Advertising has become spooky. Just imagine, how many times has it happened that you have nonchalantly Googled something – anything – a mattress, or a fridge, or a jacket, only for it to show up on your Facebook timeline with a link to shop for it online the next time you open the app on your phone? Or you sent your friend a message on WhatsApp asking for opinions regarding what place is best to get certain sports gear for instance. Next thing you know, it is right there in a sponsored post on Instagram. Perhaps the most chilling one is when you have not even put anything on your phone, and an ad for something you were just talking about with someone in person shows up.

Targeted advertising has evolved – and with its level of invasiveness, and in turn, accuracy, it holds the key to the future of marketing. Because of its eerie prevalence, one imagines that it is set to leave traditional advertising in the dust. Sure, billboards are not going anywhere for now, but how long until companies realise there are much more targeted and efficient ways to advertise their products than buying expensive airtime or print space.

In Pakistan, it would seem like there is significant time yet. Because despite the rapid expansion of targeted advertising through social media, television channels are still vying for a slice of the whopping Rs82 billion a year advertising pie, of which Rs38 billion in spent on television ads, according to estimates by Aurora magazine. And with hundreds of channels to choose from, companies have a tough time figuring out what slot of airtime they should pick to push their product to best reach their target demographic.

At the center of these decisions are television ratings, or Television Audience Measurement (TAM) numbers in industry jargon. These are those hallowed numbers that powerful media executives salivate over, and producers and hosts are willing to sacrifice an arm and a leg for. Every time an uncle sees something he does not like on television, the mantra he mutters under his breath is that the media sells out for ratings.

But television ratings themselves are a product – a currency as TAM providers like to call it. From the old days of diary entries, measuring media ratings is a complex exercise in the field of data science and analysis. At the center of this system in Pakistan is MediaLogic, and overnight ratings provider led by its founder and CEO Salman Danish. With a sample size of what they claim is a carefully selected 2,000 households, MediaLogic provides advertisers with data such as what age, gender and other demographic are watching what and at what time – allowing advertisers to optimize their buying of media.

But while MediaLogic claims to be an overnight ratings provider, they have not been free of scandal and controversy. In 2015, a back and forth spat with the Express Media Group had involved accusations of bribery, kidnapping, extortion and a plethora of unethical behaviours.

Despite all this, the company continues to hold a virtual monopoly on the TAM services business – something it claims is a good thing that encourages a uniform ‘data currency’.

The hold of MediaLogic had prompted action in the recent past by the controversial former Chief Justice of Pakistan, Mian Saqib Nisar. Since the Supreme Court delivered its decision, new TAM providers have entered the market and all ratings now go through the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA).

But MediaLogic still remains top dog in the industry, which begs the question: how exactly did Salman Danish come to wield this much power and influence? How do television ratings in Pakistan work in the first place, how has the system changed since PEMRA has become involved, and what is the future for the TAM industry? Profit takes a look.

The Nielsen rating

Sometimes, a product is so deeply influenced by a company that the product becomes known by the company’s name. And much as Coke become synonymous with cola, so did Nielsen with TAM services. The ‘Nielsen’ rating was the first of its kind television audience measurement system that used something called ‘peoplemeters’.

The people meter was a small box attached to a television set that would ask viewers to inform the television about their sex and age before they watched television to monitor their television-viewing habits. Today, it seems a primitive type of data collection. A sample of ‘Nielsen families’ would be paid a small stipend to have their television activity monitored and recorded. These families would make up a representative sample to provide advertisers with information that would allow them to most effectively place their product on television.

So, when Pakistan was undergoing its television boom in the early 2000s, it was not so strange that the Pakistan Advertisers Society (PAS) approached AC Nielsen Pakistan to help them introduce people meters to Pakistan. Much like the rest of the world, advertisers were no longer satisfied by throwing money at the television and hoping something would stick. Now they wanted to know what age, sex, and social demographic was watching which channel at what time so they could directly take their product to them.

Before this big step from the PAS, Pakistan had still been using the diary system of ratings that were provided by Gallup – an archaic system even back in the 1980s when it was first introduced in Pakistan, which involved viewers accurately recording their television watching habits on a physical diary.

But all the hopes that the PAS had vested in Nielsen Pakistan were dashed when the company refused to do in the country what it was known best for – provide Nielsen ratings. Back then, Nielsen had expressed a distrust in the market.

“I think only AC Nielsen can answer this [question as to why they refused to offer people meters in Pakistan]. Every company has its own investment priorities and its own risk profile. Pakistan offers unparalleled potential, but it also has its own pitfalls so as an investor you have to decide whether this is the right risk profile for you or not,” says Salman Danish.

After the possibility of Nielsen Pakistan taking on this task for the PAS had crashed and burned, there followed another attempt to get Kantar Media to take on the job – a distant second to Nielsen globally. But when that fell through as well, the PAS joined hands with the Pakistan Broadcasters Association (PBA) and the deal was finally swept up by Salman Danish and MediaLogic.

