Many people changed their phone security settings when the ride-sharing company Careem reported a data breach last month. Hackers stole the app users’ personal data like names, email addresses, phone numbers and trip history, according to the company.

Nobody lost their money because of the data breach. Yet it was a big deal for the company and its app users because data has now become as valuable as money.

Businesses make money off stolen data. They buy it to know the spending pattern of their target market and devise their strategy accordingly.

But imagine a situation where data theft has been going on in real time for years on end. Imagine an industry where some players use stolen data to make millions on a daily basis. Imagine a market where thousands of people lose money to a few with access to stolen data while the regulator looks the other way.

Imagine the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX)

It’s one of those anecdotes that stock market people swap in whispers only. They won’t tell you who steals trading data. They won’t tell you who buys that data. What they do acknowledge, though, is that some of the players enjoy an unfair advantage over others because they have access to real-time trading data of individual market players.

They know which broker is buying what stock at which price and in what quantity. It’s like playing a game in which you literally hold all the cards.

The existence of data theft is the worst-kept secret in the stock market. “Why don’t you raise a hue and cry?” I asked one of the brokers who complained of being a victim of market manipulation through stolen data.

“You think I can furnish watertight evidence of data theft? Doesn’t the regulator already know it’s happening? Why should I bear the onus of proof and risk everything I have?”, said he. Plus, an unsuccessful attempt to expose this practice can practically ruin the brokerage of the whistleblower at the hands of the data thieves.

“The SECP [Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan] conducted detailed inspection in relation to rumours regarding data leakage and the PSX has implemented various measures to bolster data integrity based on recommendations,” a spokesman for the apex regulator of the capital markets stated in an email to Profit.

The framing of the answer is interesting. The SECP doesn’t deny that data leakage is taking place. It only says it has conducted a “detailed inspection” but doesn’t say what its outcome was.

Speaking to Profit in a wide-ranging interview in his seventh-floor office in the PSX complex on I.I Chundrigar Road, newly appointed CEO Richard Morin, a McGill-educated Quebecois Canadian, said it was ‘reasonable’ to believe that there might have been issues like that. “I’m not saying there’s nothing. We have an expression in French: there’s no smoke without fire,” said the Canada-born head of the demutualised and integrated stock exchange.

“We’ve spared no resources – human and financial – in addressing this issue. We’ve worked internally; we’ve worked with an audit team of the SECP; we’ve worked with more than one external auditor addressing this issue. It’s a top priority,” he said.

He also hinted at the possibility of data leakages taking place through ‘other potential sources’. “If the information is available, where does it come from? It could come from brokers; it could come from other organisations in Pakistan,” he added.

From within?

Some of the brokers are of the view that the source of data leakage is within the PSX, specifically the IT department. But others disagree, saying it’s difficult to steal data from the PSX building in the presence of strict monitoring.

In a background conversation with Profit, a senior official of the PSX stated that the origin of stolen data appears to be the back-office vendors of brokers with access to their database servers. “There’re no eligibility criteria for back-office vendors. They should have been brought into the regulatory framework long ago. These vendors must be approved by the regulator like other similar service providers,” he said.

“Brokers used to send me other people’s trading data almost every day,” said one former portfolio manager at a larger asset management company, based in Karachi, who wished to remain anonymous. “They do it mostly to curry favour. The more you pay in broker fees, the more data you get from them. They get it from the PSX and from the CDC at the end of the trading day, when trades are being sent in for settlement.”

In many ways, the issue of data theft is perhaps a more brazen way of trying to gain an unfair market advantage that is not altogether uncommon even in advanced markets. Both the New York Stock Exchange and the NASDAQ, for instance, allow high-frequency trading firms place their servers right next to the stock exchange servers in order to reduce the microseconds that it would take a trade order to travel through the wires from Midtown Manhattan to the servers across the river in New Jersey.

The trading firms pay a hefty fee for this right, and are in turn able to gain extraordinary visibility into the orders being submitted by large institutional investors, and effectively “front run” them, making money in the process. This phenomenon was documented by author Michael Lewis in his 2014 book Flash Boys.

