It is the worst recession that Pakistan has experienced since the 1971 war, according to some measures, and one would typically expect the banking sector to be badly affected. But while non-performing loans are increasing at the banks, the 2018-19 recession appears to have had a tamer impact on Pakistan’s banking sector than the relatively milder 2008-09 recession.

Non-performing loans for the banking sector jumped by 12.2% during the first half of calendar 2019, up to Rs697 billion from Rs624 billion at the end of 2018. This marks an increase in the infection ratio of the banking sector’s loan portfolio, up from 8.0% to 8.8%, according to research by AKD Securities, an investment bank.

“Recent macroeconomic and sectoral trends do indicate rising credit risks that can pierce into banking sector profitability over the coming quarters. However it could be on a lower scale than in previous down cycle where NPLs soared at a three-year CAGR [compound annualised growth rate] of 27.7% between 2008 and 2010, translating into cost of provisioning of 1.5-2.0% [of assets],” wrote Hamza Kamal, a research analyst at AKD Securities, in a note issued to clients on September 27, 2019.

The infection ratio measures the proportion of a bank’s loan portfolio that has been classified as non-performing, meaning the bank realistically no longer expects those loans to be paid back. This does not necessarily mean that the bank has stopped trying to get repaid for those loans, just that it recognises that the probability of being repaid is very low.

The relatively mild nature of the loan losses at the banks is likely the result of a much more conservative lending culture at Pakistani banks than in the previous economic boom.

Prior to the 2008 recession, Pakistani banks had been taking significant risks with their balance sheet in virtually all areas. On the corporate lending side, banks were lending to large companies for big, audacious industrial projects that, if poorly timed, can result in significant losses. And banks had significantly larger small business and consumer lending portfolios, which tend to see higher default rates during economic slowdowns.

And that does not even include the fact that, prior to 2008, banks were very actively using deposits to invest directly into the stock market, an activity that has been severely curtailed by regulations issued by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

As of December 31, 2007, banks in Pakistan had deployed 9.1% of their investible assets into consumer lending, and 2.3% in stocks, according to data from the State Bank. Investible assets are defined as the financial (non-physical) assets of the banks.

And that number for stocks likely underestimates the extent to which banks were actually investing in the stock market. Sources familiar with the matter tell Profit that banks had a habit of having large proprietary trading books for stocks that they would reduce to much smaller amounts by selling off their shares just before the close of a quarter so that the regulators at the SBP would not catch wind of how much they were investing.

After the crisis, banks have become significantly more conservative in their lending practices, scaling back on consumer lending and cutting corporate lending to only the most plain-vanilla working capital financing loans (loans which finance a business’ running cash needs rather than financing expansion plans). The bulk of bank lending is now to the government or state-owned enterprises.

Data from the SBP shows that consumer lending now accounts for only 3.4% of the banking sector’s investible assets, while investments in the stock market are down to 1.8% of investible assets.

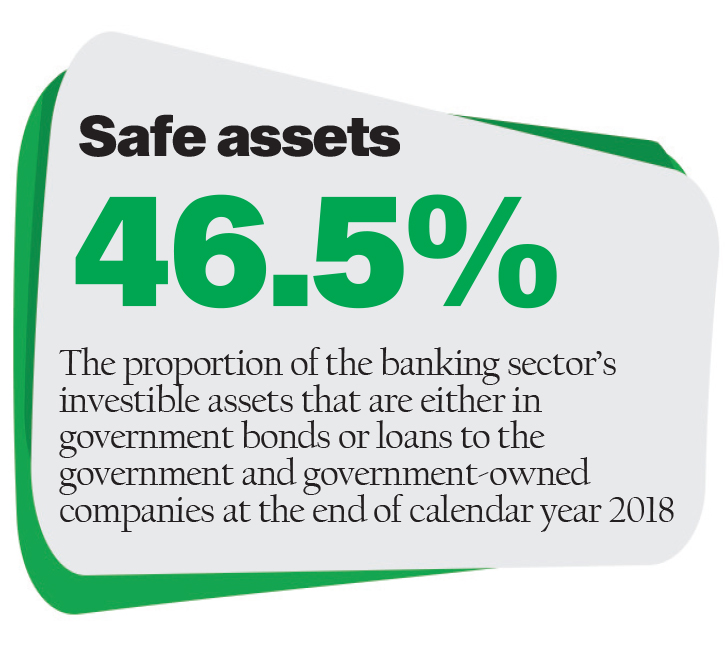

Meanwhile, the banks’ investments in government bonds, as well as loans to the government and government-owned companies, accounted for 46.5% of investible assets at the end of 2018, compared to 23.7% at the end of 2007.

Analysts generally agree that the banking sector is taking less risk than it did prior to the previous recession. “Our moderate expectation [for bank loan losses] is on the back of, 1) diversified exposure mix (share of top three sectors that occupied ~50% of total financing in 2007, now occupies one-third of overall loans), and 2) higher exposure to government-guaranteed financing (power sector loans’ share in Jul’19: 8.6% vs. 3.0% in Dec’07),” wrote Hamza Kamal, the analyst at AKD Securities.

Indeed, the banks have become so conservative in their lending practices that loan losses on their consumer lending portfolio declined during the recession. In the first six months of 2019, he banking sector’s non-performing consumer loans declined by 6.3%, the only sector to witness such a decline as every other sector saw an increase in default rates.

This is in part due to the fact that the banks appear to be getting somewhat better at consumer lending and are only lending to relatively lower-risk borrowers.

Among the sectors that have suffered the worst increases in defaults are the power generation and electronics sectors, both of which saw an increase in defaults of over 20% during the first half of calendar year 2019. Even worse, however, was agriculture, where defaults have gone up by 28.5% during the same period, according to an analysis by AKD Securities.

The relative stability of the banks suggests that even as interest rates rise, banks are unlikely to see a significant erosion in their profitability, and are likely to be well-positioned to take advantage of any economic recovery.

Banks in Pakistan are very fat and risk averse. The SBP has totally failed to create competition in this sector or motivate banks to lend to the private sector. It allows them to mint money by borrowing interest free from current account holders and lending risk free to the government. The islamic psyche ensures that savers don’t seek out high interest rate savings accounts and instead prefer to keep their money in zero interest current accounts.

Banks make so much money that they don’t even bother to invest in digitization. They have effectively lobbied the central bank into putting up barriers to fintech firms. The SBP has also not created a common money transfer system in the country. Other countries have taken the lead by creating a unified and cheap countrywide money transfer system with open APIs for developers to use.

Comments are closed.