Statistics can tell you the truth, but only if you know what you are looking for. Statistically speaking, airline travel is one of the safest forms of travel in the world. According to The Economist, the odds of an individual passenger being in a plane crash are about 1 in 5.4 million. For context, you are about five times more likely to be struck by lightening than be in a plane crash.

And even if you do go down in a plane crash, the odds of surviving a plane crash are about 95%, according to data from the United States National Transportation Safety Board. (That is because most plane crashes are minor events that do not get reported on. Only the major ones, with mass casualties, make the news.)

But all of those are aggregates. What were the odds of an individual passenger surviving the crash of Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) flight 8308, from Lahore to Karachi, which crashed on May 22, 2020? Of the 12 “non-survivable” plane crashes that have taken place in Pakistan since 1988, 742 of the 744 passengers on board those flights have been killed. Only two – both on Flight 8308 – have survived. The probability of surviving a major plane crash in Pakistan, then, is a vanishingly slim 0.27%.

Zafar Masud, the President and CEO of the Bank of Punjab, is one of those two, the miracle man who somehow survived the crash that killed 97 other people. It is unlikely that he was thinking of any of these numbers when the plane went down, but he appears to be very much aware of just how lucky he is to have survived the crash.

This story, however, is not about his crash. It is about him as the new man at the helm of the Bank of Punjab, the country’s largest provincial government-owned bank, and one that barely survived the financial crisis of 2008. And it is about the Bank of Punjab as an institution that has managed to overcome the odds and become one of the few government-owned institutions that has recovered from a near-bankruptcy experience – albeit with heavy government interventions and relaxations of rules not available to other financial institutions, and a massive multi-billion-rupee taxpayer-funded bailout.

Why the Bank of Punjab exists

All four provincial governments in Pakistan have owned a bank at one point or another, but the trend of provincially owned banks started with the Bank of Punjab. In 1989, the government of Punjab, under then-Chief Minister Nawaz Sharif, decided to create a bank and named it the Bank of Punjab.

(Incidentally, it was not the first time Lahore-based bank named the Bank of Punjab had been created. A bank with the same name had been created in 1936, but it moved its headquarters in 1947 from Lahore to Panipat, in what was then Indian Punjab, and what is now in Haryana. The financial crisis that was precipitated by Partition will be the subject of future stories in Profit.)

Until that point, the only government that had owned banks in Pakistan was the federal government. But in the late 1980s, as Pakistan got its second taste of multi-party democracy, the government of Punjab decided to experiment with the creation of a financial institution that could take advantage of the financial heft of the bank deposits of the country’s largest provincial government, and in turn utilise those deposits towards the achievement of the provincial government’s policy goals.

The bank’s establishment, however, ended up taking five years as the political battles of the early 1990s prevented progress on creating the bank. It was not until 1994 – under then Chief Minister Manzoor Ahmad Wattoo – that the Bank of Punjab was finally granted scheduled bank status by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP).

By that time, other provincial governments started creating their own banks as well. The Bank of Khyber – owned by the government of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa – was created in 1991 and Bolan Bank – owned by the government of Balochistan – was established in 1992. (Sindh was the late bloomer, not establishing Sindh Bank until 2010.)

The problem with a bank owned by a provincial government was exactly what one would expect: businesses that were well-connected with the chief minister could get access to loans in contravention of prudent lending policies at the bank. And that is exactly what happened in the case of the Bank of Punjab under the Musharraf Administration, when Chaudhry Pervaiz Elahi was the chief minister.

