When does it make sense to leave Pakistan, and when does it make sense to come back home? Embedded in the consciousness of Pakistani society are seemingly fixed and undisputable answers. When does it make sense to leave Pakistan? At the very first feasible opportunity. When does it make sense to come back home? Never, if possible.

Given the state of Pakistan’s political economy over the last two years, those answers seem to have further been ingrained in people’s minds. Leave, and never come back home, many, many people seem to be saying not just with their words, but with their feet, given the rise in emigration numbers.

Emigration from one’s homeland is a deeply personal decision and one that can have multiple dimensions to it, not all of which will be common across people. But it does have an economic one as well, and one that lends itself well to examination through the lens of personal finance.

As people in living rooms across Pakistan talk about trying to leave the country, we cannot claim to offer a guide to everything relating to that decision, but we do believe that we can offer the economic layer, or at least some important tools in understanding the economic layer, of that decision.

In this article, we will lay out three components to the decision: what kind of income a prospective emigrant should be willing to accept in order to be financially better off in the country they are moving to, how immigration laws in their destination country should affect their decision, and what kind of factors would mean that it makes sense to come back home to Pakistan?

We will also state an opinion up front: the top of the emigration opportunity spectrum (those with the most means and most opportunities in both Pakistan and abroad) are most better off leaving, as well as those at the bottom of that spectrum. The picture is more mixed for those in the middle, and hence they should probably do a bit more homework before deciding to leave.

But first, some numbers on where people are going.

The data on emigration

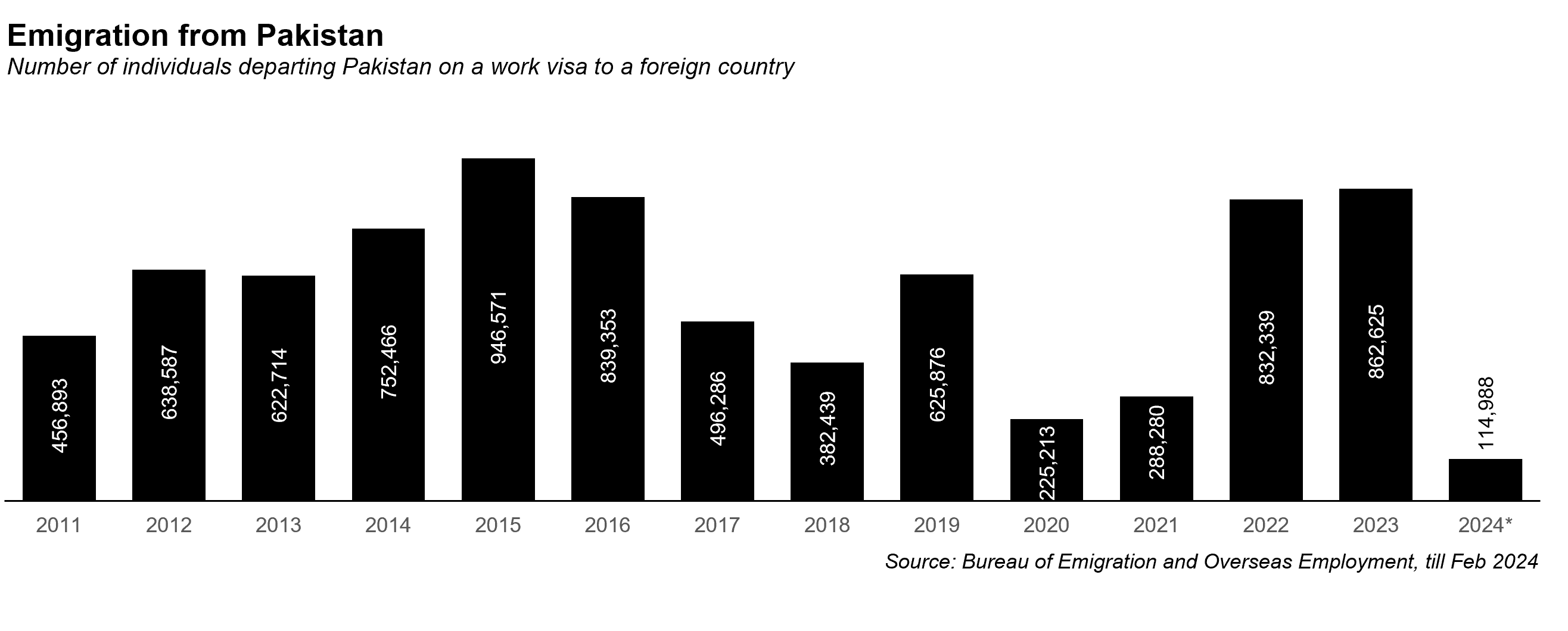

Say what they will about patriotism, Pakistanis do love to move out of the country. According to the admittedly incomplete data from the Bureau of Emigration and Overseas Employment, 862,000 Pakistanis left the country for work in 2023, the highest since 2015, when 947,000 people left the country.

