German philosopher Friedrich Neitzsche once said, “Many are stubborn in the pursuit of the path they have chosen, few in pursuit of the goal.” It may be early days yet, but it does seem that Jazz CEO Aamir Ibrahim may be among the latter few.

It is no secret that it is becoming harder and harder to grow a business the mobile telecommunication sector in Pakistan. Teledensity has already hit 74%, with more than 154 million active mobile subscribers in the country, so growing revenue by adding more users rapidly is becoming less and less of an option.

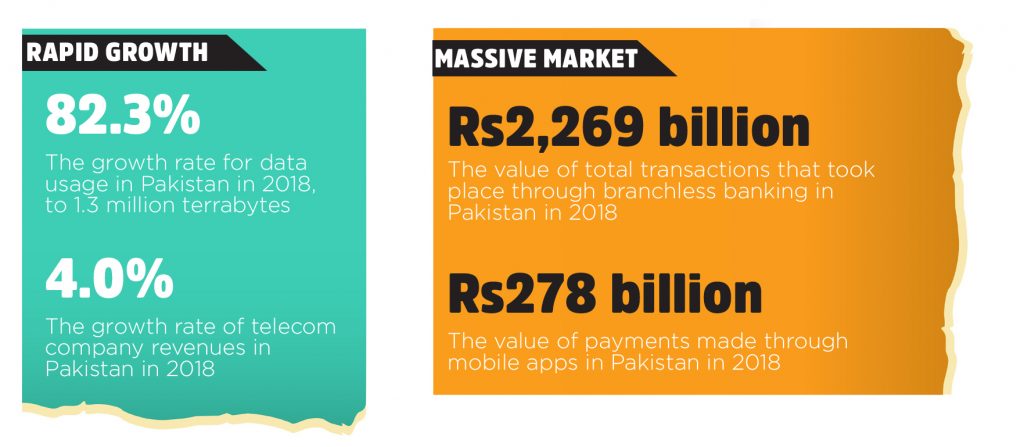

The industry’s revenues have been growing at a snail’s pace for the last few years, at least by the standards of Corporate Pakistan. Total revenue for the industry was Rs489 billion in the financial year ending June 30, 2018, the latest for which complete figures are available from the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA), up just 4.0% from the previous year, only marginally above inflation. And 2018 was an improvement over the previous year, when revenue for the industry grew at just 1.5% over the previous year.

And with a 36.7% market share, the largest, Jazz has the added challenge of being the biggest player in the industry and thus having the least room to grow by taking share away from its competitors. In other words, Aamir Ibrahim has probably the toughest job in Pakistani telecommunications: little room for upside, plenty of room for downside.

So how does an ambitious CEO grow his business that is already the biggest in its sector? He can start, as Ibrahim did, by looking at what he can grow, even if it is a small segment of the market to start with.

Veon: building the WeChat of Pakistan

The two areas of Pakistan’s telecommunications market that have been growing at rapid rates are mobile internet, and mobile banking.

Of the 154 million mobile phone subscribers in Pakistan, just 54.1 million have access to mobile broadband internet, defined as 3G or 4G data subscriptions as of June 2018. That number grew by 33.3% over the previous year. And actual data use is skyrocketing. Total mobile data usage rose to nearly 1.3 million terabytes in fiscal 2018, up 82.3% from 2017. That comes to approximately 1.9 gigabytes per user per month.

But while that business is growing rapidly, it is not directly translating in revenue growth for the mobile telecommunications companies, in large part because the increased internet usage is cannibalising from some of the voice and texting revenue for the mobile companies.

It is in part to combat that cannibalisation that Jazz – the company formerly known as Mobilink – launched Veon, a multipurpose app that it hoped would become Pakistan’s version of WeChat in October 2016.

At the time, Jazz’s management was deathly afraid of becoming just another utility company, focused on providing the low-value, high-cost telecommunication infrastructure that would undergird other companies building high-value, low-cost apps and other businesses that would create significant shareholder value for their owners. By not participating in competing for that app space itself, the Jazz management felt that they would effectively be leaving money on the table.

