It is a truth universally acknowledged, that Pakistan’s first free trade agreement (FTA) with China was a bit of a dud. Signed in 2006 with much fanfare, and beginning operations in 2007, Phase 1 of the FTA did little to improve Pakistani exports to China, and only worsened our trade deficit with our neighbour.

So Pakistan went back to the drawing board, with somewhere between 11 reported meetings of negotiations over seven years with the Chinese. The result is Phase 2 of the China Pakistan Free Trade Agreement, which was finalized in 2019, and implemented on January 1, 2020. This new phase is set to last until 2024.

Not everyone is happy: just this week, there were grumbles from the Federation of Pakistan Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FPCCI) on whether Pakistan could fully take advantage of the FTA, considering how useless and poor Pakistan’s exports are. Instead of signing an FTA, the the FPCCI called upon the government to “urgently develop a robust and holistic industrial policy that would lead to massive industrialisation.”

Try out our new feature: Listen to the full article below

Considering that the last time Pakistan had any semblance of a formal industrialization policy was around 60 years ago, the FPCCI plea is just a little too late. But it is a valid point to raise – what is even the point of an FTA with China? Are Pakistani exporters actually going to benefit, or is this another poorly thought out scheme designed to look good in the news, and little else?

Fortunately, there’s a study out there to answer this: the “China Pakistan Free Trade Agreement Phase II – A Preliminary Analysis”. Written by LUMS economists Nazish Afraz and Nadia Mukhtar, the report was commissioned by the Pakistani Business Council (PBC), and the Consortium for Development Policy Research. (The PBC is a lobbying group for big business in Pakistan and was established in 2005. It features 82 Pakistani conglomerates and multinationals.) Their research indicates that, for now, the results look a little promising, albeit with a few caveats.

But first, what happened in Phase 1?

A little context: Pakistan’s global exports have never been the healthiest. According to the Economic Complexity Index, Pakistan ranks 94th in terms of the complexity of products it exports. Similarly, on the Global Competitiveness Index, Pakistan ranks 107th out of 140 countries. And despite Pakistan’s global exports increasing by 47% between 2005 and 2018, imports have gone up by 140% in the same period.

