Karachi’s patron saint Abdullah Shah Ghazi has been protecting the city from the wild whims and wishes of the Arabian Sea ever since he arrived here as a horse trader in 8 century CE. Sitting atop a hill near the coast, Abdullah Shah Ghazi’s mazar has long served as both landmark and talisman for an entire city. Yet today, as some would argue, it is the saint that needs protection from unbridled real estate development and commercialisation.

Looming large over the shrine is the Bahria Icon Tower. Billed as Pakistan’s first skyscraper it is a 62-storey tall high-rise project owned and operated by real estate mogul Malik Riaz Hussain’s Bahria Town Group. Gigantic, equipped with a seven-story basement parking, and the tallest building in Pakistan the Bahria Icon Tower is also a ghost-town. And Profit has it on good authority that the meg-project is up for sale but is having a hard time finding

Launched in 2009 the project has undergone a number of controversies and has been on hold since 2021. Once a pet project of Malik Riaz, the tower has in its 13-year history been the subject of court case upon court case. The key dispute is over the four-acre plot upon which the 938 feet tall tower stands. According to a reference in the accountability court, the tower has been built on illegally sold government land. On top of this, there have been serious concerns about its impact on Karachi’s cultural heritage because of the sensitive nature of its location next to a religious shrine, and its role in the ecological deterioration of the Karachi seafront.

So what will become of Pakistan’s tallest building? According to sources close to Bahria Town, back in 2021, Malik Riaz stopped development on Icon tower and started the hunt for a buyer. However, Bahria Town immediately faced two issues with this plan. The first was that there were no real buyers for such a massive project. Banks that might want to buy it as an office building would have trouble because it is a multipurpose residential/commercial structure. The second problem was that even if a buyer had miraculously appeared, the project could not be sold because of all of the pending court cases it was caught in the middle of.

Essentially, the legal quagmires that surround Pakistan’s tallest building mean that such a sale is next to impossible. So is the Bahria Icon Tower too tainted to find any takers? If it is, then how will Malik Riaz and Bahria Town get rid of this thorn in their back? And if the project does continue, how will local residents, investors, and municipality officials deal with such a possibility? Profit looks at the origins and story of the Bahria Icon Tower. How it came to be, what the problems surrounding it were, and whether it will ever get up and running or not.

