There is no crop in the world that is grown more than wheat. Covering almost one-sixth of the arable land in the world it is the food-crop with the highest demand globally that leads every other crop in the world including rice, maize, potatoes, and sugarcane.

In Pakistan, the story is not particularly different. Wheat and wheat based products account for 60-70% of all caloric intake in the country’s population. At 125 kilograms per year, Pakistan’s per capita consumption of wheat is one of the highest in the world. Correspondingly, the country is also the eighth largest producer of wheat in the world and one of the stated aims of the state has always been producing enough wheat to meet local demand and maintain a level of food security.

Yet these numbers pose a problem. Pakistan’s status as a wheat powerhouse is largely due to the vast amounts of cultivable lands in the country, particularly in Punjab. The reality is that for some years Pakistan has been unable to meet even its own wheat needs and has had to import the essential commodity which provides most of the caloric content for Pakistan’s population.

In November 2022, Pakistan approved a deal worth nearly $112m to import 300,000 tonnes of wheat from Russia to meet its domestic shortfall in the aftermath of the devastating floods that hit the country.

So what are the problems that Pakistan’s wheat crop faces? Largely, poor farm science has meant the yield of Pakistan’s wheat is far lower per hectare compared to other major producers. At the same time, a growing population has meant demand has risen at a faster rate than the amount of wheat we grow. On top of this, Pakistan has very serious issues with its agriculture supply chains — which at times have caused losses upwards of a billion dollars in crops forfeited because they could not be transported and stored in time.

Pakistan’s wheat — zooming in on the past three years

Before we get into the details of wheat economics in the country, it is important to understand the state of the wheat crop in Pakistan over the past few years. Since 2020, the wheat crop in the country has seen a fast-changing landscape and serious ups and downs. Look at the following statistics:

- In 2020-21, Pakistan produced 27.4 million tonnes of wheat. This was up by more than 2 million tonnes from the previous year and was the highest yield of wheat the country had ever seen. This was also significant because between 2008-09 to 2019-20 the annual wheat production in the country had stayed steady between 23-25 million tonnes.

- However in 2021-22, production fell again by a million tonnes but still clocked in at over 26 million tonnes. While this was a dip from the previous year, it was still higher than the yield in 2019-20 when just over 25 million tonnes of wheat was produced.

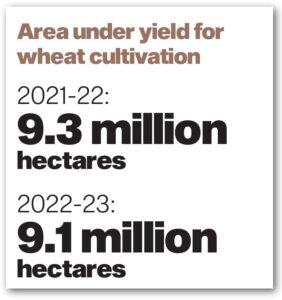

- This year, the crop’s status is finely balanced. A meeting of the Federal Committee on Agriculture (FCA) reported that Pakistan is estimated to produce 26.81 million tonnes of wheat during the ongoing Rabi season against the target of 28.4 million tonnes. Now, while the production is missing its target and the area under wheat cultivation also reduced from 9.3 million hectares to 9.1 million hectares, the production of 26.81 million tonnes of wheat this year reflects an increase of 1.6 per cent over the previous production year.

So what does all of this tell us? On the one hand, we can glean from this data that wheat production in Pakistan has been steady over the past few years. It has not been growing, but it has also not been significantly falling. However, this is not enough wheat for a country where it is the biggest source of nutrition for the population. In fact, even in 2021 when Pakistan got its record bumper crop of 27.4 million tonnes, it had to import 2.2m tonnes of grain to meet local requirements and build strategic reserves of 1m tonnes. Pakistan’s current population stands at 231.4 million people. That means in 2021 Pakistan produced around 95 kilograms of wheat for every single one of its citizens. However, the overall consumption of wheat per capita in the country is 120 kilograms per person — meaning every person has to consume around 25 kilograms of wheat that is imported.

The very next year in 2022, a 15 per cent drop in the domestic wheat yield due to shrinking acreage, poor application of fertiliser, water scarcity, limited certified seeds and the disruption of supply chain because of the floods, resulted in having to import wheat from Russia. This year, the government had predicted over 28 million tonnes of wheat production but is now looking at just around 26 million tonnes instead and like previous years will be reliant on imports. While the reliance on imports is nothing new, it is worth looking at why the government sets these targets and what role it has to play in the wheat cycle.

Targets and their questionable effectiveness

Of all the bad habits the government of Pakistan has, perhaps one of the worst is the one picked up by the Ayub Administration in 1958 from the Soviet Union of building a government that assumes that it operates in a planned economy, even as it presides over at least a semi-open market economy.

Since then, the practice has continued with the government announcing ‘targets’ every year for all manner of economic indicators, including many it has almost no control over at all. Profit has pointed out in the past how ridiculously high cotton production targets actually end up belittling the efforts of farmers. And much like cotton, wheat is another crop in which the bureaucrats stuck in the 1960s continue to announce targets for the commodity. This is despite the fact that the government of Pakistan does not own any wheat farms, nor most of the banks that do not lend to the farmers anyway, nor any of the companies that supply farmers with what they need.

What the government does do, however, is conduct a wheat planting campaign every year. Targets for planting and yields are set and procurement targets are agreed upon. Thousands of extension agents and agriculture students are instructed to fan out across the country to encourage and advise wheat farmers.

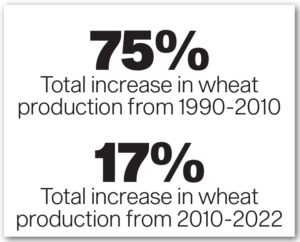

The results are mixed. On the one hand, with the help of better seeds, this system has helped increase wheat production. In 1990 production was 14.4 million tons and crossed 25 million tons in 2011 — an increase of 75% in about 20 years. However the inefficiencies of this system have been starkly exposed in the 12 years since. From 2011 up until now, however, it took 10 years before production hit a new record of 27.5 million tons in 2021 (a 10% increase in 10 years) before falling back to 26.4 million tons in 2022.