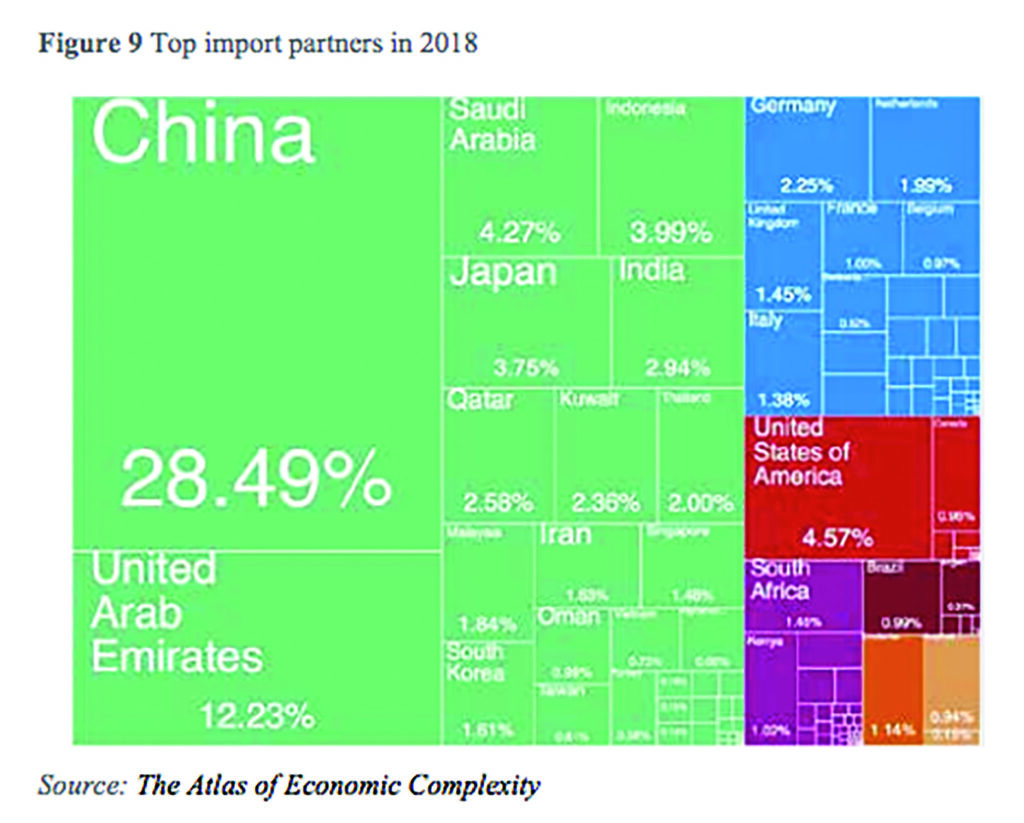

On top of these great global figures, Pakistan’s trade with China has always been asymmetric. Consider: only 7% of Pakistani exports went to China – most went to Europe and the United States. On the flip side, China took up 28.5% of Pakistan imports – by far the largest trading partner.

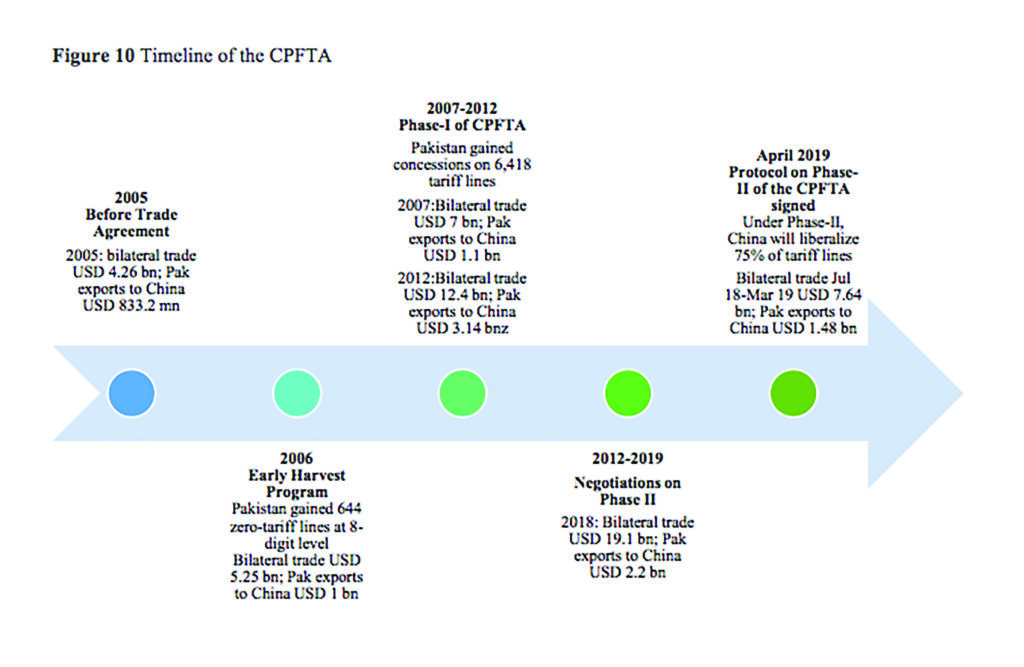

The original FTA was meant to address, and also foresee, these sorts of problems. The first phase spanned between 2007 and 2012, and involved the elimination of tariffs on 7,500 tariff lines.

