In what can only be described as a rare cosmological event, the government of Pakistan might have had a good idea: A carbon tax on petrol.

As a state, Pakistan has never really learned how to collect taxes. There are long, tedious explanations for why this is so, but to cut a very long story short, taxation is centralised. That means the federal government through the FBR collects almost all taxes (even the ones that should be collected by provinces under the 18th amendment) and then those collections are then given to the provinces in the form of the NFC award leaving the federal government with very little spending money.

The proposed carbon tax would make life much easier for the federal government. For starters, it would give them revenue that they wouldn’t have to share with the provinces. It would placate the IMF, which has been on Pakistan’s case to rationalise petrol pricing and move towards a Value Added Taxation (VAT) system to price petrol. It would also allow the government to show off how green it is to international lenders, enabling the issuing of green bonds and e-bonds, and gaining access to all sorts of funds cheaper from multilateral financial institutions.

What the tax definitely won’t do, of course, is make petrol cheaper. Normally, the purpose of a carbon tax would be to discourage the use of petrol. But alternatives to using petrol are next to non-existent in Pakistan. Electric vehicles are unaffordable and often non scaleable. Public transport is in shambles. In this particular case, the government of Pakistan would be imposing a carbon tax less to be a green government and more as a clever bit of accounting that would allow the federal government to pocket taxes through the sale of petrol.

But that isn’t quite the problem one might think it to be. Petrol prices are going to rise no matter what. Pakistan is currently on a mission to enter a much larger IMF facility than the one that just ended. The IMF is playing hard to get and the government knows it has no other choice. The only thing they are changing is how they increase the price of petrol and gain benefit from it. The only thing stopping them is political will.

Every government that has ever come and gone in Pakistan has had to deal with the politicisation of petrol. If the prices are high, the opposition cries foul. If they fall, the government takes credit for every rupee. A commitment to a carbon tax would mean a commitment to keeping petrol expensive, even when there is an opportunity to decrease them. And as has become clear to Profit over the past few days, the opposition to this is already rolling in.

Petrol pricing and the carbon tax

It might seem like a non-event, but it goes to the heart of everything wrong with taxation and fuel policy in Pakistan. On the 16th of May, the government of Pakistan announced it was cutting petrol prices by Rs 15, bringing them down to Rs 273.10 per litre.

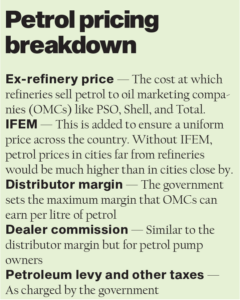

Petrol prices in Pakistan are determined by a number of factors. The main input is the international price of crude oil, which is imported into the country by oil refineries which then process it and turn it into fuel. The price of fuel after processing is what is known as the ex-refinery price. But then other things get tagged along onto this. A margin is added to make sure the price is uniform throughout the country and not cheaper in areas close to the refinery, distributors naturally take a cut, and then dealers and petrol pumps also charge their own service premiums. On top of this, the government also takes a cut. Petrol is currently subject to a petroleum levy of around Rs 40 per litre.

As we mentioned at the beginning, the government is not good at collecting taxes because there is only one tax collector with not enough infrastructure to keep an eye on everything. So the levy is charged to the end consumer and directly transferred to the FBR.

The IMF has long held, and correctly so, that this is a counterproductive system. The fund’s argument is that a VAT system should be implemented in which the value added at each stage of a product getting to the end consumer should be taxed. Without getting into too many details, this would mean the refinery would be charged a tax first, then the transporters, then the distributors and so on and so forth until the final price hits the markets and the tax is passed on to the consumer. This would not just mean that the tax on petrol would not be arbitrarily set (as the petrol levy is right now), it would also help document the economy better.

As part of this, the IMF wants the government to increase the sales tax on petrol at different stages. In the previous budget, the fund had recommended 18% GST be charged on petrol products. But this poses a problem for the government. One of the biggest earners for the federal government is in fact petrol. The government actually budgeted in a way that it expected to collect nearly Rs 900 billion from the petroleum levy. But the sales tax on petrol would be subject to the NFC award, which means the government would have to share the spoils with the provinces.

This is where the carbon tax comes in. A carbon tax is a tax governments around the world can impose on industries that produce and release carbon dioxide into the environment through their business endeavours. Theoretically a carbon tax could be implemented on any industry that burns fossil fuels. The tax is calculated in proportion to their carbon content.

So if an industry produces 1 unit of carbon, the government can charge a certain percentage of their production. In the case of a carbon tax on petrol in Pakistan, the easiest way to go about this would be to charge the oil refineries. Remember, oil refineries are the companies importing oil into the country. The government can calculate an average rate of how much carbon is emitted per every barrel of crude imported. This would directly tax the refinery which would help in documentation, thus fulfilling the IMF’s objective of wanting a VAT system.

