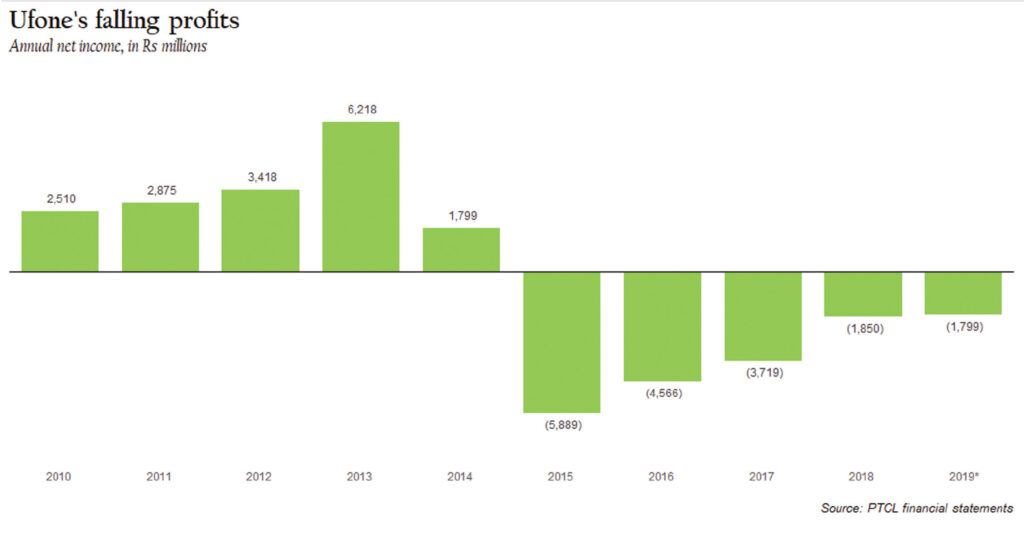

On the surface, it looks like a clear cut mistake: the state-owned Pakistan Telecommunications Company Ltd (PTCL) owns Ufone, which until just a few months ago, was the only mobile communications company in Pakistan not to own 4G spectrum, a decision that has resulted in revenue growth for the company to stall and profits to plummet into losses even as its competitors continued to see growth.

The story practically writes itself. From 1947 until 1989, PTCL was virtually the monopoly provider of communications services in the country, and until 2015 remained the largest communications company in Pakistan by revenue. With that hubris came the ingredients of what appears to be its misery: a failure of management to adapt to changing consumer demands driven by technological evolution resulting in the erstwhile state-owned giant being overshadowed by its newer, nimbler privately-owned competitors.

While there is some truth in that narrative, reality is significantly more complicated. The truth is that while PTCL has certainly fallen behind in the consumer-facing mobile telecommunications industry in Pakistan, it remains the critical backbone of the national communications infrastructure. And it is the provision of that infrastructure that remains a highly lucrative business for the company.

In other words, PTCL appears to be losing in the mobile game because it has decided to focus on playing a completely different game.

Is this the right strategy? Will PTCL really be able to survive in an era of increasing technological change, particularly as one of its competitors – China Mobile, which does business in Pakistan as Zong – is gearing up to launch 5G mobile internet?

Maybe. But it will have to be very clear about what kind of company it wants to be. And it would help to know how winners and losers in the industry have been determined in the past.

A history of Pakistan’s mobile industry

The story of Pakistan’s mobile industry begins in 1989, when the government first granted licences for mobile operators. Two companies won bids for that spectrum: Instaphone and Paktel, and both were able to launch service at almost exactly the same time in October 1990. Instaphone was a collaboration between the Swedish telecom company Millicom and the Arfeen Group (a Karachi-based trading and industrial conglomerate). And Paktel was a collaboration between the UK-based Cable & Wireless and the Hasan Group of Companies.

Both of these companies, however, operated at a time when per capita income in Pakistan was very low, and the global telecommunications industry too small to make a dent. Pakistan did not get a taste of a mass-market mobile company until Mobilink finally launched its services in 1998. Mobilink was a joint venture of Motorola and the Saif Group (owned by the politically prominent Saifullah Khan family, originally from Lakki Marwat).

The advantage Mobilink had was timing: it came right as the cost of communications equipment (both mobile handsets as well as the infrastructure for the cellular towers) was beginning to drop enough to become a more mass-market product and Mobilink had the good sense to come in with GSM (Global System for Mobile Communications), the standard beginning to take over Europe and what would soon become the global standard for communications.

