One by one, the foreign firms are coming back to Pakistan’s capital markets.

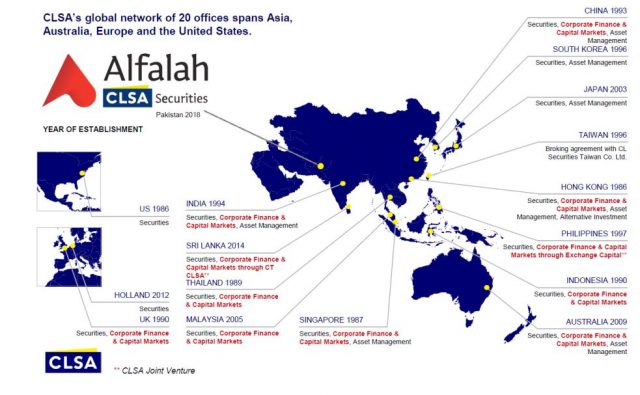

On August 30, CLSA, the Hong Kong-based investment bank formerly known as Credit Lyonnais Securities Asia, formally announced that it has re-entered the Pakistani market after an absence of approximately 17 years, acquiring a 24.9% stake in Alfalah Securities, the securities brokerage and investment banking arm of Bank Alfalah.

In doing so, it has become the second pure-play foreign investment bank to enter the Pakistani market since the re-inclusion of Pakistan into the MSCI Emerging Markets index. EFG Hermes, the Egyptian investment bank, was the first.

Following CLSA’s investment in Alfalah, the company will be called Alfalah CLSA Securities. Both the current chairman of the board, former Engro CEO Aliuddin Ansari, and CEO Atif Khan will acquire a combined 12.6% share in the company. The remainder will be owned by Bank Alfalah, with a small portion owned by the International Finance Corporation, the private sector investing arm of the World Bank.

While it may be tempting to see these two firms setting up shop in Pakistan as the start of a new trend, the reality is much more complicated. CLSA’s decision to enter the Pakistani market is motivated in part by its history in the country, and in part by its current ownership structure.

The investment bank founded by financial journalists

In many ways, CLSA is a creature of both the British era in Hong Kong as well as the boom in East Asia’s economies in the 1980s and 1990s.

The company was founded in Hong Kong in 1986 as Winfull Laing & Cruickshank Securities by former business journalist Jim Walker. Walker was soon joined by two other former journalists: Gary Coull, as head of the dealing room, and Malcolm Surry, as head of research. All three had worked at the South China Morning Post; neither Coull nor Surry had any experience in securities brokerage.

In 1987, the company was acquired by Credit Lyonnais, which at that time was one of the largest banks in France. That gave the company its new name: Credit Lyonnais Securities (Asia), or CLSA.

Although it was founded in Hong Kong, CLSA quickly expanded globally, eventually opening up offices in 17 cities across East Asia as well as in London and New York.

In 1992, the firm sent a young man from its London office named Ali Ansari (yes, the same one who went on to become CEO of Engro) to Karachi to create a presence in the Pakistani market, shortly after the government of Pakistan started liberalizing the financial services sector, including the capital markets.

By 1993, the company had been able to acquire a full brokerage licence and began its securities brokerage business in Pakistan. “We were always profitable in Pakistan. The profits were not huge, but it always made money for CLSA,” said Donald Skinner, group secretary at CLSA, in an interview with Profit.

“The other thing that Pakistan gave us was great talent. We were able to recruit some very good analysts who then went on to other parts of the business in other parts of the world,” said Skinner.

CLSA’s presence in Pakistan lasted until 2001, when the company closed up shop and departed Pakistan.

In the intervening years, CLSA’s parent went through several changes, going from being majority state-owned by the government of France to becoming fully privatized in 1999, to being sold off to Credit Agricole in 2003.

In 2012, Credit Agricole sold a 19.9% stake in CLSA to CITIC Securities, China’s largest investment bank and a subsidiary of the state-owned CITIC Group. The next year, CITIC bought the remainder of CLSA. All in, the transaction cost CITIC $1.25 billion.

Why come back to Pakistan now?

In his interview with Profit, Skinner was careful not to label CLSA’s return to Pakistan as just another product of Chinese interest in Pakistan that stems from the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). He sought to highlight CLSA’s independence and its own reasons for wanting to return Karachi’s capital markets.

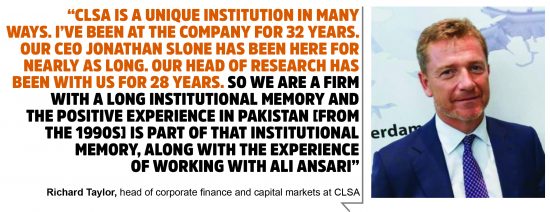

“CLSA is a unique institution in many ways. I’ve been at the company for 32 years. Our CEO Jonathan Slone has been here for nearly as long. Our head of research has been with us for 28 years. So we are a firm with a long institutional memory and the positive experience in Pakistan [from the 1990s] is part of that institutional memory, along with the experience of working with Ali Ansari,” he said.

