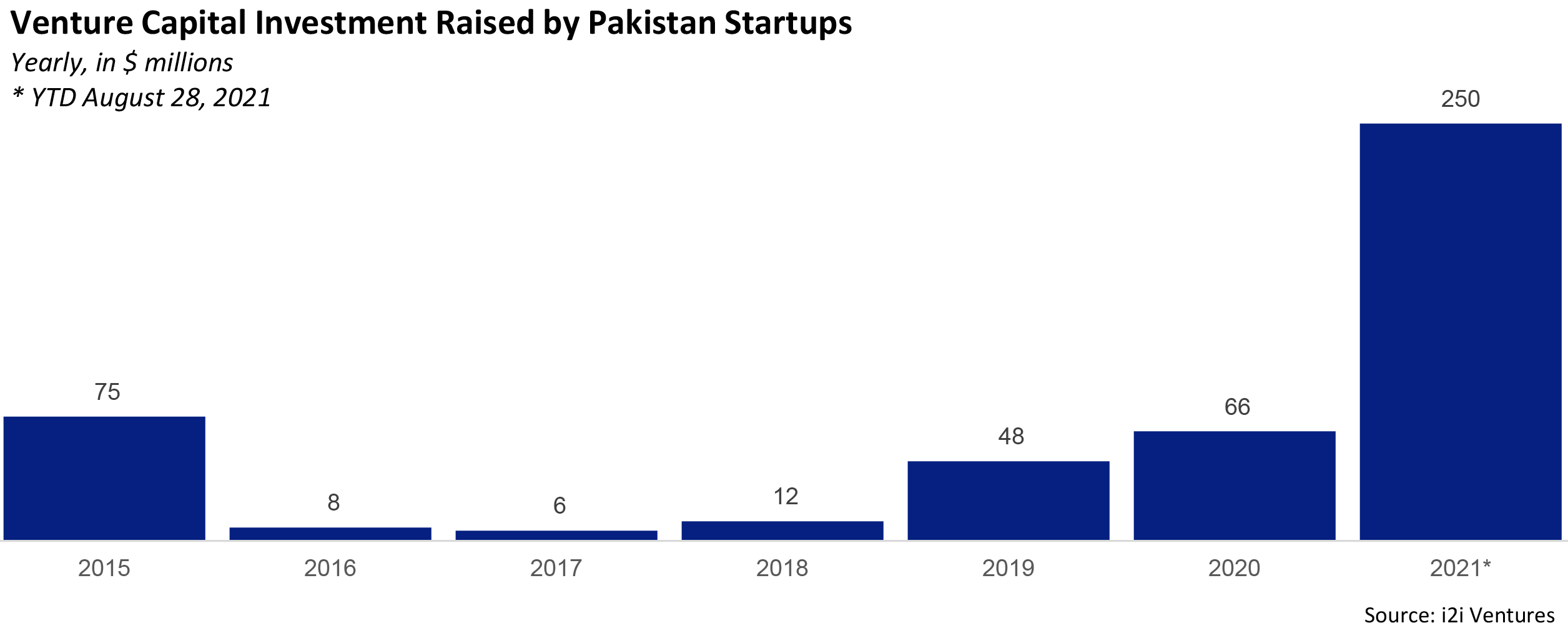

We could start by telling you all the superlatives, such as the fact that the largest Series A and Series B in Pakistani history (Bazaar’s $30 million and Airlift’s $85 million respectively) were announced in the same week and put together were more than total startup funding raised by all startups in the country over the previous three years combined.

We could tell you that this is a fantastic thing for Pakistani startups, and that the country’s economy is better off for having all the attention from foreign investors. We could list all of those foreign investors and tell you why each one is significant. We could even write a piece telling you why these investors should have been paying attention to Pakistan all along.

But those are all obvious takes and you have no doubt read countless of them already, including in the breathless tweets that quote-tweeted these announcements (including one from this author… guilty as charged) on Twitter.

Instead, we will focus on a layer below: why is this happening, what it will mean in terms of financing and business strategy for Pakistani startups and, crucially, what could potentially go wrong and how to avoid the more obvious pitfalls.

Why are foreign investors coming to Pakistan?

Let us start with the biggest and most obvious question: why is big money finally looking at Pakistan? As we see it, there are five key factors, one of which we classify as a push-factor, and the other four are pull factors.

