There is a lot of talk about climate financing in Pakistan. The floods of 2022 and the ensuing attention Pakistan has gotten at COP27 and COP28 have made it clear that there is a dire need for some sort of monetary interventions to help fix the climate crisis.

But many have felt that the focus over the years has been more on financing on a government level from international agencies. There is some point to this as well. The Global North has disproportionately contributed to the pollution of the Global South and there are many advocates for climate reparations. The process is slow and unreliable however.

In its place there are arguments that climate financing should come from the private sector. That there should be projects, startups, and initiatives that are green in nature and they should have funding readily available. This would create a bit of a two-birds-one-stone situation: You save the environment and make money doing so.

In this sense, one noteworthy advancement in the realm of climate change adaptation has occurred in the country recently. Acumen Pakistan has secured a $28 million anchor funding for a new $90 million Climate Fund targeting the agriculture sector in Pakistan. The initiative is structured as an innovative blended finance facility, with $80 million in equity funding allocated for early and growth-stage local agribusinesses. An additional $10 million will be used for grant funding to offer targeted assistance in enhancing the business models of investee companies and bolstering the overall climate resilience of the ecosystem in Pakistan.

While the project is being hailed as a milestone in the country’s push against climate change, the question remains: can it live up to its promise?

The climate challenge

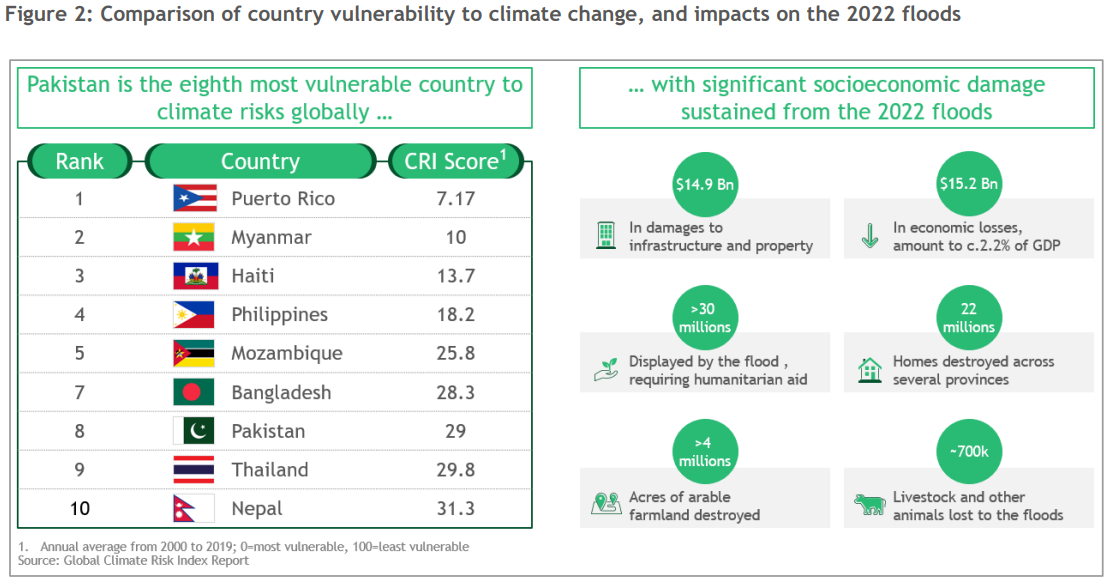

Pakistan is facing increased vulnerability to the impacts of climate change. The nation is already experiencing tangible effects like droughts, floods, and melting glaciers, putting it among the top ten most vulnerable countries to climate change. To tackle these challenges, Pakistan introduced the National Climate Change Policy (NCCP) in 2021.

Perhaps nothing encapsulates the depth of this problem like the floods Pakistan witnessed in 2022 and is still partially reeling from two years on. All in all, according to the latest report of the Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA), Pakistan needs at least $16.3 billion for post-flood rehabilitation and reconstruction. The PDNA report, released by the representatives of the government and the international development institutions, calculated the cost of floods at $30.1 billion – $14.9 billion in damages and $15.2 billion in losses.

But there are catches to this as well. Pakistan is supposed to cut down on its own emissions and meet certain standards. As a signatory to the 2015 Paris Agreement, Pakistan aligned its first Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) with sustainable development goals and aimed to reduce 20% of projected emissions by 2030, necessitating around $40 billion. Subsequently, updated NDCs were agreed upon.