The Bahria Town philosophy

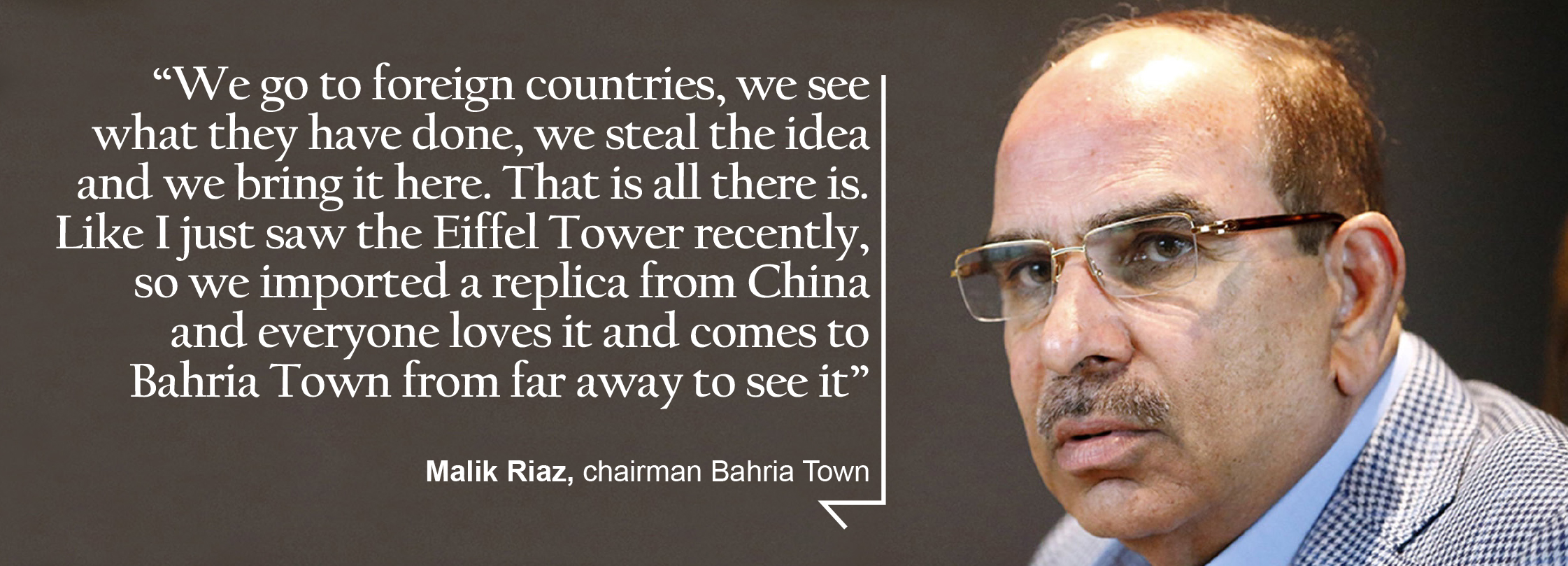

When Malik Riaz first envisaged the Bahria Icon Tower there was only one thing on the agenda: It had to be BIG. The icon tower is quite different from any other real estate project that has the Bahria Town stamp on it. In his decades in the real estate business, Malik Riaz has created his own unique brand of development. In an ‘Aik Din Geo Ke Saath’ interview with Sohail Warraich, Mr Riaz explained that the ‘European’ inspiration behind many of his housing projects is a calculated decision that has proven successful in the Pakistani market.

“We go to foreign countries, we see what they have done, we steal the idea and we bring it here,” Riaz said with candour. “That is all there is. Like I just saw the Eiffel Tower recently, so we imported a replica from China and everyone loves it and comes to Bahria Town from far away to see it.” Largely speaking, the success of Bahria Town has been based on ruthlessness, unrelenting tactics, and a complete lack of originality or imagination that makes their projects safe and familiar in many ways.

But the Bahria Icon Tower went against the grain. While a high-rise apartment and commercial building was nothing new to Karachi, it was an ambitious plan particularly for 2009. According to an Environmental Impact Assessment report from the project’s early days, the multi use commercial building project spanning 60 floors with 59 floors of office space and seven levels of basement parking would be completed in 2012 at an estimated cost of Rs 20 billion. Designed to be one of the tallest buildings in South Asia and by far the tallest in Pakistan, the Bahria Icon Tower was a pet-project for Malik Riaz and one that went against the typical Bahria Town philosophy.

However, the tower’s journey was not so simple. It was not completed by 2012 owing to rising costs of construction and a number of legal problems that it was in the middle of. Take one problem that the tower faced, for example. To build the basic structure of such a project you need cement, rebar and glass. In Pakistan, cement and rebar is widely available but heavy glass is not. Every single pane of glass in all these buildings under construction was being imported.

This cost has been a major factor in building design in the past. That is why you see so many thick, old school cement construction buildings like Creek Vistas. The only glass made in Pakistan is the thin clear sheets for residential windows not the tempered heavy and internally tinted, UV treated glass used in skyscrapers. If someone would start a modern heavy glass facility in Pakistan, they would have a lot of business going forward. According to a different source that is high-up in Bahria Town, this was the time when Malik Riaz started having doubts about the project.

Despite these challenges, the building was topped off in October 2017 and is currently the tallest building in Pakistan. However, it was other problems that have resulted in it continuing to be out of use. The biggest issues have been the court cases surrounding it, which make both running and selling the project next to impossible. However in 2020, when Bahria Town started facing cash flow issues particularly in Karachi, work on the tower stopped and the hunt for a buyer started. The only problem was that there were no buyers.

The sale potential

The Bahria Icon Tower has a unique design and features both residential and commercial spaces. The lower floors of the tower are dedicated to retail shops and offices, while the upper floors are reserved for luxury apartments. The tower also has several amenities, including a gym, swimming pool, and cinema. Based on its sheer size alone, the tower even in its current state has become a city landmark. In fact, the very existence of the tower is testament to the rapid growth and development of Karachi in recent years.

As of 2021, the estimated population of Karachi, Pakistan is around 16.5 million people, making it the largest city in Pakistan and one of the largest cities in the world. It is difficult to determine how many people live in apartments in Karachi, as there is no official data available. However, due to the high population density in the city, it can be assumed that a significant portion of the population lives in apartments.