The sample size

After the contract was awarded to MediaLogic, they conducted an initial Establishment Survey of 3,500 homes, and selected a sample of 500 for people-meter installation and Nielsen-style ratings for the first time were available to advertisers. Today, MediaLogic has expanded to an Establishment Survey of 18,000 homes and a sample size of 2,000.

“These households are recruited as a sample of the population i.e. they need to be representative of the characteristics of the overall population. While trying not to make this too technical, I will explain the selection system,” said Salman Danish, in an interview with Profit. “This is done through a two-stage process. The first stage is called an Establishment Survey. This is a large-scale survey of the population (in our case more than 18,000 homes) from where demographics, lifestyle and TV viewership trends are documented. Results from the Establishment Survey give us indicators on the parameters of the population such as gender split, socio-economic class (SEC) breakup, TV and cable penetration in each city.”

“These also become the targets for the sample. From amongst this data, then the sample is selected to represent the same breakups that the Establishment Survey results reflected. For example, if the Establishment Survey shows that 95% of homes in Karachi have cable, then our sample should also select 95% of homes with cable access and so on,” he goes on to explain.

MediaLogic has also recently partnered with Kantar Media. And while the overall methodology of MediaLogic remains the same, Kantar has been instrumental in the larger sample size. It has also brought the latest TAM technology to Pakistan – Kantar boxes. These souped-up people-meters currently deployed in Pakistan are state of the art and the same ones used in UK and China panels. “I also believe that the client-end software offered by Kantar is much superior and advanced than the one we were using previously,” says Salman Danish.

Despite this expansion, a sample of 2,000 in a country with a population of nearly 200 million does not seem representative – and the scientific method that goes behind TAM numbers seems compromised.

Across the border in India, which has a population of more than 1.3 billion, the viewership habits of over 197 million television households accounting for 836 million TV viewing individuals is measured by the Broadcast Audience Research Council (BARC). BARC is a joint industry company founded in 2010 that is the world’s largest television audience measurement service. Its measurement system is based on 40,000 homes all across India.

The ratio of sample size to population in India is nearly four times larger than in Pakistan. But little can be done about this, since the sample size is a simple question of demand and supply. The more that advertisers are willing to invest in TAM numbers, the larger a sample there can be.

“This is totally correct and unfortunately not very well understood by people. The larger the panel, the greater the cost of research,” says Salman Danish. “However, our market, while being very large in population is not very large in terms of its market size. Therefore, clients cannot afford a very large sample. Therefore, they decided to start with a very small panel.”

“So obviously the first and most important factor that influences the market to spend more is market size. If the media market keeps growing, the panel size will also grow. The second factor is the importance given to research. Again, unfortunately in our market a lot of clients do not spend very big amounts on research and in times of financial pressures, research and advertising budgets are the first to go,” he goes on to say.

“Thirdly, I also feel that the number of international companies operating in Pakistan is an important factor. These companies are used to looking at this data and also understand the cost that is associated with TV ratings panels. Therefore they are much more willing to invest in larger panels that local clients. Of course, there are exceptions. There are some local clients who are very supportive and have been instrumental in expanding the panel.”

Salman Danish would have you believe that the relatively small sample is the result of a lack of vision on the part of advertisers. But there seems to be something more at work that has kept MediaLogic at the top of the game. AC Nielsen had not joined the TAM fray because it lacked confidence in the market back in 2001. When contacted, they told Profit that since they do not have a presence in TV audience measurement and ratings in Pakistan, they would forego commenting in this area.

However, some officials did separately say off the record that not only did they lack confidence in the market, but also had to look out for their image as an international company, since the ratings business in Pakistan was a dirty one.

The court hearings

In September 2018, a three-member bench led by former Chief Justice of Pakistan Saqib Nisar announced that TAM ratings would from then onwards come through regulatory body PEMRA. As a measure to curb malpractice in the issuance of ratings, the SC ordered ratings agencies to provide the viewership data they collect to PEMRA, which would then display the data on its website and use it to assign ratings independently.

It also issued official license forms and set a 2,000 sample size minimum for companies to operate as TAM providers. While other, smaller TAM companies had also been caught up in the new regulation, at the center of the issue was Salmand Danish and MediaLogic.

The case had gone to court after Bol TV accused MediaLogic of withholding its ratings, favouring other news channels and being in an unholy alliance with the PBA. In the courtroom, proceedings had gone in a way typical of the Justice Saqib Nisar era. The powerful Salman Danish was paraded in front of court, handed a contempt notice, threatened with the forensic audit and closure of his company, and publicly berated like a petulant child.