The country has now set a target of a 50% reduction in projected carbon emissions from 2015 to 2030, with 15% coming from Pakistan’s resources and 35% from international financial support. Achieving this goal involves implementing climate mitigation and adaptation actions in sectors such as energy, transportation, waste, and agriculture.

The country has now set a target of a 50% reduction in projected carbon emissions from 2015 to 2030, with 15% coming from Pakistan’s resources and 35% from international financial support. Achieving this goal involves implementing climate mitigation and adaptation actions in sectors such as energy, transportation, waste, and agriculture.

Adaptation involves making adjustments to cope with the effects of climate change, such as building seawalls to protect against sea-level rise. Mitigation, on the other hand, focuses on reducing greenhouse gas emissions to prevent further climate change, for example, transitioning to renewable energy sources.

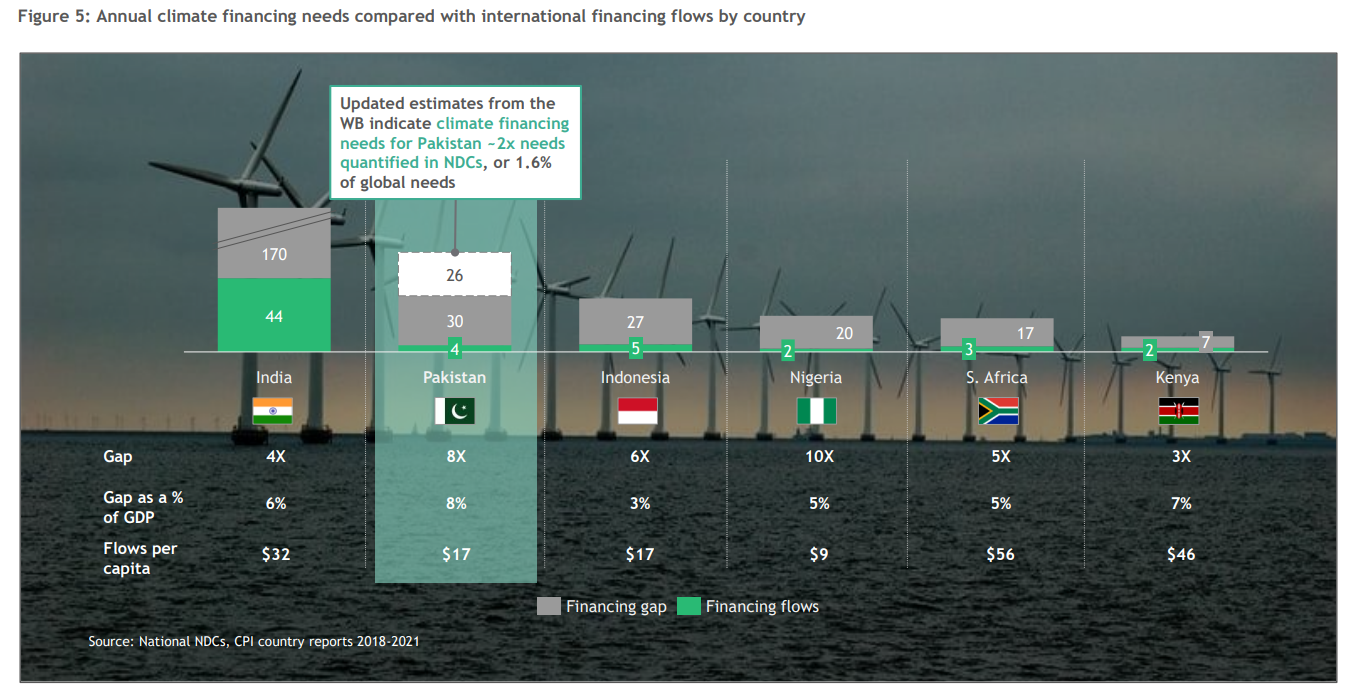

The need to address the financing gap

According to the Word Bank’s research cited in the Accelerating Green and Climate Resilient Financing in Pakistan report by UK International Development, “total investment required for a comprehensive approach to Pakistan’s climate challenges from 2023 to 2030 is estimated at $348 billion (equivalent to 10.7% of cumulative GDP for the same period). This includes $152 billion (44%) for adaptation and resilience and $196 billion (56%) for decarbonisation. This amount significantly surpasses the historical average annual development budget at the federal and provincial levels.”