This is where things get complicated. Malik Riaz has been looking for a buyer. The officials at Bahria Town have said that since there are court cases regarding the building they cannot comment on whether or not they are trying to sell, and that even if they wanted to, the court cases would stop them (more on those later). But Malik Riaz isn’t really the sort of real estate developer that lets courts get in the way of his development. The decision to stop work on the tower and look for a buyer came as the result of cash flow issues, according to one source within Bahria Town.

However, who would buy the tower? There have only really been two examples of entire buildings being successfully bought out in its entirety. One example was when Bank Al Habib bought the centrepoint building from TPL Properties in May 2021. Centrepoint happens to be, quite literally, the center of TPL’s ambitions. This is one of the biggest developments in the real estate sector of Pakistan. Some facts about the building: the 28-story Centrepoint, stands 385 feet high, and has been constructed on 26,226 square feet of land. It has 197,810 square feet of rentable space, with the offices on 17 floors (from the 11th floor to the 24th, and the 26th and 27th floor).

In comparison, Malik Riaz’s project has nearly three times the number of stories that the TPL building had. The second example is when Habibullah Khan sold a real estate property in the biggest deal of its kind to Habib Bank. This indicates that the only real buyers for Malik Riaz’s Bahria Icon Tower would be a bank or a very large corporation looking for new offices.

The problem with that is that the tower is multi-purpose and has residential, commercial, and office spaces. This means it can’t exactly be used just as an office building, unless a bank also decides it will provide residence to its employees in the same building. However, the building is significantly bigger than any other project that has been bought out before. Then there is also the Bahria Town reputation in terms of cutting corners in build quality. The most significant problem, however, are the many court cases that plague the project.

What are all the legal roadblocks?

