The hardest, most profitable thing to do in the business world is to get ordinary people to change their behaviour. Doing so in a low-trust society like Pakistan is harder still. And convincing other people to give you the money to do that hardest of hard things in business, well… you would have to be at least slightly insane to try that. The team at Careem, however, have managed – largely – to pull off all three, and done so very successfully.

Yes, we know. Careem is technically a regional startup based in Dubai, but Pakistan is clearly an important part of their story, and for the purposes of this analysis, we at Profit will be focusing on their Pakistan operations.

Before going any further, we would like to clarify one thing: this is not another “how they built it” story about Careem. That story has been told, including in this magazine, and while fascinating, at this point is not new. Instead, this is an analysis – using financial and operational data from Careem’s Pakistan operations – to understand exactly what it took for Careem to induce the change in behaviour needed for their business to succeed (including estimates of actual amounts spent), and whether that bargain was successful.

We do this to illustrate a simple point: building a business that relies on an entire population that is still new to technology to start using your service off their mobile phones is hard – and expensive – but ultimately worth it.

The relationship between CAC, ARPU, and LTV

Before we dive into our analysis, it would be helpful to lay out some concepts that, while intuitive, are nonetheless useful in understanding the viability of a business. They are customer acquisition costs (CAC), average revenue per user (ARPU), and lifetime value of a customer (LTV).

The customer acquisition cost is the marketing costs, broadly defined (advertising, but also costs of promotional giveaways, etc.), divided by the number of customers the company is able to add. The average revenue per user is usually a per year or per month number (in this analysis, we will use per-year data). And the LTV represents the ARPU multiplied by the number of years a customer is expected to remain a customer.

The biggest problem with many consumer-facing technology companies is that they are able to use heavy promotions and absurdly discounted prices to lure customers in the door, but then are not able to keep them there, usually because it becomes unviable to keep up the discounted prices and too many customers simply leave once the low prices end.

The successful ones are able to keep customers around either by developing hard-to-shake habits, or because customers fall in love with the product, or because they went after the right customers who only needed the promotional pricing to try the product and once they did, they were comfortable paying full price.

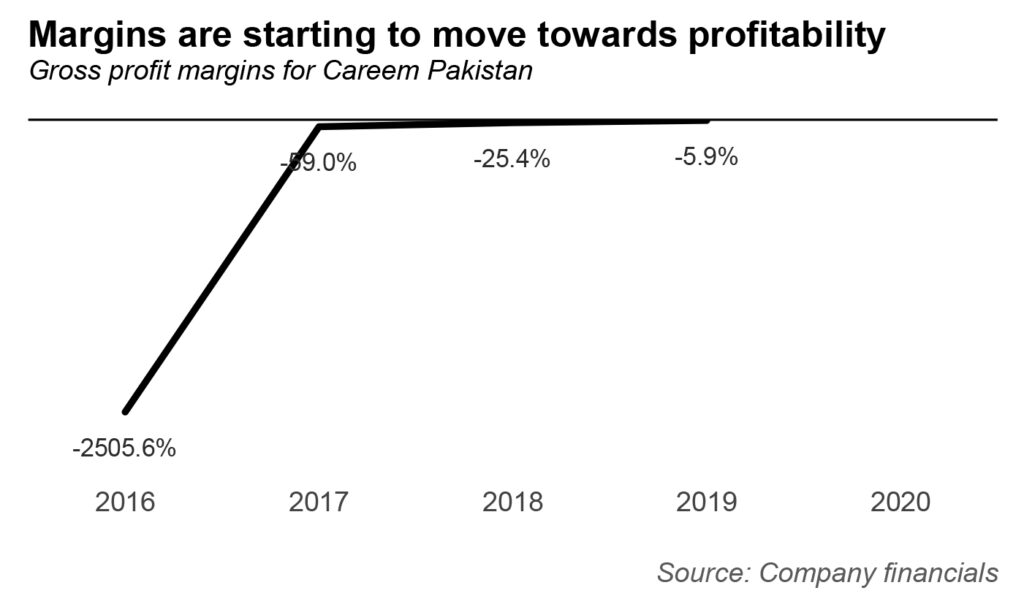

For a business to be viable, its CAC needs to be lower than its LTV or else it will never make money. For it to become profitable, its CAC needs to go lower than its ARPU before its investors lose patience and stop giving it the money to keep going. To put this in accounting terms, if a company’s gross margins become positive, at some point, it can be assumed that it will achieve the scale it needs to become profitable. This is why venture investors tend to pay attention to unit economics more than the bottom line.