In 2000, Orascom Holdings of Egypt bought a controlling stake in Mobilink and began investing heavily in building the company into a truly national carrier rather than simply one that focused on the major cities. Mobilink consistently had a greater than 50% market share during this period in Pakistan’s telecom history, both in terms of revenue as well as number of subscribers.

In 2001, more than a decade after the emergence of a Pakistani mobile industry, PTCL decided to enter the fray with Ufone and quickly began to take market share. By 2006, within five years of its launch, Ufone had gained a 21.7% share in terms of the number of subscribers and 17.9% in terms of revenue. In retrospect, however, that may have been Ufone’s high-water mark.

The pioneers in the industry – Paktel and Instaphone – continued to die a very painful death. Instaphone was bleeding itself into the grave because it continued to stick with Digital-AMPS technology even as GSM had become the dominant technology even in North America, the birthplace of AMPS. Paktel tried to save itself by converting to GSM in 2004, but it was too little too late.

Meanwhile, two new players had entered the industry. Telenor, the Norwegian telecom giant, launched its services in Pakistan in March 2005. And then came Warid, a new company that had the backing of the Abu Dhabi Group (owned by members of Abu Dhabi’s ruling Nahyan family), launched its services in Pakistan in June 2005.

And the race was on. And Ufone did not know what hit it.

By mid-2008, Telenor had caught up with Ufone in terms of the number of subscribers. Perhaps even more impressive for Telenor was the fact that they did so while having a higher average revenue per user (ARPU) than Ufone. The year 2008 was when Telenor became the second-largest mobile operator in Pakistan and Ufone never regained that title since then.

The year 2008 was also the year China Mobile officially launched the Zong brand in Pakistan. The company had bought a dominant 88.9% stake in Paktel a year earlier, in January 2007, for $284 million. China Mobile increased its stake to 100% by May of that year.

And thus began the era of the five mobile operators in Pakistan that continued for almost a full decade. Ufone was comfortably middle of the pack for almost the entire time.

The beginning of Ufone’s struggles

Even while it was allowing new companies to gain market share, Ufone’s financial position remained relatively stable, and it even gained some share of wallet. The peak for the company came in 2011, when Ufone accounted for 21.9% of the industry’s revenues. In hindsight, that was probably as good as it was going to get.

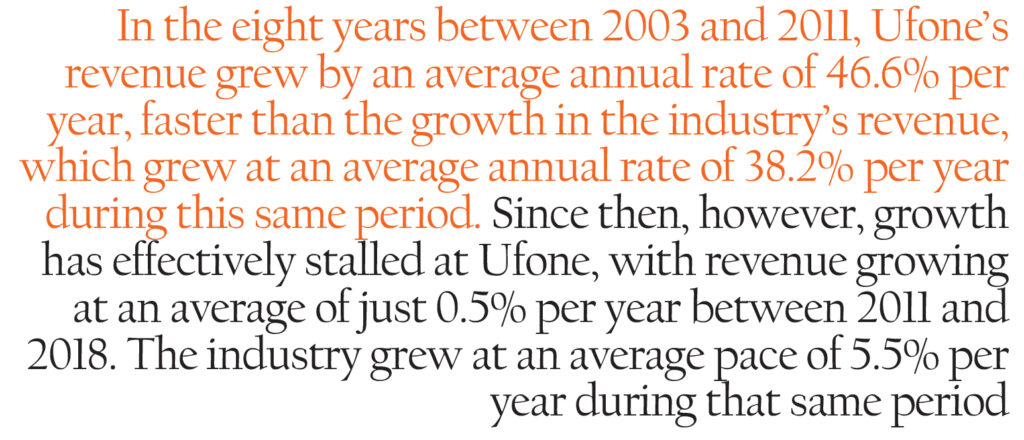

In the eight years between 2003 and 2011, Ufone’s revenue grew by an average annual rate of 46.6% per year, from Rs2.7 billion in 2003 to Rs60.5 billion in 2011. This was significantly faster than the already very rapid growth in the industry’s revenue, which grew at an average annual rate of 38.2% per year during this same period, from Rs19.8 billion in 2003 to Rs263 billion in 2011.

