All you can see for miles and miles is the thick, green, garden acreage grown on hilly terraced fields. The tea-gardens of Mansehra, much like tea-gardens all around the world, seem almost ahistorical. As if the plantations have been a part of the landscape since antiquity. Yet the breath-taking sights of tea-gardens hide a grim past, and a squandered opportunity.

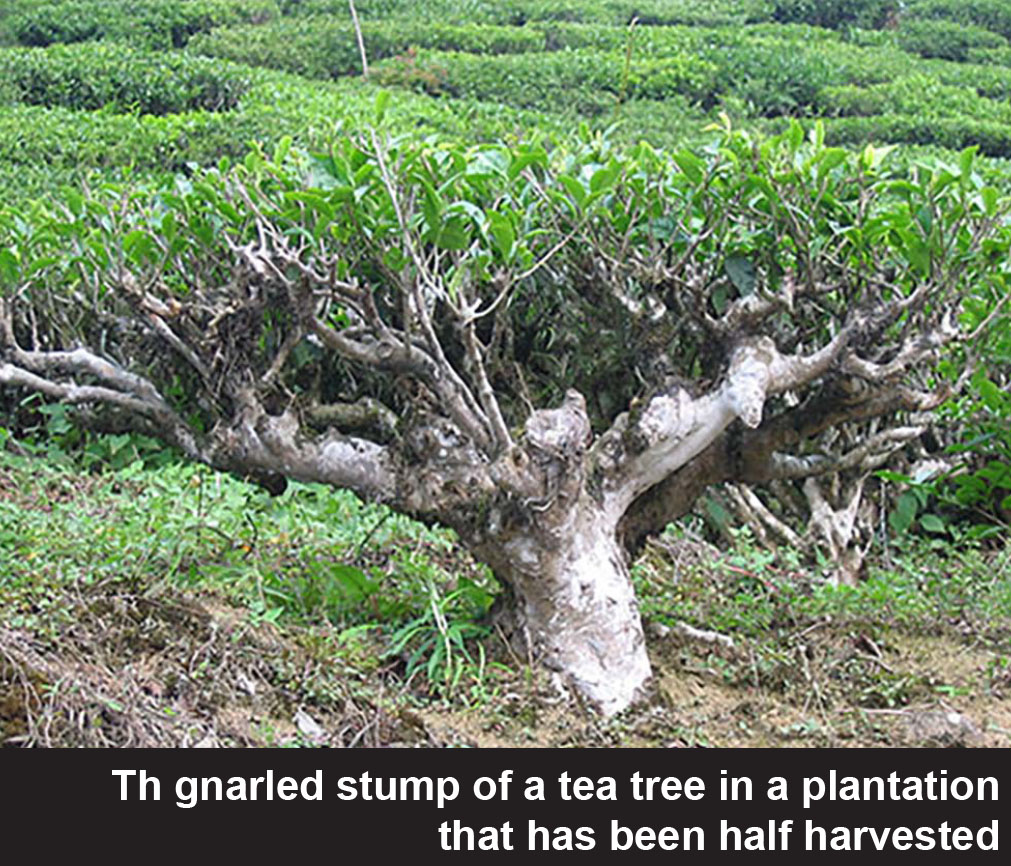

Tea is not sown in the ground and harvested each year. Underneath the charming green leaves that make up these fields are thick, gnarled, trunks. In their natural state, tea trees have been known to grow to heights of 50 to 70 feet. When planted in the fields so close together, they rarely reach over four feet, making tea-gardens a vast forest of miniature trees. The average tea tree needs to be at least three years old before its leaves can be harvested, and lives up to the age of 30 to 40. Every year between March to December, these dwarfish trees sprout leaves that are then harvested by men and women wearing straw baskets on their backs. At the height that they stand, it is back-breaking work.

Behind the development and cultivation of these gardens is a painful history. These fields are not an ahistorical part of the landscape as they seem. And while the regions where tea is grown often become synonymous with the gardens, such as Mansehra in Pakistan or Assam and Darjeeling in India, tea gardens emerged at a particular historical moment.