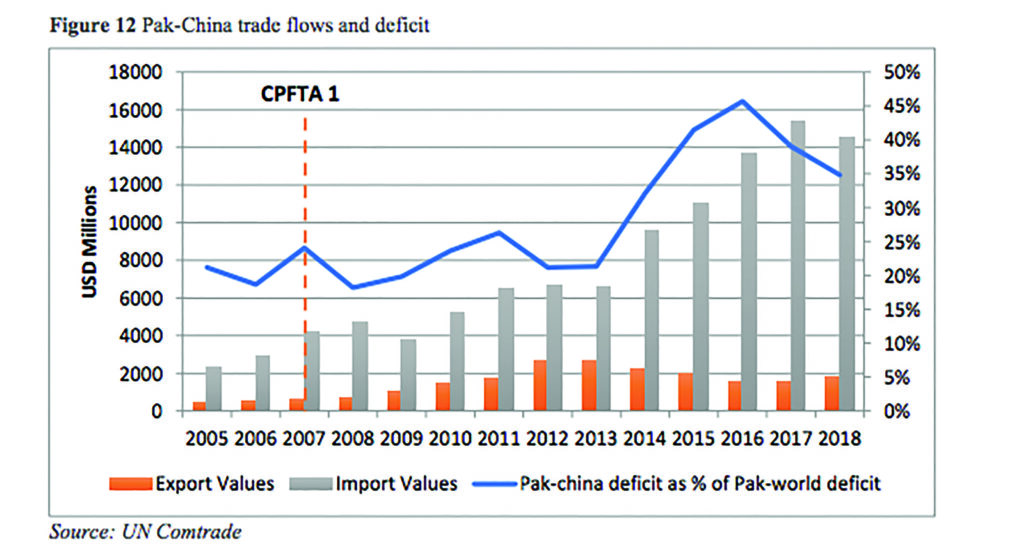

The original aim was to speed up bilateral trade. As per the report’s analysis: “bilateral trade flourished, growing by 242% between 2007 and 2018—nearly six times faster than the growth of Pakistan’s trade with the rest of the world in the same period.” Total trade with China since the signing of the FTA also shot up, to $16.4 billion in 2018.

Phase 1 of the FTA changed the nature of the kind of exports that were sent to China. Prior to 2007, Pakistan was exporting mostly ores, slag and ash; raw hides and leather; machinery and mechanical appliances; oil seeds; and copper to China. But after the FTA, Pakistan began to send more cotton, plastics, organic chemicals, gums and resins. Cotton in particular emerged as a winner, with “exports to China have grown from $271 million to $873 million between 2015-2018.”, according to the report.

However – and it is a big ‘however’ – this FTA benefited China significantly more than it did Pakistan. Between 2014 and 2018, Pakistani exports to China declined 7% annually, while imports from China rose 12% annually. Another way of looking at it: Pakistan’s trade deficit with China represented 25% of Pakistan’s total trade deficit in 2007. By 2018, this had shot up to 38%, or around $13 billion.

Why did this happen? Well, Pakistan offered much better concessions to Chinese exports than China did to Pakistani exports. This was something China exploited, as evidenced by the the difference between the utilization rate of preferential tariff lines by China (57%) and Pakistan (5%).

According to the report: “This led to the domestic market being flooded by China’s exports of finished products comprising clothing and shoes, medical and surgical items, and fans and rubber tires, thereby curtailing local production in Pakistan and preventing local producers from achieving economies of scale in the face of low profitability.”

Most of the duty-free access to China was given to low value products, like cotton bedsheets, minerals such as chromium and copper, and cotton yarn (the latter made up 40% of Pakistan’s total exports to China in 2017). These industries are a small part of the Pakistani economy, but are important raw material providers to China’s higher value export industries: readymade garments, electronics, etc.

But China offered little to no concessions on what are actually Pakistan’s top exports, like rice, frozen fish, crab, leather hides, knitted cotton apparel (the latter made up just 2% of Pakistan’s exports to China in 2017). In hindsight, the first China-Pakistan FTA should have been a warning about the kind of unbalanced, exploitative economic arrangements China has a habit of pursuing.

These kinds of discrepancies, real or perceived, also irked business groups in Pakistan. The report claims business groups “believed that Pakistan had negotiated poorly, both in terms of getting access for the products for which it was better placed to export to China, and also in terms of granting access to Chinese goods that were perceived to have inundated the Pakistani market, contributing to premature deindustrialization.”

But the biggest impediment in gaining any benefits from the FTA, was in fact something out of the FTA’s control. In 2010, China signed the ASEAN-China FTA (ACFTA). Pakistan’s comparative advantage was practically destroyed, as China offered infinitely better tariffs to ASEAN members and also to one of Pakistan’s biggest competitors, Bangladesh. In fact, the ACFTA has been estimated to have led to a whopping loss of 80% of Pakistani export volume to China.

