ISLAMABAD: Pakistan’s apparel industry is under increasing strain as climate change intensifies, significantly impacting production and worker conditions.

A December 2024 policy brief by the Cornell Global Labor Institute (GLI) reveals that rising temperatures and unpredictable flooding are among the most pressing challenges.

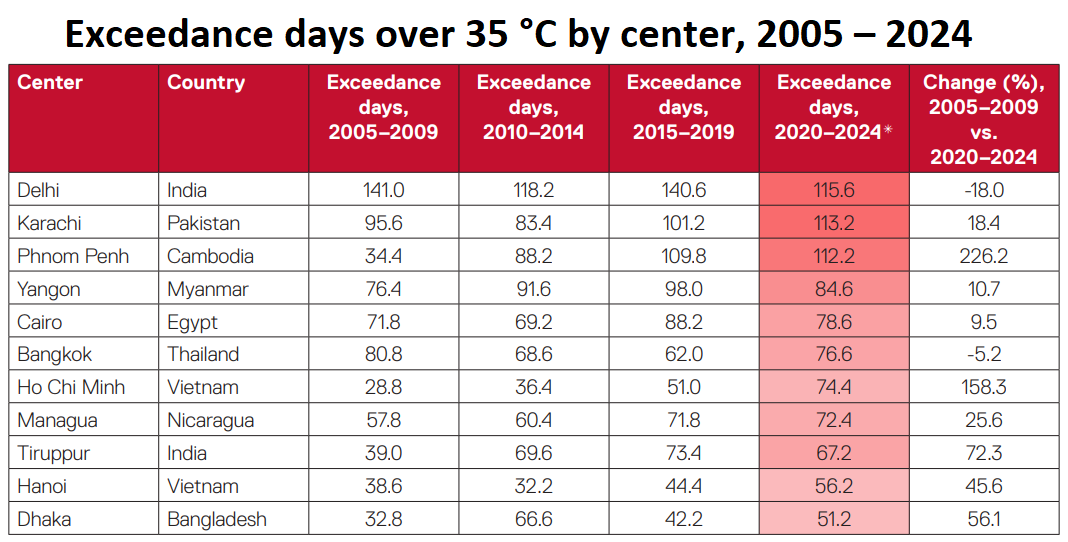

Karachi, a major manufacturing hub, recorded 115 wet-bulb heat stress days in 2020, marking a peak in an upward trend that has been evident over the past two decades. Between 2005–2009 and 2020–2024, the city experienced an 18.4% rise in days where temperatures exceeded 35 °C.

July 2024 brought severe heatwaves, causing power outages and water shortages in Karachi, prompting the government to extend summer holidays by two weeks for over 100,000 schools.

The escalating climate risks are not unique to Pakistan. The report outlines that Bangladesh, Cambodia, and Vietnam also could face a 22% reduction in nominal earnings from the apparel sector by 2030 without climate adaptation measures. This would result in nearly one million new jobs being foregone.

By 2050, these losses could deepen to 68%, with eight million jobs disappearing across these countries.

The report identified only three retailers – Nike, Levi’s, and VF Corp – which specifically include protocols to protect workers from heat exhaustion in their supplier codes of conduct.

Pakistan’s Factories Act of 1934, mandates essential measures to mitigate heat stress in workplaces, emphasizing worker safety and comfort. Section 15 of the Act requires factories to maintain adequate ventilation, ensure a continuous supply of fresh air, and regulate temperatures to prevent health risks.

Building materials for walls and roofs must minimize heat retention, while additional measures, such as insulating hot machinery and separating high-temperature processes from workspaces, are required to protect workers.

In India, factory workers in Tamil Nadu reported widespread heat-related illnesses. Conditions inside factories were described as unbearably hot, with insufficient measures taken to mitigate the effects of extreme heat.

Similarly, Cambodia and Thailand reported excessive indoor heat disrupting worker routines and health.

Bangladesh, one of the world’s largest garment producers, witnessed 42 wet-bulb heat stress days in 2024. The extreme conditions led to school closures affecting 33 million children and significantly reduced productivity among garment workers, with many falling ill and taking extended sick leave.