- Exit from China: the push factor

Sure, there are some factors that are pulling investors towards Pakistan, and we will discuss those momentarily, but perhaps some of the biggest factors might be push factors: investors are coming to Pakistan because they cannot go elsewhere.

Specifically, they cannot go to China as much anymore. As the government in China starts cracking down on companies that have extensive ties with the United States and generally makes life difficult for foreign investors in the country, US venture capital investors have been seeing their opportunities to invest into China dry up.

And the speed and scale of the regulatory crackdown have stunned investors. In 2018, $17.4 billion of US venture capital dollars went into China, or about 14% of the total $122 billion in VC funding raised by US startups that year. Just two years later, that flow has fallen a staggering 86% to just over $2.5 billion in US venture capital investments into China in 2020. And the year 2021 is not off to a great start either.

All of that US venture capital money that was allocated towards China has to flow somewhere. And while some will no doubt remain in the United States, the vast majority of it will flow out of the US to emerging and frontier economies. Pakistan, like many other geographies, is at least partially just a passive beneficiary of that push-factor: China does not want US VC money, so US VC money is flying around the world in search of profitable investments.

- Pakistan is an attractive market, and better connected than ever before

Of course, there is certainly a pull factor for Pakistan as well. It is among the 10 largest countries in the world by population and finally has a substantial portion of its adult population now connected to the internet for the first time, and thus able to access internet and software-based services, the kind that attract the bulk of venture investing dollars.

- The domestic VCs

Pakistan also has a domestic venture capital industry now – albeit a small one – that speaks the language of global technology investors and can serve as local guides to foreign investors looking to establish a toe-hold into the country’s startup ecosystem. And while the Pakistani diaspora in Silicon Valley is dwarfed by the ones from India and China, it does tend to punch above its weight by sheer numbers, with a number of prominent venture capital funds in the United States having partners and senior investment professionals of Pakistani origin, who have not been shy about deploying capital into the country.

- Pakistan’s Silicon Valley expats

For example, Mikal Khoso of Wavemaker Partners led their investment into the B2B marketplace Bazaar. Mamoon Hamid led the investment for Kleiner Perkins into Bazaar’s rival Tajir. And Immad Akhund, a prominent entrepreneur and angel investor personally invested in the pre-seed round for neo-bank startup TAG.

- The Careem mafia’s Pakistan contingent

And then, of course, there is the Careem factor: the most prominent venture-backed exit in the entire Middle East and North Africa region is Uber’s $3 billion acquisition of Careem, which has led Careem to become for the region what PayPal became for the US tech startup ecosystem in the early 2000s: a font of tech talent and experienced operators who have the credibility to raise capital from global VCs comforted by the brand name on those founders’ resumes.

It is not just Founder-CEO Mudassir Sheikha: a substantial portion of Careem’s employee and executive base in many of its markets even outside of Pakistan is Pakistani, meaning a substantial portion of those Careem-mafia-chasing VC dollars will flow to Pakistani founders, many of whom are focused on the Pakistani market. Perhaps the most prominent of these is Saad Jangda, one of the two cofounders of Bazaar, which has raised $38 million in VC funding in the 15 months it has existed, including a $30 million Series A, the largest ever for a Pakistani startup yet.

Where will the money go? Blitzscaling

So what do you do as a startup founder when you get lots and lots of money from investors? You could invest a significant portion of it on hiring software developers, product managers, and designers to build out better versions of your product, and you probably will. You could hire marketing, customer service, and other support staff to help grow your operations and make them sustainable, and that is also certainly something a well-funded startup will do. It will also pay its founders a reasonable salary, spend on good office space, and a whole host of other benefits to make working at the start-up feel like it has the best of what a large company has to offer.

But mostly, you will probably spend money on blitzscaling.

Blitzscaling – which is a portmanteau coined by LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman, derived from the German “blitz” for lightning – includes all of the other elements described above. But, to crudely simplify, its core objective is to spend money to get users to come onto whatever platform the tech startup is building and to do so largely by spending money on incentives that make it attractive for users to stay on the platform.

So, for instance, think of the deals and low fares Careem offers riders, or the high compensation it offers drivers. The whole point is to try to get drivers to keep driving their cars for Careem and for riders to keep using Careem until both sides get so used to using Careem – and the service becomes so efficient – that the promotional rates can be taken away on both ends and the system would keep working.