The big concern investors have in a market like Pakistan is that the ARPU takes too long to exceed CAC and thus significantly reduces investor returns and increases the likelihood of business failure.

As we will see in the case of Careem, however, there is evidence that it is certainly possible to have CAC and ARPU converge, even for a market where one has to invest heavily to gain an adequate customer base.

A note on methodology (feel free to skip)

For this analysis, we rely on data from Careem’s financial statements from 2016 through 2019. We were not able to obtain the 2020 financial statements and the company declined to share revenue data for the year, though they did share some interesting operational data, some of which we have previously reported on already.

That detailed financial data allows us to examine how much the company bills customers, how much it pays out to drivers, and how much it spends on different types of promotional expenses (how much given in bonuses to drivers, and how much in credits, etc. to riders, for example). That gave us the amount it spends in total on customer acquisition.

In order to calculate CAC and ARPU, however, we need to have the total number of active users for each year. Careem’s financial statements do not include that data, and their management declined to share historical data on the number of active users.

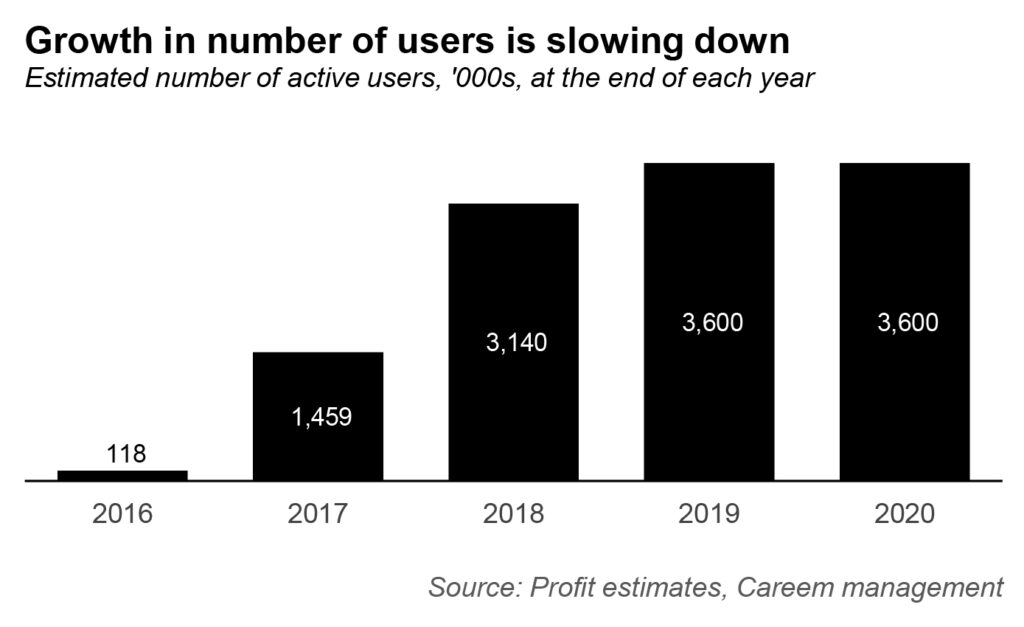

Careem’s management did, however, share that they currently have 3.6 million active users on their platform, and approximately 200,000 active drivers. For our analysis, Profit assumed that the number of active users did not materially change during 2020 and that the number at the end of 2019 was effectively quite similar.

We then used some operational data that Careem had shared on the average fares from 2016 through 2020 to calculate the total number of rides by year, divided the number of rides by the number of users for 2019, and then made a simplifying assumption that the number of rides per user did not change in previous years to calculate the number of active users at the end of each year. We also assumed that non-ride-hailing revenue was negligible from 2016 through 2019.

Once we had those numbers, we could easily calculate how many users, on net, Careem gained in each year, which allowed us to use the financial data from its financial statements to calculate approximations of their CAC and ARPU. These numbers, we cannot emphasise enough, are Profit’s estimates and not actual data from Careem. We think we are close, but we are not 100% accurate in our estimates.

