Business publications have a natural bias: we tend to be pro-capitalism, pro-free markets, and pro-entrepreneurship. What we at Profit try to do is not be pro-business. Being pro-free markets, and pro-business can be quite different. We recognise, perhaps more than most, that Pakistani business consists largely of rent-seeking industrial aristocrats who inherited their fortunes and are globally uncompetitive. We have no intention of defending the worst of their practices.

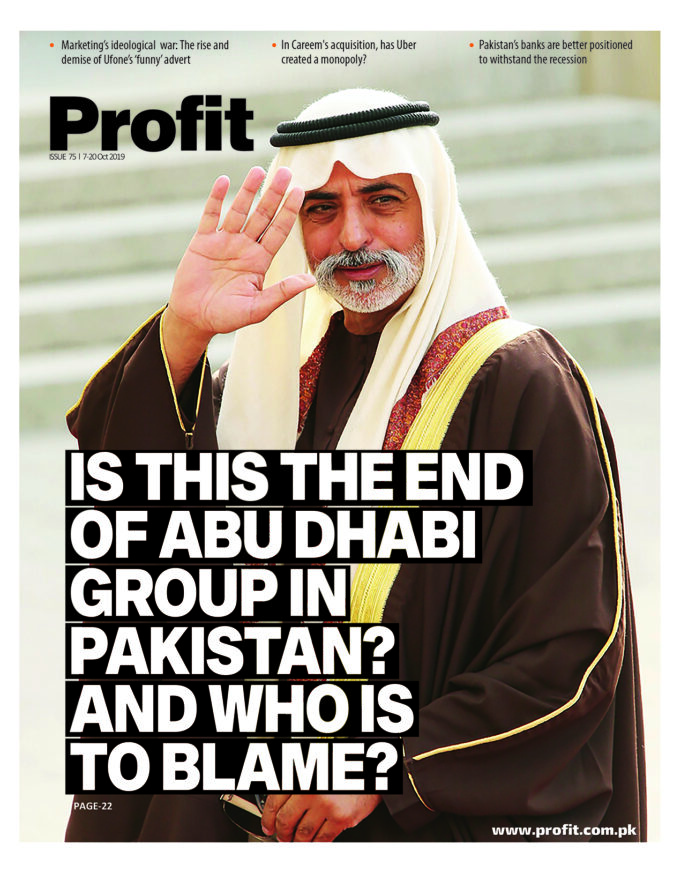

Consider the Abu Dhabi Group, whose far from ideal business practices we have taken on in this issue’s cover story. When one of the group’s many businesses plateaus, scrapes by or straight-up tanks, it is not just the group’s money that is whisked away, it also affects the lives of the many employees and sub-contractors working there. And also the consumers and customers of those businesses. And, most importantly, the smaller shareholders. Consider Wateen Telecom, whose enthusiastic IPO was followed by the same unsure attitude that has become the group’s hallmark, resulting in the stock losing around 70 percent of its value in a matter of months.

Consider also the acquisition of Careem by Uber, on which we have a story in this issue. Whereas the deal has been hailed by most and seen as an inspiring success story for a startup whose founders included a Pakistani, we at Profit have some reservations. We fear that the monopoly of sorts thus created is going to be bad for most stakeholders. And we wish for the Competition Commission of Pakistan, yes, the same CCP which, in its different avatars the world over, is the bane of Big Business, to take a good look at the structure of the industry now and see whether the magic of the free market is still unfettered.

There are, however, some instances where businesses in Pakistan really are treated unfairly, regardless of one’s position on Big Business. The National Accountability Bureau’s treatment of the Engro Corporation, its executives and now its major shareholders, we believe, is one such instance.

In an issue last month, we reported on how former Engro Elengy CEO Imranul Haque was imprisoned without charges – a violation of his constitutional rights – in an effort to build up a case on what appear on the surface to be no real charges against former Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi. And now comes the news that Engro’s chairman and largest individual shareholder Hussain Dawood has been summoned for questioning by NAB.

The inability of NAB to build up a case and charge any of these individuals is tantamount to harassment. What is worse is that it is harassment of a business – and individual executives and investors – that have been law-abiding to a fault. When the government has reneged on its contractual obligations to them, rather than bribing their way to a solution, they have politely pleaded their case before government officials and waited for the government to see reason.

Engro is the kind of business Pakistan wants and needs: a large, well-capitalised organisation that recruits talented individuals, pays them well, and gives them autonomy and money to help solve some of Pakistan’s biggest economic challenges. The liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal that Engro set up, for instance, is one of two terminals that together help fuel nearly 25% of Pakistan’s electricity supply.

Bear in mind, we have nothing against accountability. But the sheer manner in which the exercise is being carried out reeks of a Gestapo-like attitude. Businessmen are virtually hauled away from their offices, with the news being leaked to the media almost immediately. These leaks don’t have any details about whether it was initial, exploratory questioning following a tip-off, an actual investigation or proceedings following an investigation that yielded ‘smoking gun’ evidence.

If the government’s misguided “accountability drive” (which is really just political revenge fantasy on the part of the ruling party) cannot even spare the best from within the business community, who is safe? Who will feel confident investing in the country when the government not only reneges on its promises but actually has the gall to harass and imprison people who had the temerity to do business with it.

The pile of cash that Hussain Dawood was sitting on, which had led many, including Profit, to speculate where he was going to invest it, isn’t going to be utilised in Pakistan after all. Seeing the investment climate – and the treatment meted out to investors by the state – he has apparently decided to look for investment avenues abroad. He has already gotten a paid membership of the World Economic Forum – the only Pakistani to do so. Rather than making the country attractive enough for foreign direct investment, we seem to be driving out local businessmen.