Some time in the next two to three years, possibly even this fiscal year, something extraordinary will happen: for the first time since at least the completion of the Tarbela dam in 1976, a majority of Pakistan’s electricity generation will come from imported primary fuel sources rather than domestic ones. Needless to say, this has profound implications for the cost of energy in the country, and the government’s management of the economy.

The biggest impact of this shift is one that we see crudely playing out on the nightly opinion talk shows on television: volatility in global oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG) prices have a significant impact on the price of energy in Pakistan.

Of course, the mouth-breathing cretins who constitute the class of people we in Pakistan call ‘television journalists’ (barring a handful of notable exceptions) are engaged in the most meaningless possible discussion about the topic, so we do not want to dignify them by suggesting that they are discussing anything remotely important. They are not.

But there is still a bigger issue at play here: the next decade will be a highly volatile one for Pakistan when it comes to electricity prices. If we are very, very lucky, global energy prices for oil and gas will remain relatively low (ideally below $60 a barrel for crude oil) and thus we might be able to skate through this period relatively unscathed. But to be reliant on a full decade of low energy prices is a bad place to be as a country, especially one whose public is used to cheap domestic sources of energy.

This story will explore three questions: how did we get here, what is the outlook for the next decade, and what can be done to ensure that we get out of this situation?

Rarely for Pakistan, this also appears to be one area where the government and private sector appear to be on track to solve the problem – provided we do not veer off track. Both the current Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI) led administration and its predecessor Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) led administration have put in place both policies and projects that appear to be on track to result in Pakistan’s energy mix getting both cleaner and less import-dependent over the next ten years.

But that is nearly ten years from now. Today, we still face a difficult situation. Let us take a look at how we got here, and what it all means.

A very brief history of Pakistan’s electricity sector

The first Pakistani city to get electricity was Lahore, when the Lahore Electric Supply Company (LESCO) was created in 1912. Karachi got its electricity a year later, in 1913. Electricity generation back then was mainly thermal power plants reliant on either coal or oil. This remained the dominant source of electricity in what is now Pakistan for most of the next five decades.

The game changer for electricity in Pakistan – and therefore the whole Pakistani economy – was the Indus Water Treaty of 1960. At Partition, the matter of which country would get use of how much of the Indus River System – which existed on both sides of the border – was not settled, resulting in a dispute between the two countries.

With mediation from the World Bank, India and Pakistan agreed to split the use of the system under a proposal first developed by the American lawyer, David Eli Lilienthal, with the treaty signed by President Ayub Khan and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru at Karachi in September 1960.

Why did this matter? Because it functionally resolved nearly all of the disputes between India and Pakistan over water and meant that any hydroelectric power project on the Pakistani side of the border could get international financing without fear of being dragged into international litigation, or worse, a border conflict. While India and Pakistan have gone to war – including three times after the treaty was signed – it has never been over water, and the treaty remains unbroken.

Having resolve the territorial conflict over water resources, Pakistan could begin construction on hydroelectric power projects and almost immediately began working on the Mangla dam, on which construction started in 1961 and ended in 1965. The much larger, and more ambitious Tarbela dam was constructed between 1968 and 1976.

It is worth pausing to take stock of just how big an achievement it was for Pakistan to have built these dams. Tarbela was the largest mud-filled dam in the world, and at the time of its construction was the fourth largest hydroelectric power project in the world.

But here is the truly mind-blowing fact about these two dams: if every single coal-fired power project in Thar came online today, all of them combined would produce less electricity than Tarbela and Mangla. Yes, these two dams that saw most of their construction completed in 1976 (the most recent extension project on Tarbela was completed in 2018 and another one will be completed by 2024) produce more power now than Thar Coal will produce ten years from now.

These two dams – and the spree of dam construction that followed over the next two decades – meant that the bulk of Pakistan’s electricity needs were met by clean, domestically produced hydroelectric power plants. Yes, in the 1980s, the government began setting up oil-fired power plants, but the vast majority of Pakistan’s electricity came from water until at least the early 1990s.

At that point, with international financing difficult to procure owing to Pakistan’s poor relations with the United States, the government instituted a policy that allowed for more private sector players to set up independent power plants (IPPs) that were reliant mainly on oil. Over the next decade, this increased Pakistan’s reliance on imported oil as a fuel for its electricity generation.