Justice Nisar did what Justice Nisar did best, he uncle’d and he uncle’d and then let Salman Danish go scot free. During the course of the proceedings, their lordships hammered away at MediaLogic for its monopoly, but when it came time to give a decision, PEMRA’s involvement was the only concession TAM providers had to make. In fact, the court also ruled that the PBA would no longer have anything to do with ratings, effectively given Salman Danish more power and influence over media ratings. And when Bol’s counsel argued that this would simply result in the creation of a cartel all over again, the court said the matter was settled.

Defending the idea of a monopoly in the TAM business, however, Salman Danish insisted that it was good practice to establish data currency. “This is a very interesting aspect of the TV ratings business. Globally, it is considered a best practice to have a single TV ratings data currency that all advertisers and broadcasters can agree upon. This is done by tendering this service every few years and awarding a contract to whoever comes up with the most effective measurement plan as per the specifications of the tender. The same practice is repeated after few years to ensure healthy competition and latest methodology,” he said.

“However, the Honorable Supreme Court felt that this practice should be adapted in Pakistan to allow multiple service providers and tasked PEMRA with this as a regulatory body. Medialogic became the first licensee of PEMRA fulfilling all their license requirements and is now operating under the new regulatory regime. While any new system encounters teething issues, so far our experience with PEMRA has been quite positive and we are delivering data as per the regulators specifications.”

But this was not the only time MediaLogic has had a controversial run in with the law. Back in 2015, Salman Danish had accused the Express Media Group of bribing MediaLogic employees to manipulate and get more favourable ratings for their television shows. Express responded by claiming that Danish was trying to extort Rs450 million from them and accusing the ratings provider of a wide range of illicit activities, including but not limited to kidnapping, ransom and blackmail.

The fact remains, that people meters are easy to manipulate, and a single person having so much control of the data means that there remain unanswered questions about the possibilities of wrongdoing. What happened to Bol TV was a single case of MediaLogic withholding information. What happened with Express a scandal that can be read either way.

Back in 2012, Aurora magazine, Pakistan’s leading publication dedicated to covering the advertising sector, had reported on MediaLogic and people-meters as well. The report from seven years ago says that there is “a serious trust deficit in people-meters. The bulk of the controversy is related to two issues: erratic spikes and drops in ratings which have led people to believe that certain channels may be ‘buying’ the ratings; and the delay in the delivery of data (Medialogic delivers the data with a one-day time lag) leading to the conclusion that it might be doctored.”

“Beyond those issues which people are willing to discuss on the record, there is plenty of off-the-record comment. Although no one will give exact names and facts, many say that the panel is subject to tampering. Others contend that the reason the system remains largely unregulated is because it is in the interests of the larger media buying houses and agencies (which endorse a particular channel or group of channels) to keep it that way,” it goes on to read.

The situation today remains the same. Media buying houses and channels continue to hold that data is often slow to arrive by up to three days. MediaLogic claims that the one-day lag is also only because they have to screen the data, but the company’s detractors have raised the question of what exactly they’re checking if the data is all computerised?

“The situation was crooked as it was, but ever since PEMRA has come in, it has become even shadier,” says the owner of one major media group speaking to Profit off the record. He sees a more sinister angle to it, indicating that the involvement of PEMRA could be another censorship tool. “What PEMRA says will go, what the powers that be tell PEMRA is what the ratings will be,” he says.

“Before it used to be Salman Danish himself, now it will just be Salman Danish and PEMRA. It used to be one man fudging the numbers, but now it’ll just be two or three doing with them what they please.”

“Meanwhile the advertiser will go on believing the ratings. Their people in Pakistan will tell the multinationals these numbers are legitimate and they will go on believing,” he ends.

“This is factually incorrect,” Salman Danish simply says. “There have only been a few instances in the past 12 years where data was not delivered the next day and these were only when there was a technical issue. For example, the government has at times in the past shut down cellular service in the major cities which restricts us from collecting data that day so obviously we cannot release data till we collect it. Otherwise we always deliver data next day. I don’t think there has been any such instance since 2015 when we switched to Kantar technology which has improved our data collection rate as well.”

The future

The future of TAM services is a questionable one. We started this piece with the dawn of a new kind of advertising – one targeted to every single consumer instead of targeting demographics. In such a world, one wonders how much longer television and television audiences are going to be factors.