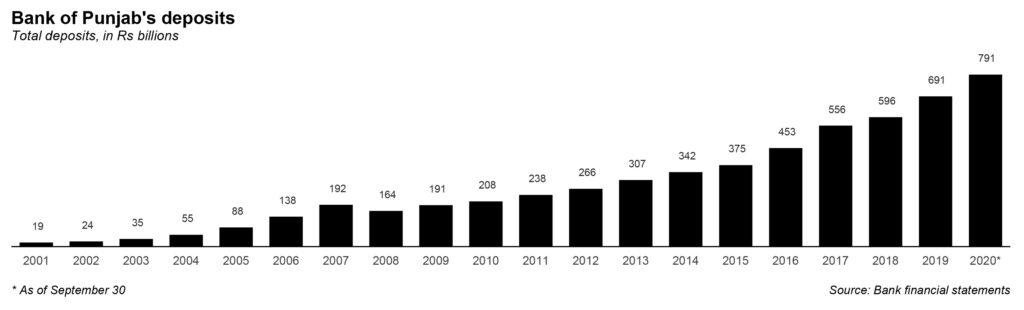

They were the golden years of banking in Pakistan, but even by boom-time standards, growth at the Bank of Punjab was stellar. Between 2002 and 2007, the bank’s deposits grew from Rs24 billion to Rs192 billion, representing an average annual growth rate of 51.9%, compared to the industry’s average growth rate of 18.3% per year.

But, of course, the growth was built on a mirage. The bank’s growth had come in part due to broader economic growth and the growing financial heft of the Punjab government, but also because it raised high-cost deposits from the private sector – both financial institutions as well as companies – and lent it out, in far too many cases, to politically well-connected businesses.

A particularly egregious case was that of Haris Steel, which despite being a relatively small steel mill was somehow able to borrow Rs9 billion – way beyond their credit limit – through a combination of fraud and connivance with bank officials, allegedly including then Bank of Punjab President Hamesh Khan, who left the job in 2007 and fled the country citing fear of political victimisation when the allegations first surfaced.

Hamesh Khan was even extradited from the United States – the first time that the US has ever extradited a fugitive to Pakistan – to face charges of mismanagement and corruption. The hole in Bank of Punjab’s balance sheet, however, suggests that the problem was much wider than the Rs9 billion loan to Haris Steel.

The post-2008 clean up

The full scale of the problem at the Bank of Punjab did not become clear until 2008, when the massive financial crisis that hit the world and Pakistan coincided with a change in political administration in Punjab, and a return of the Sharif family at the helm of the provincial government in Lahore. Nawaz’s brother Shehbaz became chief minister of Punjab in June 2008, a position he would hold almost uninterrupted for the next 10 years until June 2018.

For most of 2008, the Bank of Punjab did not have a full-time CEO, until September 2008, when Naeemuddin Khan, a veteran banker, was appointed president by the Punjab government.

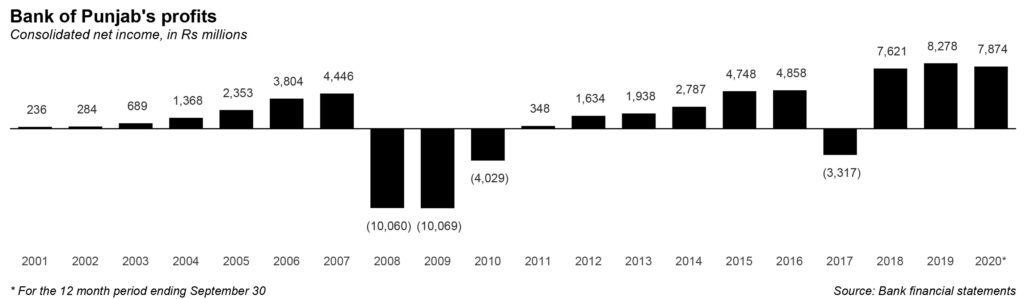

At that point, the scale of the damage to the Bank of Punjab’s balance sheet was so huge that the bank did not release its financial statements for a full three years while the provincial government and the State Bank worked out an agreement that would allow the bank to continue functioning without having to declare bankruptcy.

It was unnerving that even though the Punjab government announced a Rs10 billion taxpayer-funded bailout of the bank in 2009 and another Rs10 billion taxpayer-funded bailout in 2010, the Bank of Punjab was still not able to release its financial statements, leading the entire financial services industry to wonder just how bad it was at the bank.