Low investor participation

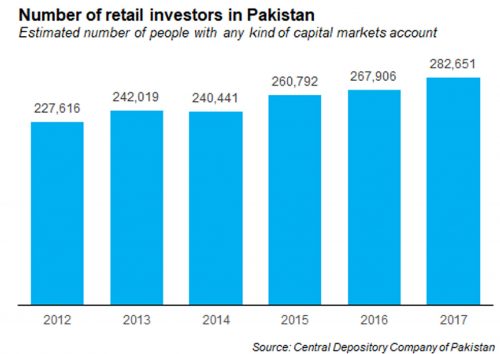

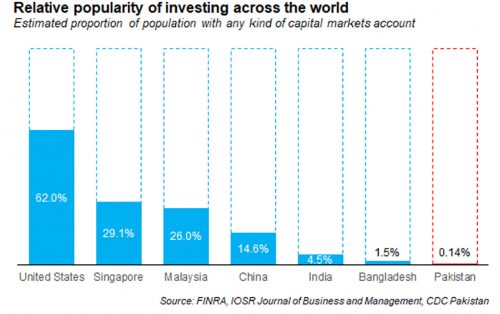

Alleged data theft is one of the many reasons that keep retail investors away from the stock market. The approximate number of retail investors – individuals who trade shares for their personal account – is in the vicinity of 280,000, according to data from the Central Depository Company of Pakistan. That’s only a fraction of what it should be, given that Pakistan has a population of 207 million people. With a smaller population and a comparable per capita GDP, Bangladesh has 2.5 million investors, nearly 10 times the number of people investing in the PSX. As a proportion of the total population, only 0.14% of Pakistanis have any kind of investment in the capital markets, compared to 1.5% of Bangladeshis, and 4.5% of Indians.

The comparison with Bangladesh is made especially surprising by the fact that the Karachi Stock Exchange, the largest predecessor of the Pakistan Stock Exchange, was founded in 1949, a full five years before the Dhaka Stock Exchange, which was founded in 1954. Incidentally, one of the first listed companies on the exchange, the Karachi Electric Supply Company, is still listed on the PSX as K-Electric.

So why do people in Pakistan hesitate to invest in the stock exchange? Morin believes the perception among investors about the possibility of being ripped off lies at the centre of the whole issue.

“I think the perceived investor protection issue is a major, major stumbling block,” said he.

He says the objective of the brokerage community should be to take the number of retail investors to four million in the longer term. Morin joined the PSX three months ago. By the end of his three-year term, he expects to grow the number four times to a million retail investors.

A difficult economic equation for brokers

That goal of increasing retail investor participation may be a difficult one to achieve, in part because it would involve changing both the culture and the economics of the business of equity brokerage in Pakistan.

Consider the following facts.

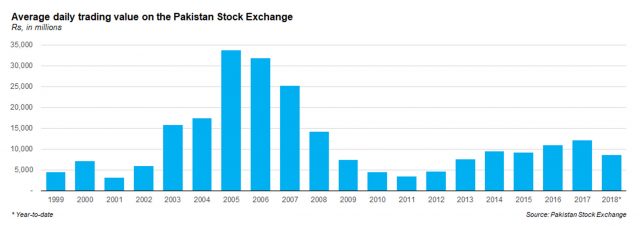

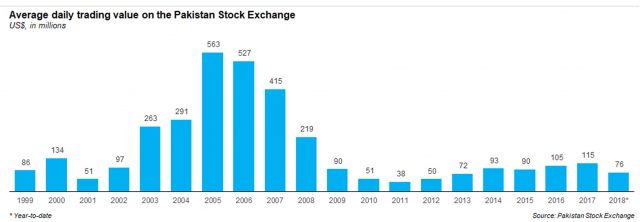

There are 394 entities with trading rights entitlement certificates (TRECs), of whom the PSX estimates 228 are active in the brokerage business, who are all competing to earn commissions on trading activity that takes place on the stock exchange. The total value of trading on the PSX in 2017 was just over Rs3 trillion. That may sound like a lot of money, but brokerage fees in Pakistan tend to be very low.

In fact, most estimates suggest that brokerage fees in Pakistan amount to no more than 10 basis points (a basis point is one-hundredth of 1%) of the total value of shares traded. Assuming two-sided commissions on every trade (both the buyer and seller have to pay their respective brokers), that puts the estimated total value of brokerage fees paid in Pakistan to just Rs6 billion ($57.5 million) in 2017. That revenue has to be split among all 228 active brokerage firms.

That money is not nearly enough. The PSX requires each brokerage firm to have at least Rs50 million ($430,000) in paid-up capital to have a TREC. And that value is actually down from the days when the only way to get a TREC was to buy one from an existing TREC holder. Back then, TRECs used to routinely sell for north of $1 million, and in the pre-2008 crisis era used to sell for as much as $2 million.

If a company has to have half a million dollars in capital to compete against 228 other companies for a market for equity brokerage that is less than $60 million (or about $0.26 million per brokerage), that is not a very attractive business to be in at all. Total costs would have to be less than Rs15 million (about $0.13 million) in order for the business to even remotely approach being an attractive one in terms of return on equity. And it is next to impossible to run a brokerage firm on that little.