In the early 2000s, the Musharraf Administration decided to convert at least some of that thermal power generation capacity from imported oil to domestic natural gas, under the assumption that Pakistan had abundant domestic reserves. (This, as has been pointed out in this publication on many previous occasions, was a very faulty assumption.)

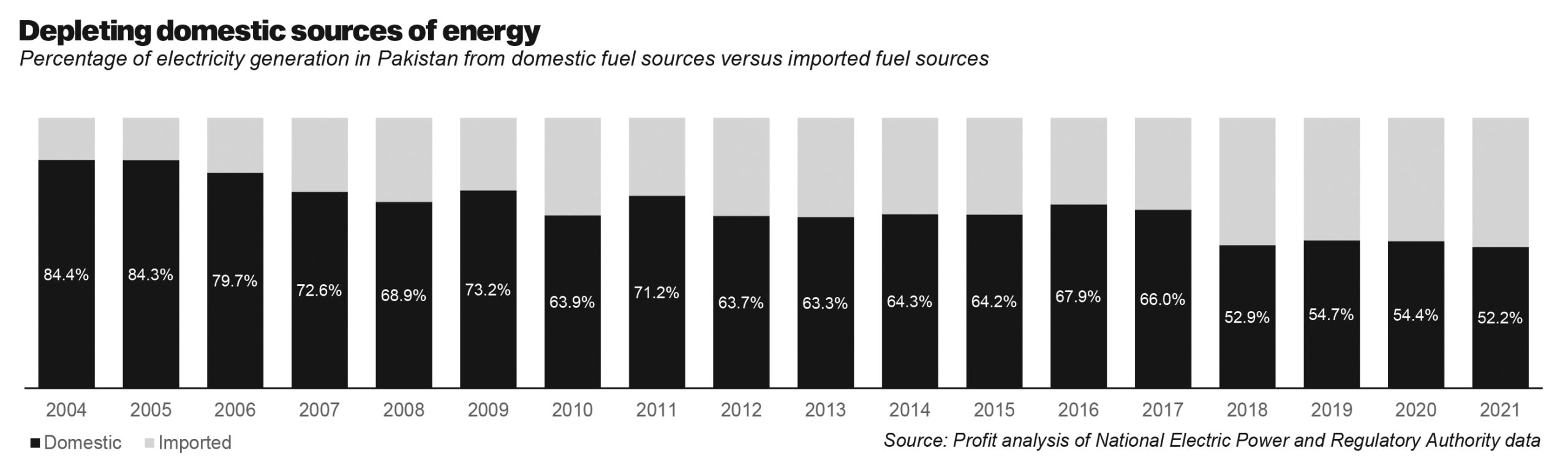

As of 2005, the height of the Musharraf-era economic boom, Pakistan derived more than 84% of its electricity generation from entirely domestic fuel sources, according to Profit’s analysis of data from the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA). That meant that even as the Iraq War of 2003 drove up global oil prices, Pakistani consumers of electricity remained largely unaffected.

Unfortunately, there was a limit to just how much natural gas was available in Pakistan and around the end of the Musharraf years, Pakistan went from being a gas-surplus country to having a shortage. That shortage, in turn, meant that the thermal power plants that could run on either natural gas or furnace oil ended up having to run on oil almost all of the time as the government scrambled – and failed – to keep the lights on.