(Note: the 2015 number might be artificially higher for two reasons: the government started getting better about keeping records of emigration that year, and Saudi Arabia had a massive increase in the need for labour that year as well, owing to the launch of several infrastructure projects, shortly after Mohammed Bin Salman became the de facto ruler of that country in January 2015.)

Data on emigration is not well-kept, not least because the government does not keep track of people whose first exit is not on a work visa, and does not keep track of people who have come back, nor of people who come back and leave again.

As a result, in government statistics, it looks like very few people have left Pakistan for places like Canada, the United States, and Australia, even though if you look at statistics produced by those governments, you can see that there are at least a few thousand Pakistanis moving there every year (sub-15,000 per year for each of those three countries, and closer to 10,000 per year for each of them.)

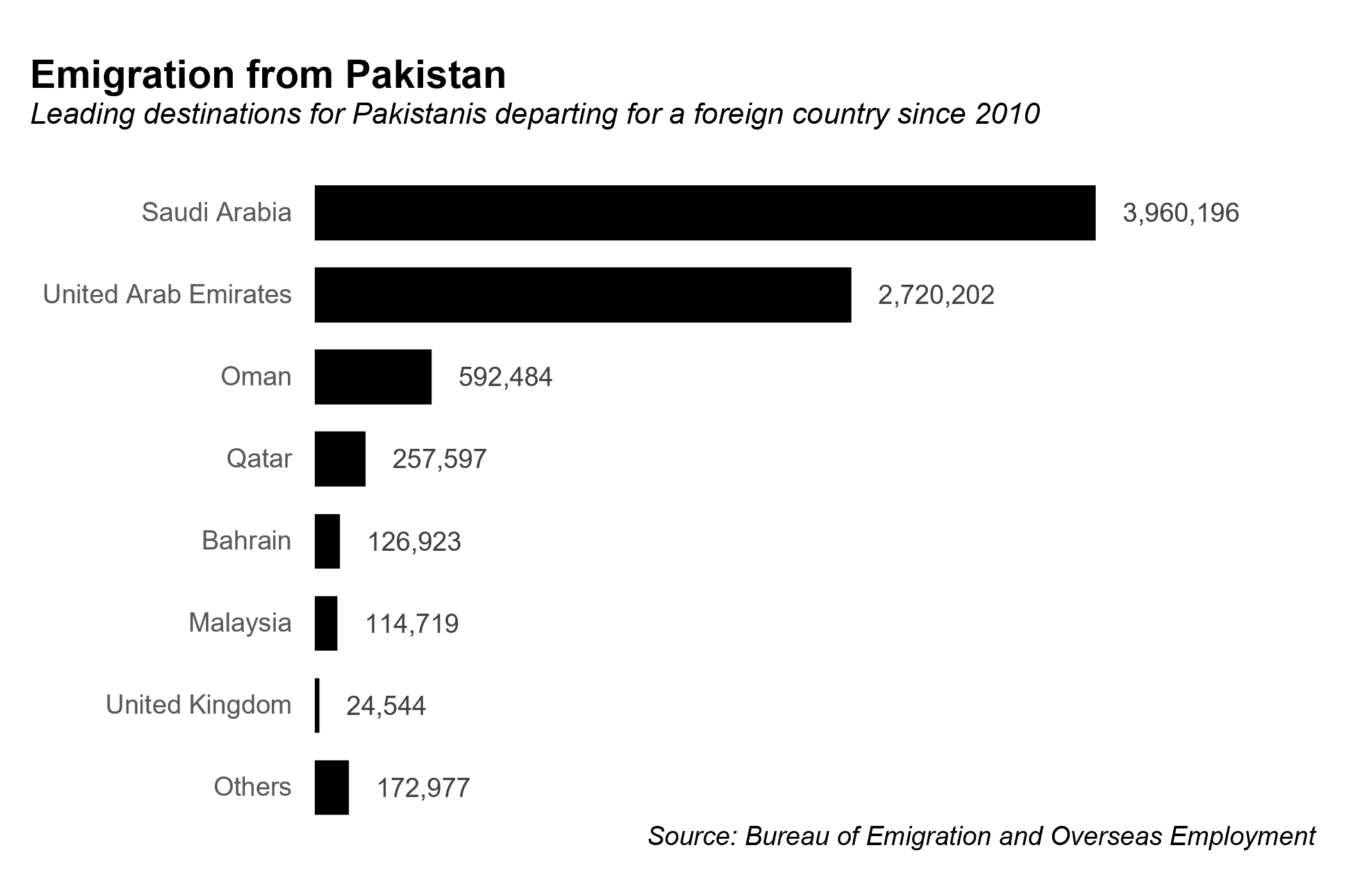

Nonetheless, even allowing for those short-comings, it is abundantly clear that when Pakistanis talk about moving out of the country, they are largely talking about moving to the Gulf Arab states, and really very specifically to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Five out of every six Pakistanis who left the country for work since 2010, according to BEOE data (84% to be precise), go to those two countries.

That proportion does not correct for the undercounting of emigration to the US, Canada, and Australia. But even adding about 30,000 a year to those countries’ count would not materially reduce the dominance of Saudi Arabia and the UAE as destinations for Pakistani workers.

We tried to do a wholistic accounting of emigration to those countries, but the only one that gave out detailed data is the United States, and the BEOE data on the United States, while undercounting the number of Pakistanis who move to the US work, nonetheless is not off by more than 1,000-2,000 per year. It is also difficult to do comparable numbers across those countries. While in Canada and Australia, the majority of Pakistani emigres arrive as legal permanent residents, in the United States, more than half of Pakistanis first arrive as students or employees before eventually converting to a green card.

What makes moving out worth it?

So, what makes a move worth it from a strictly financial perspective? Simply put, your standard of living – specifically the purchasing power of your income – should be higher in the place that you move relative to the place that you came from.

That phrase “purchasing power” is key. It is simply not enough to make more in absolute terms (you almost certainly will make more when you calculate the value of your foreign income in rupees), but one must make more by a large enough margin to sufficiently cover the higher cost of living in one’s destination country. This might seem obvious, but calculating what that means is not exactly easy.