Some of the bigger brokerage firms obviously earn a substantial amount of revenue from their retail brokerage operations, but even the largest ones cannot hope to cover their operating costs on brokerage revenues alone. And the smaller ones do not have a snowball’s chance in hell of making a living on serving retail investors.

So then why were TRECs worth so much? Because just earning commissions on facilitating client trades is not even remotely close to being the most important way brokerage firms make money in Pakistan.

The real money spinner for brokerage firms is their proprietary trading activity, where brokerage firms buy and sell shares using their own money. And here, it appears that illicit tactics are a commonly used tool to make money.

In an academic research paper published in 2005 in the prestigious Journal of Financial Economics, economists Asim Khwaja, a professor at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, and Atif Mian, then a professor at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business and now at Princeton University, argue that one of the biggest ways brokerage firms in Pakistan make money is through a technique known as “pump and dump”.

“How costly is the poor governance of market intermediaries? Using unique trade level data from the stock market in Pakistan, we find that when brokers trade on their own behalf, they earn annual rates of return that are 50-90 percentage points higher than those earned by outside investors. Neither market timing nor liquidity provision by brokers can explain this profitability differential. Instead, we find compelling evidence for a specific trade-based ‘‘pump and dump’’ price manipulation scheme: when prices are low, colluding brokers trade amongst themselves to artificially raise prices and attract positive-feedback traders. Once prices have risen, the former exit leaving the latter to suffer the ensuing price fall. Conservative estimates suggest these manipulation rents can account for almost a half of total broker earnings. These large rents may explain why market reforms are hard to implement and emerging equity markets often remain marginal with few outsiders investing and little capital raised,” write the two economists in their paper.

By now, the culture of proprietary trading is endemic at the PSX and trying to get brokers to change their behaviour and chase after retail investors is likely to be exceedingly difficult. (The popular movie The Wolf of Wall Street depicts a brokerage firm that engages in this kind of behaviour.)

Incidentally, the high incidence of “pump and dump” schemes does not actually prevent long-term retail investors from reaping highly attractive returns.

The benchmark KSE-100 index has risen by an average annual rate of 21.5% per year for the last 20 years. In absolute terms, this means that Rs1 million invested in a fund that matches the performance of the KSE-100 index 20 years ago would be around Rs49 million today. For foreign investors thinking about the effects of currency devaluation, the KSE-100 index has had an average annual return of 16.1% in US dollar terms during that same period. A foreign institutional investor who invested during that same period, using an index-tracking strategy, would have had $19.6 million in 2018 for every $1 million invested in 1998.

A slow start to the change of guard

Brokers anticipated a surge in turnover – the number of shares traded on the exchange – when a consortium led by Chinese investors, led by the China Financial Futures Exchange Company, acquired a 40% share and management control in the demutualised PSX at the end of 2016. Before that, the exchange had been 100% owned by the brokerages. One of the objectives of demutualisation was to separate ownership and trading rights. This was supposed to ensure transparency in trading while allowing the foreign investors who bought shares – and management control – to focus on product development.

But after rising slightly in the first year following the acquisition, the total value of shares traded on any given day has dropped significantly after the acquisition of the strategic stake by Chinese investors. Fewer shares now change hands on the exchange than earlier. There’s also a perception among market participants that there’s been zero improvement in terms of the IT infrastructure. The acquirer has yet to introduce any new products. In short, foreign investors have done little that local investors couldn’t have done.

Some observers may liken the evaporating volumes to the slow death of retail brokerage, but Morin calls it a ‘transformation’. It started with the integration of the stock exchanges of Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad, he says. As a result, the number of stockbrokers went down from 400 to 228. “One thing we can say is that (retail brokerage) is not growing at the rate that it should be growing,” he admits.

Here’s a little insight into the turnover trend on the PSX. The average emerging market has a turnover ratio of around 55 percent. It means the value traded on the exchange during the year is 55% of the market capitalisation, or the total value of listed companies.

Illiquid markets have a lower turnover ratio while speculative or unsustainable markets have a higher one. (The turnover ratio of the Pakistani market was 300% just before the 2008 crash.) Currently, it is in the range of 35-40%. There’d be a bunch of happy brokers if the turnover ratio was to rise up to 55%. In percentage terms, such an increase will herald a growth of about 60% in the brokers’ business.

The PSX CEO wants to increase turnover organically, i.e. in line with the rise in the number of retail investors.

But an increase in retail participation is linked to the perception about the lack of investor protection – a view that’s validated by frequent bankruptcies by brokers.

