In 1960, Pakistan made the momentous move of shifting its capital from Karachi to Islamabad. Establishing a new center of power and governance is a herculean task in itself, but it was a doubly impressive feather in President Ayub Khan’s cap that the city that was to become Pakistan’s capital was built from scratch.

Rome may not have been built in a day, but Islamabad was built in four years. The magnum opus of celebrated Greek architect Constantinos Apostolou Doxiadis, the founder of ‘Ekistics’ and one of the fathers of the modern city, Islamabad at the time of its founding was the city of the future.

Nestled in the Margalla hills, Islamabad ‘the beautiful’ was conceptualised as a symbol of unity in an ethnically and geographically divided country, and a flag bearer of modernity. But what was envisioned as a cutting edge, sleek, modern capital has since become the victim of insufficient public utilities, lack of affordable housing, commercial and office space, decaying public infrastructure, illegal and haphazard development and mushrooming slums in addition to a rapidly rising cost of living, that disproportionately affects lower income groups.

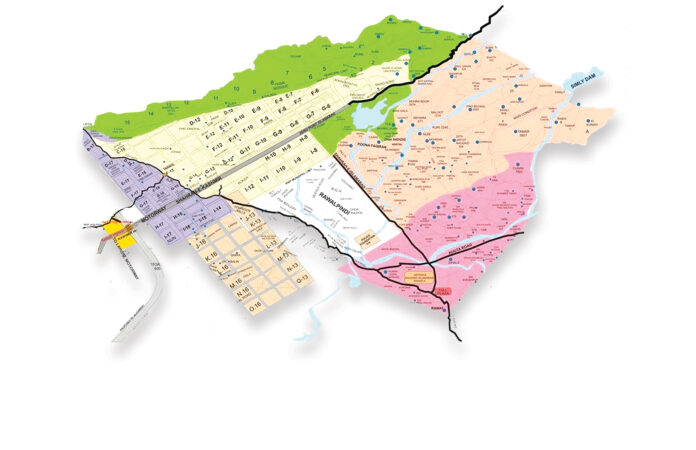

At the center of this fascinating city that was practically willed into existence is the Islamabad Master Plan. A document that has, in recent times, come under vociferous scrutiny. Its supporters are willing to live and die by it, and its detractors fear it has become redundant and needs revising. With the master plan also came the Capital Development Authority (CDA), which first took charge of the city and its five meticulously laid out zones in 1960.

In 2017, the Supreme Court of Pakistan (SC) took Suo Motu notice of irregular development in Islamabad and directed the government to find a solution for regularizing these constructions. Later, the Islamabad High Court (IHC) in its judgment dated July 9, 2018 directed the government to form a commission to review the Islamabad Master Plan. Consequently, a commission was formed in August 2019 to review the master plan and give its recommendations.

But the commission simply gave recommendations to gloss over the issues in its attempt to maintain the original spirit and architectural integrity of the city. With Islamabad at war with itself over whether to expand to its full potential or continue to cling to its wealthy suburban roots, we look into the short but rich urban history of the country’s capital, and see whether another master plan is needed to revive a city fast losing touch with its character and purpose.

Or for that matter, whether these grand, ‘master plans’ have simply become unviable relics of the past. And if that is the case, how exactly should the city be managed?

Islamabad – an urban planning history

Islamabad was planned as a low density, no-nonsense, administrative unit. But when the city was being formed, Doxiadis was more than just its architect designing roads, buildings and avenues. He was more of a development consultant, building not just the city, but mapping out its future at the same time. And for him, Islamabad could be nothing other than a modern, urban, space.

Scholars of history are often critical of the way cities are presented on maps and in designs by developers and architects that wish to fix them by moving lines on a page. Cartography, after all, is a naturally violent process. When it is exerted upon ancient cities such as Lahore and Peshawar or bustling centers such as Karachi, they do away with the pulse of the street. The streets, as they exist outside of maps, are vascular; if you cut them they bleed.

This is exactly what made Islamabad such a unique experiment. It had none of the scruples of ancient civilizations still haunting its core or colonial customs ruling the roost. It was an opportunity for a clean slate city, one where governance could be different along with city planning. Perhaps the street would not have the same vitality in the beginning as in older cities, but they would be clean and fresh. A beautiful, idyllic space for its new inhabitants to make of it what they will.