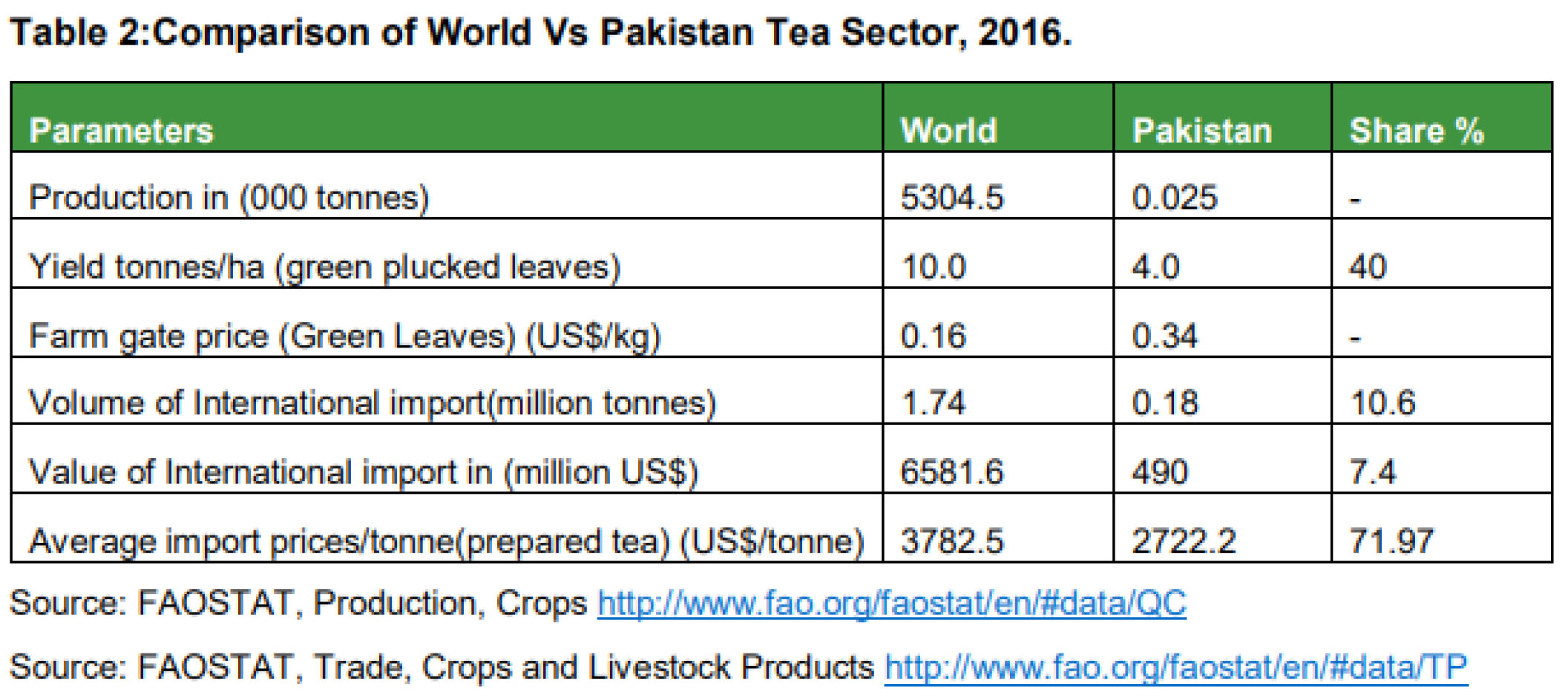

Today, as a result of that historical moment steeped in a legacy of colonial gluttony and hubris, India is the second largest producer of tea in the world with an output of 0.94 million tonnes produced out of 0.389 million hectares (ha). Of the massive amounts of tea it produces, India consumes 70% of its tea itself. In comparison, according to a report of the Planning Commission, tea is cultivated at an area of about 100 ha only in promontories of District Mansehra under Unilever Brothers Support with production of about five tonnes. Yet Pakistan is also the world’s largest importer of tea, spending Rs 90 billion every year to import tea, with Rs 89 billion spent on black tea and Rs 1 billion on green tea. Could we be growing more, and more importantly, should we?

A question of fate

As beautiful and eternal as they may seem, the tea-gardens of Mansehra are a relatively new set-up. Its origins go back to 1982, when a feasibility report was prepared by a team of Chinese experts, which declared more than 64000 ha land suitable for the desired purpose. This study found a number of areas suitable for tea cultivation, including some parts of Swat and Azad Kashmir. But the star of the study was the hilly terrain of Mansehra. It was after this that a government backed tea-growing initiative was launched in the district.