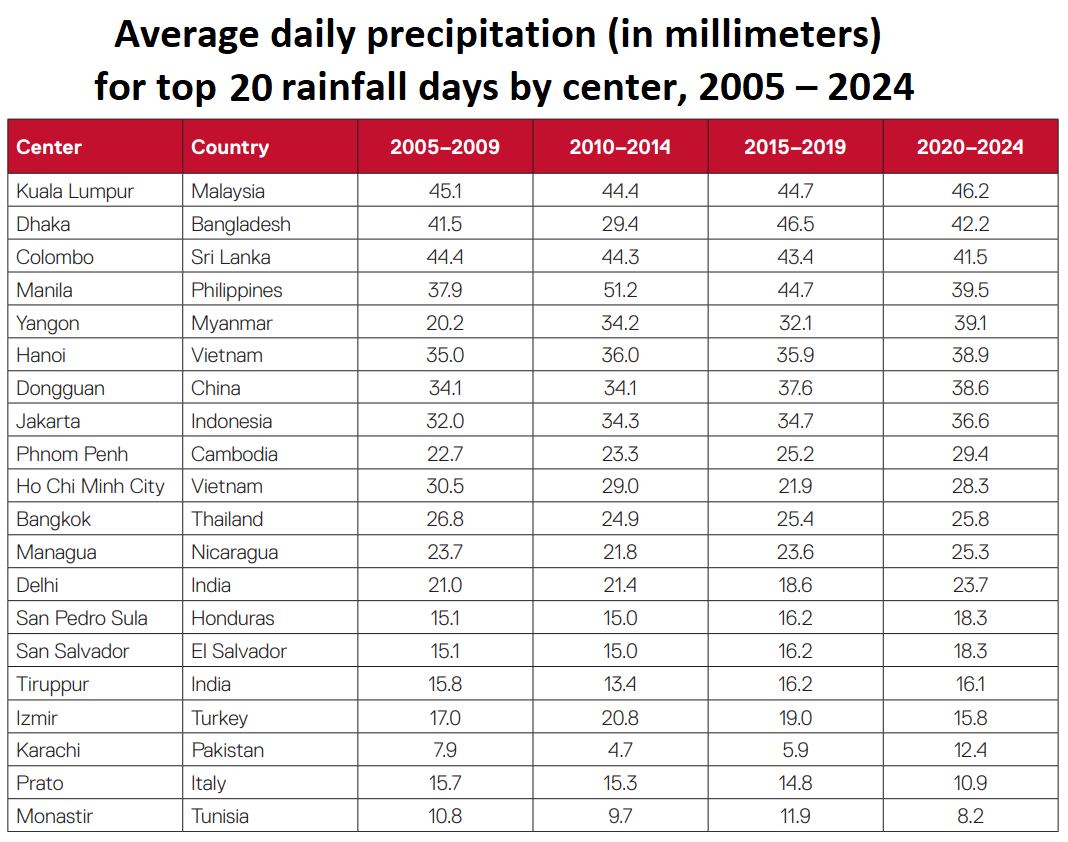

Bangladesh also faced devastating floods in August 2024, which disrupted supply chains and slowed operations at the critical Chattogram port.

The GLI report highlights that while Pakistan’s Sindh Province has guidelines on maintaining reasonable conditions of comfort in factories based on wet and dry bulb readings, these measures are insufficient compared to other nations.

Vietnam’s standards include precise temperature thresholds for different levels of work effort, while Malaysia enforces detailed heat stress management systems.

Vietnam is another country grappling with the consequences of climate change. Ho Chi Minh City experienced a marked rise in heat waves, forcing workers to take shelter under city bridges.

Flooding and power outages compounded the challenges in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh, further impacting garment production.

In Karachi, flooding risks remain volatile, with average daily precipitation rising to 12.4 mm in 2020–2024 from 5.9 mm in 2015–2019. Such climatic unpredictability exacerbates production delays and worker vulnerabilities.

Extreme heat and flooding could erase $65 billion in apparel export earnings from Bangladesh, Cambodia, Pakistan and Vietnam by 2030, research from asset manager Schroders and the Global Labor Institute found last year.

The report calls for urgent investments in climate adaptation measures, including workplace cooling systems, enhanced labor protections, and robust social safety nets. These steps are crucial to mitigating the economic and human costs of climate change.

Without such measures, the apparel industry in Pakistan and its regional peers faces prolonged disruptions, reduced productivity, and significant job losses. The GLI emphasizes that these investments are not only necessary for protecting workers but also essential for sustaining the global supply chain and mitigating long-term economic risks.