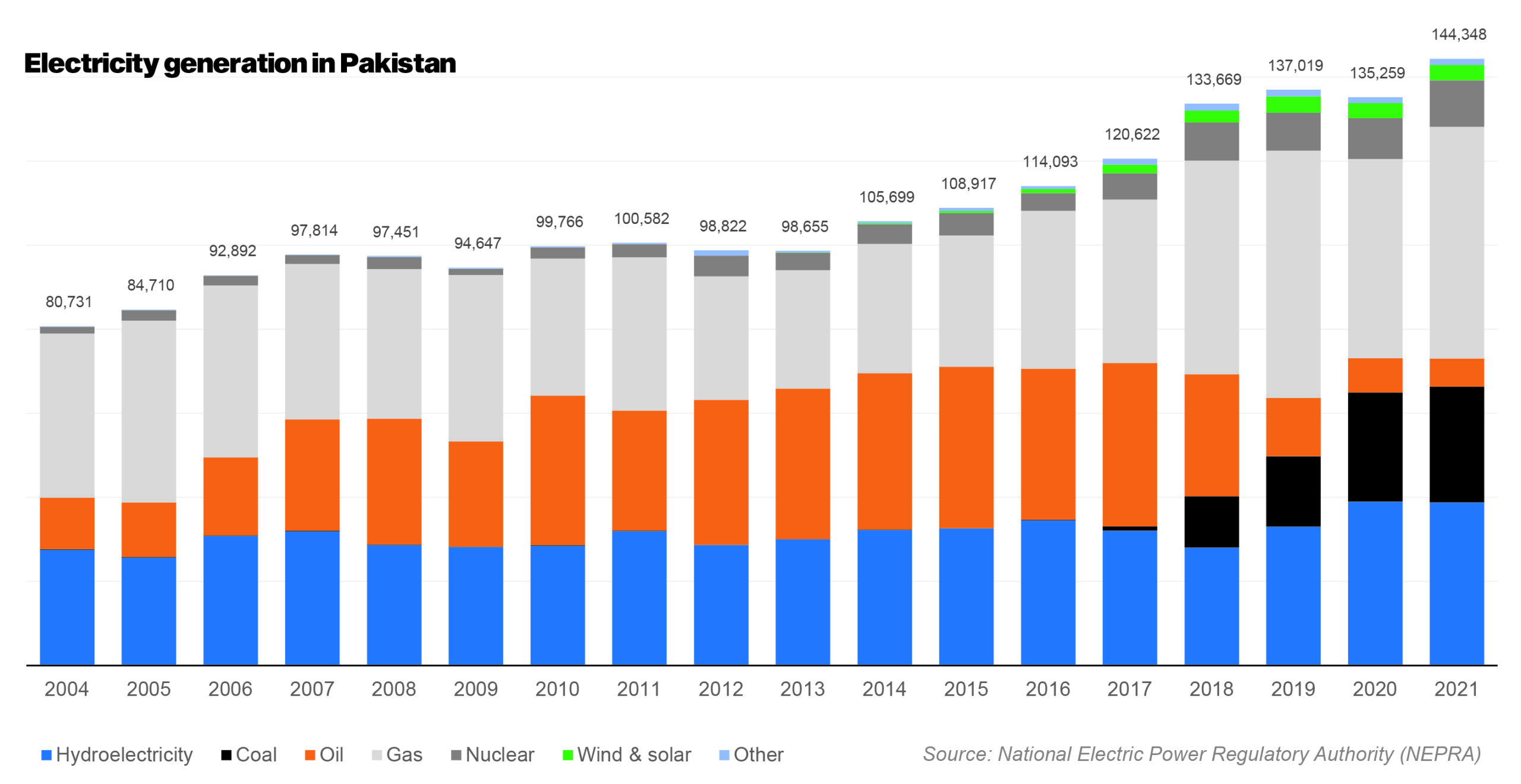

Look at the charts for Pakistan’s power generation. The orange part of the bars that represent oil-fired power starts growing larger in 2006 and keeps growing larger almost uninterrupted until it peaks in 2017. That period also coincides with rising oil imports, which kept on rising in volumetric terms during this period, though they declined in dollar terms from 2013 onwards with the sharp decline in global oil prices.

The sharp rise in reliance on oil coincided with a dramatic rise in oil prices themselves (late 2007 and again in early 2009). Oh, and the rupee’s value collapsed at the same time, which created a perfect storm for the incoming Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) led government, which did tried to keep consumers insulated by increasing government subsidies, but the government did not have the money to do so.

The whole energy industry entered a massive financial crunch as the government’s failure to pay subsidies meant that power companies could not pay the oil importing companies which in turn could not pay their international suppliers, which meant that the country frequently ran out of enough oil to keep the power plants running. The PPP-led government was utterly inept at trying to resolve the problem that resulted in 12-hour daily power outages even in major cities, and even longer in rural areas.

So, when Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif came into office in 2013, he knew he had one big problem to solve: energy.

The Nawaz legacy on energy

The PML-N strategy was reliant one big thing above all else: build lots and lots of power generation capacity, build nearly all of it on coal-fired plants, and build it all very, very quickly. In many ways, this strategy worked: between 2013 and 2019, Pakistan’s power generation capacity rose nearly 64%, from 23,825 megawatts (MW) to 38,995 MW, according to NEPRA data.

In order to get the capacity to rise that quickly, however, the Nawaz Administration offered overly generous contracts to private sector energy companies and agreed to allow the building of power plants that relied on imported coal. [An interesting fact: nearly all of Pakistan’s coal imports come from South Africa and Indonesia.]