While these may be the origins of tea growing in Mansehra, the seeds for this were sown even earlier. In a speech delivered to the Indian Tea Association in London, Arnold Whittaker explained how tea had originated in China in the ninth century, where over the centuries an impressive volume of literature on the growth of the plant and the technique of tea drinking had been written. However, as he explained in his speech, the dominance of the China tea industry had two unfortunate effects on the development in India. The first and more important of the two is the fact that the East India Company had the monopoly of the tea trade with China which caused the company to discourage any tea venture in India.

However, in 1813, parliament curtailed the company’s powers and started playing a more direct role in the administration of British interests in India. In 1834 Lord William Bentinck, who had been appointed Governor-General in 1827, appointed a committee to submit “a plan for the accomplishment of the introduction of tea culture into India and for the superintendence of its execution.This was just a few decades before the British would overthrow the 1857 War of Independence and annex India under crown rule. By the time this happened, the British realised that they had more direct control in India than in China and the growth of tea in the subcontinent grew exponentially so that the demand for the warm drink could be met back on the island.

Now, tea was already grown in India on a small scale by the time the British started. Whittaker in his speech mentions how “as early as 1815 a British officer named Colonel Latter had reported that certain of the hill tribes in North-East Assam made a drink from wild tea growing in the hills. In 1823 Major Robert Bruce took a trading expedition to Sibsagar and found wild tea, and in 1825 this Society of Arts offered a gold medal – or fifty guineas – “to the person who shall grow and prepare 20 lb. of good quality.”

In the years that followed, the British were determined and empowered. Assam was the first area to be developed, and was followed by planting in the Himalayan foothills in 1842, in the Surma valley in 1856, in Darjeeling during the next two years, and by 1874 in the Western Dooars. In South India commercial planting had begun in 1853, but development was slow here and nearly two-thirds of the total acreage under tea was planted after 1900. By 1949, two years after partition and at the time Whittaker gave his speech, India was producing a total crop of 600 million pounds annually, nearly half of which was being exported to England.

The rapid rise of India as a tea-growing country was a testament to the ingenuity and grit of the British colonists. However, they managed to achieve this at a great cost to local communities. According to Anirban Bhattarcharya, the formal abolition of slavery in the west was neatly replaced with the rise of plantation empires in the colonial peripheries of India, Ceylon, Malaysia, Sumatra and so on. “Entire plantation societies or plantocracies mushroomed in these areas, all more or less in the same period; spanning the latter half of the nineteenth century and becoming an inseparable part of colonial economies by the turn of the century,” he writes.

The British approached the project with a vicious dedication. As early as 1840, ‘wastelands’ or ‘virgin lands’, were handed over ‘revenue-free’ to planters for tea in Assam, Darjeeling and eventually in the Duars. Yet the racist and belittling ideology behind the colonial project was apparent. Wasteland rules in Assam were made and amended with the express purpose of encouraging foreign enterprise (read planters) to lease vast tracts of wasteland on exceptionally liberal terms. For instance, a clause was incorporated in the rules of 1838 to the effect that no grant was to be made of a lesser extent than a 100 acres. The objective behind fixing such a high minimum ‘was to keep off indigenous claimants.’ In fact the minimum eventually was raised from 100 to 500 acres. And as was desired, these concessions did lead to the utilisation of large tracts of land for the purposes of plantations.

There are tales of British ingenuity that made this transformation possible, but it was all tied to and propelled by the needs of the emerging tea industry. “Transformations in this region, for instance, involved its forests and its grazing lands – resources upon which depended the lives, customs and livelihood of the local population, particularly the indigenous tribes. Forest rights and grazing rights were especially affected which were bound to have far reaching implications for the region and its landscape. Ultimately they were in direct contravention of the subsistence needs of the local populace,” writes Bhattarcharya.

Pakistan’s tea

Over the course of a century, from the 1850s all the way down to partition, tea thrived in India. It became a major source to send back home from the empire, and it also quickly became a popular drink in the subcontinent. While it was grown largely in Assam and other hilly areas as well as in South India, most tea plantations remained largely in what would be India after partition, with Pakistan getting none of the major tea plantations.