“We are not going to be in the do-nothing category,” Aamir Ibrahim had said to Profit in a 2017 interview. “Traditional telcos have made money mainly from voice but didn’t do any innovation except SMS, but OTTs [over-the-top apps] did that and surpassed us in that space. It’s not about being bigger, it’s about being better.”

Veon was launched as an all-purpose app where users could do almost everything using mobile phone like news feeds and self-serving mobile top-ups and cellular bill payments. It was a bold move by the company to step into a territory dominated by the likes of WhatsApp in messaging, and the banks and its main rival Telenor in the payments space.

The app would primarily make money the way any other app makes money: gain a high number of users who are attracted to the product, and then sell them services as well as gain revenue through selling ads on the platform.

Aamir knew the risks back then too. In his own words at the time, “The risk of not taking this risk [launching Veon] is much higher.”

Had Veon succeeded in becoming the WeChat of Pakistan, as was hoped by Aamir and his team, Pakistan’s telecom market would have undergone a quick and massive transformation. Free texting and voice services, coupled with financial services and self-services platform provided by Veon would have eaten up the call and text revenues of all mobile SIM services including Jazz’s, which according to Aamir, “It is still better to cannibalize yourself than have someone else cannibalize you.”

However, two years down the line Veon failed to live up to its expectations.

Why Veon failed

There is one very simple reason why Veon failed to become the super app of Pakistan: because Pakistan is not China.

In Silicon Valley, when companies are looking to raise money for a business in China, they have a tendency to describe it as the Chinese equivalent of an American company. Baidu is the Chinese version of Google, Alibaba is the Chinese version of Amazon, Didi is the Chinese version of Uber, and WeChat is the Chinese version of Facebook.

Have you noticed how nobody talks about the Pakistani version of these apps? The Pakistani version of Google is Google. The Pakistani version of Facebook is Facebook. And yes, while Careem is a strong competitor to Uber in the Pakistani market, Uber itself is present and growing its business in the country.

This, by the way, is not a phenomenon limited to Pakistan. India does not have a rival to Facebook or Google either. The Indian version of Google is Google. Yes, Flipkart and Ola are strong competitors in their respective markets, but there is no Indian competitor to Facebook either.

If a service can exist as a completely global platform without the need for significant local customization, as internet search, social media, and messaging can, then the global incumbent is likely to dominate in the local market as well.

The only reason China is different is because China actively bans foreign competition and then allows local companies to build up rivals within the confines of a tightly government-controlled internet infrastructure. That requires a level of authoritarianism that Pakistan, thankfully, does not have, and as a result Pakistan’s internet environment is much freer than that of China.

What that means, however, is that if you try to create a “Pakistani version” of something that already has a dominant global user base that includes millions of Pakistanis, it will likely fail. What Jazz had hoped, however, was that while Pakistanis have a multiple apps that perform all of the functions of a super app, they might appreciate having it all in one convenient platform.

It was a valiant effort, but it ultimately failed.

The app had some initial success, with 2 million downloads, though 1 million of those were within the first three months of the app’s launch. Aamir Ibrahim admits that the overall response they received was not up to the management’s expectations. The company realized that not only the initial platform of the Veon app was not strong enough, but they had also tried to do too much and add too many things in a single app.

Part of the struggle, of course, was the fact that the social and messaging element of the app was directly competing against WhatsApp and Facebook, both owned by the largest and most powerful social networking company in the world, and one that already had as its users virtually every Pakistani with a mobile internet connection. Why switch to Veon when everyone you know is already on Facebook and WhatsApp?

And then there were some operational challenges. For instance, one of the ways that Veon tried to attract more users to its platform was through a co-branded Black Friday sale with Daraz.pk, offering special discounts on the shopping platform to Veon users. That, however, ran into issues after Daraz.pk went through an ownership change. “Daraz.pk decided not to work with us once they were bought by Alibaba,” said Aamir.

