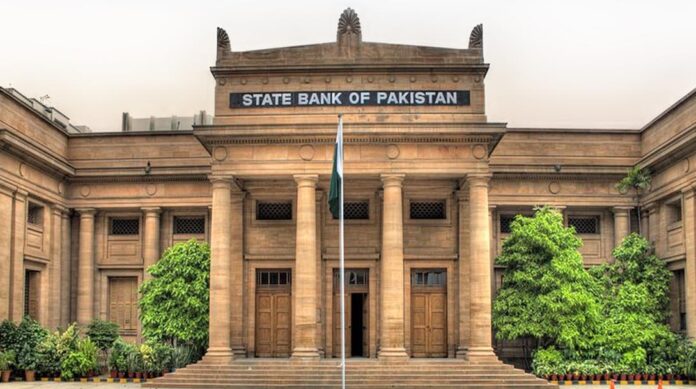

The Government of Pakistan is currently experiencing an unprecedented surge in liquidity, both domestically and in its international reserves. This favorable position is partly due to the International Monetary Fund’s recent disbursement of a $1 billion loan tranche. More notably, the local liquidity situation received a significant boost from a record Rs2.7 trillion dividend announced by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP).

This substantial dividend was made possible by the central bank’s extraordinary profit of Rs3.4 trillion, marking a staggering 200% increase from the previous year. The root of these enormous figures lies in the SBP’s generous lending to financial institutions at record interest rates through open market operations.

Ironically, most of these funds were subsequently invested in government securities at even higher rates, creating a circular arrangement where the government of Pakistan essentially enabled its own profitability and is now reclaiming the same funds.

While the focus of this article is not to critique this unconventional arrangement, it aims to elucidate the sequence of events leading to the buyback and its future implications. The stage for higher dividends was set during last month’s post-MPC analyst briefing when the SBP governor hinted that the government’s share of SBP’s profits would likely exceed budgeted expectations.

This prediction materialized in the form of the Rs2.7 trillion dividend, providing the government with a temporary liquidity surge, which it promptly utilized to announce a buyback of its securities.

The first of what may be a series of buybacks occurred last week, with the SBP intending to repurchase Rs500 billion of T-bills but ultimately securing Rs351 billion worth. This context leads us to a crucial question: Why is the government suddenly so keen on buying back its own securities? The content in this publication is expensive to produce. But unlike other journalistic outfits, business publications have to cover the very organizations that directly give them advertisements. Hence, this large source of revenue, which is the lifeblood of other media houses, is severely compromised on account of Profit’s no-compromise policy when it comes to our reporting. No wonder, Profit has lost multiple ad deals, worth tens of millions of rupees, due to stories that held big businesses to account. Hence, for our work to continue unfettered, it must be supported by discerning readers who know the value of quality business journalism, not just for the economy but for the society as a whole.To read the full article, subscribe and support independent business journalism in Pakistan