However, a taste for tea had already been acquired in the areas that would become Pakistan, and that meant the new state would have to import tea from either India or Sri Lanka to make up for its demand. One of the many gifts of the partition was that there was suddenly a country with a very large appetite for tea but no capacity to grow tea. One of the major companies operating the tea business in Pakistan at the time was Lipton, owned by Unilever and Brooke Bond, another British tea company. The first major local tea company to start off in Pakistan was Tapal, which came to life shortly after Partition in Jodia Bazar in Karachi, where the Tapal family began their tea business: Importing tea from Sri Lanka and then selling it wholesale in the markets in Karachi. Jodia Bazar is, to this day, one of the largest wholesale markets in Pakistan. It helps that it is located just a few miles from Karachi Port and is located in the city that has the single largest concentration of the Pakistani urban middle class.

The hunger for tea was big in Pakistan. The store in Jodia Bazar soon grew as Karachi went from being a relatively minor city in British India to becoming the largest city in Pakistan. The tea business outgrew the store and began marketing itself far beyond the retailers and occasional consumer buyers who would come to the store. Tapal grew because the demand for tea grew, however the entire tea business in Pakistan was dependent completely on imports.

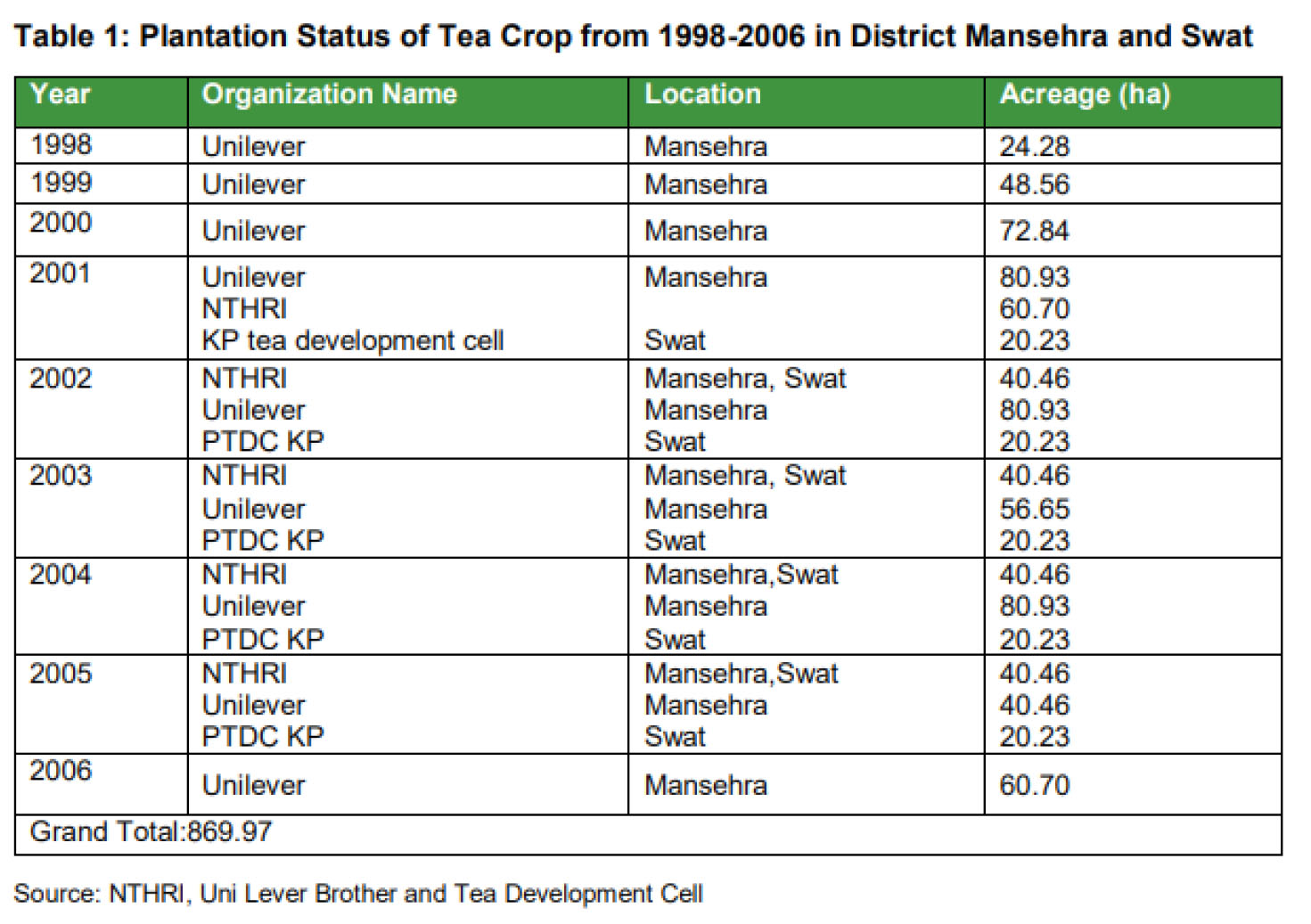

As the earlier mentioned report by the Planning Commission mentions, after the feasibility study conducted by the Chinese experts, the government of Pakistan started tea cultivation in District Mansehra in 1986 through the establishment of Tea Research Station at Shinkiari. Simultaneously, the private sector and the provincial tea development cell of KP also started tea plantations in 2001 in District Swat. For processing black tea from the raw material, a tea processing unit was installed at National Tea and High Value Crops Research Institute (NTHRI), Mansehra during 2001. During the same year the private company Unilever Brother Pvt. Ltd also installed a black tea processing unit at Shinkiari, Mansehra.

The initial response was favourable. From 1998 to 2006 NTHRI, Unilever Brother Pvt. Ltd and the provincial Tea Development Cell of KP made plantation of tea at an area of 869.97 ha in Mansehra, Battagram and Swat. But continued support from the government was sparse; tea growers mostly uprooted their tea gardens in Swat, Batagram and Mansehra and some tea gardens were confined only to Mansehra at an area of 100 ha under Unilever Brother Support which is where Pakistan’s current tea cultivation status lies.

