Most clothes in Pakistan are tailor-made. It is a strange phenomena of the third-world that a majority of people that would be considered not well off wear bespoke clothing. The major reason for this is cheap labour. Skilled tailors are everywhere and they do not ask for the kind of money that their skilled work deserves and should fetch in more developed countries.

This means that it is cheaper to buy loose cloth and ask your local tailor to stitch it according to your measurements. Buying off the rack from brands is actually a status symbol since those clothes are more expensive. In most western countries, high-end brands particularly for things like suits often have in-house tailors, or high-end tailors often sell fabric as well.

But one of the fabrics that have historically not been able to be bespoke is denim. Hard to work with and increasingly in demand, denim products like jackets and jeans need special craftsmen. The journey of denim began in 1873, when Levi Strauss and Jacob Davis obtained a U.S. patent on the process of putting rivets in men’s work pants for the very first time. Tough yet comfortable to move around in, denim was first used for clothes worn by workers because of its high durability. Then it became widely popular in the 1930s when Hollywood started making cowboy movies in which actors wore jeans.And from that point onwards denim clothing spread along with globalization.

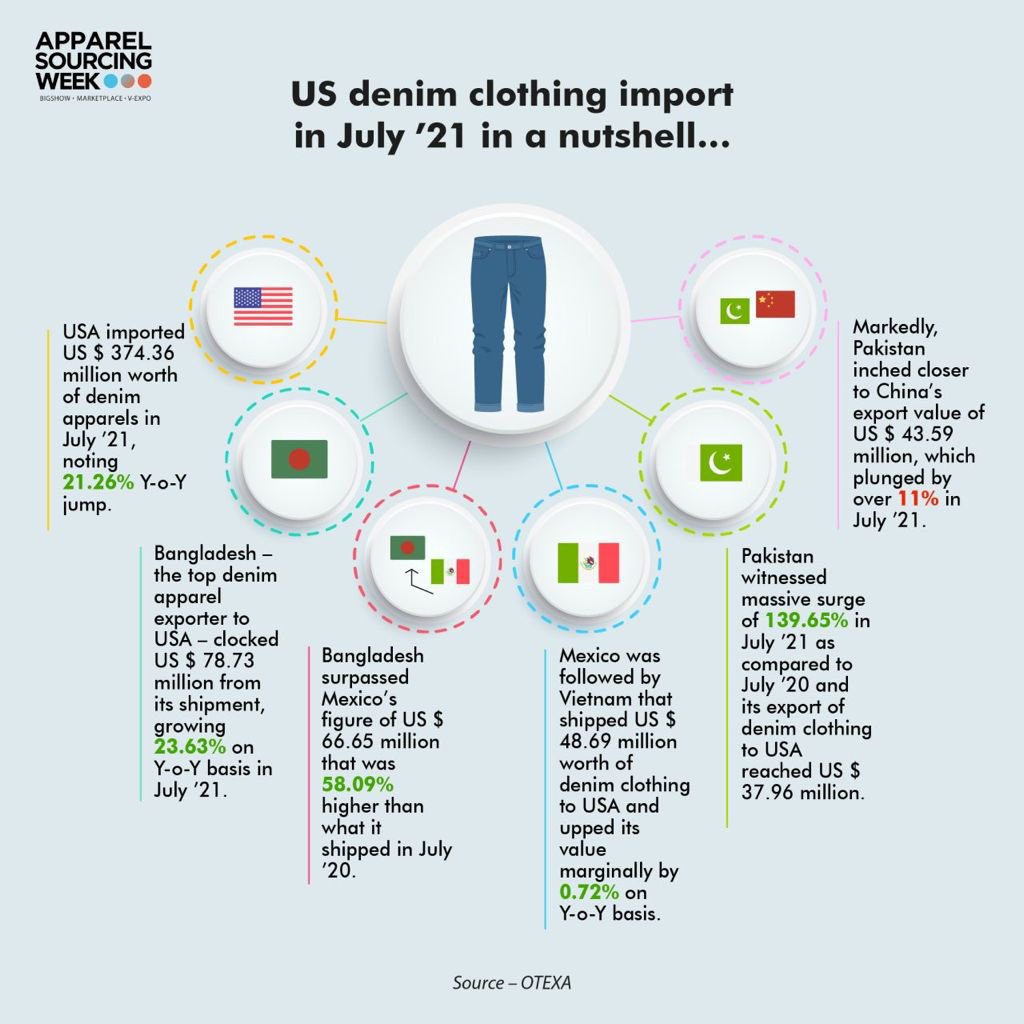

Denim also happens to be one of the fabrics that Pakistan is good at producing. The manufacturing of denim garments is a complex, difficult and lengthy task that is performed step by step. It is an art that has been perfected by hundreds of small and large factories in Pakistan, which produce world-class denim garments. That is why Pakistani denim is popular everywhere, including in European countries. In fact, in July 2021, Pakistan exported denim clothing worth $38 million to the United States and these figures were released by none other than the US Office of Textiles and Apparel. And while Pakistan has managed to increase its denim exports by such huge numbers, there is still some doubt as to whether this level of exports can be maintained.