Specifically, there are two complicating factors: the first is that data on cost of living comparisons is not something that is often readily available (but will be made available through this article). And the second factor is that a large majority of Pakistanis are living in family homes and not homes that they pay rent or a mortgage on, and hence often do not factor in the implied cost of replacing that home to which they have free access, when deciding to move.

(The implications of this second factor are interesting: Pakistani employers are being subsidised in their cost of labour by our joint family system.)

What we have done is tried to do that calculation for you: showing how much a prospective emigrant from Karachi, Lahore, or Islamabad might need to make in a number of foreign cities and metropolitan areas in order to be financially as well off as they are in Pakistan.

For cost of living data, we utilised the estimates compiled by The Economist Intelligence Unit for all foreign cities and for Karachi, and then calculated the implied values of the cost of living index for Islamabad and Lahore using comparative real estate prices from Zameen.com’s index for home prices.

See Profit’s Cost of living index calculations

(Note: Yes, the Economist data is from the perspective of western expats living in cities around the world, but we would argue that prospective emigrants are seeking a lifestyle more similar to those expats than to their own countrymen, and hence the use of that sort of data – and the relative index levels – are still useful in calculating those differentials in the cost of living.)

From there the calculation is straightforward. Convert your salary into the relevant foreign currency, multiply it by the cost of living index value of the city you wish to move to, and divide it by the value of the cost of living index for your home city. The resultant number should serve as a baseline of the kind of income you should be targeting – or hoping to exceed – if you are considering moving to another country. If you live in a family home, you should add the approximate rental value of a home similar to the one you live in – or home you would be willing to accept living in – before doing the currency conversion and index calculations.

How would you find out the number for the foreign salary you should be comparing against? It helps to know people in your own industry who have moved to the country you are considering moving to. For those who do not have such connections, perhaps looking at salary data for companies in your industry on websites such as Glassdoor might help.

Whatever source you use, do not go into this blind. Arm yourself with data on what the market rates are for salaries of people at your level, and assume you will have to take a demotion – either in seniority level or even in function – because that is simply what is called the “immigrant tax”: the reason people from other countries let you in in the first place is because they get your talent for a price cheaper than what local talent would be getting.