On top of this, it would also mean goodies for the government of Pakistan. The government, as per sources, is hoping that the imposition of a carbon tax would help Pakistan convince the IMF to give them a better deal through their Resilience and Sustainability Trust, which is a pool of money they to help low-income and vulnerable middle-income countries build resilience to external shocks and ensure sustainable growth, contributing to their longer-term balance of payments stability. It complements the IMF’s existing lending toolkit by providing longer-term, affordable financing to address longer-term challenges, including climate change and pandemic preparedness.

As reported earlier by Dawn, carbon tax was one of the measures being deliberated that could also help garner international financial support for newer aid instruments, including green and e-bonds and cheaper loans and grants from multilateral institutions. The future development programme is already being aligned with climate public investment management benchmarks, the sources added.

The problem with the intention

Now here’s the rub. The government of Pakistan is not quite considering this carbon tax with the purest of intentions. In normal circumstances, the goal is to decrease carbon emissions by discouraging the use of whatever product is being taxed.

This would not be the first time that petrol was taxed on an emissions basis anywhere in the world. Europe is a very good example, where a study of 26 countries found that fuel taxes have a moderate impact on general road emissions and, in some cases, also on passenger car emissions. The study also found that while increasing fuel prices was a challenge politically, governments should stress the growing economic affordability of fuels and the negative consequences of car transportation.

It would be foolish to discount entirely an effect that such a carbon tax would have in Pakistan. The demand for petrol has fallen due to inflationary pressure over time. In the first half of the fiscal year 2024, the government made record breaking revenues through the petroleum levy. However, sales of petrol have gone down 6.6% year-on-year in the first half of the fiscal year.

And while inflationary pressure can reduce petrol usage, it can never really be enough. In the case of petrol in Pakistan, however, the demand is very much inelastic. There is no infrastructure either for electric vehicles or for public transport that can easily convince the public to switch from using cars and motorbikes. People need to buy fuel to get to work and to commute in their daily lives. Reductions could come from workplaces giving more work from home days or people with cars switching to bikes and those with multiple cars cutting down the number of their vehicles. However, the changes will only ever be nominal.

The problem with our Santa Claus government

This is where we stand. The IMF wants the government to implement an increased sales tax on the purchase of petrol of around 18% which is standard in the rest of the country. The government is hesitant to do this because the money collected from those taxes would be subject to the NFC award and distributed to the provinces. A carbon tax allows the government to tax refineries directly at a set rate and earn revenue that they can keep for the federal exchequer.

The IMF, in its definition of a carbon tax, explains that its purpose is “addressing climate change by reducing greenhouse gases, carbon taxes can also generate more immediate environmental and health benefits, particularly by reducing deaths that result from local air pollution. They can also raise significant revenue for governments, revenue they can use to counteract economic harm caused by higher fuel prices. For example, governments could use carbon tax revenue to ease the burden of taxation on workers by lowering personal income and payroll taxes. Carbon tax revenue could also fund productive investments to help achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, including reducing hunger, poverty, inequality, and environmental degradation.”

But this will pose a problem to the politicians running the government. Petrol prices, as we mentioned before, are highly politicised. Governments want to reduce the prices as much as they can and one of the major reasons that led Pakistan to its current economic climate is in fact the misguided subsidy first implemented by the Imran Khan administration and then continued by the PDM government. Through a petroleum levy, the government can easily change the price of petrol when it feels it is politically expedient.

However, if a carbon tax is imposed, the government will be beholden to it. The tax will pass on to the consumer and the government cannot risk removing it because that will risk alienating the international financiers that Pakistan is hoping to access through its green policies. It will also risk trouble with the IMF and not be eligible for the green bonds and e-bonds they are currently eyeing.

Implementing the carbon tax will require political will that the government may seriously lack. A GST system would help the provinces. The PML-N coalition partner, the PPP, would be interested in getting this revenue for Sindh and the prime minister’s own niece is in power in the Punjab. In addition to this, Deputy Prime Minister Ishaq Dar sits on the Council of Common Interests where the finance minister does not currently have a seat. Here, matters of the NFC could be discussed. The Deputy Prime Minister is already well known to favour cuts in petrol prices to gain political capital, which will make the idea of a carbon tax even more difficult to implement.

All in all, while it may not exactly be aimed at going green, the carbon tax is a good idea that can have a win-win effect. The federal government will collect money it desperately needs and the IMF will also be happy, as well as give access to green financing. Petrol prices will go up in any case, whether it is through GST, international oil markets, or through a carbon tax. But the last option gives Pakistan the opportunity to make the best of a bad situation.