During that time, the Bank of Punjab was effectively shunned in the interbank lending market, which is where banks lend money to each other to manage their day-to-day cash requirements. While other banks are typically able to borrow money purely on the strength of their reputations and creditworthiness, during the four years between 2008 and 2012, the other banks used to require the Bank of Punjab to post government bonds as collateral before they would lend money to it. And even then, only up to 98% of the value of the bonds.

In March 2012, the Bank of Punjab finally came clean. It issued its financial statements for the four years from 2008 through 2011, and for the first time, the country’s financial services sector was able to see the full scale of the problem. The bank disclosed for the first time that it had booked loan losses of Rs19.2 billion, Rs10.2 billion, and Rs3.3 billion in the years 2008, 2009, and 2010 respectively. For context, the total amount of loans that the bank had given out as of December 31, 2007 – before the scale of the crisis became known – was Rs134 billion.

But here is the scarier part: hidden away in Note 1.2 of the bank’s financial statements for 2011 was an even more unnerving bit of data. Despite having booked Rs32.7 billion worth of loan losses over three years, the bank stated that it still had another Rs33.1 billion in bad loans for which the State Bank of Pakistan had granted it a special exemption: that it would not need to book provisions against those loan losses, subject to an implicit guarantee from the Punjab government that they would cover any additional losses.

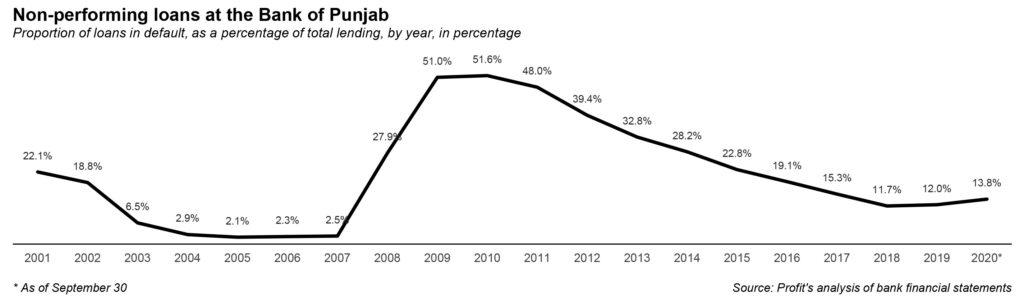

All told, that means that nearly Rs65.8 billion of the Rs134 billion in pre-crisis loans that the Bank of Punjab gave out went bad. Yes, that means that 49% – nearly half – of all loans given out by the bank prior to 2008 went into default. That is a staggeringly bad management of a bank.

Naeemuddin Khan, had his work cut out for him, but he was perhaps one of the best people who could have been brought on for the job. He had started his career as a banker in 1978 at Grindlays Bank. In 1991, he moved to Emirates International Bank. But it was his experience post-1998 that made him an interesting candidate for the job.

It was that year that he joined United Bank – then still state-owned – as part of the team whose job it was to turn around the bank in preparation for privatisation, a job that was successfully completed when the government sold its majority stake in 2002 to a consortium of the Abu Dhabi Group and the UK-based Bestway Group.

By then, Naeemuddin Khan had already moved on to the Corporate & Industrial Restructuring Corporation (CIRC), where his responsibility was to ensure the offloading of the rest of the government’s banking assets as profitably as possible, in large part by helping recover loans from defaulters, a job at which he excelled. Between 2001 and 2007, he helped state-owned banks recover Rs142 billion from defaulters of loans from the six state-owned banks.

So, when he was appointed for the job at the Bank of Punjab in 2008, he was clearly well-equipped to handle it. He worked towards strengthening the balance sheet of the bank, tightening lending standards and aggressively provisioning against bad loans to ensure that he kept chipping away at the Rs33.1 billion in bad loans against which they still did not have provisioning. It helped that for the next 10 years, he was working under Punjab Chief Minister Shehbaz Sharif, who – in the words of one Karachi-based banker – “thought of the bank as his baby”, which meant that the bank was kept largely free of political influence.

