It all started, innocently enough, with a beaver. In the middle of last year, British citizen Ben Goldsmith, sitting in London, was struck by a simple question: are there any beavers in Pakistan?

Goldsmith is not your average gora. If his last name sounds familiar to Pakistani ears, you can thank his older sister: Jemima Goldsmith was the former wife of current Prime Minister Imran Khan. And his other older sibling, Zach Goldsmith, ran unsuccessfully as the Conservative party member for Mayor of London in 2016 (losing to British-Pakistani Sadiq Khan, member of the Labour Party).

That is the Pakistan connection sorted. But what is perhaps a little less known to Pakistani audiences is that the Goldsmiths have always been a family extremely interested in the environment. The patriarch, James Goldsmith, was a critic of genetically modified foods, and nuclear power. Zach Goldsmith is the UK’s current Minister of State for Environment and International Development. Ben Goldsmith has been investing in environmental businesses pretty much since he left school – and in 2015, he started Menhaden Capital, a green investment trust (it is named after the Menhaden fish, which filters out impurities from ocean water).

But back to beavers. The animal, mostly found in North America, was nearly hunted to extinction in Europe (though is slowly being reintroduced), and is extraordinarily important when it comes to water conservation. Its presence in rivers is often an indication of a healthy river ecosystem.

To answer his question, Goldsmith turned to his Pakistani friend Farrukh Khan, also based in London. Khan is the founding partner and former CEO of BMA Capital Management. He is also the senior director of business development at Acumen, a non-profit impact investment fund that focuses on developing countries. Most recently, he was named the next CEO of the Pakistan Stock Exchange.

Khan did not know the first thing about beavers. But the Karachi-native called up an old acquaintance, Irshad Adamjee (Khan, a Karachi Grammar School alumnus, and Adamjee, a Karachi American School alumnus, are part of the same extended social set in Karachi, and have known of each other for decades). Apart from being the managing director of Pacific Multi Products, a company within the Adamjee Group, Irshad Adamjee sits on the board of WWF-Pakistan.

In an interview with Profit at his Karachi office, the genial Adamjee was frank about his initial impression of a beaver: “Yeh hota kya hai?” After a bit of googling, and research, he found out (spoiler alert), beavers do not have a natural habitat in Pakistan.

This entire ridiculous chain of events is important, because it sparked another conversation about the environment and Pakistan between the three men. That one anecdote about the beaver got the ball rolling on how to enact effective action against the threat of climate change in Pakistan. The story involves not just Adamjee and Khan’s extensive Pakistani network, but also Goldsmith’s McKinsey contacts, and an enthusiastic Pakistani Ministry of Climate Change.

The end result, around five months later, is the Pakistan Environment Trust (PET), a barely 8-week old company designed to help raise private investment (and potentially have access to government money) to help back green initiatives in Pakistan.

Enter McKinsey

The story takes a slight professional tilt at this point. While the three men were brainstorming potential ideas about what to do for Pakistan, in July Goldsmith reached out to Saif Hameed, Associate Partner at the consulting firm McKinsey & Company’s London office (both are members of the same high school fraternity).

While Hameed had been at McKinsey since 2012, he had a much more interesting stint right before. From 2009 to 2012, he was working as a special advisor to the Government of Punjab on public policy, focusing on among other things, the environment and waste management.

Goldsmith called Hameed to say that he had been at a dinner talking to Adriana Moreira, a senior environmental specialist at the World Bank. Moreira informed him that Pakistan used only a fraction of the climate funds allocated by the Global Environment Facility, a foundation formed in 1992. Her hypothesis was that it was because Pakistan lacked a national fiduciary organization (and one not linked to the government) that could do so. Goldsmith asked Hameed if he would be interested in a project to see what a national fund could look like in Pakistan.

The call could not have come at a better time for Hameed. Just a few weeks prior in June 2019, he had been promoted from Engagement Manager to Associate Partner, which gave him some free time. Plus, he was looking for slightly entrepreneurial things to do, to develop a bit of a presence at the firm.

Just a few minutes after that call, Hameed called the person who leads public sector work at McKinsey, and soon after managed to secure support of McKinsey’s UK Partnership for a pro bono project on the topic. Hameed decided one analyst would be enough to help him.

Muqeet Majed, a 26-year old Business Analyst, who had only worked for two years at the London office, had just booked flight tickets for a holiday in Colombia. On the very Friday he was leaving, he ran into Hameed in the corridor. Hameed told him he was thinking of working on a pro bono project on Pakistan related to climate change. Was Majed interested?

Majed not only canceled his holiday, but ended up in Pakistan for July – “a bit adventurous of me”, he said.