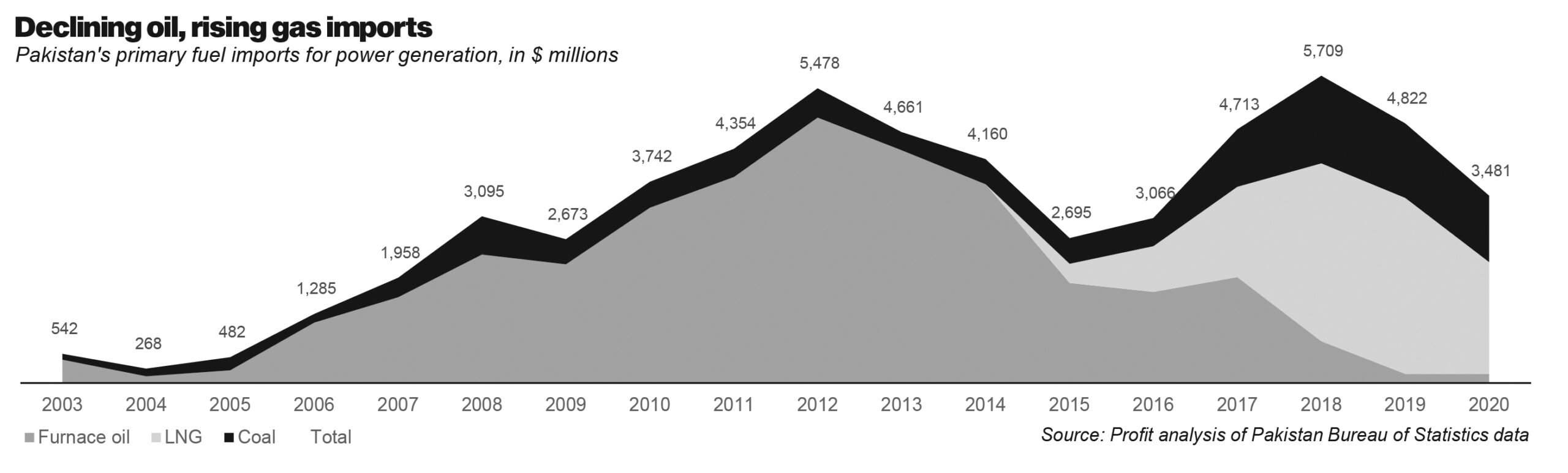

In addition, the Nawaz Administration took a hard-nosed look at Pakistan’s domestic gas supply and decided that the country needed to begin importing natural gas as well. It allowed private sector companies to set up LNG import terminals. That meant that the thermal power plants that could no longer run on domestic gas could now run on imported gas rather than imported oil. This change had the effect of both reducing Pakistan’s import bill (even LNG is cheaper than furnace oil) and reducing carbon emissions (burning gas emits less carbon dioxide than burning oil).

Both of these policies meant that Pakistan’s imports of furnace oil dramatically declined, but its imports of LNG and coal went up. The overall energy import bill for electricity generation declined by about 36% between 2012 and 2020, mainly because both coal and LNG are cheaper than oil, and because Pakistan was able to secure a very good price on LNG from Qatar.

The Nawaz Administration was criticised heavily for the high price it paid for that increase in power generation capacity, including by this publication. However, it appears that much of that capacity is already being used. While power generation capacity rose by 64% over the past eight years, actual power generation rose by over 46% during that same period, suggesting that bulk of that new capacity is being utilised.

And while the import bill for Pakistan’s power generation has declined even as the country’s reliance on imported fuels has gone up, that is largely the result of a relatively benign global energy price environment. That may last a while longer, but it cannot last forever, and if global prices start to rise again, Pakistan’s energy bills will be much more vulnerable to rising with them than ever before.

It is a classic Faustian bargain: a rapid increase in electricity generation capacity that is cheap for now, but will likely start to get expensive later.

However, the Nawaz Administration did one other thing that will likely help the country’s energy system: it began work on the Dasu dam, the first near-Tarbela-sized dam to be constructed in Pakistan in nearly 50 years. While the Nawaz Administration ultimately halted work on Dasu in 2017, the Imran Khan Administration was able to revive the project when it came into office a year later, and it is now on track for completion by 2025.

But more on why Dasu matters later. For now, let us examine the consequences of this deal with the devil.