By the end of 2017, that Rs33.1 billion had been knocked down to just Rs14 billion, which Naeemuddin Khan decided to absorb in one year to get rid of it altogether and stop having to have an asterisk next to the bank’s asset numbers. The Bank of Punjab swung from a net profit of Rs4.9 billion in 2016 to a net loss of Rs3.3 billion in 2017, but the bandage had been pulled: the bank now had a clean balance sheet.

In December 2018, Naeemuddin Khan announced his resignation, leaving the post of Bank of Punjab president vacant for the next 16 months, until Zafar Masud was appointed to the job in April 2020.

Enter Zafar Masud

If Naeemuddin Khan was the surgeon skilled at fixing broken banks, Zafar Masud, aged 50, is the experienced builder who knows how to grow a banking franchise and has done it across two continents. And unlike most banking executives, Masud also has experience in running a government department, having served as the director general of National Savings in the Finance Ministry from 2016 through 2018.

Masud’s family background would have made it difficult to predict he would ever become a banker. His father is the famed television and film actor Munawar Saeed, his maternal grandfather was Syed Muhammad Taqi, one of the earliest editors of Jang, and his great uncles include poets Raees Amrohvi and Jaun Elia, and Indian filmmaker Kamal Amrohi. Boring old banking is not the family trade.

A 1993 graduate of the MBA program at the Institute of Business Administration (IBA) in Karachi, he started his career at American Express Bank in 1994, where he worked for a year before joining Citibank in 1995. For the next decade, Masud was either part of, or led, teams that helped bring new financial products to Pakistan’s corporate and investment banking sector, including the first ever US dollar-denominated Islamic bond issued by the government of Pakistan.

In 2005, he joined Dubai Islamic Bank to help set up their operations in Pakistan and led the corporate banking division immediately thereafter, a position he held for the next two and a half years. In 2008, he became head of Barclays’ southern Africa division, overseeing the British bank’s operations in Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Botswana, an operation that involved managing $3 billion in assets and a team of over 10,000 employees. He held that position before returning to Pakistan in 2011.

That year, he ventured into entrepreneurship, setting up Burj Capital, an investment bank with its own private equity arm. “Being an entrepreneur myself changed my perspective completely,” he said in an interview with Profit. “I went from having a secure salary of my own to being responsible for other people’s salaries.”

Masud helped run Burj Capital until 2015, when it was sold off to a private equity firm. Following that successful exit, Masud was appointed the director general of National Savings in 2016, a position he held for the next two years, during which he sought to modernise an archaic government department by investing in its technological infrastructure.

And in April 2020, right as the coronavirus pandemic was picking up steam all over Pakistan, Masud was appointed the president of the Bank of Punjab. One of his first actions was to announce that the bank would recognise its branch staff as frontline workers, and would grant them bonuses equaling one month’s salary. It was an action that would endear him to the staff.

Just one month later, he got on the PIA flight in Lahore heading home to Karachi to celebrate Eid with his family when the plane crashed. Miraculously, and in a manner that is still not entirely clear to him or anyone else, he survived.

The game plan for growth

A workaholic by nature, Masud – although grateful for his survival – was anxious to get back to the job he was hired to do at the bank, particularly since a big part of his pitch to the bank’s board during his job interviews had been to lead the bank into becoming one of the Big Five banks in the country. That represented ambition on a scale that demanded not just his attention to the job, but his full presence at the bank’s headquarters in Lahore. Recuperating at his family home in Karachi, while likely helpful to his recovery process, meant pressing pause on his ambitious growth plans for the Bank of Punjab.