Beating that old drum again

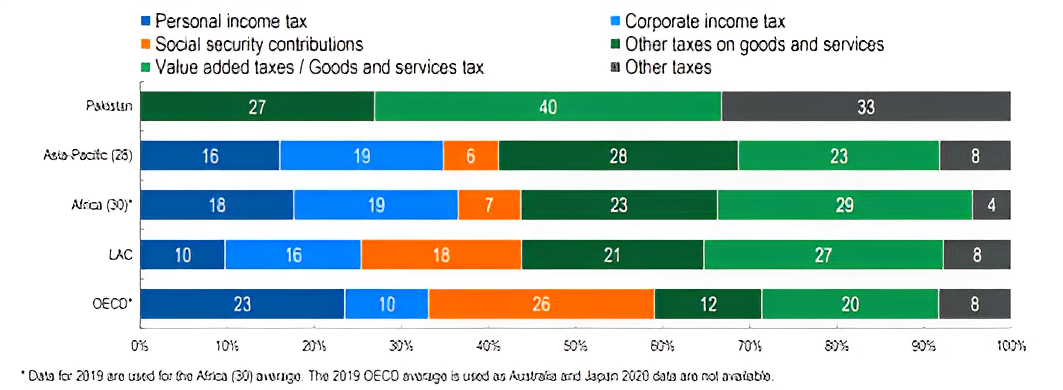

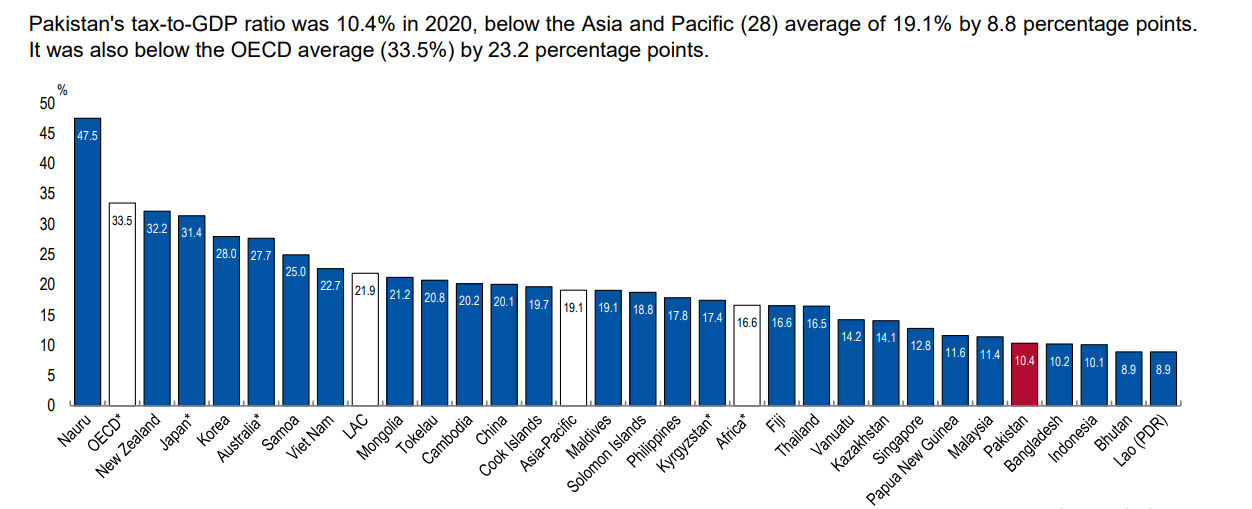

This is something we’ve said before and will continue to say again and again. The real problem is that Pakistanis are taxed unfairly and those that should be paying the lion’s share end up paying nothing. Just take a look at Pakistan’s tax structure. Tax structure refers to the share of each tax in total tax revenues. The highest share of tax revenues in Pakistan in 2020 was derived from value added taxes / goods and services tax (39.8%). The second-highest share of tax revenues in 2020 was derived from other taxes (33.3%).

In comparison to Pakistan, countries in the Asia-Pacific region only collect about 23% of their taxation from goods and services taxes — meaning Pakistan’s average is almost double. Why is this the case? The biggest reason of course is that taxation in the country is centralised. The FBR collects almost all taxes (even the ones that should be collected by provinces under the 18th amendment) and then those collections are then given to the provinces in the form of the NFC award leaving the federal government with very little spending money. In an earlier interview former Finance Minister Dr. Hafiz Pasha, while talking to Profit, lamented that, “We as a country have failed to implement the beautiful 18th amendment. The implementation has been slow and weak.”

Since the share of the provincial governments, under the NFC awards, over the last few years has been increased from 40% to around 57%, it has provided the provinces with very little incentive to develop their own revenue sources. Despite having access to the two biggest cash cows, services and agriculture, the share of provincial tax revenue is close to 1% of the GDP.

The solution of course is right in front of us: devolution. More than just being a third tier of democracy, having a local bodies system means having a new economic process. In essence, it is not just a new administrative stratification, but also involves the dispensation and spending of money. Things such as education and health that people automatically look towards the provincial government for would now be handled by local representatives. Perhaps most crucially, the ability of local governments to collect taxes and release their own schedule of taxation allows them to make their own money and spend it on themselves rather than waiting for the benevolence of the provincial or federal government.