Without asking any executive at Airlift, we can hazard an educated guess that the overwhelming bulk of the $85 million raised by the company will be spent on incentives for drivers and subsidised prices for customers. The goal will be to get more and more people to start using Airlift’s services as well as to retain existing customers.

The logic behind blitzscaling is the following: if the value of a business is based on the number of paying customers it has, and there is a certain cost to acquiring those customers, ceteris paribus, a company’s founders and investors will earn a higher return on their investment if those customers are acquired faster rather than slower. Building a platform faster also reduces the risks of competitors building similar or better products and taking away market share.

Let us illustrate this with a specific example. In a story published in February 2021, Profit laid out estimates for Careem Pakistan’s customer acquisition costs (CAC) and average revenue per user (ARPU). We showed that, by the end of year 3, Careem had over 3.1 million users, which resulted in net revenue for Careem (after paying the captain’s share) of $9.6 per user per year.

Careem spent $117 million acquiring those 3.1 million users. What return did Careem’s investors earn during those three years? For simplicity’s sake, let us assume that 40% of Careem Pakistan is owned by employees and the remaining 60% by investors.

At the end of year 3, Careem was earning about $30 million in net revenue. Applying a valuation multiple of 10 times revenue (not uncommon for a fast-growing tech startup), we arrive at a valuation of $300 million. Using the simplifying assumptions above, Careem’s investors would have an internal rate of return (IRR, a measure of investment returns that takes into account timing of cash flows) of 32% per year.

Now, suppose instead of investing that $117 million over three years, they invested it over two years. What would that do to the IRR? It would go up to 51% per year. (Do not try to replicate these numbers. We used Careem Pakistan’s actual cash flow numbers and applied our modifications to those numbers, so this math would be impossible to replicate without that data in front of you.)

Obviously, if you can pull up the growth, it makes a lot of sense to do so, even if it means investing a larger amount of cash up front. That, in a nutshell, is one of the biggest advantages of blitzscaling. It is particularly relevant for companies that expect to take several years to hit the point of cash-flow breakeven, let alone generate enough capital to internally finance their own growth.

Incidentally, one of the key people in charge of implementing Reid Hoffman’s blitzscaling ideas at LinkedIn? Aatif Awan, the founding partner at Indus Valley Capital, one of the major local venture capital funds in Pakistan, and a backer of both of the two record-holders of the largest Series A and Series B fundraising rounds for Pakistan. Before founding Indus Valley Capital, Awan was VP of Growth at LinkedIn.

The limits of blitzscaling in frontier markets like Pakistan

You will notice one big underlying assumption behind the concept of blitzscaling: that the users are there to be acquired and that the CAC will not be disproportionately increased by compressing it into a shorter timeline. This assumption holds true in many market segments, even in Pakistan… but up to a point.

And when committing to a blitzscaling strategy, it is absolutely critical that a startup founder have at least a rough idea of when that point would be reached. Because the investors will not know. Only the person actually in the business will have the ability to know the answer to that question, and the answer to that question determines how much money is appropriate to raise.

We do want to emphasise: precision is not important, but accuracy is. So, for example, it is okay for a startup to think their market is 10 million people and it turns out their market was only 6 million people. It is not, however, okay if they thought their target market was 100 million people and it was still just that 6 million people.

How does one determine how big a market one has? Think about every single characteristic that a person needs to have in order to be a customer and user of the company’s product or service, and then obtain as close to reasonably accurate estimates as possible of the proportion of the total population that meets all of the minimum characteristics needed to be a user.

In Pakistan, the two challenges startups frequently run into are income and infrastructure. So, for example, for Careem, the minimum requisite characteristics of a customer include ability to read English, own and operate a smartphone, have mobile broadband internet, and have enough disposable income to be able to afford a Careem ride on at least a monthly basis, but not have enough income to own a car available for exclusive personal use.

It turns out that once you filter for all of those characteristics, of the 220 million people who live in Pakistan, the total number who fit that profile is just over 3.1 million. How do we know that? Because Careem’s cost of customer acquisition skyrocketed when it tried to grow beyond 3.1 million users. Careem acquired its first 1.4 million customers for about $34 per monthly active user, the next 1.7 million customers for about $38 per monthly active user. The next 0.5 million customers? They came at an average price tag of $122 per monthly active user.