The British-Pakistani had always spent summers in Azad Kashmir, visiting family. The Cambridge grad had also always had a sense of gratitude about his life. “Seeing the kind of challenges that people in Pakistan face, left me with an underlying sense of guilt,” he said. The project was the perfect opportunity for Majed to give back.

The initial pro bono project, led by Hameed and involving Majed, with guidance from Hameed’s mentor Hauke Engel, was focussed on how developing countries like Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nigeria could develop national funds to tackle climate change. That was wrapped up in August.

But because of everyone’s strong Pakistan connection, that project formed the basis of the next step. Majed prepared some slides that were a synthesis of the McKinsey project, which was used during the initial round of stakeholder consultation in Pakistan.

According to the team, “the document highlights the original problem statement/facts that kickstarter our work and a vision for how we aim to drive climate action for Pakistan.”

Hameed, Adamjee, Khan and Goldsmith reached out in their wider networks around late September and early October, and came up with a group of people, well known in Pakistani business circles: Asif Rangoonwala, of South Street Asset Management, Zia Chisti of Affiniti, Ali Raza Siddiqui of JS Bank and Masroor Siddiqui of Naya Management. They, along with others, formed the advisory board for the newly dubbed Pakistan Environment Trust. The PET raised around $250,000 to $300,000 from a pool of around 10 or so investors, to cover operating costs.

The team is now led by Majed, who quit his job at McKinsey in November, and is now working as the Executive Director of the PET in Islamabad. Hameed (who is still at McKinsey) and Khan serve as Board of Directors. Adamjee, Khan, Goldsmith, Engel and Moreira all serve on the advisory board.

The PET premise

So why was the PET actually created, and why now?

Pakistan is one of the top 10 countries most vulnerable to climate risk. Consider the following facts: according to a report prepared by the Asian Development Bank in 2017, in the last 50 years, the annual mean temperature in Pakistan increased by roughly 0.5°C – but by the end of this century, the annual mean temperature in Pakistan is expected to rise by 3°C to 5°C.

Also, the number of heat wave days per year has increased nearly fivefold in the last 30 years, and the sea level along the Karachi coast has risen approximately 10 centimeters in the last century.

As an example, the PET cited some further alarming facts: air pollution has an estimated economic burden of $50 billion, contaminated water has led to the deaths of more than 50,000 children a year due to diarrhea, the wheat yield in Pakistan is expected to decline by 6-9% with a 1°C rise in temperature, and Pakistan has lost 33% of forest cover in just the space of two decades.

On a whole, climate change is expected to cost Pakistan between $6 billion to $14 billion per year over the next 40 years.

Despite these obvious risks, most experts say that Pakistan is also severely under prepared to manage this risk. While a National Climate Change Policy was established in 2012, and is Pakistan’s guiding document on climate change, only about 6.1-8.5% of Pakistan’s federal budget was spent on climate change related expenditures in 2011-2015. The total requirement should be between 8-15%.

Additionally, the NCCP has been criticized for its lack of implementation, though some observers argue that is at least partly due to confusion rising over the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, which devolved many powers down to the provincial governments, which in turn made it confusing as to which powers remain with the federal government, and which ones are now the responsibility of the provincial governments. In addition, there has also been criticism that the NCCP focuses on short term economic growth, as opposed to a long term framework.