Which obviously leads to the question: what is the point of an FTA between two countries (no matter how poorly thought out), if any gains are to be eradicated due to a completely unrelated FTA?

The new and improved FTA

Phase 2 of the FTA (to be called FTA2) was negotiated with these problems in mind. According to the report’s preliminary analysis, the outlook is hopeful, and the tariff structure has definitely improved.

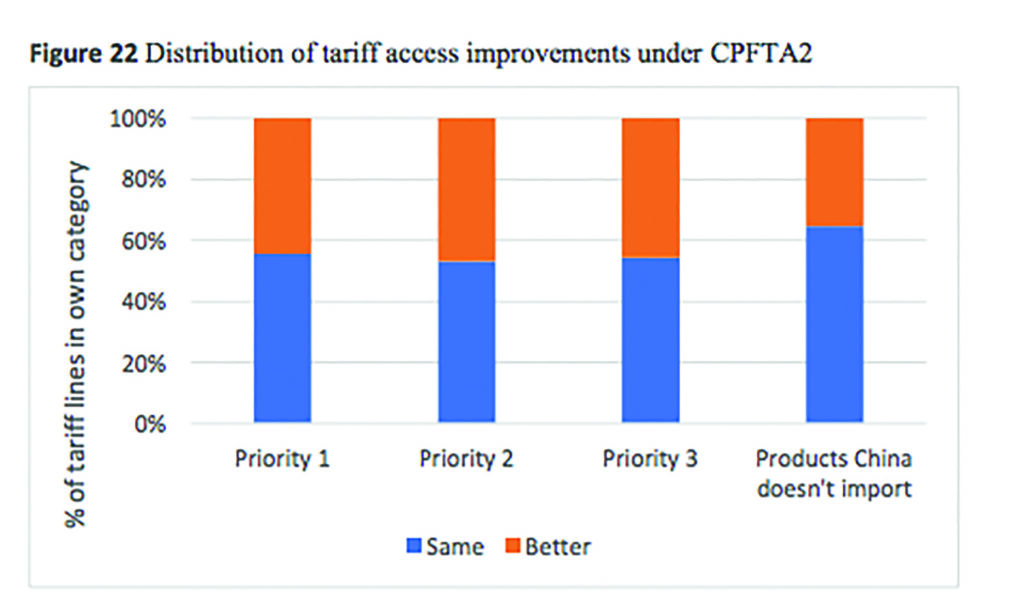

Along the 8,238 product lines that FTA2 effects, Pakistan is now offered lower tariffs on 46% of the products under FTA2, as compared to FTA1.

About 45% of tariff lines, or 3,707 items, have been offered duty free access. A further 30% of tariff lines will have duty-free access by 2030. Additionally, 75% of all products will have zero tariff applied by the FTA’s last year, and 93% of product lines will face a tariff of 10% or less. Only nine out of the 8,238 face a tariff of 30% or more.

Other improvements in FTA2 include standard safeguard clauses, which are a feature of FTAs around the world (one wonders why they were not included before), and real time electronic exchange of data to curtail misreporting.

The report is also hopeful about Pakistan’s competitiveness, claiming that unlike previously where Pakistan’s exports were eroded because of the ASEAN-China FTA, this time around, Pakistan has better access than its top competitors.

What makes this report interesting and relevant, is that it not only shows the difference between the tariffs of FTA1 and FTA2, but also shows how FTA2 could affect three categories of products.