A rough decade ahead

As a result of the increased reliance on both imported coal and LNG, Pakistan now generates just over 52% of its electricity from purely domestic sources as of the fiscal year ending June 30, 2021, according to Profit’s analysis of NEPRA data. That is down from over 84% in 2005, and 71% as recently as 2012. This stark decline in domestic energy sources makes Pakistan more vulnerable to both changes in global energy prices as well as increases the negative consequences of the government’s poor decision-making on trying to control the currency exchange rate.

A reliance on imported energy is not inherently a bad thing. If the economy can reliably produce electricity using imported fuels, and its electricity grid can continue to serve the economy’s growth needs, imported fuel might even be a good thing. But the problem is that imported fuels makes changes in prices something the government of Pakistan cannot control, which means they will tend to get panicky and make all sorts of bad decisions about economic management.

How will this play out? Picture the following scenario. Global energy prices start to rise, which – given the level of dependence the country has right now on imported energy – will mean a considerable strain on the country’s current account balance. That strain will start to affect the value of the rupee. The government will try to protect the value of the rupee by borrowing more money from foreign lenders and simultaneously either decreasing taxes on petrol or increasing subsidies on electricity.

Both of these will have the effect of exacerbating the fiscal deficit, leaving the government more vulnerable financially even as it has taken on more debt obligations in US dollars. Meanwhile, the government’s deteriorating fiscal health will mean that foreign lenders will stop wanting to lend more money to the government of Pakistan, which will decrease its ability to keep the rupee stable. That means the rupee’s value will start falling, just as the loan payments to those foreign lenders will come due.

Repaying those loans will both further decrease the value of the rupee, and cause an increase in inflation as the rise of global energy prices will be exacerbated by the rise in the price of the dollar. Except instead of happening gradually, this will now all happen suddenly, in the span of one calendar year.

Because the government will have artificially held the rupee’s price up, when it eventually has to let go, it will fall both faster and deeper than it would have had the government simply allowed it to happen gradually. Inflation has a way of collecting its due, and there is nothing the government can do to prevent that from happening.

Of course, the government could try not being stupid and when energy prices rise, simply pass them on to consumers. But that would mean that the screeching banshees on television would start yelling themselves hoarse about the “petrol bomb” or “crushing inflation”, which would scare the government into doing precisely the thing that will make the problem worse.

Here is where things get truly scary: in order to manage the fiscal deficit, one of the first things the government cuts when energy prices start to rise is the development budget. That is where the money for the construction of hydroelectric power projects like the Dasu Dam (and hopefully the Diamer-Bhasha Dam) will come from. And those are the key to solving this mess.