But in an interview with the Financial Times, Richard Taylor, the head of corporate finance and capital markets at CLSA, laid out a much more CPEC-related reason for wanting to expand into Pakistan. In an articled dated August 12, Taylor linked CLSA’s interest in Pakistan directly to its ownership by CITIC, and therefore their interests in CPEC: “Citic has a broad range of businesses… We see ‘Belt and Road’ opportunities with Citic in places like Pakistan and Bangladesh,” referring to the wider One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative, of which CPEC is tangentially a part.

The Ali Ansari factor

But while CPEC is probably playing a role in CLSA’s decision to re-enter Pakistan, a significant part of the decision may quite simply be Ali Ansari’s past relationship with the firm, and his and Atif Khan’s success in making Alfalah Securities a force to be reckoned with in Pakistani capital markets, particularly on the retail brokerage business.

Alfalah Securities earned Rs144 million in revenue from its retail brokerage business in 2017, according to Bank Alfalah’s financial statements. That number is a pittance compared to the Bank Alfalah’s overall revenues, but the growth in that business has been rapid. In 2014, for instance, the retail brokerage earned Alfalah Securities less than Rs3 million in revenue.

The reason for the growth in the business appears to be a willingness of Alfalah to invest in making its securities brokerage firm – hitherto much more focused on institutional clients – friendlier towards retail consumers, particularly with respect to the adaptation of technology. For instance, Alfalah now offers one of the most robust stock trading apps on both iPhones and Android smartphones, which makes its services much more attractive to tech-savvy middle-class investors.

Hence it comes as no surprise that Alfalah Securities is beginning to earn a profit on its retail business. The company earned a pre-tax profit of Rs31 million on retail brokerage in 2017, the latest year for which financial statements are publicly available. In other words, it may simply be the fact that CLSA has an established relationship with a leading Pakistani executive who happens to be the chairman of the board of a well-established brokerage firm that is on the verge of a serious take-off in its revenues.

The broader Pakistani securities brokerage business

The brokerage business as a whole in Pakistan, however, does not appear to be particularly healthy. Brokerages make money when there is more trading on the stock exchange, and on that front, the data suggests the market is not particularly healthy.

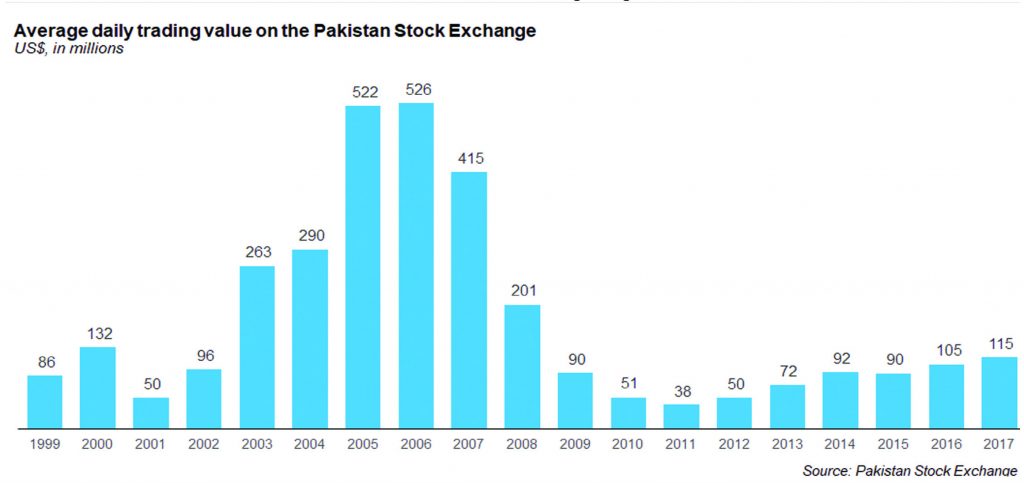

Volumes on the Pakistan Stock Exchange are currently languishing at roughly the same levels as in the late 1990 and early 2000s, and are down by about 80% compared to the peak reached in 2005 and 2006 under the freewheeling days of the Musharraf Administration.

The total value of trading on the PSX in 2017 was just over Rs3 trillion. That may sound like a lot of money, but brokerage fees in Pakistan tend to be very low.

In fact, most estimates suggest that brokerage fees in Pakistan amount to no more than 10 basis points (a basis point is one hundredth of 1%) of the total value of shares traded. Assuming two-sided commissions on every trade (both the buyer and seller have to pay their respective brokers), that puts the estimated total value of brokerage fees paid in Pakistan to just Rs6 billion ($57.5 million) in 2017.