“There is a looming shortage of wheat in the next fiscal year as well and the government will have to count on the import of wheat in order to meet the domestic requirements of staple food. The import of wheat is going to witness an upsurge at a time when the country is facing the worst-ever dollar liquidity crunch,” says one top government official.

“There will be no other option but to import 3-3.5 million tonnes of wheat for the next fiscal year in order to meet domestic as well as Afghanistan’s requirements. This is more than the import target of 2.6 million tonnes of wheat for the current fiscal year.”

So then what are the problems?

This is where we stand. Pakistan between 1990-2010 increased its wheat production significantly (by 75%) but has since been stuck at the same level while the population and demand for wheat has been steadily increasing. This has taken Pakistan from being an exporter of surplus wheat to a net importer.

The difficulties of handling the wheat market became clear in 2019 when government estimates suggested a wheat surplus and some 500,000 tons were exported. But then, as domestic market conditions tightened, the government was forced to change gears and import some 3.4 MMT to meet consumer needs and help rebuild the country’s wheat stocks, at a much higher cost. The main reason behind this was that Pakistan’s agricultural supply chains were decrepit. There are many bottlenecks that make such losses inevitable. Pakistan desperately needs better storehouses, direct financing access to farmers instead of through exploitative middle-men, as well as better machinery for threshing. Most wheat is harvested by hand in the initial seasons but machines are needed for large scale harvesting. Most farmers have outdated equipment which results in significant losses.

Overall there needs to be a push towards financial access to farmers by collateralizing commodities for loans, and also creating strong incentives for crop testing, grading, and standardisation, proper storage, reduction in post-harvest losses, and preservation of crop quality for exports.

In a 2022 research article, Ghasharib Shoukat, the head of product at Pakistan Agricultural Research, and Daud Khan, formerly a UN staff officer, argue that slower growth in wheat production has made Pakistan increasingly dependent on foreign supplies. Two to three million tons — around 10% of needs — have been imported in the last few years. However, high dependence on imported wheat is of some concern. International markets have been volatile and turbulent in recent times, and this may well be a continuing feature for the coming years if not coming decades.

“A good option for Pakistan would be to try to increase domestic wheat production. At present the average yield of wheat is around 3 tonnes/ha, substantially lower than other comparable countries. There is a huge scope to increase this yield through relatively simple changes in the production system such as reduced tillage, increased use of certified seeds, use of seed drills, a better match between fertiliser applications and soils, and application of micro-nutrients. There is also a large potential scope to reduce on-farm and off-farm losses through improved harvesting, bulk handling and storage in modern silos. Climate change poses problems for Pakistan as it does for many other countries. However, it also creates opportunities. Changing rainfall patterns have resulted in higher precipitation in some of the arid areas in Balochistan and Sindh. And this has expanded the potential area for wheat. With relatively minor investments, for example, in water storage (small dams) and water spreading technologies, these areas could, in a good year, get a reasonable wheat crop from post-monsoon residual moisture,” they write.

To improve our overall farm productivity for wheat, better farming techniques and seeds research is a must. But these are the obvious suggestions. One other way of going about it would be to possibly focus on provinces other than Punjab. In the current fiscal year, Sindh surpassed its sowing target of wheat as the staple food was sown on an area of 2.945 million acres as against the sowing target of 2.79 million acres for the current fiscal year. According to initial estimates, Sindh has harvested 25 percent of its cultivated area with per acre yield recorded as 40 tonnes. In KP, the wheat was sown on an area around 1.933 million acres as against the envisaged target of 2.22 million acres, achieving only 87.07 percent target. Balochistan achieved only 77.21 percent wheat sowing target as wheat was sown on 1.05 million acres as against the target of 1.36 million acres.

Even in 2021 when Pakistan recorded a record yield, a big part of pushing wheat over that threshold was increased yield in Balochistan and Sindh. Along with more research and better farm practices, if money is invested in the right place, Pakistan could once again become a net exporter of wheat rather than having to rely on imports and set lofty targets every year.

It is worth noting that this is very much possible. Wheat production in the country has increased from 3.35 to 25 million tonnes (617%) during 1948 to 2011 whereas the increase in area was from 3.9 to 8.9 million hectare during this period (129%). Grain yield (Kg ha) has been increased from 848 (1948) to 2,797 (2013) with an increase of 317 percent. Over the past three decades, increased agricultural productivity occurred largely due to the deployment of high-yielding cultivars and increased fertiliser use.

A report of the Trade Development Authority of Pakistan has also pointed out how there has been an introduction of semi dwarf wheat cultivars. As a result, wheat productivity has been increased in all the major cropping systems representing the diverse and varying agro-ecological conditions. Improved semi-dwarf wheat cultivars available in Pakistan have genetic yield potential of 7-8 t/ ha whereas our national average yields are about 2.8 t/ha. A large number of experiment stations and on-farm demonstrations have repeatedly shown high yield potential of the varieties. National average yield in irrigated and rainfed area is 3.5 and 1.5 t/ha, respectively. The progressive farmers of the irrigated area are harvesting 5.5 to 7 tonnes wheat grain per hectare.

The slow-down has only really happened in the past 12 years and even then some of the lower yields have been attributed to climate change. There are some similar international examples at hand. From 1960 to 1980, Russia was a major importer of wheat requiring as much as 47 million tonnes in 1985. A major push after this has made Russia the world’s largest wheat exporter with overseas sales of about 40 million tons. With dedicated effort to improve growing and supply chain, a country like Pakistan with lots of cultivable land and favourable climatic conditions can very much see a turnaround of such proportions as well.