“We have to reduce the number of broker defaults in Pakistan,” he said. There was no default last year. But a number of brokerages ran away with investors’ money prior to that.

On average, two brokers went bankrupt every year in the past 20 years. Every time a broker went bankrupt, between a hundred and a couple of thousand people would lose money. That left a direct impact on the perception about the stock market. “We have an unenviable track record. (But) it’s improving considerably… The risk of broker default has already gone down considerably,” he said.

On the one hand, the regulatory framework has gradually been improved. On the other hand, the number of brokerages has reduced substantially in the aftermath of demutualisation. The risk of a broker going bankrupt has gone down because many of the weaker ones have already gone bankrupt. “The average broker is bigger today and better structured than it was two, three or four years ago. By no means am I saying the problem is over. I’m saying that the problem is easier to address today,” he added.

But the detractors of the PSX CEO claim he’s deliberately overplaying the broker default issue because he has little progress to show on the front of business development, which is the primary responsibility of the exchange CEO post-demutualisation.

According to PSX data, 85% of almost 11,000 complaints registered between November 2008 and March 2017 have already been settled. More than 57% of investors received 100% of their approved claim amount while the rest were compensated as per the weighted average method.

In addition to trying to minimise the risk of a broker default, the PSX management is also proposing the reform of its investor protection fund, which has Rs3 billion to help investors if their broker declares bankruptcy.

Under the disbursement mechanism currently in place, the fund cannot utilise more than Rs25 million to reimburse affected investors should their broker go bankrupt. “We want to remove that limit. When a broker goes bankrupt, there should be no limit. (The exchange) should be able to use the total amount in the fund. The limit will be on the per-client basis,” he said, noting that the final figure will be at least Rs1 million per client per broker. “So now we’ll be in a position to go to retail investors and tell them to invest in the PSX: your money will be as safe as with a savings account.”

But some senior members of the PSX management have raised objections to the proposed mechanism. While the suggested changes will help small investors get a better deal, bigger investors are likely to lose out because of the per-client limit, they say. The existing mechanism ensures half of the settlement amount is disbursed on the weighted average basis – a feature that ensures reimbursement proportionately.

This technique has been used in advanced markets in the past: in 1970, the United States government created the Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC), which has a similar, broker-funded investor protection fund to help investors recover their money. Unlike Pakistan, however, in the United States, the SIPC is allowed to borrow from the US Treasury if the fund falls short of covering the amounts it needs to return to investors.

Despite loud pronouncements about the importance of investor protection by the PSX management, the position of chief regulatory officer (CRO) has remained vacant for the last year and a half. This position is statutory, like that of the CEO or company secretary. The CRO position is unique to the PSX, which happens to be one of the four self-regulatory organisations (SROs) operating in the capital market. The other three SROs are the Pakistan Mercantile Exchange, Central Depository Company and the National Clearing Company of Pakistan.

Morin says the delay in the appointment of a full-time CRO is deliberate on part of the PSX. The exchange expects the apex regulator to pool the resources of t

that the new entity will have its own resources, such as auditors, investigators, and adjudicators.

But the exchange will keep a part of its regulatory division. “We’re not exactly sure what’s going to go where. But I must reassure you that we have very senior positions in our regulatory affairs division (RAD). Rest assured, our RAD is well looked after,” he said.

Skeptics are wondering if the proposed move will add another layer of bureaucracy in the capital market. After all, the new entity will only send orders. The enforcement function will continue to rest within the PSX.

Introducing ETFs to Pakistan

In his many public speeches since taking charge, the PSX CEO has repeatedly vowed to introduce investment products on the exchange designed specifically for retail, non-savvy investors.

He’s targeting those 40-50 million members of the Pakistani middle class who have money to invest but lack knowledge about the stock market. He specifically mentions exchange-traded funds (ETFs), a product that ordinary investors can buy and sell on the exchange just like a typical stock.

But unlike a stock that symbolises the ownership in a single company, an ETF represents the value of a number of listed companies. Like a mutual fund, an ETF allows investors to have exposure to a large number of listed companies through a single transaction. Investors benefit from any price appreciation and dividend declaration from the constituent companies.

Morin wants ETFs to be listed ‘as quickly as possible’ because it’s an ‘easy, accessible investment vehicle’. It’s safe – a key consideration for retail investors – because it’s a trust similar to a mutual fund.

“We’re reorganising the PSX to devote human and financial resources specifically to this project,” he said.

An ETF listing requires two players other than the exchange. The first player is called an issuer, which is usually an asset management company (AMC). At least three AMCs have shown interest in becoming the ETF issuer, according to Morin.