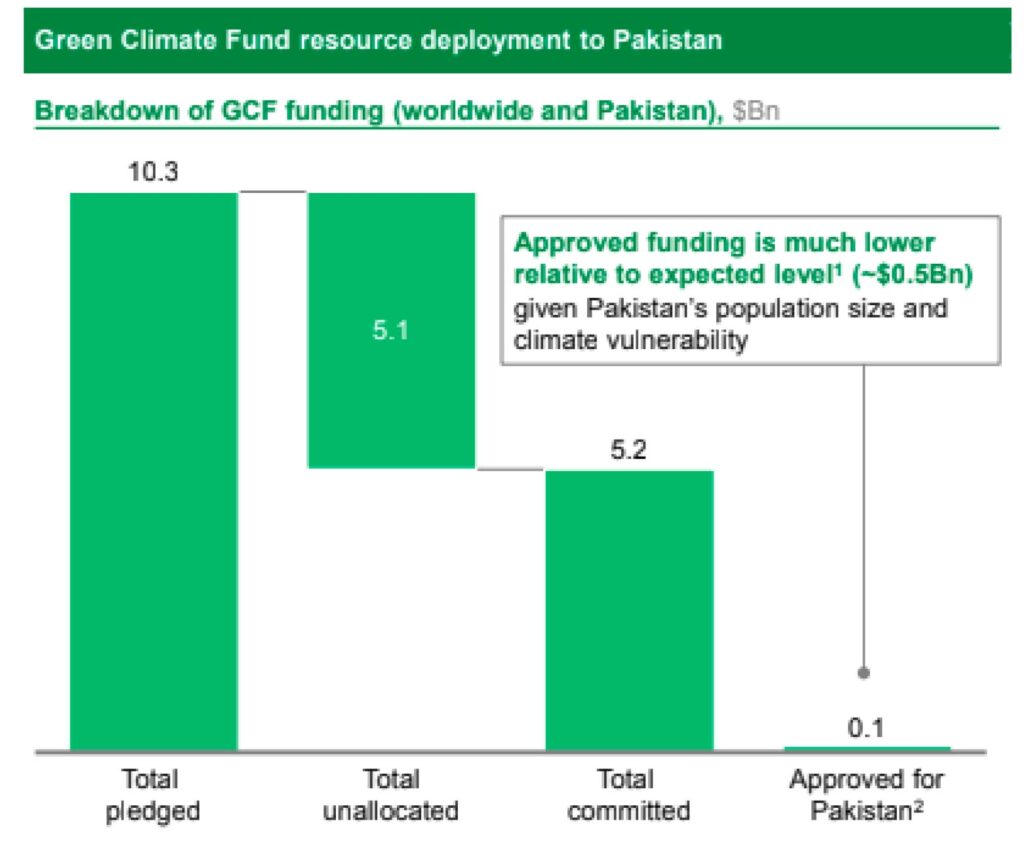

Some good news: some climate finance does exist for Pakistan. The Green Climate Fund (GCF), is an organization that had raised $10.3 billion in pledges from developed countries to combat climate change when it was founded by UN in 2010, and is the world’s largest multilateral climate fund. Recently, it has raised another $9.8 billion as part of its replenishment. Now, the bad news: Pakistan has only utilized $0.1 billion of available funds, mostly due to a lack of GCF accreditation, and poor monitoring of finance flows. Only two Pakistan entities are GCF-accredited, but neither has had a project approved yet.

There is also a severe lack of awareness, and with that a lack of willingness to actually do anything about climate change. As Khan put it, developing countries often have so many basic needs that are unmet, such as a lack of education, or access to healthcare. “You can’t sell a solar lantern to a smallholder farmer, when he’s worried about the next meal – it doesn’t make economic sense,” he said. “But you also can’t keep firefighting, you have to invest in long term initiatives.”

Similarly, Adamjee said rich people in Pakistan care more about education and feeding the poor. But ask them to invest in the environment, “and they take it as a joke.”

And Majed pointed out all the difficulties associated with climate finance. “You have all these numbers being thrown around, but it’s actually very difficult for a developing country to navigate this space.”

The PET is an attempt to answer all the above problems: to have a solid advisory board and a team of seemingly competent people that will attract both local and foreign confidence, and that can act as an intermediary between international investors, organizations, and the Pakistani government. It basically aims to be the impact investment advisory organization in this space.

According to PET documents: “Beneficiaries of global environment funding typically have a structured independent mechanism to distribute funding locally. Our analysis suggests that an independent National Environment Fund could help develop these factors.”

The team identified that there is a need for a dedicated national entity that develops and submits projects that align with standards of large international financiers like GCF, and with the goals set out by the government of Pakistan.

The PET has three main goals:

- Identify, develop and where necessary incubate fundable projects based on a country level blue-print of priorities.

- Attract, structure and deploy funding from a range of sources including equity, grants and loans.

- Support the scale-up of initiatives by leveraging global expertise and managing stakeholder relationships.

The PET will have a blended financing model to fund projects, and overcome the climate finance gap. A potential project could be funded initially by a philanthropic grant, with subsequent funding coming from a combination of both debt and equity from development finance and the private sector.

Enter the government

In the attempt to get the PET some serious recognition, the team reached out to the Ministry of Climate Change, headed by Malik Amin.

Within Pakistan, Amin is most famous for his somewhat gimmicky ‘Billion Tree Tsunami’ afforestation program. But Amin has also served as a private consultant to the World Bank and the UN on the environment, and is genuinely quite motivated.

Hameed had previously called Amin to brief him on his idea while on holiday in Paris in September. Then in early November, Hameed and Majed flew to Islamabad to meet Amin. The meeting proved a fruitful one: Hameed recalls being impressed by Amin’s punctuality (“especially after having worked in the government before”), and Amin was impressed with Majed’s slides. Within a few minutes the three were talking about areas of potential interest and collaboration.

Since at least October of last year, Amin has been promoting a five-point green agenda. This includes the 10 billion tree tsunami, a plastic ban, an electric vehicle policy, a clean green index and ‘Recharge Pakistan’ (which tackles floods). He reiterated these points at the UN Climate Change Conference, or COP25, held from 2 to13 December 2019 in Madrid.

Almost in parallel to the formation of the PET (but not related), the government set up a fund, Ecosystem Restoration Fund (ESRF). This was launched at COP25, and is around $120 million provided by the World Bank.