Rising exports

One of the main things you hear from almost every sector is the need to increase exports and decrease imports to improve the balance of payments. Producers like to export products because they get a better price and it is also in the government’s interest, so the success of denim this last year is a win. Interestingly, the volume of exports was 140 percent higher than in July 2020 last year. This was also part of a larger trend in the region and beyond.

According to the data, denim exports from Mexico increased by 58 percent during the same period, while exports by Bangladesh increased by 24 percent. The data also shows that among Asian countries that supply textiles and garments to the US, Pakistan’s exports to the US have increased by 62.16 percent to $188.94 million. Similarly, Bangladesh’s exports increased by 42.82 per cent to $362.38 million during the period, while imports from China increased by 13.28 per cent to $192.49 million.

Bilal Chaudhry, who deals in local and imported readymade garments in Karachi, Faisalabad and Lahore, believes that this time Pakistan’s denim has dominated not only international but also local markets – which are often not hotspots for world-class denim since these products are very expensive. However, with the increasing exports this year, there has also been a massive increase in export leftovers which people are now buying.

Bilal claims that earlier the clothes available on the market were of a subpar quality. All of the good denim products would be exported and we would be left with lower quality items. “You could not find good clothes here because many shopkeepers display clothes that are not fit to be worn. If the fabric is of good quality then the sewing will be inferior and if the sewing is good then the quality of the fabric will be very poor,” he explains. “Since earlier exports of readymade garments from Pakistan were not high, export leftovers were rarely seen in the market and even if one had them available, the defects of this garment were clearly visible.”

This is where the pandemic might have actually helped local denim producers. Until the lockdowns were first imposed, the denim market was dominated by brands like Levis. When the Covid lockdown was imposed business was severely affected, but online sales remained high. At this point, sellers started importing denim from China, Bangladesh, and Turkey. They were imported at reasonable prices and sold hand in hand.

This is where there was a twist in fate. Around the time that Pakistan began recovering from Covid and lockdowns were being lifted, countries like Bangladesh and Turkey, from whom we had been importing before, went into lockdowns of their own and started looking towards Pakistan for denim. It was also at this point that the US demand started to look towards Pakistan for denim. “Pakistan filled the gap for a while and that is why our exports rose. All of these orders were completed by Pakistan and our exports rose,” says Bilal. “At the same time there was also a huge amount of export leftovers which then appeared in the local market and began giving the big brands a serious run for their money.”

It was a simple process. Suddenly there were a lot of high-quality denim products available on the market for cheap. Earlier, small retailers would buy low-quality products from factories and would not cater to the same segment that would be buying clothes from places like Levis. However with export leftovers, suddenly these small retailers were selling the same quality of products for cheaper. Since these small retailers often operate in the same markets as large brands, they began undercutting the sales of these brands on the local market as well.

“Take the example of a single pair of jeans. Earlier, the best quality pair of jeans from a local factory would be available for Rs 400 to Rs 700 to the retailer. However, even the best quality available to us was not what is considered ‘export quality.’ We were not playing in the same league as the large brand names. Now there are plenty of factories that have thousands of denim export leftovers and their quality is high and can compete with places like Levis. Everything in the country is becoming more expensive but denim products have actually risen in quality and fallen in terms of price.”

Earlier, when the non-export quality pants were available for Rs 400 to Rs 700 from factories, retailers are now buying export-leftovers for Rs 250 to Rs 500 from the factories and selling them between Rs 800 to Rs 1200, which leaves both customers and retailers very happy. In fact, the denim products that these retailers imported back when Pakistan was under lockdown is sitting in warehouses collecting dust since it is of the same quality but significantly more expensive.

“Since the cost of a pair of jeans that we import costs us about Rs 900, selling it at Rs 1,200 is not a very lucrative deal. Similarly, denim jackets were easily available in our local markets. Some of the big brands had these jackets available and their price was not affordable to everyone. Right now, denim jackets in the market are only between Rs 1500 to 2500. People used to buy used denim jackets from Landa Bazaar and were happy to wear used jackets but now the new ones are easily available in the local market at cheaper prices. Similarly, the markets are full of denim shorts and they are selling for only between Rs 300 to Rs 500. And all of these export leftovers are branded products from brands like Levis, Zara man, Lee, Gucci, True Religion, Polo and Diesel. Now ask yourself how the rush in the markets will not increase,” says Bilal.