At the center of this spirit with which Doxiadis planned Islamabad was the city’s grid iron pattern. There is, fundamentally, a grid dividing the city into 84 sectors, each 4 square kilometres. The other is the ‘natural’ grid created by ravines flowing through the entire site area. Each sector has five sub-sectors – four residential and one commercial (Markaz) – which is encircled by auto routes with pedestrian networks within the sector. Each of the sectors would be low slung and consist of single-family homes, American suburb style.

But the plan that Doxiadis envisaged was restrictive, and clearly could not even have dreamed of how many people would migrate to Islamabad and how extensive the city would get.The master plan included nothing about zoning for the poor, or a city center, a commercial business district (CBD) for that matter.

The vision was definitely futuristic. Cleanly mapped streets with sectors that had everything you would ever need and thus there would be nothing that would require you to over go anywhere outside of your sector. It was all rather mechanical, and the approach was perhaps summed up best in that no office spaces were created apart from the secretariat, and the master plan did not include any plans for expansion. After all, Islamabad was to be a small scale center for governance, with bureaucrats, politicians and government functionaries occupying its homes for the most part.

What happened instead was in-migration has happened far faster than envisaged and Islamabad now has more than 2 million inhabitants. While the CDA and the courts have generally tried to stay true to Doxiadis’ plan, simply stretching and tweaking it when needed, the master plan continues to suffer from its birth defects: no CBD, no room for the poor, and no elongated car dependence.

Where the plan went wrong

It really is not Doxiadis’ fault however, it is simply the nature of master plans everywhere. The problem is, Islamabad’s population has grown far beyond what was once imagined, and it has become a diverse city in terms of the economic and social disparity between its inhabitants as well. However, the desire of the CDA to remain true to the original vision has meant that Islamabad has been over-regulated, limiting both the social and economic potential of the city. The land and building regulations are too rigid, and have resulted in contrived urban development and stifling of economic activities.

As Islamabad grew naturally, the ghost of Doxiadis and his master plan continued to haunt the city, stifling the way it would have grown naturally. Even as the street’s of Islamabad gained the pulse that Doxiadis wanted to avoid, the master plan tried to nip it in the bud – policing the natural growth of the capital from the past.

Where the situation currently stands is that Islamabad has the problem of a significant urban sprawl owing to unrestricted growth in housing schemes and roads over large expanse of land, with little concern for urban planning. At present, the housing backlog in the 2 million strong city is about 100,000 units. This gap is expected to increase by 25,000 units per year, while the current supply of houses is growing at about 3,000 annually. Despite these shocking numbers, the CDA has not launched any new residential sector in the past twenty years. The last sector was launched in 1989, and has not seen any development since then.

The fact of the matter is that there are barriers to sustainable urban development in Islamabad, and part of the problem lies in restrictive zoning that encourages sprawl and single-family homes against high-density mixed-use city centers and residential areas – more in line with the Euclidean zoning which favors single-family residential as the most preferable land use. This leads to inefficient use of land which is a premium asset for any city.

Because of these barriers, Islamabad has become the victim of an urban sprawl, an issue that plagues the modern city and developers. An urban sprawl is essentially the expansion of a poorly planned, low-density, automobile-dependent development, which spreads out over large amounts of land. This puts long distances between homes, stores, and work and creates a high segregation between the residential and commercial uses, with harmful impacts on the people living in these areas.

One would be painfully aware that the entire design of Islamabad was such that people were able to access all necessities within their own sector and not have to venture out of it. When high levels of migration to Islamabad happened, the naturally occurring urban sprawl came in conflict with this philosophy.

The best way to fight this urban sprawl would be to move towards densification of urban areas beyond the core parts of the city. The question, essentially, becomes one of horizontal development versus vertical development. In lay terms, population density is the major driving force of horizontal urban expansion, while fixed investment is the major driving force of vertical urban expansion for the city as a whole.