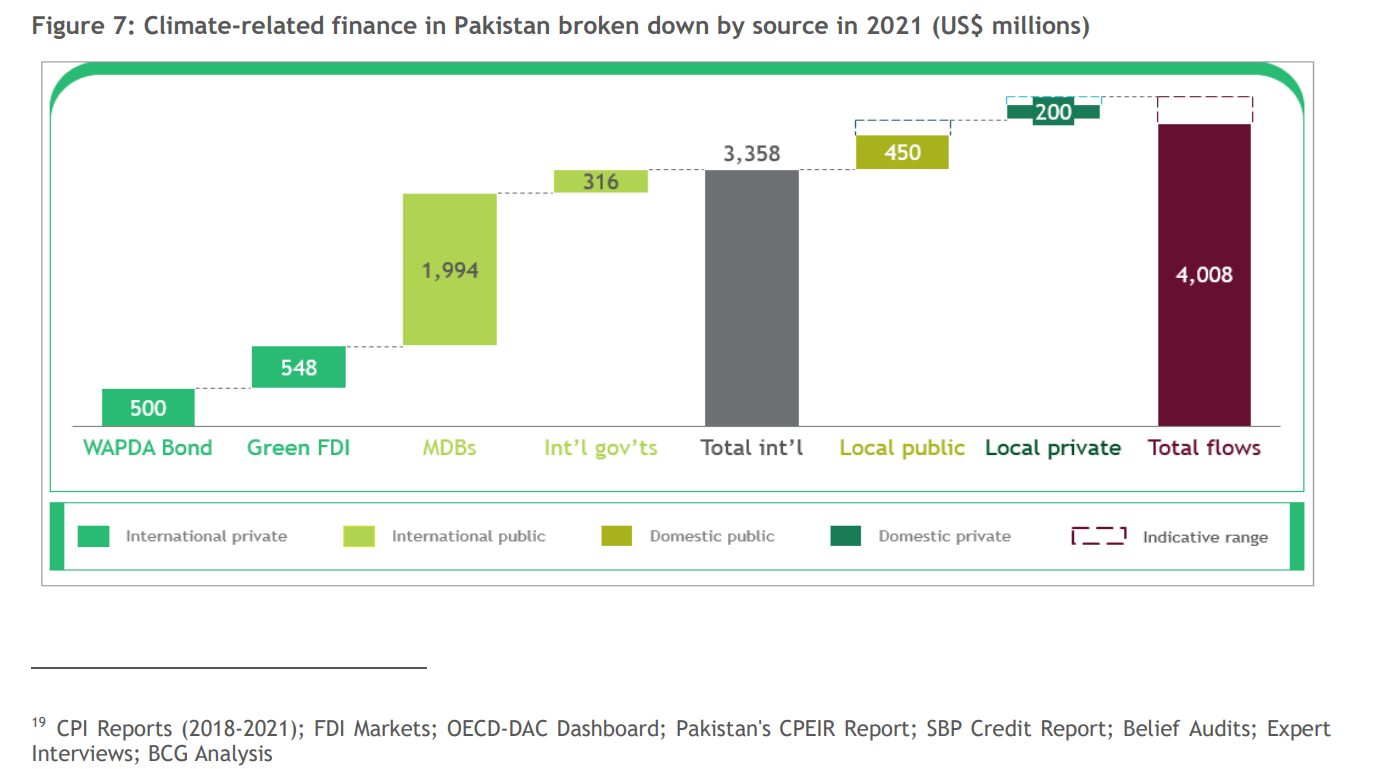

The report revealed that in 2021, a total of $4 billion in climate-related investments were made in Pakistan, sourced from both domestic and international channels. Private sector contributions made up 31% of the total investment, while the public sector accounted for the remaining 69%.

Clearly the public sector is leading in this sense. But what is the exact breakdown? Around $650 million domestic funding came from local sources for example which accounts for 16% of this funding, with public and private sectors contributing 11% ($450 million) and 5% ($200 million) respectively.

International actors played a significant role, providing 84% ($3,358 million) of the total climate finance, with Development Partners contributing 58% ($2,310 million). Moreover, international private sector investors and project developers contributed 26% ($1,048 million) of the total financing.

Despite the country’s pressing climate vulnerabilities, there was a disproportionate focus on mitigation rather than adaptation and resilience financing in Pakistan. Mitigation efforts accounted for 79% ($3,147 million) of the financing, with substantial investments in renewable energy generation, totalling $2,020 million, primarily facilitated through the State Bank of Pakistan’s renewable energy financing initiative.

The evident gap in raising domestic financing originates from the relatively nascent green finance market in the country, where traditional financing institutions often lack the expertise and mechanisms to evaluate climate projects effectively.