There are 394 entities with trading rights entitlement certificates (TRECs), of whom the PSX estimates 228 are active in the brokerage business, who are all competing to earn commissions on trading activity that takes place on the stock exchange. That Rs6 billion in brokerage fee revenue has to be split among all 228 active brokerage firms.

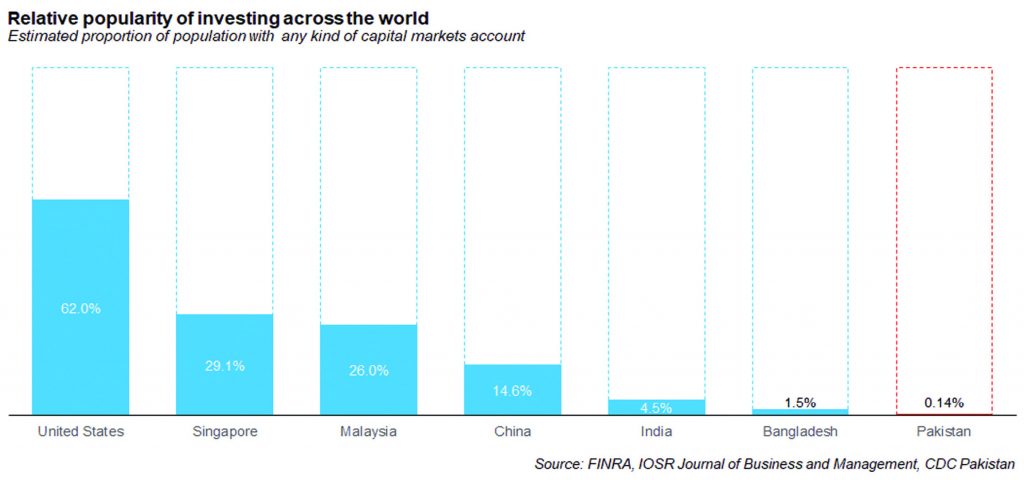

The reason for these low volumes and low brokerage fees is the fact that a very small proportion of Pakistanis are actually invested in the market at all. Just over 282,000 people in Pakistan have any kind of capital markets account, according to data from the Central Depository Company of Pakistan, or just 0.14% of the total population. That compares very poorly even against Bangladesh, where investor participation is at 1.5% of the population, and far behind India, where participation is at 4.5% of the total population.

And that number in Pakistan is barely keeping pace with population growth: since 2012, the total number of people with a capital markets account has only risen by an average growth rate of 4.4% per year, which is only marginally above Pakistan’s population growth rate of 2.4% per year. That means that the proportion of the population that is invested in the markets is rising very slowly from an already very low base.

This low level of investment in the Pakistani population is despite the fact that Pakistan’s capital markets are a highly lucrative place to invest, even after accounting for the fact that a substantial portion of trading activity that takes place in the market may involve illicit activities on the part of the brokers.

The benchmark KSE-100 index has risen by an average annual rate of 21.5% per year for the last 20 years. In absolute terms, this means that Rs1 million invested in a fund that matches the performance of the KSE-100 index 20 years ago would be around Rs49 million today. For foreign investors thinking about the effects of currency devaluation, the KSE-100 index has had an average annual return of 16.1% in US dollar terms during that same period. A foreign institutional investor who invested during that same period, using an index-tracking strategy, would have had $19.6 million in 2018 for every $1 million invested in 1998.

Caution in the markets

In such an environment, it makes sense that CLSA is entering Pakistan only through a minority investment and not through an outright acquisition of a brokerage firm. After all, the track record of foreign investment banks and securities brokerage firms in Pakistan has not entirely been pleasant.

In the early 1990s, when Pakistan began modernizing its capital markets and opening up to foreign investors under the first Nawaz Administration, a sizeable number of foreign firms entered the market, either through joint ventures or through outright purchase of a seat on the Karachi Stock Exchange.

Some of the American and larger European firms tended to prefer joint ventures and other types of partnerships. Merrill Lynch partnered with KASB Securities, Bear Stearns with Jahangir Siddiqui, UBS with Global Securities. Others preferred to buy a seat on the Karachi Stock Exchange in their own right, such as the European firm ING Barings, the Hong Kong-based Jardine Fleming. Virtually all of these firms left the market in the late 1990s or the early 2000s.

Jardine Fleming ended up selling its seat on the exchange to the American giant JP Morgan, which technically still owns the seat, though it has long since become dormant. Credit Suisse tried starting off small, with just a small research office in Karachi in 2008, but was unable to justify having a presence in the country and quietly close shop and left.

This is in sharp contrast to India, where a drive through some parts of Mumbai make it look like one is in the Indian outpost of Wall Street and the City of London: virtually anybody who is anybody in the capital markets has an office in India’s financial capital.