If, after the first million users, Careem had raised money assuming they would have 20 million monthly active users, they would have been in big trouble if they had tried to raise it all in a short amount of time. Luckily, they did it somewhat slower, which allowed them to gauge just how much money they needed to raise without asking for too much money and then suffer the ignominy of disappointing expectations.

For Airlift, having the example of Careem before it gives them a fairly good sense of just how much they might need to spend in order to achieve scale. For Bazaar and Tajir, the task of determining just how much money they need is a bit harder, but the risk is lower: much of their capital is likely going into inventory that will likely be sold at some point, even if not as fast as they are hoping.

But what these examples show is this: startup founders need to have a clear sense of who their customer is so that they can have a reasonably good guess as to how much money they will need. For example, a neobanking startup needs to understand that the vast majority of its customer base will already have existing bank accounts, but will exclude people who are high earners and thus want to transact in large volumes, which are currently prohibited by the State Bank of Pakistan.

So, sure, there are about 20 million people with bank accounts in Pakistan, but a neobank’s prospective customer base is a much smaller subset of that, and a less lucrative one at that (since the most profitable customers are the richer ones who have large balances in their current accounts).

If a startup gets these estimates badly wrong (a little wrong is okay), they run the risk of encountering what can be the kiss of death for a business that has been raising large sums of capital: a down-round, which decimates their ability to keep raising money to grow.

The expectations problem, and what to do about it

A down round is when the valuation of a startup in a particular fundraising round is lower than it was in the previous fundraising round, resulting in its previous investors suffering losses. If previous investors suffered losses, prospective future investors will start to shun the startup, severely limiting its ability to keep on raising money, which – for a business that has grown accustomed to paying for rapid growth – can be the death knell.

This is going to be particularly important for Pakistan, considering the fact that foreign venture capital investors are getting their first taste of the market, and have never been through a Pakistani market downturn. Indeed, most of these investors have never even been through an emerging and frontier markets downturn in venture capital. The industry is simply too new for that to even have happened yet.

And historically, if public equity markets investors are a reasonable precedent to go by, Pakistan tends to get penalized more heavily for market downturns – in the form of panic sells – than other similar economies. The nature of venture capital makes panic-selling somewhat less likely. But one can expect future inflows to completely dry up if investors completely get spooked.

And that is before we even get into the prospect of fraud or other deception by Pakistani startups, which would be a body blow to the ecosystem regardless of what phase of the investing cycle the market was in.

One way to avoid the problem for the Pakistani startup ecosystem? For founders to not get too greedy when fundraising, and appraising the offers of investment not on the basis of the highest available amount, but the one closest to the startup’s needs. That will require holding venture capitalists to a fiduciary standard with respect to their own investors, as well as the startup founders.

What does that mean? It means they need to be incentivised to act in a manner that maximises the returns for investors, regardless of whether or not that has an adverse impact on the revenue line for the venture capital firm itself. One might assume that, considering the fact that the vast majority of a VC fund’s revenue comes from successfully closing out all investments at huge profits, that the incentives of investors and VCs would be completely aligned.

And while it is true that there is general alignment, there can at times be a conflict of interests, particularly when the VC is trying to raise more funds on the back of being able to show good paper returns on existing investments. Raising more money for an existing fund, or for a new fund entirely, can result in a new revenue stream for the VC managers that is independent of – and sometimes conflicts with – the interests of its existing investors.

See, to raise new funds, the VC needs to show their existing investments are doing well, which means having the ability to mark up the value of those investments. In illiquid investments such as venture capital, the only time a markup comes along is when another round of funding is executed, which gives a VC who is in fundraising mode for their current or new fund an incentive to seek larger rounds at a higher valuation. But higher valuations mean higher expectations, and a higher possibility of disappointing those expectations for the founder, and raising the danger of losing control of the company or even outright failure.

Hence why VCs need to act as fiduciaries to their existing investors: acting in their best interests, even if it does not completely align with the financial interest of the VC themselves.

It is a tricky business, knowing how much you need, and having the strength of conviction to turn down more money than one expected. But for their own long-term financial interests, and for the interests of Pakistan’s startup ecosystem, Pakistani tech founders need to resist the urge to go for the biggest cheque sizes if it is the wrong number, regardless of who is calling and how much they are offering.

Greed, in this case, is not good at all.

Amazing article. Helped me made sense of whats going on.