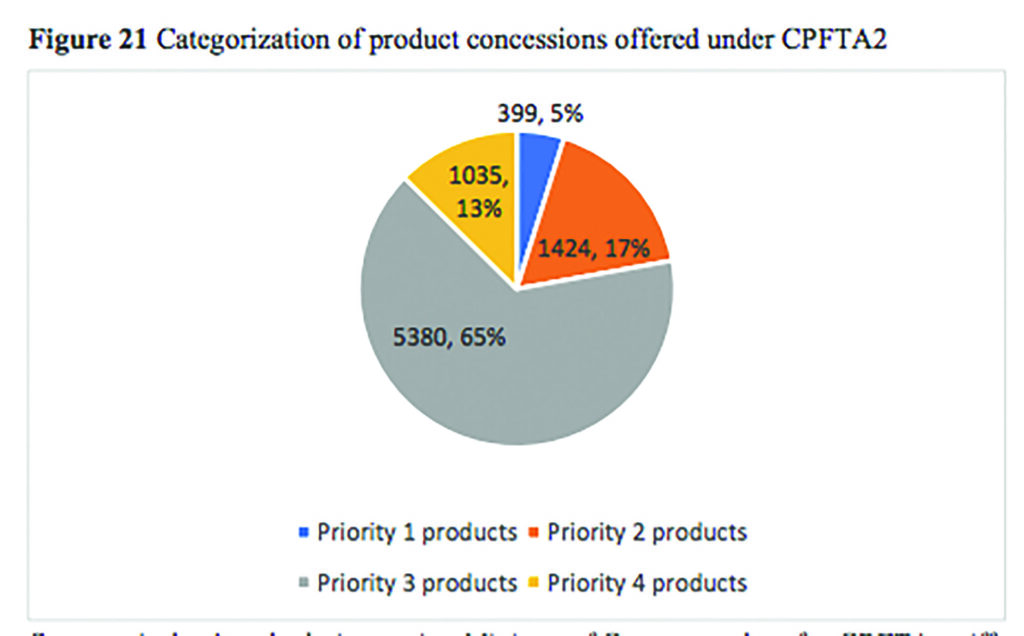

These are: Priority 1 products, or products that Pakistan exports to China (5% of the tariff lines); Priority 2 products, or products that Pakistan exports and China imports, but Pakistan does not yet export to China (17% of tariff lines); and Priority 3 products, or products that China imports, but Pakistan does not export at all (65% of tariff lines).

The second phase of the FTA can positively benefit all three categories, explained below:

- The Priority 1 category contains those Pakistani products that already have an established market in China, and therefore have the highest potential for growth. There are 401 products in this category under FTA2.

Now consider: by the final year of FTA2, 835 of Priority 1 product lines will have duty-free access to China, and 93% of product lines will face tariffs of less than 10%. In total, 445 of the product lines will face lower tariffs under FTA2, compared to FTA1.

Looked at another way: almost $11.5 billion, or more than 80% of Pakistan’s export basket to China will now fall in the duty-free category. This is a sharp increase from FTA1, which only affected $5.7 billion of Priority 1 products.

The winners in this category are cotton plastics, vehicle parts, footwear, leather, and food items like frozen seafood, sweet biscuits, frozen orange juice, machine parts, acrylic polymers, and steel parts.

- Under the Priority 2 category, fall products that Pakistan could take advantage of, since Pakistan is already globally competitive in these goods, and China has an established import market for those goods. There are 1436 products in this category.

Now, under FTA2: 70% of Priority 2 product lines will have duty-free access to China, which is an increase of 575 product lines from FTA1. A full 47% of these product lines will face lower tariffs under FTA2. If Pakistan could expand exports in these goods, it could be looking at an additional duty-free market of $79.6 billion.

Even better: under Phase 2, Pakistan will face better or equal access on 77% of Priority 2 tariff lines, compared to its top five competitors in China.

The winners in this category are machinery and mechanical appliances, steel and iron.

- Under the Priority 3 category, fall potential new exports for Pakistan. The report includes this because this category provides opportunities “to diversify and expand Pakistan’s export offering to the world, starting with China”, under which “new trade creation” can happen.

This is the largest group of products, with 5872 product lines. Of these, 80% or 4701 product lines will have duty-free access to China by the final year of the FTA2. 34% of Priority 3 product lines have better access under the new FTA.

If actually acted upon, the potential winners in this category are accessories of motor vehicles, refrigerators, freezers, heat pumps, woven cotton trousers and woven cotton babies’ garments.