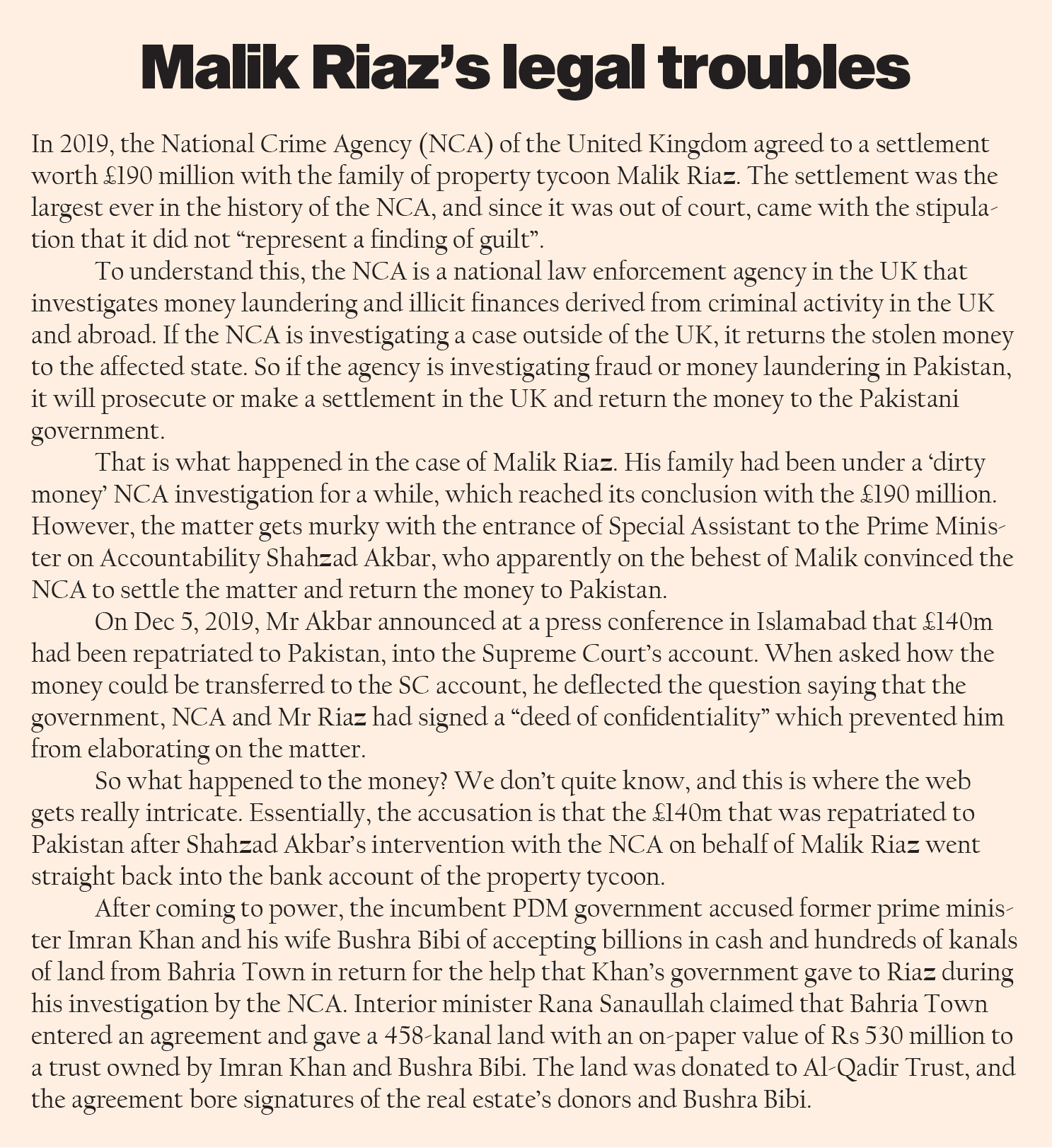

The conflict starts from the 3.68 acres of land that the tower has been constructed upon. In June 2019, the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) initiated proceedings regarding the plot of land that the tower had been built upon. The bureau claimed that the original plot was what is known as an ‘amenity’ plot and had been illegally sold to Bahria Town.

In the world of real estate, an amenity plot is a public property owned and allotted by the government in a particular region or city. These types of plots can only be used for the construction of government offices as well as the establishment of public welfare facilities, such as hospitals, worship places, educational institutions, burial grounds, parking lots, and different types of recreation spots.

Pakistan’s encroachment laws hold that such plots can only be used for public welfare purposes otherwise it would be considered an encroachment. Also, the development authorities in Pakistan can rightfully demolish any illegal construction. In this particular case, the plot was supposed to have been allotted to Bagh Ibne Qasim — which is a park located near the Clifton Beach in Karachi close to the shrine of Abdullah Shah Ghazi and the current location of the Bahria Icon Tower.

As the case unfolded, it turned out that NAB arrested Sajjad Abbasi, the works and service secretary of the Sindh government for his alleged involvement in the Icon Tower case. In a court statement, he admitted to selling the amenity plot to Dr Dinshaw Anklesaria, who worked as the executive district officer of the revenue department. He was claimed to have sold the plot to Malik Riaz, who then constructed the Bahria Icon Tower on it.

In February 2020, the accountability court of Islamabad summoned Malik Riaz, his son-in-law Zain Malik and other accused persons in a corruption case pertaining to the Bahria Icon Tower. The other accused included Manzoor Qadir Kaka (former chief controller of construction), Ahmad Ali Riaz (former director of and CEO of Bahria Town) and Yousaf Baloch (former senator) among others. The Bahria Icon Tower was perceived as an offshoot of the fake accounts case, and it was the first reference wherein Malik Riaz had been nominated as an accused person.

According to NAB sources, all the accused persons had incurred a loss of Rs 100 billion to the national exchequer through the illegal allotment of an amenity (welfare) plot of Bagh Ibne Qasim to M/s Galaxy Construction (Pvt) Ltd (Bahria Icon Tower), where the tower itself was erected. NAB filed the reference before the registrar accountability court, which then placed it before the administrative judge, Mohammad Bashir. According to a senior lawyer from the Bahria Town legal team, Malik Riaz would be unaffected by this. He could file an acquittal plea as the evidence against was seen as weak. Nevertheless, this deal would prevent from contesting elections or holding public office as a plea bargain does not waive the conviction. At this point, his lawyer clarified that the real estate tycoon had no such ambitions and was only concerned with the smooth operations of business.

More recently on 15 February 2022, the Accountability Court adjourned the Bahria Icon Tower corruption reference till March 1, without further proceedings due to the absence of judge Muhammad Bashir. According to the report of the Joint Investigation Team (JIT) that also investigated the fake accounts case, the Bahria Icon Tower was an embodiment of the land grabbing and money laundering trends that undergird real estate development in Pakistan.