The second player is called an authorised participant (AP), which is usually a broker.

Let’s assume that an asset management firm intends to introduce an ETF that consists of the 30 shares of the KSE-30 Index. Like a mutual fund, this ETF will be a trust that will hold the shares in the same proportion as the KSE-30 Index. The role of the AP (or the broker) will be to acquire those shares from the open market and deliver them to the issuer (or the AMC).

In return, the AMC will create a unit of the ETF and deliver it to the broker. “Nobody has stepped up for the role of the AP so far. Some are interested. But they don’t have the expertise. They don’t know the business. It requires capital. There’re risks involved,” Morin said, noting that the challenge with the ETFs lies mostly in structuring the AP business.

He suggested that listing an ETF may require a transfer of expertise from a developed country. It may also require an injection of capital, he said. “It’s a huge undertaking. We intend to do it within 2018.”

Streamlining processes and other reforms

In its attempt to attract retail investors, the PSX management is pushing for streamlining account opening and know-your-customer processes. It currently requires 32 signatures to open an account despite the fact that electronic signature is legal in Pakistan.

“The process is paper-based and very cumbersome. I want an investor to be able to go through the account opening process in 15 minutes. I think we need to arrive in 2018 in terms of technology.”

Morin also vowed to ‘completely replace’ the Karachi Automated Trading System (KATS), the online share trading platform, which is known for its limited features and a general lack of user-friendliness.

This new trading platform will support not only equities but also futures and options. The PSX has issued a request for information, the first stage of the procurement process. It expects to receive the new platform by early 2019. “If there’re data leakage risks within the trading system, it’ll eliminate them,” he said, while declining to talk about the expected cost of the system.

Unlike most people from his part of the world, Morin enunciates his words slowly and carefully. Perhaps he was advised to speak slowly so his Pakistani colleagues could understand him better. He banters with reporters and cracks self-deprecating jokes. Yet his hearty laughs seem to have won him few friends among the brokers’ community so far.

“He’s yet to hold his maiden meeting with the brokers, although he’s been here for months. The impression is that he’s unapproachable,” said one broker requesting that his identity shouldn’t be disclosed.

Perhaps the impression was reinforced when the PSX management allegedly went on a ‘firing spree’. At least two general managers were shown the door along with senior employees from the IT department.

Morin recently conducted a two-day annual strategic planning exercise at a Karachi hotel with senior members of the PSX management. The brokers objected to the ‘lavish’ offsite meeting, saying that the exchange, which is a listed entity itself, should cut its expenditures amidst dwindling earnings. Net income of the PSX for the nine-month period through March dropped 55% year-on-year to Rs65.5 million.

“The brokers’ community is, I’d say, half right. There’s been no comprehensive meeting with all of them,” he said, adding that there’ve been forums where he met brokers individually or in groups. “I’d say not a week goes by without my meeting three, four, five brokers. Sometimes individually, sometimes in groups. I’ve never ever once refused to meet a broker. I’ve never said I’m too busy.”

As for holding an off-site meeting, Morin said it was to ensure that people didn’t run back to the office during the exercise. “At the last minute, we decided to do it downtown Karachi as opposed to a remote place because I needed to be in Karachi that Sunday,” he said, emphasising that the only body to which he’d justify himself was the PSX board of directors.

In a similar unapologetic vein, he said some of the senior PSX employees left because the exchange needed transformation to achieve its ‘very ambitious objectives’ in the next three years. “I’d hope that you talk at least as much about the people we’ve hired than the people who’ve left the PSX,” he said, adding that the board of directors has accepted a new organogram for the exchange.

The PSX is hiring a chief operating officer besides a head of marketing and business development – a position that doesn’t currently exist. Under that head will be specialised teams tasked with attracting new listings and retail investors. The PSX is also hiring a head of product management and research who will oversee the resources dedicated to ETFs.

“We’ve set an objective for 20 new listings a year 2018 onwards. These are just equities, not debt listings,” he said.

Morin can deploy high tech monitoring system and IT system apart from auditors to find those involved in data theft and get rid of them forever. A lots of chances are required to modernised PSX. Not only ETFs, option trading, futures and index fund need to be introduced as soon as possible. Chinese can replicate products from Shanghai/Shangen exchanges.why they are waiting so long. This is reality, I don’t see any visible change in PSX rather they loosing ground.

I think Morin should implement new platform for trading like Metastock/Amibroker, even Bangladesh has Amibroker and better tools for trading. The PSX trading platform is soo old school; i hope Morin would bring it close to the other developed countries.

Cheers.

a new paltform treading like.

Comments are closed.