It’s not just about the tariffs

So the Pakistani government has ironed out its tariff structure with China – great! Theoretically under the new FTA, Pakistan is looking to gain not just in the areas where it already has a competitive advantage, but also in new export areas.

So what then is stopping Pakistan from increasing its exports to China? Turns out, quite a fair bit. The report highlights significant challenges to Pakistani exports, some of which are China’s fault, and some of which are Pakistan’s fault.

First, there is a massive information gap about China’s market. As per the report, Pakistani exporters are much more familiar with European and American markets, and less so about China. This is compounded by the fact that there remains a language barrier with regard to China, and adequate resources for translators do not exist. This can lead to issues such as not knowing enough about Chinese regulatory requirements, to also not knowing which Chinese firms to partner with in the event of exports.

This general lack of information also creates an atmosphere of reluctance when it comes to exporting to China. As an example, the report highlighted: “a prominent Pakistani food manufacturer in Pakistan that exported to China was not happy with the Chinese buyer that they partnered with for distribution. After that single bad experience, they have not tried again to find a suitable partner.”

There are also issues on the supply side: Pakistani manufacturers have difficulty delivering on the quantities China requires, mostly due to their own low capital and labour shortage. This lack of scale of production means that Pakistani exporters cannot maintain competitive pricing.

Finally, despite the big fuss created around CPEC, and general ‘close ties’ with China, there is in fact very little trade facilitation between the two countries. As the report notes, “many exporters present had no knowledge of the Pakistan-China Joint Business Council.”

Even when exports are cleared to go, sometimes even routine things like inspections can be destabilizing. For example, the report notes that because Pakistani products are not trusted in China, and there is often unnecessary and annoying inspection of Pakistani packages.

“Exporters of fruit juices reveal that inspections were so invasive that they ruined the packaging which caused leakages and product damage”, the report noted. Additionally, containers from Pakistan often face extra delays and restrictions.

Finally, there is little marketing of Pakistani goods. The theory posited by the report is that as China becomes richer, its consumers will be more discerning about quality. In some cases (such as fruit), Pakistani products are often of a higher quality. But due to the lack of information (because of the lack of marketing), these goods remain overlooked.

To combat these problems, the report has a few suggestions.

These include having a commercial consulate in China, separate from the embassy, whose sole task is to facilitate research on the Chinese market. This consulate could help Pakistani exporters to find suitable Chinese partners who understand Chinese demand, and have the relevant distribution networks.

The report also suggests that the Trade Development Authority of Pakistan create a budget to improve branding and marketing of Pakistani goods.

Another suggestion: that the Pakistani government work closely with China to improve inspections, so that unnecessary enforcement on Pakistani shipments is curtailed.

The report also calls upon the government to help exporters with their weak supply chain, such as “better access to inputs, trade and customs facilitation, and technical support in meeting Chinese compliances”.

Somewhat hilariously, the report also calls on the government to show a little more common sense: “The government should constantly monitor other FTAs that China signs, or any special re-export facilities China offers to other countries.” – basically, to not have a repeat of the ASEAN-China FTA disaster.

Why are these suggestions even important? Because it is not enough For Pakistan to have an FTA with China. To truly maximize the benefits that Pakistan can receive, there needs to be structural reform and admittedly, a little bit of hand holding on the part of the Pakistani government to make sure that exporters are actually able to crack the Chinese market, and receive the benefits of lower tariffs. Until then, one can pick and theorize tariff differentials indefinitely – but the asymmetric trade will not change.

[…] post Pakistan-China FTA: second time’s the charm? appeared first on Profit by Pakistan […]

The Pakistani market is very welcoming to Chinese imports though. They have very easy to use English language websites like aliexpress where you can browse and order products even at retail quantities. Shipping is cheap and hassle free. So with this new FTA we can import even more from China and at a cheaper price!

It doesn’t cost much to create a website but Pakistani exporters can’t even do this much.

Is scanned or colored copy of FTA certificate from China is acceptable in Pakistan instead of original certificate as per new agreement between both countries?

Will it cost any extra duty to the customer in Pakistan if FTA is colored copy instead of original one from China in 2020?

Comments are closed.