Amir Jahangir’s family has been in the textile and cotton business since the pre-Partition era, during which time they have had to completely shut down their business and started again from scratch three times.

Before Partition, his family had a textile business in Calcutta, which they had to let go when they migrated to Pakistan in 1947. After Independence, they set up another textile business in Dhaka, which they had to abandon when East Pakistan separated from its western wing in 1971.

The third death and rebirth of the family’s business came in 1987, while Amir was still enrolled in Lahore’s Aitchison College, though this time, it was purely for economic reasons. His father had set up a spinning mill known as Taj Textile Mills, which ran into difficulties and had to be shut down. “It is a very difficult thing to run a manufacturing company. We had cash flow problems. And at the end of the day you need a lot of cash flows to run a spinning mill,” he said, in an interview with Profit.

Such problems in the cotton value chain are not uncommon in Pakistan and over the years numerous cotton millers have gone out of business and cotton farmers are increasingly switching to other substitute crops like wheat and sugarcane that offer better returns.

However, Jahangir seems to have found a way around this. Instead of focusing on manufacturing, in 2007 he decided to venture into cotton trading instead and today his cotton brokerage house handles almost 3% of Pakistan’s total cotton produce. “In the whole season we trade around 400,000 cotton bales, the value of which comes down to roughly Rs12 billion,” he says.

Many millers then switch over to trading, which, while rational on their part, has the perverse economic effect of taking investment out of Pakistan’s manufacturing capacity and into commodity trading, further weakening the overall competitiveness of Pakistan’s textile manufacturing as a whole. This also has the effect of significantly increasing the market power of traders over both growers and manufacturers, which in turn further continues to skew the incentives.

Traders perspective

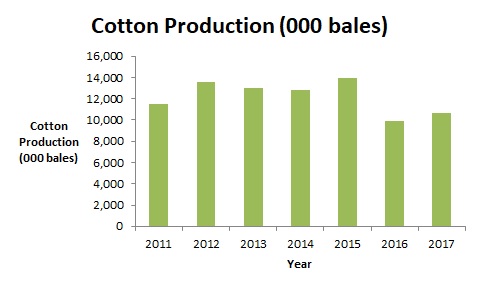

Pakistan’s cotton production, which peaked at close to 14.5 million bales per year, has fallen down to around 11 million bales this year, owing to a variety of factors, though like all good textile professionals, Jahangir blames the government.

The mills usually exercise significant market power over the ginners, and generally have an upper hand in price negotiations because they are the buyers. However, cotton brokers like Jahangir, who buy from ginners and sell to mills often are able to extract outsize pricing from the mills as well. “For example, if a broker is selling 2,000 bales, which cost Rs35,000 to Rs36,000 each, and only charges Rs100 extra per bale, then he can easily earn Rs200,000 extra,” he says.

Similarly, small spinning mills also have an inherent disadvantage compared to larger mills. According to Jahangir, even the big profits made by large spinning mills are not primarily manufacturing profits but are trading profits. “Only people operating large spinning mills can survive in this industry, as they earn a trading profit over and above their manufacturing profit. The banks give [high credit] limits to the big mills, who then buy the amount of cotton that they need for the whole year in one go, which pushes the cotton market up. In comparison, small mills who buy cotton on a daily basis lose out and their average cost of the cotton becomes uncompetitive. Everybody can earn a manufacturing profit, but there is a limit to how much you can save in manufacturing,” he says.

A large number of spinning mills have recently shut down in the country, under the burden of rising costs. According to Jahangir, the number of mills that have shut their doors is as high as 40. “Spinning is a business which, if shut once, is very difficult to set up again. Recently, more than 40 mills have closed down.”

Jawad Asghar, the Chairman of the Pakistan Yarn Merchants Association, who heads the biggest yarn market in the countries textile hub, Faisalabad, also paints a bleak picture of the countries textile industry.

“More than 50% of all the yarn produced in Pakistan’s spinning mills is sold here in the Sutar Mandi (yarn market). So this is such a big market,” he informs.