The issues that the farmers faced were typical. During the initial days when the government was promoting growing tea, farmers were interested because the federal and provincial agriculture departments were providing nursery plants free of cost along with inputs to the interested growers. As soon as these schemes ended, interest faded out as there was very little margin between growers’ production cost and revenue.

The growth of tea proved to not be profitable in Pakistan because the price of plucked leaves (raw material for black tea) at Rs 46/kg is much higher in Pakistan than that in the international market i.e. between Rs 20-22 per kg (Unilever based at Mansehra). Pakistan could have become competitive with the international prices by bringing maximum area under tea cultivation (at least 10000 ha), introducing value addition and taking cost reducing measures at all the segments across the value chain. However, this would have required continued political patronage for a while which was missing.

Pakistan gets only 40% of the world average yield. Although the net price at farm gate is higher in Pakistan at Rs 46 per kg as compared to that in India and Bangladesh at Rs 22.90 and Rs 27.0 per kg, respectively but the net return per ha in Pakistan is low at US$1360 compared to international US$1600 due to low per ha productivity.

Last year in August, the government had announced its intention to pursue tea plantations on a commercial scale by planting tea on 1000 hectares in KP, particularly in Mansehra. The plan was launched on the recommendation of Chinese tea experts, the National Tea Research Institute (NTRI). The same body was set up on 50 acres of land in Shinkiari in 1986. Out of the proposed 25,000 acres of land, 10,000 are government-owned forests, 12,000 acres are private land where the Forest Department has planted forests while 3,000 acres of land have been identified in Azad Kashmir.

The plan is ambitious, and the government pointed out how the country has 178,000 acres of tea cultivable land. However, getting even 1000 hectares of this land up and running for tea production would be a tall order. If successful, it could be a start to becoming self-reliant in terms of tea like India. Until that happens, however, every cup of tree we drink in this tea-obsessed country has to be sourced from outside its borders.

After I read and listened to the discussion of the article that you made, I found a lot of interesting information that I just found out.

I think this will really help many people with this knowledge that you have shared. success is always for you, yes!

Hello friends, its great post about tutoring and completely defined, keep it up all the time.

Great delivery. Outstanding arguments. Keep up the amazing effort.

I once again find myself personally spending way too much time both reading and leaving comments

사설 카지노

j9korea.com