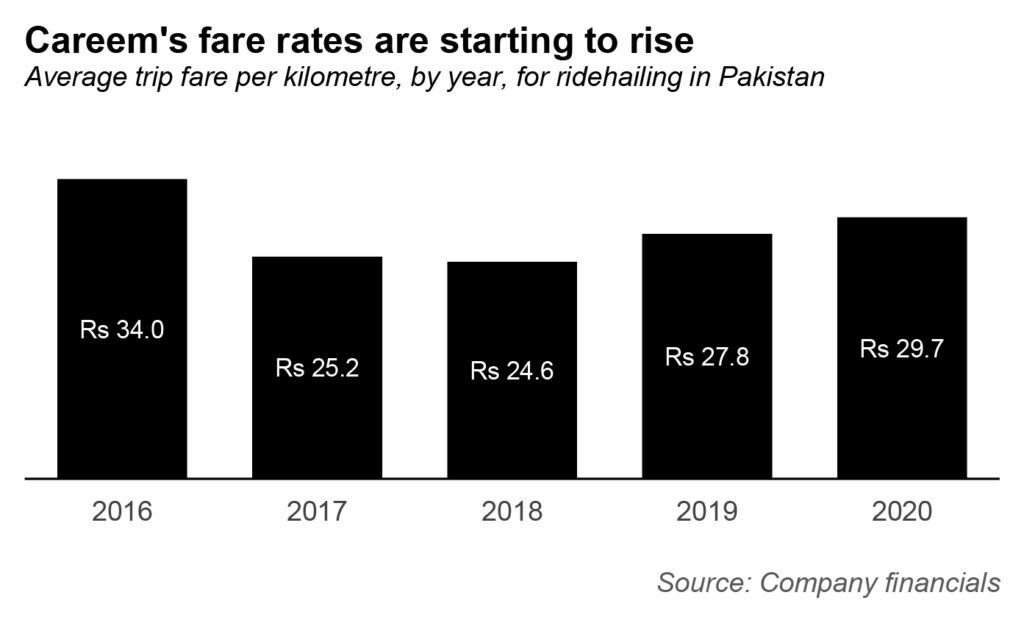

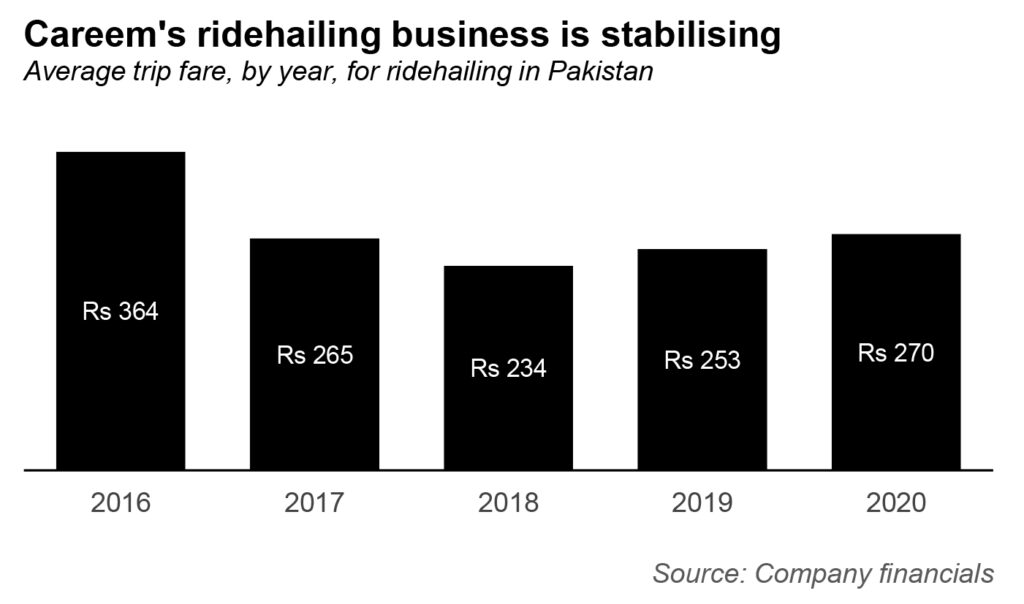

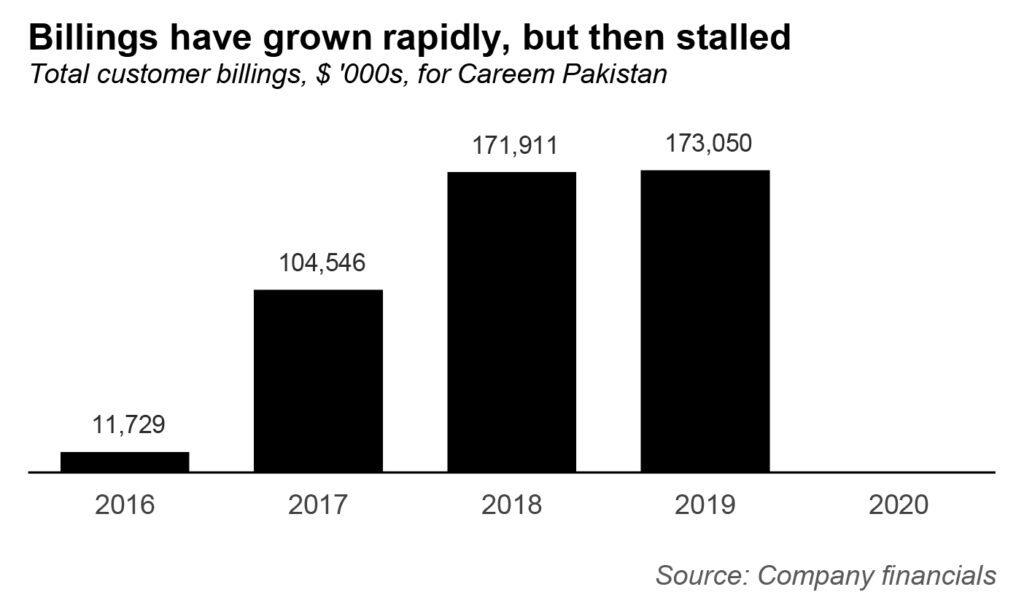

Careem’s narrowing losses

The first thing that is evident from the data is that Careem’s customer billings (not the same as its revenue) skyrocketed between 2016 and 2018, but then stalled somewhat in 2019. Part of that is due to the fact that we are presenting this data in US dollars. In Pakistani rupees, Careem’s revenue actually grew by 24% to Rs25.9 billion, but that rupee growth was almost entirely wiped away in US dollars by the depreciation of the rupee against the dollar.