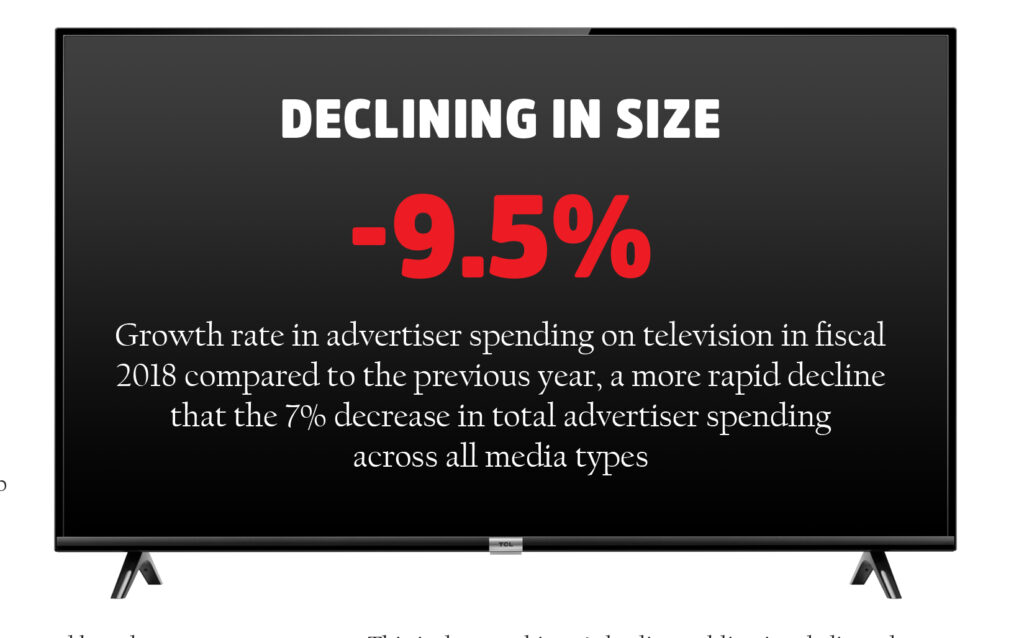

The data is already showing the trends. According to Aurora, even as total advertising spending in Pakistan fell by 7% from Rs87.7 billion in the fiscal year ending June 30, 2017 to Rs81.6 billion in fiscal 2018, the market for digital advertising grew by an astounding 46%. Even more astounding: the pace of growth in digital advertising is actually increasing: in the fiscal years 2016 through 2018, digital spending has grown by 27%, 22%, and 46% respectively.

Even within the world of television itself, some have said that the proliferation of direct-to-home (DTH) television itself could take down TAM provision in a single swoop.

“Not at all. The data DTH companies have is very different from TAM data. Nowhere in the world does DTH data become industry currency because of many factors. Firstly, DTH data is never representative of the entire population, it only represents a small premium market segment,” Salman Danish counters.

“Secondly DTH data is not individual data, it is household data which is not what advertisers require. Thirdly and perhaps most importantly it is one distribution platform data. Channel placement, bouquet formation, pricing, all determine viewership on that platform and may be very different from viewership on other distribution platforms like cable, IPTV etc. So DTH data in terms of TV ratings is never considered industry currency for ratings.”

“Having said that, TAM companies like us have to be open to collaboration with new platforms like IPTV and DTH so that our data continues to remain representative. We have to evolve and create data platforms that accept and integrate with new data streams coming from DTH and IPTV. Combining these data streams, I believe will be the key to accurate TV measurement in the future” he ends.

Clearly Salman Danish is confident in his technology and secure in the thought of his company’s future. What remains, however, is the shroud of mystery that continues to surround media ratings in Pakistan. PEMRA, while giving oversight, still is only collecting and distributing the numbers to stop MediaLogic or other TAM providers from withholding information – they have no control over the numbers coming in.

Back in the earlier mentioned Aurora story in 2012, one of the suggestions had been a joint industry committee (JIC) to regulate the system. The only problem, again, had been a lack of trust in the transparency of the numbers. Across the border, also, the BARC was a similar concept to a JIC – a joint venture of the media industry to help each other out by promoting fair competition and regulating ratings themselves. Today, the same hitch remains with such an arrangement, and now with the Supreme Court ruling that PEMRA would distribute the ratings, the chances of a JIC are slim to none.

With all the mess surrounding what should simply be computer-generated numbers and data, one wonders if Nielsen was right or not right all those years ago when they refused to get into what they saw would be murky waters.

This is not good journalism. Lots of innuendo and he said, she said, without making people. But more importantly major facts missing.

So for instance the writer does not even know that a JIC was formed for 3 years in Pakistan and it was only the SC action which made the JIC redundant. It was called BAC..Broadcasters Advertisers Council.

Not very credible this whole report.

Naming* people

[…] knowledge and tendencies. Evaluating itself to Media Financial institution, The Media Trackers, and MediaLogic, the score company claims to supply correct outcomes and better insights at a cheaper […]

[…] television viewership data and trends. Comparing itself to Media Bank, The Media Trackers, and MediaLogic, the rating agency claims to offer accurate results and greater insights at a lower […]

[…] television viewership data and trends. Comparing itself to Media Bank, The Media Trackers, and MediaLogic, the rating agency claims to offer accurate results and greater insights at a lower […]

Comments are closed.