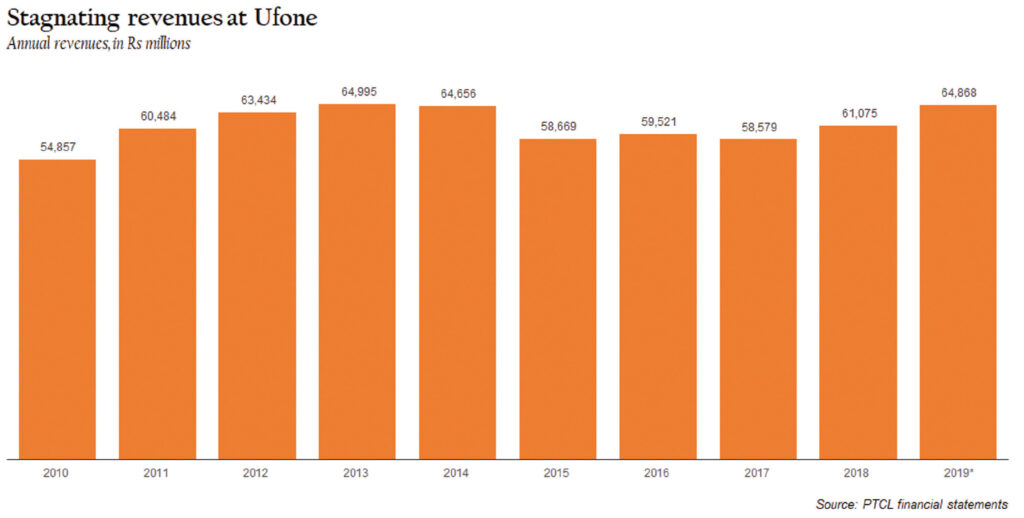

Since then, however, growth has effectively stalled at Ufone, with revenue growing at an average of just 0.5% per year between 2011 and 2018. The industry grew at an average pace of 5.5% per year during that same period. Ufone’s market share was down to 15.6% by the end of 2018.

So what happened? Well, the rules of the game changed, and on the surface it looked like two players were caught off guard: Warid, and Ufone. Warid was ultimately bought out by Mobilink (since renamed Jazz). Ufone continues to struggle on.

Was it really that bad? In hindsight, it appears so. But if you look at their decision-making at the time, Ufone was not necessarily making mistakes.

The spectrum auctions

In April 2014, years after having first broached the discussion of auctioning 3G and 4G spectrum in Pakistan, the government finally decided to conduct the auction that would allow mobile telecommunications to evolve to the next logical stage in the country.

It was an auction that appears to have been designed to winnow the field of mobile operators in Pakistan. Five national operators was just too many. Even in the United States, four national operators feels like too many, let alone five in a small market like Pakistan.

So the government decided it would only auction off four 3G licences and two 4G licences. At the time, most Pakistanis still owned feature phones, and the few people who owned smartphones had to make do with 2G Edge connections, which could only charitably be described as a mobile internet connection. So even a move to 3G would have felt like a big move for most consumers.

In other words, it would be completely rational for the mobile companies to assume that getting 3G spectrum would be enough and that there was no need to bid an absurdly high amount for 4G spectrum, particularly when the base price for 3G spectrum itself was set at $295 million for each licence. Everyone knew that Warid – as the smallest and least financially stable of the mobile operators by subscribers – would not have enough money to bid and would likely not even participate in the auction, meaning the other four were guaranteed a 3G licence at the base price.

Unfortunately for the other three, Zong had other ideas. Its parent company, China Mobile, was keen to change the game for itself in the Pakistani market. By 2014, Zong had grown to become the third-largest mobile operator by subscribers, but it was seen as the low-cost option and had an ARPU significantly lower than all of its competitors. Zong was gaining market share, but at the expense of profitability.

The company saw data as its potential game changer and effectively decided to act like a poker player going all in on its last hand at the game. Zong had the highest bid for the 3G spectrum at $307 million, which rendered it eligible to get a 4G licence at the base price of $210 million. (It was not possible for a company to bid for just 4G spectrum without also seeking a 3G spectrum licence.)

China Mobile spent $517 million (then Rs52 billion) getting those licences, even as all of its competitors chose to get 3G licences at barely above the base price (Telenor and Ufone actually bid just the base price).

And soon after the auction was over came another surprise: Warid had not skipped the auction for no reason. When it had first bought its spectrum from the government in 2004, it had requested a “technology neutral” licence, meaning it could launch 3G and 4G mobile internet on its existing spectrum, which it announced it would promptly begin investing in.

So at the end of the auction, there would be two companies that had 4G spectrum, and three that had 3G spectrum. What happened next should have been predictable, but nonetheless appears to have caught the industry off-guard.