Is this sustainable?

Right now the government has set a target of doubling textile exports by 2025 and has announced a new policy with billions of rupees in subsidies. It has not been officially announced since it is still pending in cabinet for approval. The problem is that the government does this with everything. It sets ambitious targets and sets itself up to fail because those targets can either not be met or are the wrong way to go. Take the example of cotton, where . The government keeps setting ambitious ‘targets’ but never meets them because it does nearly nothing to actually help farmers achieve those Soviet-style macroeconomic goals.

Currently, there is not really an issue of Pakistan’s cotton production or exports falling, the problem is of failing to meet targets. The example is also pertinent because denim is made using almost all-cotton. The recently approved long term textile policy 2020-25 has laid down a clear vision for how much Pakistan hopes to be exporting by the end of this decade. Under the plan, textile exports should be up to $25.3 billion by the end of 2025, and depending on the success of these five years, at $50 billion by the end of 2030.

For this, the country needs to increase not just the amount of cotton it produces, but also the quality of the cotton crop. Currently, Pakistani cotton is considered second grade, and if the crop quality is improved there would be greater demand at a greater price which would be a big boost towards meeting export targets. More importantly, by improving the crop, the entire textile industry will benefit since the quality of all products will improve at the source. Pakistan has been missing its export targets since last year. In 2019, the production target for cotton had been 15 million cotton bales, and only 10.2 million bales were produced.

The reason behind this, again, is that the government places very little emphasis on how the cotton is grown. Factors like climate change, lack of proper research by local research institutes, and no cotton policy, and the loss of cotton production areas to other cash crops have all played a role in this, which is why it is so important to focus on techniques to grow more and better quality cotton. Similarly, if Pakistan is to keep up the increased denim exports and production it must focus on how it is producing and to what end.

The new policy is ambitious, and aside from the silly targets it sets, under this policy, electricity and gas tariffs will be reduced. In addition to long-term financing for the textile industry and increasing access to new markets, it is also proposed to increase the efficiency of human resource development.

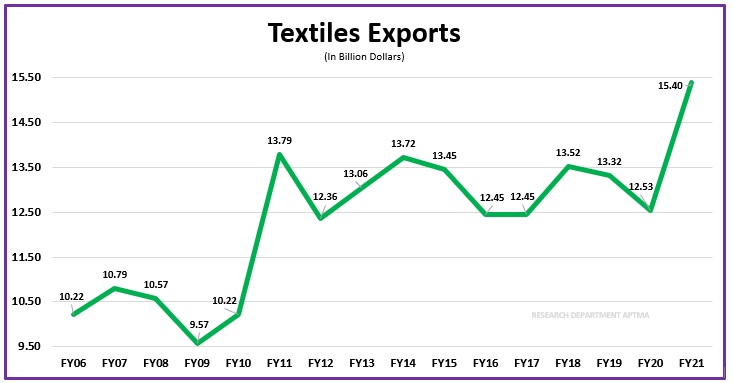

However, Abdul Rahim Nasir, chairman of the All Pakistan Textile Mills Association (APTMA), believes that the new textile policy will create 100 new textile industries in Pakistan, adding 20 billion annually to the sector’s exports and it will also increase exports as well as create hundreds of new jobs. According to the chairman, exports of the textile sector increased by 23 per cent during the last financial year and the volume of exports increased to $15.4 billion from $12 billion. Similarly, the total exports of the textile sector during July and August 2021 was recorded at $2.93 billion as against $2.28 billion in July-August 2020.

Despite the Covid-19 pandemic during the last fiscal year 2020-21, Pakistan’s textile sector showed significant growth and the volume of textile exports increased to $15.4 billion. Earlier, in December 2020, the federal government had set a target of $20.86 billion for textile and apparel exports over the next five years. The federal Ministry of Commerce had set a textile export target of $13.6 billion for fiscal year 2020-21, but the total volume of textile and apparel exports increased to &15.4 billion at the end of the year.

Mian Noman Kabir, President, Lahore Chambers of Commerce and Industry (LCCI), informed Profit that the number of export oriented companies is undoubtedly increasing and Pakistan’s textile sector is also increasing its exports significantly. “Companies that export anything from Pakistan need a Certificate of Origin and if you look at the statistics of the last few months, they are increasing exponentially. The potential of the textile sector is not hidden from anyone and in my view our textile exports will be sustainable,” he said.