In other words, expect to make less than a local, but if you have some information about how your desired foreign market works, maybe you will be able to avoid completely being taken advantage of. With that salary data in hand as a baseline, you can then start thinking about what immigration will mean for you.

When we say baseline, we really do mean that sincerely, since this is where the limits of personal finance end and other factors begin to take hold.

For instance: are you reluctantly moving away from family, or are you eagerly running away from them? If the former, you should hope to make at least your baseline or higher to compensate for the distance from family. If the latter, maybe you’d be willing to take even less than the baseline number just to get away.

(For those of you in your 20s who want to escape your families because you are in the middle of The Big Fight about marriage, just remember that emigration does not actually solve The Big Fight. It merely puts it on ice, and the Fight will resume every time you visit. Better to get it over with and resolve it rather than looking to emigration as the solution.)

With all that said, let us take a look at some of the results. For someone who makes about Rs200,000 per month in Karachi, and lives in a family home that would take approximately Rs150,000 per month in rent to replicate, they should make at least a little over AED 10,000 per month if they wish to move to Dubai to live a comparable life. For someone who makes Rs500,000 per month and lives in a nicer house – say the kind that would take Rs300,000 per month in rent to replicate, they should seek to make closer to AED 23,000 per month in Dubai, SAR 24,000 per month in Riyadh, and C$100,000 per year in Toronto.

Editor’s Note: Some readers might find a difference in the costs of living laid out above and what they might have gleaned in casual conversation from family and friends living in Dubai. This difference could be because of a difference in consumption habits of an average Pakistani family compared to a typical western family, and the relative weights that the Economist Intelligence Unit assigns to each category of goods and services. For example an average Pakistani family, due to its larger size, might have higher schooling requirements than a typical western expat. This would lead to a need to earn a few thousand additional Dirhams than the calculations shown above, as schooling, compared to other consumption categories, is substantially more expensive in Dubai as compared to Pakistan. Readers are advised to make certain adjustments based on their own circumstances.

For some of you, in certain professions or perhaps because of your personal credentials and circumstances, these numbers can be easily beaten, and if that is your situation, then we cannot argue that emigration would make you worse off from a purely personal finance perspective. What would be left for you at that point would be to consider the non-financial factors such as distance from family, the extent to which you feel comfortable living in Pakistan because of your personal circumstances (e.g. women who like going for walks are probably more comfortable in Canada than anywhere in Pakistan), or any other factors.

The more astute of you will notice that we do not seem to make any calculations regarding the relative taxation levels of the countries we are offering for comparison, which might seem like a grievous oversight, considering the zero income tax rates of the Gulf Arab states.

That is not an oversight. It is quite deliberate. The late US Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, said “taxes are the price we pay for a civilised society.” Western countries may charge far higher tax rates than the Gulf Arab states, but we argue that what looks free in terms of zero income tax comes at a high cost, and the high taxes of Western countries come with benefits that are worth paying for.

The citizenship question

The problem with migrating to the Gulf Arab states – despite their zero taxes and first world infrastructure – is the fact that they require you to accept the fact that no matter how much of your life you spend there, you will never be allowed to call those places home. That no matter how hard you have worked there, one lost job, one spate of bad luck, one car accident could mean that you have to leave the place you have built a life in, and come back to Pakistan without a plan.

We are now half a century removed from when Pakistanis first started moving to the Gulf en masse, and while there are many stories of success, there are also many stories of broken men returning home with little to show for their labour. Many who have raised their families in Saudi Arabia and UAE and have children who know no other home, but who must find ways to beg and plead with the governments in those countries to allow them to stay.

Contrast that with those who move to the US, UK, Canada, or Australia and find themselves able to secure citizenship which, once in hand, gives them equal right to call those places home, for their children to plan to spend their whole lives there without asking anyone for permission, for their education and retirement to be the taken care of by the social contract in those countries.

You would be entitled to the same pension as the native-born alongside whom you worked, your children could attend the same free public schools, attend the same free (or subsidised) universities, and you would have access to the same healthcare (free public, or employer insured) as anyone else in those societies. Where you were born would not affect any of it.

In other words, once you move to the West, you do not need an exit plan. If you move to Saudi Arabia, the UAE, or any other Gulf State, you absolutely need an exit plan. Some of the more well off emigrants to the Gulf Arab states save up to buy permanent residency in Western countries, which eventually allows their children to become citizens of those states.