Between 2012 and 2015, the mobile industry saw its revenues increase by Rs18.5 billion. During that same period, however, Zong’s revenues grew from 20.4 billion to Rs47.8 billion, an increase of Rs27.4 billion. Yes, you are reading that correctly: Zong’s revenues grew by more than the entire industry combined, meaning Zong gained market share at the actual expense of its rivals’ revenues.

Needless to say, that caught the attention of just about everyone in the industry. In 2016, when the government put more 4G spectrum on auction, both Telenor and Mobilink leapt at the opportunity to buy some for themselves, in order to ensure that they would be able to offer 4G services to their consumers and stop losing market share to Zong.

Ufone, however, was not among those companies that spent any money on 4G spectrum, which is surprising because of the Rs8.9 billion in revenue that Zong took from its competitors in 2015, Rs6.0 billion came from Ufone, with much more minor declines from Mobilink and Telenor.

Meanwhile, Warid’s play for 4G was floundering since the company simply did not have enough cash to build out its infrastructure. In November 2015, Mobilink bought out Warid and, in January 2017, renamed the combined company Jazz.

At this point (mid-2016 or so), Ufone’s problems appeared to be getting worse. Because the largest mobile operator in Pakistan had just gotten larger, and all three of its only competitors left offered 4G services. Would Ufone end up like Instaphone and Paktel? For a while, it certainly looked like it.

The ‘strategic alternatives’ rumours

According to sources familiar with the deliberations at PTCL’s senior management, soon after the Warid-Mobilink merger was complete – and having 4G services became table stakes for being a mobile operator in Pakistan – PTCL seriously considered exiting the mobile operator game altogether.

Sources tell Profit that there were at least initial discussions about possibly selling a stake in Ufone. It is unclear how advanced the talks were before ultimately falling through. But the mere fact that such deliberations occurred suggests that PTCL management were clearly aware of just how much trouble their mobile subsidiary was in during 2016.

The rumours grew so persistent that in September 2016, Etisalat, the UAE-based telecom company that owns a management stake in PTCL, put out an official statement denying the rumours. “PTCL on confirmation from Etisalat would like to categorically state that no discussions regarding sale of Etisalat’s stake in PTCL and its subsidiary Ufone to any company have taken place,” the company said in a statement released to the press.

This was about six months after Daniel Ritz had been brought onboard as the first non-Pakistani CEO of PTCL. Ritz, a Swiss citizen, joined PTCL in March 2016, after having worked in Dubai for four years as the Chief Strategy and M&A Officer for Etisalat. Needless to say, having an M&A specialist take over as the CEO of a company did not help quash rumours about possible M&A activity involving that company’s struggling subsidiary.

In an interview Profit conducted with Ritz in February 2019, shortly before he was ousted, the then-CEO tried to downplay the troubles that Ufone was in. “Ufone has increased its customer base, grown revenues and won back market share in every single quarter. It’s a focus of the management and employees on growth. They have started believing in it again, and have become more aggressive in customer acquisition. And at the end of the day, Ufone has a good network. It doesn’t have 4G, but if you look at the last quality survey done by PTA on voice, Ufone scored very high. They might have fewer customers than others, but less customers also mean better quality on your network.”

But besides the unconvincing statements that Ufone was somehow thriving, Ritz made an interesting and important point: that unlike all of its other competitors, PTCL is not solely reliant on offering 4G data services to consumers to profit from the growth of mobile internet usage in Pakistan.

The infrastructure behind 4G

Let us say you are sitting in Islamabad and want to do a WhatsApp video call with your friend who is currently in Karachi. Your smartphone will transmit the 4G signal to the nearest cell-tower from which the signal ultimately needs to pass through WhatsApp’s servers before it is routed back to your friend’s phone through the 4G cell-tower closest to them.

In order for that to happen, the signal is not transmitted wirelessly across the whole world. It is transmitted through fiber optic cables, a network of which spans all of PakiPakistan, the globe.

“PTCL is the carrier of carriers,” said Ritz. “In a way, the rapid data volume growth of the mobile operators is a blessing for PTCL, because these operators need a lot of capacity for data traffic. The most efficient way to carry this traffic is fiber, and PTCL has the largest fiber network in the entire country. So, while these mobile operators are competitors for Ufone, they are at the same time a great opportunity for PTCL.”

“The IRU [indefeasible right of use] contract with Zong was the first of its kind, and since then we have done more of the same. We have also signed a deal with Telenor in 2018. And there is more to come,” said Ritz.