The thing to think about here is that last year the Covid-19 caused problems to all sectors around the world, but it proved to be beneficial for Pakistan’s declining textile industry. Due to the severe lockdown in India and Bangladesh compared to Pakistan, their export sector, especially the textile sector, was badly affected, which the global markets had started placing orders to Pakistani traders to fill the gap and according to the latest data, Pakistan’s textile exports, especially denim fabrics, have also increased significantly.

But the question is, how sustainable is this export situation? A look at the data obtained by the All Pakistan Textile Mills Association (APTMA) reveals that textile exports in 2020 were $11.67 billion that was $770 million less than 2019.

These figures contradict all government claims that the textile industry has fully recovered and that it is becoming increasingly difficult for Pakistan to meet global orders. Because these figures prove that textile exports are gradually declining. Yes, the textile sector was less affected by the lockdown during Covid-19 pandemic than other sectors, which cannot be attributed to improvement. In addition, no official figures have been released to gauge what percentage of the industry is operating. What does it mean to work at full capacity? If there has been a 50 per cent increase in the working of industries, then there should have been a 50 per cent increase in exports, which is not visible and this fact is also admitted by a number of APTMA members.

Pakistan’s neighbor India exports $36 billion worth of textiles annually, three times more than Pakistan. If we compare Pakistan with Bangladesh in terms of area, population, resources and economy, its textile exports are more than $34 billion. Due to the energy crisis and the poor peace situation in the last fifteen years, Pakistan’s textile industries have rapidly migrated to Bangladesh and India. The secret behind the growth of textiles in Bangladesh and India is that electricity rates for industries there are half that of Pakistan. Uninterrupted and free water is provided and affordable labor is also available. Due to Bangladesh being underdeveloped, tariffs are also discounted in international markets. In this way, Bangladesh and India produce goods at 20 percent less cost than Pakistan, which is also available in international markets at cheaper prices than Pakistan. That is why buyers prefer Bangladeshi and Indian products instead of expensive Pakistani goods.

Many industrialists in the textile sector believe that there is a lack of branding and innovation in textiles as in every other sector in Pakistan. Since most of the textile industry’s goods are consumed in the local markets, no attention is paid to producing world-class goods. Compared to Bangladesh and India, we have only a few multinational brands of textiles and garments that is why we have almost no foreign investment in the export sector.

According to statistics, the textile sector accounts for 46 per cent of Pakistan’s manufacturing services, employing 1.5 million people. The development of this sector is directly linked to the production of cotton. Until a few years ago, Pakistan was ranked fourth with 1.5 million bales a year but now the production is limited to 700,000 bales. The situation of cotton has deteriorated to such an extent that the cotton exporting country is now forced to import on which additional capital is spent. Factors leading to a decline in cotton production include climate change, agricultural interventions such as the high cost of seeds, sprays, fertilizers and water, as well as the government’s inattention.

Cotton production per acre in Pakistan is much lower than other countries in the world due to lack of research and development. Farmers do not have access to cotton seeds that can produce good yields while resisting climate change and diseases. Research by agricultural research institutes and universities is limited to paperwork only and that is why most varieties fail in the field at a temperature of 38 degrees Celsius. Cotton is not part of the agricultural emergency program, nor is there a minimum support price for this important crop. In contrast, subsidies and minimum support prices are announced for the sugarcane crop, which is why cotton growers are increasingly moving towards sugarcane.

If we really want the sustainable export of the textile sector, we have to take revolutionary steps to revive the cotton industry as well as the textile industry. In this regard, APTMA Secretary General Punjab Raza Baqir informed Profit that although it is not the job of APTMA to improve the production of cotton or its condition, a cotton foundation has been established by APTMA.

“Cotton experts have been appointed for this foundation and we are also in talks with the Punjab government to lease us lands where seed development work can be done. In fact, the exports of Pakistan’s textile industry have flourished because of the Covid-19 Pandemic because in Pakistan, there was a smart lockdown and our sector continued to operate but the most important thing is that the new clients that our exporters have now should be given good services and rates so that our exports can be sustainable in the future.”

“The role of the government is very important because 40 per cent of the cost of production comes from energy which is not variable. The other problem is freight at the moment because the sudden increase in demand after the Covid-19 lockdown has created a severe shortage of containers all over the world and where they are available, their price has increased five times. This is an issue that affects both exports and imports, but this situation is temporary and will hopefully improve in two to three months,” he concluded.