The ESRF is a fund that sits within the National Disaster Risk Management Fund (NDRMF), an older pre existing fund that has close to $300 million within its ambit, much of it provided by the ADB.

While it is still a moving picture, and the ESRF and NDRMF relationship still has to be sorted out, the idea is that some of that public money can be used towards the PET.

As far as Amin is concerned, any Pakistani who cares about the environment is good enough for him. He also gave a little bit of a PTI spin: “I think it really speaks to the confidence expats and diaspora have in our Prime Minister – they want to be a part of the story”.

PET and Amin have cultivated a strong working relationship, so much so that for now Majed’s office is on the first floor of the Ministry of Climate Change building in Islamabad. When asked whether this might seem a little too politically motivated, Majed responded that they were trying to make sure PET had a good working relationship with the government, so that their goals complement one another, and there is little overlap,clarifying that they are in the process of establishing their own office in Islamabad.

Interestingly, the PET did mention they had reached out to other political stakeholders, to maintain good ties, perhaps post PTI (though they did not reveal names).

One group the PET did little to foster a relationship with? Climate activists working in Pakistan. The team seemed uninterested in pressure groups like Climate Action Now, for instance (though they had heard of it), and mentioned having once spoken to people like Rafay Alam (a prominent environment lawyer based in Lahore, with an active Twitter presence), but that was the extent of it.

In conversations with sources, and the people mentioned here, one element that stood out the most ‘McKinsey’. Both Amin and Adamjee, for instance, seemed impressed with the fact that Hameed and Majed were from McKinsey. Hameed and Majed, for their part, did drop consulting jargon in conversation – even the slides on the PET were designed with McKinsey principles in mind, right down to using the same arrow font and design in some sections.

“I definitely bring the kind of toolkit that I used at McKinsey,” said Majed. “That kind of analytical mindset that can break down problems into its logical conclusion.”

To be clear, the PET is not a McKinsey project. But Profit brings it up to emphasize that it is part of a larger trend of expats with impressive, always foreign credentials, taken at their word (consider PTI’s rollout and emphasis on the fact that Tania Aidrus, the digital spokesperson for Pakistan is an expat who used to work at Google). That often leads to accusations that Pakistani expats are out of touch.

And PET is definitely led by a global and privileged bunch: many of the members live in London or Washington DC (or can travel easily from Karachi to those places), and Majed himself was speaking from Liberia (where he was helping the GCF) during the time period for this article.

In response to this concern, Khan was dismissive: “It would be great if locals took responsibility, then no one from overseas would get involved.” Amin was cautious: “Expats do come with a perfectionist mindset, they often have to adjust to a different reality [of working in Pakistan]”.

But the most self-aware defense came from Majed, as the youngest member of the team, and the one actually on the ground in Islamabad: “I understand that some of it can be seen as just superficial. But look, moving from London to Islamabad is not easy,” he said. “It’s a pretty big shift and work like this is incredibly challenging. There is a risk of being perceived as an outsider, that you’re not in it for the long haul.”

PET, as everyone wants to make clear, is definitely in it for the long haul.

Moving Forward

So what’s next for PET? Quite a few things, actually.

The first project development: PET will finalize 1-2 high-potential, fundable project concepts from and initial shortlist. It will then create a high-level business case for a pilot project in February 2020, and raise seed funding in April. These projects will fall under a specific point of the government’s 5-point agenda.

The second is an entrepreneurship competition, that will help incubate high potential projects that focus on agriculture, waste, energy and water. This competition will be designed in February 2020, and submissions will be open in March 2020. Entries will be evaluated in September, while winners will be announced in October. The winners will receive a cash prize of $40,000 in funding to develop their idea.

Third, the PET will help create a documentary series. A promotional video will be launched in March, while the series will tentatively be launched in July 2020. Each 10 minute episode will highlight a specific priority issue – agriculture, energy, forestry, waste, water – to build awareness.

Finally, PET is also looking to hire folks, to help out with the GCF co-chair, and also full time hires and interns for Islamabad, to help out Majed with the growing pipeline of activities. At least one senior consultant from a top tier company is joining PET, starting in March.

If the goals sound a bit hazy, that is because the trust is still in its nascent stage – a bank account was only set up in January, and some legal requirements still have to be ironed out. But if in 20 years time – or 50, or 100 – Pakistan will actually have risen to the challenge of climate change, and become a truly eco-friendly and sustainable country, we can all partly thank the PET – and the beaver.

[…] post Can the Pakistan Environment Trust get the country to take climate change seriously? appeared first on Profit by Pakistan […]

Thousands of words about the old boys clubs and connections in London make it sound like a vanity project for rich expats

Comments are closed.