The evident gap in raising domestic financing originates from the relatively nascent green finance market in the country, where traditional financing institutions often lack the expertise and mechanisms to evaluate climate projects effectively.

Additionally, a perception of high risks associated with climate initiatives contributes to local financiers’ reluctance to invest in such projects. Limited public awareness and understanding of the benefits of climate financing further hampers local financial support for these initiatives.

Challenges in accessing affordable long-term capital and the absence of tailored financial products for climate projects adds to the overall scarcity of local funding options in Pakistan.

Furthermore, the cash-strapped government has limited fiscal space due to the burden of debt servicing, which constrains its ability to finance climate-related projects.

What does the fund do differently?

Acumen’s new initiative aims to provide catalytic funding to a targeted audience. In this case it is for the agriculture sector. The goal is increasing local capacity and building the climate resilience of millions of smallholder farmers while attracting private capital towards national climate adaptation priorities.

Agriculture remains one of the most vulnerable sectors in the country with regards to the effects of climate change. This vulnerability is compounded by the sector’s status as the largest employer in the country.

Small-scale agribusinesses in Pakistan struggle to raise finance due to limited access to formal financial institutions, insufficient collateral, high-interest rates, perceived risks in agriculture, and lack of financial literacy. Additionally, their seasonal and unpredictable nature makes it difficult to secure stable financing.

“We believe that this first-of-its-kind climate fund will serve as a paradigm-shifting model for Pakistan,” remarked Dr. Ayesha Khan, Regional Director for Acumen in Pakistan

“By channeling investments into innovative agribusinesses, we will not only unlock financing for a critical sector but also empower those who bear the brunt of climate catastrophes,” she added.

The initiative is supported by the Green Climate Fund (GCF), which is the world’s largest dedicated climate fund and the primary multilateral financing mechanism for developing countries such as Pakistan in addressing climate change.

| GCF financing | |

| Instrument | Amount $M |

| Equity | 25 |

| Grant | 3 |

| Total GCF Financing | 28 |

| Co-Financing | |

| Instrument | Amount $M |

| Equity | 55 |

| Grant | 7 |

| Total Co-Financing | 62 |

| Total | 90 |

GCF’s contribution of $25 million equity is supplemented by targeted co-financing of $55 million. Impact funds like the one initiated by Acumen operate on the principle of providing funding at below-market rates or with more flexible terms to support projects that may not be feasible or economically viable under traditional market conditions.

“The fund has a 10-12 years time horizon with anchor funding already approved by GCF. The junior equity provided by GCF serves as a significant de-risking factor, offering first-loss cover and attracting interest from more commercially oriented impact investors to invest in senior equity,” Dr. Ayesha Khan told Profit.

While commenting on specific avenues for private financing, she added, “Given Pakistan’s macroeconomic condition, mobilizing interest from international investors is quite challenging. Even some local corporations are divesting. Therefore, the current focus of fundraising is on international impact investors who view Pakistan as a deserving recipient of funds to address the impact of climate change.”

However, climate impact funds face several limitations in achieving their intended objectives. These include challenges related to scalability, as limited funding and resources may hinder their ability to address climate challenges on a large scale.

Additionally, measuring the true impact of climate investments can be complex and subject to variability across projects and sectors. Climate projects often require long-term commitments and stable funding, which can be difficult to sustain over extended periods.

However, this is not uncharted territory for Acumen. The U.S.-based nonprofit has previously launched an agri-focused fund called the Acumen Resilient Agriculture Fund (ARAF) in Africa, also supported by GCF.

ARAF’s structure, similar to Acumen’s Pakistani fund, incorporates GCF’s anchor investment of $23 million in equity in ARAF’s first loss pool. This structure is catalytic as it de-risks the investment for risk-averse private sector investors. This funding provides protection from what many investors often consider as the high risks associated with financing early-stage agribusinesses and services for small-scale farmers.

“ARAF closed the fund on 30th June 2021 leveraging GCF’s investment by over 2.5x. The Fund together with other investors has made eight equity and quasi-equity investments in Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria and Ghana as of December 2022. ARAF’s investments have attracted an additional 4.49x in co-investments into existing portfolio companies,” read the Fund’s 2022 annual report.

While Khan aims to achieve similar or even better results, the augmented sector risk in Pakistan’s agricultural domain poses a significant challenge. Navigating this and achieving agreed-upon levels of profitability over the next ten years is a mountain that needs to be climbed, and Acumen appears to have accepted the challenge.

The world must support Pakistan for climate fund as its worst-affected country in the world by climate changes.