Those operational challenges got scathing reviews from industry players. “Veon’s marketing appears to be making every mistake in the playbook,” wrote Monis Rahman, founder and CEO of Naseeb Networks and Rozee.pk in a Facebook post. In another post, he added “Veon tried hard to reinvent itself as a new high-tech player, in hopes of making money from apps and service commissions instead of classic voice and data subscriptions. It now is cutting management jobs and simplifying its structure as part of a retreat to a more traditional telecom business model. Lots of lessons here.”

Needless to say, all of those challenges meant that Veon simply did not get enough traction to become what Jazz’s management had hoped it would become: the engine of the company’s future revenue growth.

To his credit, Aamir Ibrahim did not let his ego get in the way of dispassionately rational decision-making. When the time came to decide whether or not to pull the plug on Veon, Aamir did not hesitate to admit defeat and cut his losses. It helped, of course, that the retrenchment of the Veon platform was a global phenomenon that Jazz’s parent company Vimpelcom implemented across its subsidiaries around the world.

But that still did not resolve the core question for Jazz: where will the next phase of the company’s growth come from? The answer on that front was staring at the management in the face the whole time.

JazzCash: the unexpected success

As stated above, mobile internet usage is not the only growing category in the otherwise stagnating mobile telecommunications space. There is also mobile banking, specifically mobile payments.

According to data from the State Bank of Pakistan, both branchless banking and mobile payments are a rapidly growing space. The number of branchless banking accounts hit 38.5 million in the first quarter of 2018, up from just 15 million in June 2015. During that period, the total volume of transactions grew by an average of 13.6% per year to 532 million transactions. The total value of transactions grew at a somewhat slower pace, at an average of 7.2% per year to Rs2,269 billion.

The real growth, however, has been in the number of mobile app transactions, which grew at an average of 34.8% between 2015 and 2018 to 15 million. The value of transactions grew by an even faster 37.8% per year during that period to reach Rs278 billion.

What that means is that Pakistanis are increasingly becoming more willing to spend money online. And that is where Jazz is poised to benefit through its branchless banking and mobile app-based payments platform, JazzCash.

What Veon failed to achieve, JazzCash seemed to surpass. JazzCash currently has close to 5 million customers. Aamir said: “We see a lot more traction along JazzCash. We see our customers excited about getting into financial inclusion. So we decided to enrich the messaging platform in JazzCash, instead of trying to bring it all together in Veon.”

It is that willingness to pivot from a flailing platform to investing in a thriving one that is the kind of agility that is often missing in large companies. It is also what tends to keep companies from being able to continue growing their business after having reached a market-leading position.

As with Veon, JazzCash is also available on all mobile networks and not just Jazz subscribers. Approximately 30% of JazzCash customers are not Jazz subscribers. And in Aamir’s words, “Our next big endeavor is propagating this facility [JazzCash] to the masses.”

He said that it is an endeavor to include the unbanked and the under-banked to a financial institution. “We have close to five million customers who use JazzCash on a monthly basis to send remittances, topping up their mobile, paying utility bills, etc. So they have started to use that. This is a big opportunity for Pakistan.”

Financial inclusion is certainly an opportunity for Pakistan. According to the central bank, only about 23% of adults in Pakistan have a bank account. That massive unbanked population is reliant almost entirely on cash, which is not only inefficient and susceptible to theft, but also has the disadvantage of enabling crime and money laundering.

That is where Aamir wants to focus his attention next. “We want people to be banked. We want to eliminate cash and we want to move towards digitalized cash. That also eliminates corruption, and that’s consistent with the government policy and policy of the State Bank of Pakistan. We want to document the transactions. Because when transactions are documented there is a trail and you can eliminate money laundering. We think that Pakistan is ripe for financial inclusion and that is an opportunity that gets me excited,” Aamir said.