In other words, even if Ufone did not exist, PTCL has a business that would take advantage of the fact that more Pakistanis are using data: instead of selling data services directly to you the consumer, they can sell data infrastructure services to Telenor, which in turn can sell them to you.

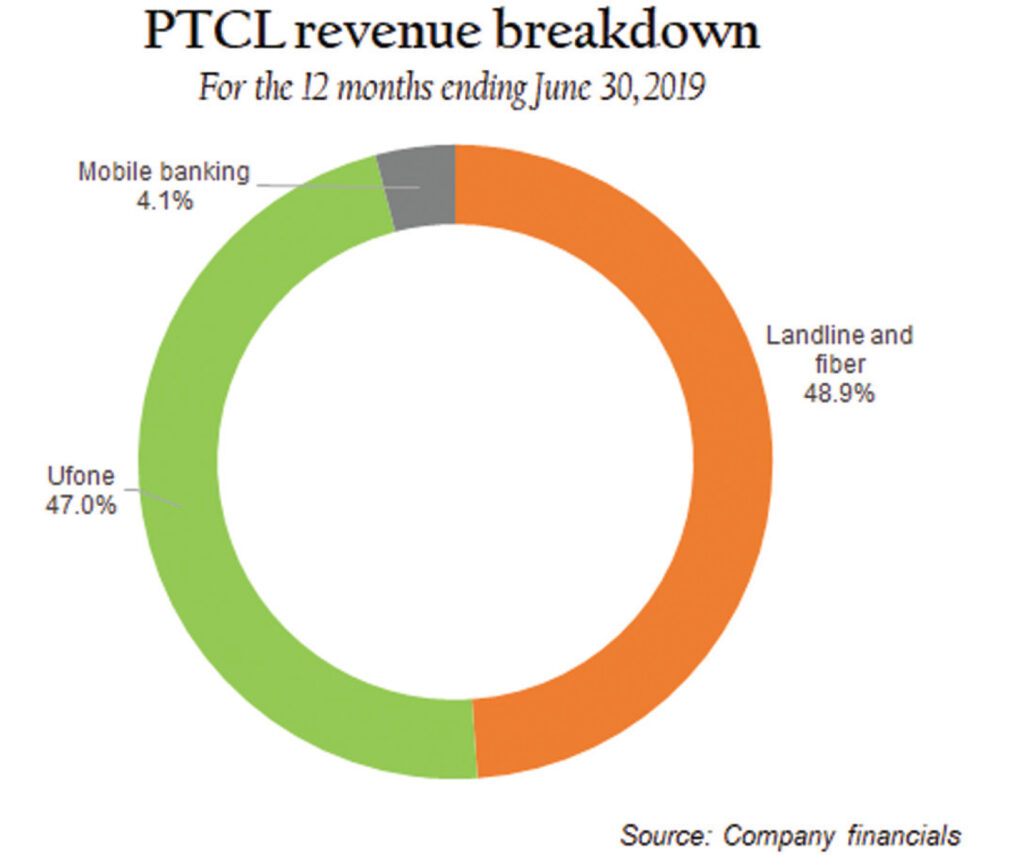

From the PTCL management’s perspective, the question then is this: you have a limited amount of cash flow generated by operations of the company, which are available for capital expenditures. Which business would you put them in? According to Profit’s analysis of PTCL’s financial statements, the core infrastructure business is yielding a 16.3% return on equity, while the mobile operator business currently has a negative return on equity: -5.7% for the 12 months ending June 30, 2019.

The solution is obvious: invest in the business that has a higher return, which in this case is the infrastructure business.

Ufone is still a headache

The problem, of course, is that just because it makes more sense for PTCL to invest in its core operations does not mean that Ufone ceases to exist. PTCL has invested tens of billions of rupees in that business and cannot afford to just let it wither on the vine.

In such circumstances, usually selling an underperforming business is the optimal option. It may not make sense for an integrated telecom operator like PTCL to invest in its mobile arm, but a company that competes only in the mobile sector – or does not have an infrastructure business – would have more use for Ufone’s assets.

Of course, based on information from Profit’s sources, that option has already been explored and went nowhere. Which means that PTCL is stuck with Ufone, whether they want it or not, and that, in turn, means that the company needs to invest in its 4G infrastructure.

Ritz admitted as much in his interview with Profit. “At some stage Ufone will require 4G spectrum to remain competitive. If, when and how that spectrum will be made available is for PTA and the government to decide,” he said.