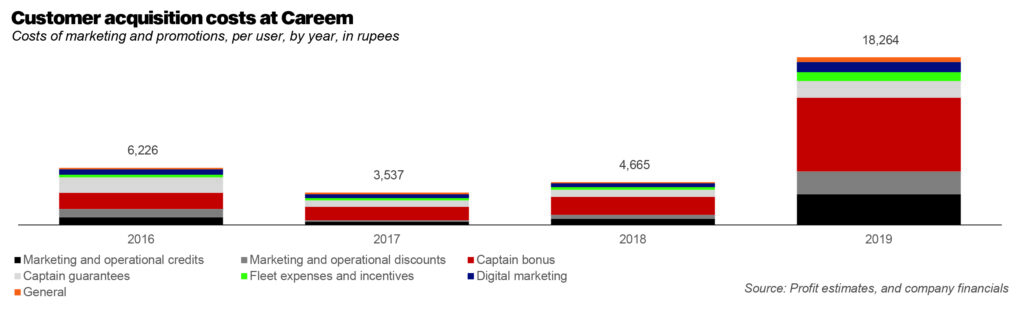

And Careem’s CAC does not have an obvious pattern: it starts off high in 2016, declines by almost half in 2017, rises somewhat in 2018, and then suddenly skyrockets again in 2019.

So, what is happening with this business?

When Careem started out building its network, it faced a chicken and egg problem: if it did not have drivers and cars, no riders would want to use the app. But if it did not have riders, no drivers and cars would want to join its network either. Each would need the other to be there to make it worth their while, but neither would start unless the other was already there.