How the problem gets solved

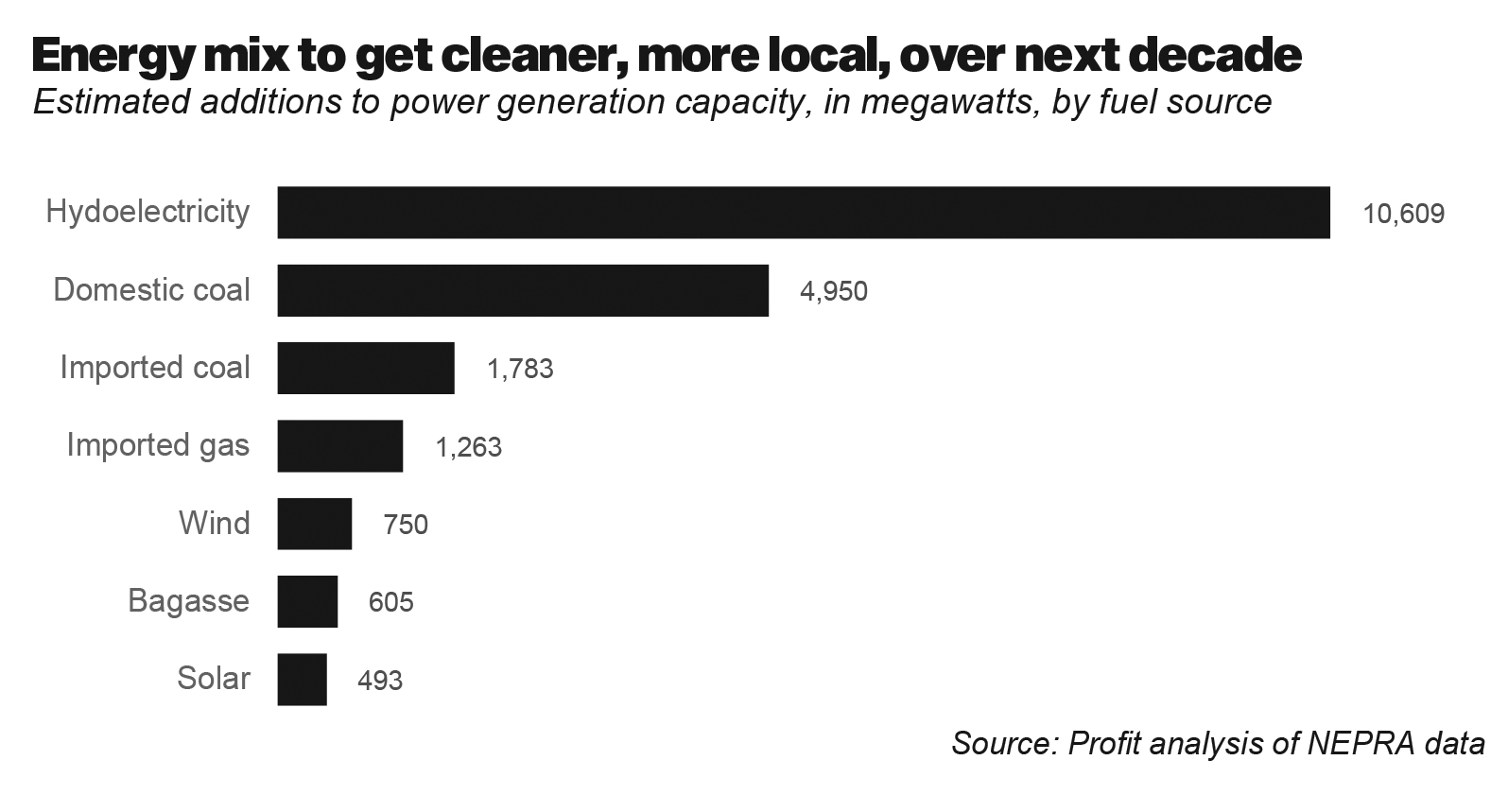

If the government can be patient and for once – just one energy price cycle – not panic and try to subsidise electricity unnecessarily, it will find itself with a problem that has fixed itself on the other side. Because a combination of the energy policies of the past four administrations means that the next decade will see an additional 20,453 MW of power generation capacity come online, in a mix that is both cleaner and less import-dependent than the current mix.

You see, the one good thing the PPP-led Zardari Administration did was to finalise a policy that allows for the construction of private sector hydroelectric power plants. The Nawaz and Imran Khan Administrations have started and continued the construction of the public sector Dasu Dam hydroelectric power project. And the Nawaz and Imran Administrations’ facilitation of the Thar Coal power projects means that that domestic source of energy will finally start to contribute a meaningful percentage of the nation’s electricity supply.

Of that 20,453 MW, over 10,600 MW are from hydroelectric power projects, the two biggest of which are the government’s Dasu Dam and the fifth extension of the Tarbela Dam. These two projects combined will add 5,730 MW in power generation capacity, with the bulk of that coming from the 4,320 MW Dasu Dam project. The remainder will come from smaller scale private sector hydroelectric power projects.