This interview was conducted just a few days before it was noticed in February 2019 that Ufone customers in Islamabad and Rawalpindi were already able to use 4G LTE services. In a statement to ProPakistani, Ufone officials claimed that the company has all regulatory approvals needed to launch 4G LTE services in Pakistan, albeit on existing spectrum.

The hunger for 4G services in Ufone’s existing customers appears to have been pent up for quite some time. Between February and June of 2019, Ufone has managed to convert 1.9 million of its 22.6 million customers (about 8.3% of the total) to 4G, and perhaps not a moment too soon. By the end of fiscal year 2020, 4G users in Pakistan will outnumber 3G users for the first time.

It is still unclear how much PTCL is willing to invest in Ufone’s 4G rollout, which most accounts suggest is still not available in most of the country. And there is also the matter of PTCL – still majority-owned by the federal government – appearing to get the special favour of being able to roll out 4G services without paying the $200 million or more in licence fees that all of its competitors have paid.

For now, however, PTCL appears to have realised its earlier mistake: the Pakistani consumer is no longer willing to make do without 4G internet on their smartphones. And so long as PTCL owns Ufone, it will have to cater to those consumers, even if the infrastructure business is more profitable.

With additional reporting by Syeda Masooma

greatly explained. Indeed it was getting hard to stick with ufone with no 4G service available. Only the supercard service has held me back and i’m sure supercard has done a big favour on ufone in terms of revenue and holding back its customers from going to other networks.

No bashing of PTI Govt in this article? Im surprised!

By mid-2008, Telenor had caught up with Ufone in terms of the number of subscribers. >>>>>>

First: the blunder here was made by the then very weak commercial management team at ufone. A very young CMO and a very arrogant sales head. The decision was to expand the network in urban areas of Pakistan rather that horizontally expanding in rural areas like Telenor and Mobilnk did at that time. Even today, Ufone has just as many towers as Telenor, but the coverage is far less. This was in my opinion the first blow to Ufone and its return on assets.

Second: In order to catch up with this mistake, Ufone then started to over charge their customers through various VAS and became notorious for hidden charges.

These two combined brought Ufone synergies for disaster…

Third: Later in 3G era, Ufone opted for smaller frequency of 3G and soon started to have capacity issues also.

Fourth: The management installed by Etisalat in 2016, (again a very weak commercial team – in fact the sales head from 2008 was rehired), instead of riding the tide of 3G, decided to curtail the data usage of Ufone’s customers.

Fifth: The only saving grace of Ufone – the fun brand image of Ufone was also killed.

Sixth: The same management team opted not to bud for 4G license thinking that Pakistan is not ready for 4G. And that is the period when Zong went all guns blazing to steal all the growth in data market.

Seventh: When Etisalat woke up after this storm, they hired a 70+ years old CEO whose last run as the CEO of mobilink was quite disastrous including a failed warid acquisition bid and a couple of failed youth brand offers. Interestingly he is keeping rest of the team same…

In my opinion, taking measured steps vis a vis wireless Tech upgrade and being half a step behind to manage capex efficiency and to achieve full blown monetization before rushing for glamour & glitter of upgrade is the best strategy in shareholders value creation and a high ROI. However, a Telco must not delay generational upgrade as much to lose users’ engagement & experience which is important for keeping its value share higher and rising.

Zong is building its own fiber network in preparation for 5G and in order to break PTCL’s monopoly. 5G will require more towers and they will all have to be connected to fiber. 5G is the future of last mile connectivity so PTCL better do something to preserve its monopoly on fiber. Otherwise they are toast.

@Farooq Trimzi, very well written. I have been following your writings since I came across your articles in Dawn Sunday Magazine a couple of years ago.

@safwan. I am in the same boat as you. Ufone Super Card is the only thing making me stick to Ufone. Otherwise, Ufone has coverage problems in Karachi, the megacity of Pakistan, much less the rural areas.

@Another Anonymous

> The only saving grace of Ufone – the fun brand image of Ufone was also killed.

Is this why we no longer see brilliant Ufone ads from Jawad Bashir and his team?

Not only Ufone failed to be flag bearer of 4G, it has lost the last mile of G-Pon which is conquered for Zong Fiber+ in Karachi providing fiber the FTTH in urban Karachi area. PTCL left behind in G-Pon FTTH in most Karachi, and Nayatel, StormFiber, and many others are way ahead of PTCL in FTTH. PTCL Dhobi Gath broadband with black wire provides internet unlimited to naïve industry, home, business.

At least the G-Pon flag should be raised with full swing of launch of Broad Band Swing.

Regards

Comments are closed.