Masud appears very cognisant of the fact that the bank is on solid financial footing, which provides him with the leeway to think aggressively about growth. “We inherited a solid platform with a strong balance sheet, with a CAR [capital adequacy ratio] above 17%,” he said. “We’re over 90% covered through provisioning against our infected portfolio [of bad loans] and the balance is secured against collateral on forced sale value. For the first time in 2020, we have done subjective classification and created the room for future shocks against marginal names in our portfolio as possible aftermath of Covid-19 impact on 2021-22 [earnings].”

That extra provisioning is likely to be helpful not just against the impact of the pandemic, but also against what are likely to be some growing pains involved in Masud’s aggressive growth strategy.

“There is big opportunity for growth on the lending side,” he said. “Currently, SME [small and medium enterprise] lending is 7.5% of our total private sector lending, agriculture 4%, and housing 1%. We would like to be the number one bank in all of these sectors with a portfolio size of more than 15%, 10%, and 5% respectively over the next three years.”

To grow the three segments of lending considered the riskiest in Pakistan from 12.5% of its total loan book to 30% of its loan book would require an aggressive growth strategy for finding new borrowers. In a state-owned bank, particularly one with the kind of history the Bank of Punjab has, that might lead to concerns about a repeat of what happened in 2008. Masud appears to anticipate that, and offers his plan.

“While we’re planning to go aggressively on the lending side, we would like to be more prudent in ensuring robust compliance, risk and audit environment,” he said. Among the actions he plans to take: centralising operations and reporting away from the branches and in headquarters, which will ensure stricter compliance with the bank’s lending policies. The bank is also hiring personnel from other banks who have a strong track record in operations and compliance, and is revamping its risk-scoring and lending methodology.

He also lays out other goals for growing the bank’s revenue, which includes growing its fee-based income. “We have very small contribution of fee income. We would be focusing on trade, cash management and investment banking businesses and will be leading the transactions in these areas going forth.”

And he wants to grow the Bank of Punjab’s non-banking financial services portfolio as well. “We’re looking at the possibilities of launching an insurance company jointly the government of Punjab,” he said. “Our existing modaraba and brokerage businesses are being restructured as we see that as a huge opportunity to do out-of-the-box businesses, particularly in the space of low-cost housing.”

While all of those are targets that will help the bank achieve greater profitability, unto themselves, they are not enough to help achieve the major goal Masud highlighted for the bank: cracking the ranks of the Big Five. For that, there is one metric that matters above all else – deposits – and it is a harder challenge than it looks.

Can Bank of Punjab crack into the Big Five?

Of all the goals Masud laid out, this one is the most ambitious: becoming a Big Five bank in the next five years. Before we assess how realistic this goal is, let us first set out some definitions: when we measure a bank’s size, we could do so by total assets, total revenue, total market capitalisation, or total deposits. In the Pakistani context, we almost always rank banks by total deposits.

At one level, the target looks achievable. The fifth largest bank in Pakistan is Allied Bank Ltd, which – at the end of December 2019 had Rs1,049 billion in deposits, about 52% larger than Bank of Punjab’s Rs691 billion. To outgrow ABL, the Bank of Punjab would need to grow its deposits by 8.7% per year faster than ABL. How hard is that? Over the past five years (2014 through 2019), the Bank of Punjab grew 5.1% faster than ABL, meaning increasing the bank’s deposit growth rate by about 360 basis points – not easy, but well within the realm of doable – would achieve the goal of becoming bigger than ABL.

That assumes, however, that ABL will remain the fifth-largest bank in Pakistan, which is unlikely to remain the case over the course of the next five years. As we have previously report, both Meezan Bank and Bank AL Habib are likely to grow larger than ABL by early next year at the latest, so if the Bank of Punjab is to crack the Big Five, it will have to ensure that it can beat not just ABL, but also Meezan Bank and Bank AL Habib. And given the fact that Meezan is both larger and faster-growing, really, the bank that BOP needs to beat is Meezan Bank.