But only fools move to the GCC without a plan for what to do next.

How to think about moving back to Pakistan

Fully recognizing that this sentiment will be mocked, but we would argue that moving back to Pakistan can make a lot of sense for many, if not most, emigrants, especially those who moved to the Gulf Arab states, but even those who have migrated to the West.

If you live abroad, try that same calculation from earlier in the article in reverse. As an example, we will use a certain professional who lives in New York and makes about $400,000 a year. To move back to Karachi, he could accept a 72% pay cut and come out at breakeven in terms of the purchasing power of what he would be able to get in Karachi.

Granted, a Rs2.6 million per month salary is not very common in Pakistan, but for this finance professional, a banking sector job that paid Rs1.7 million in monthly salary and paid out industry average bonuses would result in the same compensation level – in purchasing power terms – as what he is currently making in New York. That number – while still not very common – is perhaps a bit more realistic. Add in the pull factor of family, and perhaps even a lower number would do the trick.

A banker in New York making $400,000 a year and considering a move back to Karachi is relatively rare. More common might be someone who lives in Dubai and makes AED 50,000 a month. To move back, they would need an income of about Rs1.7 million a month, or – if in banking – a base salary of about Rs1.2 million a month. If they make AED 35,000 a month? Maybe even a Rs800,000 a month salary with a hefty annual bonus would result in a comparable purchasing power.

In other words, people make the mistake of not discounting correctly for how much less they need to make in Pakistan in order to afford the lifestyles they have grown accustomed to abroad. Yes, Pakistan has a lower quality of infrastructure, but it also has other comforts that those countries do not have, most commonly, proximity to family.

One assumption underlying the entirety of the conversation thus far about relative compensation and cost levels is that we have so far been talking about point-in-time comparisons. We have yet to look at the way salary levels vary across the span of one’s career, and how those rates of change differ across economies. This is necessarily complex and very difficult to do, since this kind of data tends to not be readily available for most economies.

Without the benefit of robust data to back up this piece of the analysis, it can be argued that the biggest pull for emigration from Pakistan often comes for white collar workers when they hit their early 30s. Salaries in Pakistan for white collar workers start low, but for the first 5-10 years of one’s career, they rise quite rapidly. It is not uncommon for people to be making 3-5 times their starting salary before they hit 30. Even accounting for high inflation in Pakistan, that represents a substantial increase in buying power.

Once you hit 30, however, the middle management curse kicks in. A handful of high-fliers continue to get promoted and see substantial income increases, but most people find themselves making about the same in inflation-adjusted terms for a decade or more. Sometimes, as in 2022 and 2023, when inflation rises very rapidly, those salaries do not rise fast enough, and one finds oneself in the position of making less in inflation-adjusted terms than in earlier parts of one’s career.

By contrast, incomes in the West, at least (and perhaps even in the Gulf) tend to keep rising until one hits about the age of 40 at which point they plateau at a higher level than in Pakistan – even in purchasing power terms. Why is this? Because those economies are larger, there are more large companies serving them, meaning more layers of middle management required, which means one can keep rising for longer while still being in the middle of the organisational pack. Companies in Pakistan are smaller, so it does not take as long to get close to the top and then be stuck for a long time.

What this means is that, if you are planning on leaving Pakistan, leave as close to your 30th birthday as possible. And if you are planning to come back to Pakistan, it makes sense to start thinking about moving back some time in your mid-40s, when you have had time to enjoy your peak foreign income, and if you moved to the Gulf, you should set a hard stop at age 50 for the time you need to leave the GCC.

It so happens that around the time one hits one’s 40s is when most people’s parents get to the age where they need their children around. In the words of NYU professor Scott Galloway, one of the most meaningful things you can do in your life is to give your parents a good death. If you are sitting outside Pakistan reading this while your parents reside far away from you in Pakistan, think about what that is worth to you as you contemplate where to live.

This article was updated with new data and analysis on 21st March, 2024.

Comments are closed.

One question that comes up is whether someone moving back to Pakistan would have his/her children around them with the kind of political-economic mess we are creating – if the children have a chance(esply if they have the foreign nationality) then it is least likely that they would stick around in these conditions so one might be moving back but would the children moving back stick around?

This specific seems to be definitely excellent. These very small facts are produced using wide range of qualifications know-how. I favor the idea a good deal

Thank you so much for taking the time to put it together and preventing me from having to learn the correct way the hard way.