Finally the Accountability Court (AC) declared October 7 as the date to announce its verdict on the Bahria Icon Tower case against Malik Riaz and others. In the previous hearing, the court had directed NAB to determine if the plot’s value was based less than Rs 500 million. NAB itself had already filed a reference against Malik Riaz and others for the illegal land allotment.

In December 2022, however, it turned out that Malik Riaz got off scot-free in the reference related to the illegal allotment of an amenity plot for his skyscraper in Karachi. This happened when an accountability judge claimed he did not have jurisdiction to hear the case after a change in the law by the incumbent federal government. Accountability Judge Mohammad Bashir, while disposing of the applications filed by the suspects in the BIT reference on the basis of amendments in the National Accountability Ordinance (NAO) introduced by the current government, observed that since he lacked jurisdiction to hear the reference, the case is being remanded to the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) for onward transmission to the competent forum.

The project was intended to be completed in 2023. However, the management of Bahria Town seems reluctant to discuss the controversies and developments related to it. Nadia, the spokesperson of Bahria Town informed Profit, “since the project has not been completed yet, nothing can be said about it.” She was hesitant to discuss any aspect of the project, waiting for the project’s eventual completion to answer all questions.

Social Impact

Despite Karachi’s violent local politics, the potential of the Sufi Saint. In times of heartbreak, the saint has greeted his devotees with open arms. People have found prayer, food, music and ultimately, a safe haven at his rendezvous. However in the prevalent kingdom of private developers and imagined concrete jungles, the sustenance of such vibrant social practices is a big question mark. Elite-oriented developed practices have resulted in the increasing gentrification and by consequence,the flattening of social diversity. While signal-free corridors are being built for car-owners, there are no footpaths for the millions who walk to work. While high-rises boast infinity pools, clean water for basic hygiene isn’t available to the people. The Bahria Icon Tower is another example of the classist lens that shapes urban development in Pakistan.

While Abdullah Shah Ghazi’s grave’s site is significantly older, the shrine complex was built immediately after Partition and became a renowned site for pilgrimage. The street adjacent to the shrine was filled with pilgrims and many vendors selling Ta’wiz, flower garlands and food. Supplicants, beggars and musicians were widely present. Tolerance was observed for the itinerant and the homeless who were accommodated in the shrine’s precincts. Now, while mammoth shopping malls are being constructed, the streets are being cleared of local vendors who are considered a menace to public security. The developers gained the right to transform the site and according to rumours, incentives for cooperation were provided- involving offers of free pilgrimage trips to Mecca. This offer extended to both patrons as well as visitors.

According to the shrine custodian, a billion rupees were channelled by the developer into the expansion and renovation of the shrine. The shrine has been cordoned off by an enormous boundary wall that demarcates the shrine from the street. Now, visitors have to navigate their way through the cordon protected by Bahria development group’s private security guards. The surveillance is further complemented by tighter restrictions of drug-use and scrutiny of the homeless. Furthermore, there used to be a guest house for the pilgrims who would visit the shrine. This had been functioning since the past sixty years, but has now been omitted from the new master plan, because of the perceived security threat from the pilgrims. Previously seeking refuge at Ghazi’s shrine, the devotees now find themselves in Riaz’s prison.

In the private developers’ domain, the idea of a public space is becoming increasingly exclusionary.

Between the Bahria Icon Tower and the shrine, a lane stretches from the shrine to the sea. Very often, people would walk across this lane towards the sea, and visit the Play Land and aquarium along the coast. Developed along the lane was a well-organised market for food, seashell trinkets, art work and souvenirs, which the visitors took great delight in. However, the market no longer exists and the sea is also inaccessible from the lane. Now, the lane opens to the Beach View Park where one has to pay for entry. The lane’s hawkers have also shifted to other locations where they complain of reduced earnings. Many have been forced to forego their traditional vocation and acquire jobs with contractors and small businesses in the vicinity. While the Bahria Icon Tower may occur as a symbol of modernity in a despaired Karachi, its physical, economic and social space is largely inaccessible to the non-elites. Such development practices are widening the class-gap.