He also has elaborate plans to penetrate JazzCash to the urban population, shifting from the traditional focus on rural and suburban areas. “Over the last few years both JazzCash and EasyPaisa have focused predominantly on the suburban and rural communities because domestic remittances were the biggest use case or bill payments were the biggest pain point.” However, now he believes that the urban population also needs to find a convenient method of making payments.

He said, “The urban population is probably also under-banked if they are still taking out their wallents to make cash payments. “We want JazzCash to be the number one option all over Pakistan, whether it is B2B, B2C, or involves government. Our plan is to make JazzCash the de facto payment option.”

To him perhaps one of the reasons that JazzCash still hasn’t gained a lot of customers in the urban areas is that “there are very few places where it is accepted. And that is our second target. We need to onboard a number of merchants where JazzCash is easily accepted. If we expect people in IBA and LUMS to use JazzCash, it needs to work on McDonalds, Gloria Jeans, to pay the tuition fee to LUMS and so on. This is what we are working on now,” he said.

With data and financial services becoming the new cash cow as well as survival strategy for the telecom industry in Pakistan, Aamir’s plans for Jazz seem to be in the right place. And he has all the support from the state for his next big endeavor.

“SBP looks at us as a beacon of hope that can deliver on that national strategy,” he said, while lauding the support his company receives from both the State Bank and the PTA.

That support and success comes at exactly the right time for the company, because the telecommunications industry may be about to go through another round of upheaval.

The spectrum auction, and what comes next

The next generation of spectrum licenses for 3G and 4G are up for renewal in 2019. This means that telecom industry will have to go through a transitional period and players have to be cautious about their current expenditures and focus areas.

“For one, there is a lot of uncertainty about the prices of these licenses, and even if they are lower, the telecom companies will still have to pay hundreds of millions of rupees,” said Parvez Iftikhar, the CEO of ICT Forum, an Islamabad-based think tank, and a member of Prime Minister’s 17-member Task Force on IT & Telecom.

“Voice is going down and data is going up,” he said. “The industry is going towards data and survival will not depend on connectivity alone. The industry is going into applications,” he said, adding that the current government is also serious about IT and there is already a noticeable trend of cash-on-delivery moving towards online payments. “Inclusion of fintech into the telecommunication space is imperative and necessary for the players in the industry to stay relevant.”

Over the past decade and a half, Pakistan’s telecommunication companies have set up an infrastructure that allows Pakistanis across the entire income spectrum to be connected to each other and the wider world, which in turn has created significant economic opportunity for both these companies as well as for the economy as a whole.

Among the benefits from the prevalence of widespread internet access: the ability of apps like Careem and Uber to launch their services in Pakistan, which would not have been possible without the presence of a nationwide 4G network that allows tens of millions of Pakistanis to access the internet at high speeds and low prices.

However, the government has historically looked upon the telecommunications sector as a cash cow, yielding high tax revenues that at one point accounted for nearly one in ten of every rupee collected by the Federal Board of Revenue. At a time when the industry is struggling to find its footing, telecom insiders feel that the least the government can do is ease their regulatory burden.

“The government needs to do something to help such companies survive,” said Parvez Iftikhar. “They cannot control OTT apps but they can reduce the regulatory conditions [on telecom companies] because unless that happens, the competition between the free OTT apps and the local industry is not fair.”

Of course, there are things that the government cannot control, such as the fact that Pakistani telecom companies, until recently, did not share the infrastructure for their cellular towers and each company built up its own. But tower sharing, ultimately, is just a cost-cutting measure. It does not stifle revenue growth in the manner the government’s heavy-handed approach towards telecom regulation can and does.

That said, until the regulatory framework changes, if ever, for now Jazz needs to play with what it has. And for now it had a choice to make to continue to invest in Veon, or to move away to a more lucrative platform like JazzCash to provide the same, or at least similar, financial services. It seems then that Aamir made the better choice.