“However, our export has fallen. We used to sell our yarn to China and other countries which has ceased now, due to which the local market has come under pressure. There is excess domestically produced yarn in the market and even then we are importing yarn from India and China as their yarn is cheaper than ours,” he says.

Why? “The electricity and gas in China and India are cheaper, their raw material is cheaper, the government gives subsidies and rebates, which means that the prices of the yarn produced by China and India are cheaper, hence making our yarn uncompetitive.”

“The same goes for farmers. Their costs have also increased. Urea (fertilizer) used to cost Rs1,200, now it has increased to Rs1,700.”

Javed, another trader in the same Sutar Mandi also blames the falling textile exports. “The Afghanistan border is blocked, due to which textile produced in Pakistan, just ends up in warehouses. Exports to other countries has also fallen considerably,” he says.

The cotton crop

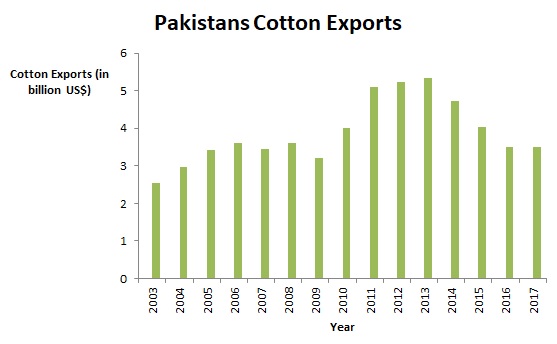

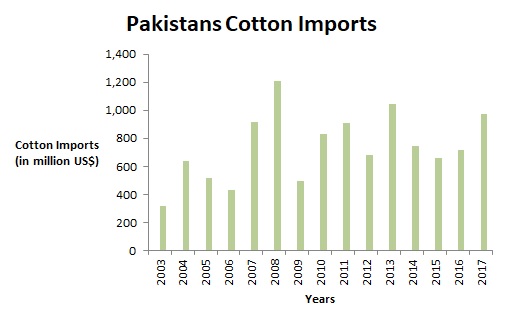

Pakistan is currently the fourth largest producer of cotton in the world after China, India and the United States. However, Pakistan’s cotton production has been falling in recent years. Over the last five years, cotton production has experienced a decline of almost 14%, falling from 13.86 million bales to almost 11.98 million bales. Similarly, cotton exports have fallen from more than $5 billion in 2012, to $3.5 billion by 2017. During the same period the imports of cotton have increased from around $700 million to $974.98 million.

The import of cotton is further expected to increase with the government considering removing the 5% customs duty on its import. “The price of the imported cotton will decrease which will lead to a reduction in domestic cotton prices, impacting cotton farmers adversely, as the price of the domestic cotton is very closely related to the price of cotton internationally. If the price of domestic cotton is higher than that internationally, the textile mills will switch to imported cotton,” says Bilal Israel, a cotton, wheat and sugarcane farmer based in the Rahim Yar Khan district. However, he says that the said decrease in custom duty will positively impact the mills as they will be able to buy their primary raw material, cotton, cheaper than before.

One of the reasons for the declining cotton acreage is the eroding economics of the crop. In recent years, cotton has been losing growing area to other crops that either have better economics like corn or maize or are provided support prices like wheat and sugarcane. The All Pakistan Textile Mills Association (APTMA) estimates that Pakistan has had a 27% decline in cotton production, which includes a 17% decrease in area under cultivation since the 2014-2015 growing season.

“Why will the farmer grow cotton if there is no manufacturing industry present for it? He will not be able to sell cotton at a feasible rate and will naturally move towards economically feasible substitute crops,’ says Javed, a yarn trader in the Sutar Mandi.

On the other hand, the sugarcane crop needs lots of water and farmers are able to use water from a canal system which they get at heavily government-subsidised prices. Hence the total input costs for the sugarcane crop becomes economically competitive compared to other crops. “This is one of the reasons that people are shifting to sugarcane,” says Bilal Israel.

