakistan is subsidised,” Khan clarifies. Remember that unified tariff? The best part is that it cannot be reversed, at least not easily.

“The unified tariff should have been abolished by now. The only opportunity that existed to remove it was when WAPDA was first de-bundled. You cannot feed people cake for so long, and then expect them to revert to bread,” Chaudhry explains. “As a first step regional regulators should be enacted to decide distribution tariff. The province unhappy with higher tariffs ‘based on high loss of their area’ may pick up the difference,” Chaudhry continues.

So, how do you rectify the DISCOs? The optimal approach would be to experiment with all three aforementioned solutions on different DISCOs, and observe what works. Pakistan’s electricity infrastructure has been trapped in a vicious cycle since its inception. The DISCOs do not face novel problems. We are not devising new solutions. It has been the same problem since day one, and everything done to fix it is the best example of a truck ki batti that the country could have.

Highly Recommended!

Very insightful, i will also say this here. Investment is one of the best ways to achieve financial freedom. For a beginner there are so many challenges you face. It’s hard to know how to get started. Trading on the Cryptocurrency market has really been a life changer for me. I almost gave up on crypto at some point not until saw a recommendation on Elon musk successfully success story and I got a proficient trader/broker Mr Bernie Doran , he gave me all the information required to succeed in trading. I made more profit than I could ever imagine. I’m not here to converse much but to share my testimony; I have made total returns of $10,500.00 from an investment of just $1000.00 within 1 week. Thanks to Mr Bernie I’m really grateful,I have been able to make a great returns trading with his signals and strategies .I urge anyone interested in INVESTMENT to take bold step in investing in the Cryptocurrency Market, you can reach him on WhatsApp : +1(424) 285-0682 or his Gmail : BERNIEDORANSIGNALS@ GMAIL. COM bitcoin is taking over the world, tell him I referred you