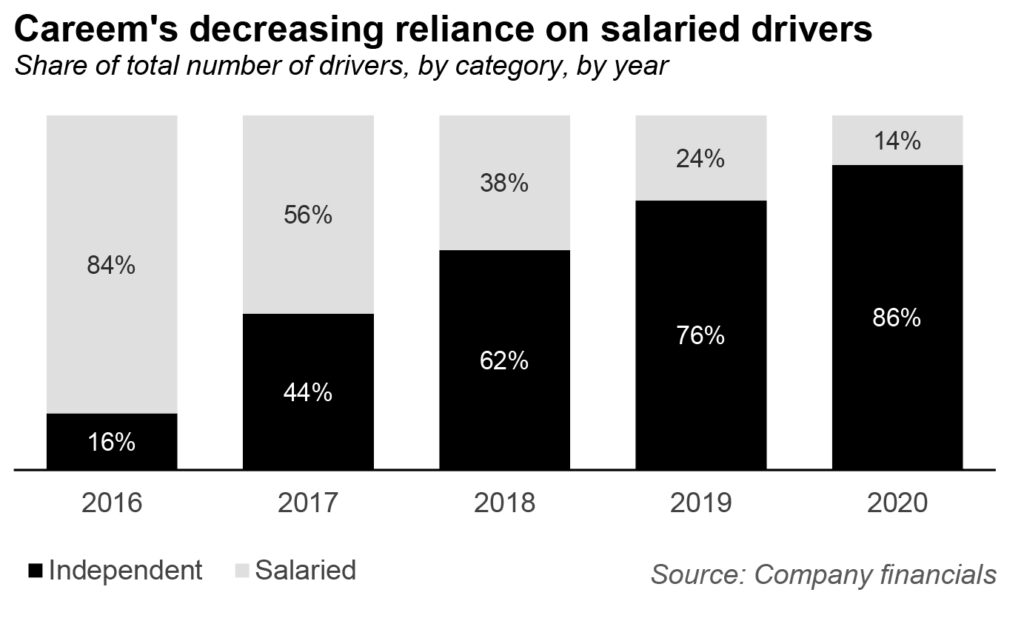

Careem solved this problem – as every ride-hailing company does – by incentivizing the drivers to be available, no matter whether or not they had riders.

“All startups initially spend lots of money to acquire stakeholders,” said Zeeshan Hasib Baig, CEO of Careem Pakistan, in an interview with Profit. “We did too. Initially, we had to provide captains [what Careem calls its drivers] monthly income and other incentives.”

“During the initial phase of our entry in the market, we used to offer a certain captain guarantee on the ride-hailing front to create the supply needed to fulfill the demand of the customers. Since the demand on the platform initially was not enough to make a decent ROI [return on investment] for a captain, Careem funded it in-form of incentives and bonuses, as the demand and user base increased these incentives naturally reduced and the earnings were ensured by higher demand in the form of more rides for captains,” said Baig.

Those incentives did not come cheap. Between 2016 and 2019, Careem spent a total of Rs12.5 billion in incentives to drivers, over and above the Rs43.7 billion they were paid in their share of customer fares over the course of those four years. These numbers exclude the amount of money Careem paid to incentivize people who own fleets of cars with employed drivers to have them join the Careem network.

In 2016, about 29% of the income that captains derived from Careem was from bonuses and guarantees alone. As the business has grown, that number has declined to about 19% in 2019. “As our customer base grew, we no longer need to [offer such incentives]. We do not have to pay captains from our own pockets anymore,” said Baig.

Driver incentives form the core of Careem’s customer acquisition costs. About two-thirds of its CAC goes in the form of direct payments and bonuses to drivers and fleet owners, with about a quarter going to riders as credits and other incentives, and the remainder on digital and other marketing expenses. So, when Careem says they value their captains, their financial statements back up that assertion.

“Captains are at the heart of what we do and a priority area for us since we started services; to put it simply they are an integral part of the Careem family. Careem has always been at the forefront of coming up with initiatives designed at improving the quality of lives for captains,” said Baig.

Over the past four years for which Profit was able to obtain data, the captains made about 72% of the total amount of money spent by Careem, a number that has remained remarkably consistent during that time, though much more of it now comes in the form of their share of the customer fares than the Careem bonuses and incentives than it used to.

So, if CAC consists largely of the incentives to captains, and the amount Careem has to spend as a share of its business on those incentives is going down, then why has the CAC number fluctuated so much? Because the actual costs are just the numerator. The denominator, which is the net growth in the number of users, has been more volatile.

The hard task of growing the user base

By Profit’s estimates, Careem has done a remarkable job in growing its user base. During 2016, its first full year of operations in Pakistan, the company had approximately 118,000 active users, according to Profit’s estimates using the company’s financial and operational data. By 2020, that number has grown to 3.6 million, a remarkable feat by any stretch of the imagination.

That growth, however, has not come at a consistent pace, with most of the riders joining the platform within the first three years, and relatively slower growth since then. So if the company is spending the same amount of money to acquire users, and fewer new users join, the CAC would go up.

Let us break down what happened. When Careem started its services in Pakistan, it was mainly in the major cities of Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad, and initially only in the upper middle class neighbourhoods of those cities. These are Pakistan’s most urbane, sophisticated consumers, most of whom had smartphones before there was 3G internet in the country and had considerable discretionary spending ability.