However, the recent Khareef season has been bad for Bilal and even his sugarcane crop has taken a hit. “We get water from the Abbasia canal that comes out of Panjnad. On the way, it crosses Cholistan, over where landowners steal water from the canal and the water doesn’t reach us. This time I have had practically no production of cotton or sugarcane due to shortage of water. Their were approximately 106 illegal outlets in the canal,” he says.

“The agricultural downstream in the Rahim Yar Khan District has been effectively destroyed. In Rahim Yar Khan, the share of water from Abbasia Canal is 1,900 cusecs but we are getting only 554 cusecs. My personal crops of cotton are so bad that some of the cotton fields have not afforded a single picking despite putting in every possible effort and investment.”

Another reason for the decrease in cotton production, according to APTMA, has to do with a 12% drop in per acre yield of cotton, since 2014-2015. On the other hand, yields in the Indian Punjab are almost 50% higher, compared to the Pakistani side of Punjab. Why? Because over the years, Pakistan has failed to invest into seed research.

Currently, over 97% of the cotton grown in Pakistan is first-generation genetically modified pest-resistant plant cotton (also known as BT cotton). However, this first-generation technology first entered Pakistan around 2005-2006, through piracy and illicit means and without proper stewardship from the technology provider. As a result, the BT characteristics lost efficacy after a few years, and crops became resistant to it and Pakistani farmers were unable to fully benefit from it.

“It’s like buying a fake copy of Microsoft Windows. If you do that, you will not get any updates. You have to have proper measures through which you manage crop resistance. Over time the crops become resistant to the BT characteristics. It is a natural phenomenon. Companies that own the technology have specific measures and strategies in place so that the resistance does not develop very quickly,” says an agricultural expert who works at a large multinational agricultural technology company while talking to Profit on the conditions of anonymity.

In comparison, BT cotton has brought about a revolution world over and added to cotton yields, productivity and farmer profitability. Internationally, the third generation BT technology has been launched, whereas poor enforcement of intellectual property laws make it impossible for BT cotton technology providers to enter the market in Pakistan.

“There was no ownership, no education for the farmer and it did not have proper monitoring. And there is no protection for intellectual property in Pakistan. When the first generation BT cotton was illicitly bought into the country in 2005-2006, everyone was able to steal it and use it. Hence, technology providers are reluctant to enter the market, despite Pakistan being the fourth largest cotton producer, as there is no way for them to ensure that they will be able to capture value,” said the agricultural technology expert.

Quality matters

It’s not only the quantity of cotton produced that is the problem in Pakistan, but the quality lags behind as well. Even if the cotton production increases, Pakistan will still have to import long staple cotton that the textile industry needs to produce premium products. “Why is India’s cotton better than ours? Why do we import from India? Because we cannot produce long staple cotton as we have never properly invested on cotton seed research,” says Amir Jahangir.

Quality of cotton hinges on the seed variety. Seed variety breeding programs have been compromised and therefore new varieties with requisite fiber characteristics have not been introduced. “Not a lot of people are investing time and money in breeding good variety cotton seeds that are demanded in the market. Traditionally, there were farmer breeders as well who used to create and release their own seeds. But again there was no protection of intellectual property. The government should focus on strengthening intellectual property laws and especially focus its effort towards operationalizing the newly enacted Plant Breeders Rights Act 2016 which will incentivize the public and private sector researchers to develop newer and better cotton seed varieties,” says the agricultural expert, again commenting on the condition of anonymity.

“Nobody will invest into research if they know that we will develop something and as soon as they will release it, someone will copy it.”

Raw cotton quality is also compromised due to traditional cotton-picking practices and post-harvest handling. “During the post-harvest handling and transportation trash gets accumulated in our cotton which contaminates it. One of the reasons is that we do not use proper equipments and rely on hand picking.”

While farmers and small millers take a hit, people at the top of the cotton value chain are still making good money. Amir Jahangir claims that the trading volumes for his cotton business are growing by an almost 30 per cent every year. However, if the decrease in cotton production continues and government policies remain non-existent or biased in favour of other crops, it is highly likely that this growth rate will become unsustainable in the future.

Serious issues regarding cotton related items

Comments are closed.