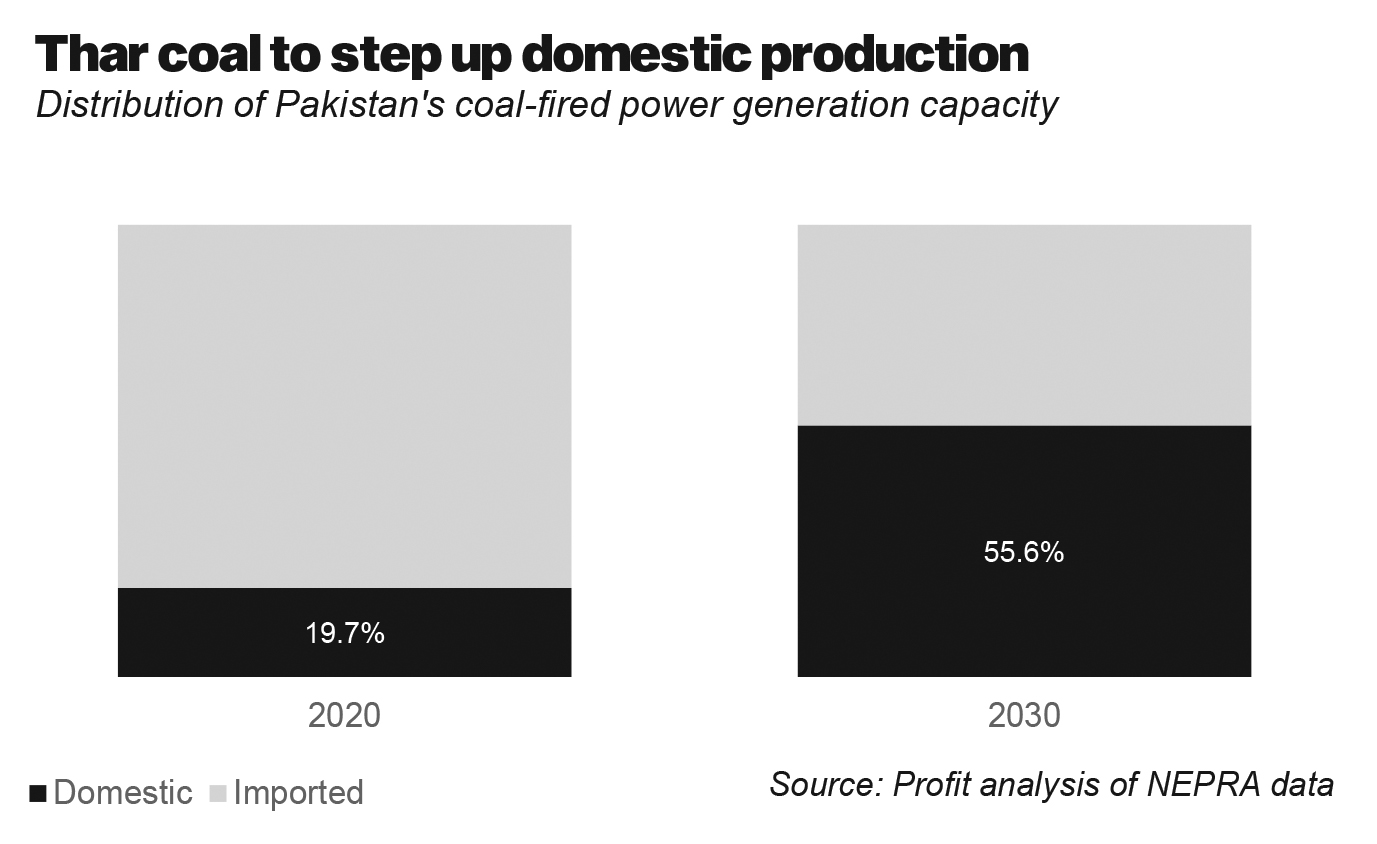

Nearly 5,000 MW of Thar coal-fired power projects will also come online over the next few years, which will change the make up of the country’s coal-fired power generation capacity. Currently, less than 20% of coal-fired power in Pakistan comes from domestic coal. Over the next decade, that number will rise to nearly 56% of coal-fired power generation capacity.

In short, if the government manages to not delay the construction of its hydroelectric power projects – and does nothing that will prevent the private sector hydroelectric and Thar coal projects from reaching completion – the country will see its dependence on imported fuels decline and the proportion of clean energy in its overall power generation capacity rise, despite the increased coal-fired power generation.

For that to happen, however, it is absolutely critical that the government not panic whenever global energy prices next start to rise. The prize here is a reduction in the country’s dependence on imported energy and for that to happen, the government will have to ensure that it does not sacrifice its long term ability to reduce the problem (construction of Dasu and Tarbela’s extension) for its short-term needs (decreasing the development budget to pay for increased subsidies on electricity).

Will that happen? Our initial inclination would be to say no. One can almost always count on the government of Pakistan to make the panicked, short-term decision. But then again, the government seems to have made at least enough of the kind of decisions to have placed itself on the verge of fixing a long-term problem.

So maybe there is hope they will not get distracted near the finish line? One can always dream.

Complete flop of a story from this CULT of a website. Calling other journalists “mouth breathers”, and claiming Pakistan needs to be “very, very lucky”.

They’re flaring gas in the Permian basin, shale gas is going to be sent around the world via lng terminals that are being built right now. Go look at the HH futures.

There will DEFINITELY be a glut of oil, many long term lng contracts are oil linked, it will be bad news for those thinking lng prices will rise dramatically.

Pakistans LNG deal with Qatar is around 10-14% of Brent.