To attract such users, Careem basically had to spend money to get them to try the service, but once they tried it, they were likely to stick with it and mention it in casual conversation with their friends who were perhaps not as early adopters of new technology. So when Careem’s advertising and marketing reached that next circle of people who were the friends and family of its early adopters, it did not need to spend nearly as much to convince them to join, resulting in a jump in the number of users without the marketing spending needing to rise by the same amount.

It also achieved a certain amount of economies of scale: if there were more riders, more of a driver’s active time was covered by a customer fare and did not have to be subsidized by a Careem bonus or incentive payment.

So, it makes sense that when it saw rapid growth in the first three years, its CAC declined. What happened next – when it hit approximately the 3 million user mark – is a sad commentary on Pakistan’s segregated political economy: the number of people who can afford Careem’s services (and need them) begins to dwindle past those 3 million people.

In 2019, Careem continued to offer the same level of incentives to its drivers and riders as in 2018, but its active user base – which had grown by 1.7 million people in 2018 – only grew by approximately 460,000, according to Profit’s estimates. The CAC then skyrocketed.

At that point, Careem – which did not yet have ARPU that was above its CAC – faced a choice: it could, to borrow American football parlance, either go wide or it could go deep. Going wider would mean going after more customers with the same service. Going deeper would mean going after its existing users with newer products and services that it could deliver and that they might like.

Careem’s management, while not using this explicit language, has made it abundantly clear that they choose to go deeper rather than wider.

To increase ARPU, raise the R, not the U

In 2020, even before the pandemic hit, Careem’s global management as well as the one in Pakistan was getting ready to launch their super app, which would begin to offer a wider array of services beyond just ride-hailing. Of course, the coronavirus pandemic then hit the global economy, with shut downs decimating any kind of travel and transportation business, including that of Careem.

The company’s management is shy about releasing data on their operations in 2020 and we do not blame them: the numbers will look bad, and will not in any way be reflective of the fundamentals of the business. They will serve mostly as noise that will distract from the ability to understand the direction it is taking as a company.

That said, however, the initiatives it launched in Pakistan – both the delivery business as well as Careem Pay – indicate that Careem is interested in gaining a higher share of wallet from its core base of about 3 million active users rather than converting more of its 11 million registered users into active ones.

That stands to reason: those 3 million people have more money to spend and they are spending it right now on services that Careem is well positioned to provide. It has a fleet of cars, motorcycles, and other vehicles, along with drivers, so expanding into delivery is a natural expansion.

“The opportunity for growth in deliveries and food business in the region is massive,” said Baig. “It is an unprecedented time, but Careem is well-positioned to pivot and simplify and improve the lives of our customers the best way we can.”

“We will continue to leverage our Super App to cross sell to users across different verticals by developing a stronger loyalty program as a differentiating factor which would offer additional value. We also look forward to expanding our food delivery business in major cities of Pakistan and offer a seamless delivery experience,” he said.

And, in a country with a still largely inadequate electronic payments mechanism, Careem has built the largest internet-based business in Pakistan, proving that it can get people to trust it with money over the internet, so why not expand its payments capabilities as well?

“The entire Super App infrastructure also requires a robust payments solution, which is extremely critical to the entire equation, since it not only encourages the over 90% cash-based transactions on the platform to go digital but also provides a range of financial services which fills a big gap in the entire region,” said Baig.

What is the risk?

It seems like a relatively straightforward proposition: Careem can continue to leverage its core assets to build a great platform that will allow it to increase revenues with relatively less investment in seeking to gain new users. What could possibly be the downside?

None, if executed well enough. But every major consumer-facing tech company thinks they can build a WeChat-like Super App and yet almost nobody else has succeeded in doing so yet, and for a reason. Offer too much in one app, and you risk overwhelming your customer with too much choice, and a cumbersome user experience where they are not able to conveniently access the services they most value, and so they may stop using your services entirely.

Adding delivery and payments may seem simple enough. But Careem’s plans go beyond that. “For next year, in some countries we are exploring to add innovative solutions to the Super App such as engaging with other businesses and startups to integrate their services on the Careem Super App through its open architecture,” said Baig. “This way they can benefit from our customer engagement and also benefit from the enabling services we have built, whereas our customers benefit from having more services at the same platform.”

Becoming a platform for other startups sounds like it may be a great idea, or it may just end up creating confusion for users and detracting from the core Careem experience. What direction it will take will depend entirely on the quality of its technology and product managers. No pressure, folks.