That is where the challenge gets much harder. Meezan is one of the fastest growing banks in Pakistan and has been for the past two decades. It is the juggernaut that has barely shown any signs of slowing down since it first started operations in 2002, never once having had a net loss in its entire history.

Between 2014 and 2019, Meezan Bank has been growing its deposits at an average of 19.6% per year, compared to the Bank of Punjab’s average of 15.1% per year. In order to surpass Meezan Bank, the Bank of Punjab would need to increase the average growth rates of its deposits by of 618 basis points (one basis point is one-hundredth of one percent) above Meezan Bank’s growth rate.

Assuming Meezan Bank’s growth rate over the past five years is comparable to its growth rate over the next five years, that implies than the Bank of Punjab needs to grow its deposits by an average of 27% per year over the next five years. Is that doable? Yes, but it will be very difficult. Over the past five years, only one bank in Pakistan has growth faster than that: JS Bank.

Masud appears quite aware of just how tough this challenge is likely to be. “The elephant in the room is our customer deposit profile,” he said. “We have aggressively grown our deposit base over the last ten years, but the profile of our deposit in terms of segment-wise mix and cost needs significant improvement. Over 60% constitutes public sector deposits.”

“We plan to leverage our branch network, which is currently underutilised, to ensure that we not only continue growing the deposit base, and simultaneously improve the deposit mix,” he said. “I believe, this will be very challenging, but am confident that with a focused strategy of leveraging our network and resources, improved products supported by technology and digital initiatives, we will be able to accomplish this goal.”

To accomplish this ambitious target, Masud lays out three key levers: geographic expansion (mainly in Sindh and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa), improving the bank’s digital infrastructure to help attract retail deposits from technology-savvy urban customers, and an expansion of its Islamic banking division which may include setting up a separate Islamic banking subsidiary, similar to the one MCB Bank set up in 2015.

The strategy of increasing branches and improving technology are – at this point – table stakes for being a major national bank. Setting up a separate Islamic banking subsidiary, however, may have significant potential. When MCB Bank did so, its Islamic banking deposit growth rate jumped to 71.6% per year in the first four years after it created MCB Islamic Bank in 2015. In the four years preceding that, MCB’s Islamic banking deposits grew by an average of just 6.6% per year.

Obviously, given the fact that MCB Bank’s Islamic banking division was much smaller in 2015 (Rs9.5 billion in deposits) than the Bank of Punjab’s is today (Rs54.6 billion as of September 30, 2020), achieving a similar increase in growth is unlikely. Still, a significant boost to Islamic banking deposit growth – a very realistic target – could be the key towards getting the bank towards its goal of becoming one of the Big Five banks.

The challenge, of course, is the fact that the bank they need to beat is the one that is synonymous with Islamic banking in Pakistan. Any other brand will face an uphill battle in convincing depositors to switch over to its Islamic banking business.

In other words, the odds of success – while not zero – are not easy for the Bank of Punjab. But then again, Zafar Masud is the Miracle Man who survived even worse odds. Less superstitiously, he has built and grown financial businesses for the bulk of his career. Can he pull off a miracle for the Bank of Punjab here? Maybe.

More importantly than whether or not he can achieve this goal, however, is one of the reasons behind the goal that he articulated. “We want to grow our business in provinces other than Punjab and help businesses and people, and in the process maybe help alleviate the impression that people in smaller provinces have that Punjab hoards resources. If we are able to do so, maybe we can help improve interprovincial harmony in the country.”

Now, that is a miracle worth praying for.

(Disclosure: Zafar Masud is the brother-in-law of the author of this story.)

Analytically sound – valuable informative article – should be highly useful in realistically- robust aspired planning for the future !!… in doing so – some out of the box, aiming to produce optimally lot more from less – inshaAllah,

Haider Zaidi, BIPP Consortium Associate

I love Zafar Sahib. One of the great man and I want to do a request to him where he have great personality and giving the boat the Punjab bank. I need his a kind favor. In my life he is my ideal man and a great leader.