Densification is a kind of vertical growth that would be against Islamabad’s master plan, and is not an easy task to pull off. However, it is a challenge worth taking on since it leads towards the goal of compact city development. After all, while Islamabad may have been designed in a very particular way, at some point the question has to be asked, are cities made for people or vice versa?

Are master plans a relic of the past?

All of this indicates the need to shake things up from the master place. Densification and changing zoning laws are needed to look after the needs of what Islamabad is fast becoming: a 2-million-strong metropolis. This is where the earlier mentioned Federal Commission for the Review of Islamabad Master Plan, set up by the IHC, should have come in.

Instead, what they did was double down on the 60-year-old plan. The recommendations of the commission continue to look after cars, and to restrict the development of high-rises while hanging onto the suburban model. This was simply an oversight of the fact that Islamabad is no longer a quaint suburban city or a summer capital. It is the seat of power as well as a growing metropolis in its own right.

The commission’s recommendations appear to be oblivious to the needs of the homeless and the needs of the growing metropolis of over 2 million people. But other than their same-old-same-old recommendations about engaging consultants and broad ideas, the commission managed to do very little. In short, after about sixty years since the first plan was made for Islamabad, the city is awaiting a plan that will solve its current problems.

The problem of master plans is a pertinent one. Planners unfortunately are willing to knock down buildings, through court injunctions no less, for being a couple of feet higher than suffocatingly stringent regulations. However, just because planners wish to stick to a more than half century old plan does not mean that the existing nature of the city changes. In fact, when life does not adjust to the old ways, cities and their residents end up in years of strife. That is the reality Islamabad is staring down currently.

Master plans had their place in the world at one point, in fact, they were the modus operandi for how to build cities after the destruction of the Second World War. However, they have fallen out of favour for some time now and for many reasons.

Master plans use present and past data to chart out the trajectory of a city for the next two decades. And while this is a scientifically sound method, it does not take into account the possibility or space for change that may be needed for any reason, and particularly because people are unpredictable. The plans are also static in nature, based on unrealistic assumptions, rigid, and dictate how markets should develop leaving no room for them to find their own level.

But even as the world sheds itself from the constraints of these master plans, in Pakistan, master-planning seems to be an inside job between planners and builders to stay in business. Public participation in the planning process is often perfunctory or nonexistent. These plans, therefore, are never owned by the community nor do planners recognize the needs of the people.

Rethinking the city

The most basic and important argument to allow a city like Islamabad to grow instead of to box it in under countless regulations is that it must be treated as a market. Conceptualising the city as a market that facilitates economic growth means that to help the economy grow, the city must be allowed to grow as well.

As Nadeemul Haque, currently the vice chancellor of the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, argued in his Framework of Economic Growth, cities are born out of markets, since markets create order, which manifests itself in the form of cities, based on price signals. And if these basic market units are to help the economy grow, they must be allowed to grow too. Cities that drive productivity and growth are neither neatly planned nor laid out for suburban living and cars. It is the seeming chaotic nature of these cities that drives their productivity and growth.

It is for this very reason that many cities are moving away from master plans to guidelines and rules that allow the needs of the market and investors to determine what should be built. The city planner only worries about social and community needs, public health and safety and other common issues but not with regulating everything in the city, or the economy for that matter.

In addition to this, the city itself must be seen as a source of wealth, not to exploit, but to uplift its inhabitants. Cities often sit on a gold mine of assets that include not just real estate and public utilities but can also create wealth through socio economic uplift of its people and regeneration of decaying urban areas. These assets can be materialized through better city management (Detter and Fölster 2017).

The world is already moving on from restrictive master planning, and it is becoming apparent that the Islamabad Master Plan was a flawed exercise from the very start, made even worse by not reviewing and updating it after every 20 years.

Even as Islamabad fights a status quo that will not allow it to breathe, there are newer methods like neighbourhood planning that are used across the world, and should be employed in Pakistan as well. There is no doubt that the capital is an over-regulated city. It is also not an affordable city for low-income groups to reside in. As the master plan finally goes into the process of being re-evaluated, our suggestion would be a complete paradigm shift in our approach to city management – a shift that should be applied to other cities in Pakistan as well.

Adapted from the PIDE report by Abdullah Niazi

I didnt read it all

Comments are closed.