Cultural Loss

This project too has been subject to resistance both by residents and local NGOs due to its problematic location between two key historic monuments- the shrine of Abdullah Shah Ghazi and the Jehangir Kothari Parade. The opposition lamented that this project would jeopardise the infrastructure of these two historical sites.

According to public reviews and local reports, the Bahria Town’s construction juggernaut was enabled by digging up large chunks of Shahrah-e-Firdousi and a section of Sharah-e-Iran. In response to the municipal objections, the company offered to construct an underpass and a flyover in the surrounding area. The flyover project was also financed and built by Bahria Town under the supervision of the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC), with an estimated cost of Rupees 1.89 billion. This was unprecedented for a project of such magnitude to be outsourced by a private corporation. It’s also believed that the construction of the flyovers and underpasses had been initiated without meeting the legally mandated environmental assessments. Malik Riaz maintained a close relationship with the former president Asif Ali Zardari, which seems to be a factor of the efficiency and the discreteness through which the project was being executed.

Not only the mazar is affected by this construction havoc. There is also a temple next to the Shrine, the Sri Ratneshwar Mahadev Temple, which is venerated by Hindus and is believed to be 150 years old. The underground temple, predicated on six levels, is on the brink of collapse. Both the shrine and the temple are central to the historic and cultural fabric of Karachi. Therefore, both heritage lovers and advocates raised concerns about the damage incurred to the shrine and temple due to the ongoing excavations. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) also voiced concerns about the construction’s dire impacts on the Mahadev Temple.

Similarly, the design of the underpasses violated heritage laws, as the heritage site of Jehangir Kothari Parade was encroached upon and the roof of the Mahadev Temple was damaged. The Jehangir Kothari Parade is a historic emblem, which is now injured and virtually concealed from the road because of the new underpass.

Conclusion

So here is what it comes down to. In 2009, Malik Riaz envisioned Pakistan’s first skyscraper and wanted Bahria Town’s name on it. The project came to life, land was acquired for it to be built on, and over the next decade Pakistan’s tallest building came together story by story. In the middle, people invested in the project by buying files and booking certificates — typical of most real estate projects in the country.

Now, when the project should have been completed and the tower on its way to being occupied, it sits empty collecting dust. Why? Because the land on which it was built became the centre of an accountability bureau trial. The tower over time became enough of a thorn in Malik Riaz’s back that Bahria Town tried to sell the project but couldn’t find any serious buyers on account of the legal maze it is stuck in. On top of that, it has caused havoc because of its location close to a sacred shrine.

But here’s the catch. The 62-story high Bahria Icon Tower is here and it is here to stay. As the tallest building in Pakistan, an investment of this size will not go to waste. Whether Bahria Town is able to extricate itself from this mess or not is yet to be seen. But such a massive construction must be put to good use and not allowed to go decrepit.

Such a ridiculous first para hurting the sentiments of those having huge respect for the saint. Do you see him coming out and asking for protection from ‘unbridled real estate development and commercialization’?

Lol we need multipurpose high rise building a for commercial & residential purpose. Enough of deforestation for commercial & residential areas. Look at all other countries what they have done to their port cities while we want to save a shrine & we slap a ban on high-rise building for what non sense reasons !?

Love the article but disagree with the final paragraph. Why would it not go to waste? There’s plenty of examples from the world over of skyscrapers abandoned misconstruction and getting taken over by homeless families (see Tower of David in Caracas). A tower of this scale will likely meet this end the longer it stays unfinished.

Welcome to Versatile Coupons, the final location for getting a versatile deal on your internet-based buys. Our central goal is to assist customers with enjoying you find the best arrangements and limits on the items you love. We comprehend that setting aside cash can be intense, particularly while shopping on the web. That is the reason we’ve made it our objective to present to you the best-in-class coupons and markdown codes from top retailers. Whether you’re looking for garments, gadgets, or home merchandise, we take care of you.

wow!

Nice prose, very well worded by SO but writer has used anti-project stance which has thus tinted his intellect. Be fair n balanced and leave judgement to readers I always assume should be the purpose of any good writer.

However, after a very long time I have enjoyed an eloquent article n I liked it the way Shahab has tackled it with details n great vocabulary. Speaks of his acumen n intellect. I suggest he must use his capabilities at rather better dynamic platforms