Jasim Haider will go down in history as the man who helped Pindi boys take pride in who there are like they never dared to before. Because the first thing that Rabeel Warraich told me was not that he is Pakistan’s first professional venture capitalist, nor that he graduated from MIT and worked as an investment banker at Morgan Stanley or the private equity direct investing arm of GIC, the sovereign wealth fund of Singapore, though all of these things are true and impressive credentials. No, the first thing he told me was that he was a proud Pindi boy.

Warraich’s story is not the kind we are used to reading about in Pakistan. A young man who grew up in a middle-class family – comfortable, but nowhere near wealthy – and went to good schools, did well academically and otherwise, went off to an elite higher education institution abroad, worked in high-paying professional jobs in London, and then returned to Pakistan as something the country has never seen before, but desperately needs: the founder of the nation’s first institutionalised venture capital firm.

On November 9, Warraich caused a stir by announcing that he and his partner – Austrian national and former investment banker Dr Bernhard Klemen – had raised $30 million from high net-worth individuals (HNWIs) and family offices for a venture capital fund dedicated to investing in Pakistani tech and tech-enabled startups.

While there is some global institutional venture capital investing in Pakistan, and Pakistani companies and wealthy individuals occasionally invest directly in local startups, an institutional fund dedicated solely to Pakistani companies has never been done before, particularly one that is designed to mimic the structure and institutionalised investing discipline of some of the world’s best venture capital funds.

Sarmayacar Ventures, as the new fund is named, builds upon the investing Warraich has already been doing alongside his friends and colleagues in Pakistani tech startups under the Sarmayacar brand name. In December 2016, Rabeel and the consortium of friends – most of whom were Pakistanis working in finance in Europe and the United States – announced that they would be investing $200,000 in Patari, a music streaming service based out of Lahore. That was followed by a $250,000 investment in ProCheck, a company that works to ensure the integrity of the pharmaceutical supply chain, announced in April 2017. And in February 2018, they invested $225,000 in a company called PublishEx, which allows app developers and digital content publishers to collect payments online and through cellular networks.

With these three investments, the Sarmayacar name was already known among Pakistan’s startups as a serious consortium of investors. The new fund takes that lead in Pakistani tech investing to the next level.

So how did this 33-year-old self-confessed Pindi boy pull this off? Well, it helps to be exceptionally intelligent and motivated.

Determined beginnings

Warraich was born to an upper-middle-class family in Rawalpindi in 1985. “My mother taught home economics at Federal Government Girls College in F-7/2 Islamabad for decades, and my father had a small travel agency in Islamabad,” he said, in an interview with Profit.

His father leveraged his travel agency business to take the family on extended vacations most years when Rabeel was growing up, often spending a month every year with relatives abroad, giving him and his siblings a more global outlook on life than their peers.

That more global outlook – and the ambition it bred in him – was not always appreciated by Rabeel’s peers. At age 13, having spent his early schooling years at St Mary’s Academy in Rawalpindi, his parents encouraged him to attend Cadet College Hasan Abdal. Needless to say, when you send a bunch of boys from traditional middle-class households all over Pakistan to a boarding school in Attock, things can get a little out of hand, and they can be a little unnerving for the faint of heart.

For Rabeel, the fateful day came during the first few days at Hasan Abdal, when the traditional hazing rituals began. A senior student came up to Rabeel and asked him what he wanted to do after he graduated from the Cadet College, and Rabeel, either out of naivete or gumption, replied: “I want to go to MIT.”

Now, if you said that line at Karachi Grammar School or Aitchison College (and a handful of other schools), you would get looks of admiration and respect or at least acknowledgement of the validity of that ambition. At Hasan Abdal, however, where the highest ambition of many of the students was a slot at the Pakistan Military Academy at Kakul, saying “MIT” was akin to putting a mark on one’s own back. Needless to say, Rabeel was not spared the worst of the hazing. “And for the entire time he was at Hasan Abdal, his nickname to all his classmates, and to everyone else, was ‘MIT’,” said Saad Duraiz, a management consultant at Deloitte in the United States, one of Rabeel’s oldest friends, and one of the initial consortium investors in Patari.

Some people might have let that experience get to them, but Rabeel did not let his ambition waver one bit. He particularly had a talent for physics, which kept honing and eventually it allowed him to gain admission into the university of his dreams: the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he enrolled in the autumn of 2004.

“My family is somewhat unusual in that even me graduating from MIT still makes me the black sheep of the family,” says Warraich. “My sister has a postdoc in neurobiology from Stanford University and currently works at a biotech startup in Silicon Valley, and my brother is a philosopher and photojournalist. I stand out as the capitalist in the family.”

Following his graduation from MIT in 2008 (he started before the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy), Warraich began working as an investment banker at Morgan Stanley in London, working with the mergers and acquisitions group, typically considered the most prestigious even within the already rarified world of high finance. That stint as an M&A banker allowed him to get a job in 2011 at GIC, a $359 billion sovereign wealth fund owned by the Government of Singapore to manage and invest their foreign exchange reserves.

It was at GIC that Warraich got a taste of investing in private companies, although his job typically involved companies that were much further along their lifecycle than startups.

GIC and the investing bug

One of Rabeel Warraich’s defining characteristics is that he is a workaholic. Investment banking is an industry that is notorious for its long working hours (100-hour workweeks are completely normal), but even by investment banker standards, Rabeel is a workaholic, frequently working 20-22 hours a day, often to the point of collapsing out of exhaustion.

Why is that relevant? Because when he moved to the relatively more relaxed work environment of private equity at GIC (only 12 hours a day!), he began exploring other interests, specifically investing in high growth startups.

Warraich began exploring how to begin investing in private companies and buy meaningful amounts of shares in some of the most promising startups in the world. His job at GIC had taught him how to evaluate companies from an investor’s perspective, and he applied that to his own personal investing strategy as well. Yet while he was a well-compensated professional, he did not yet have the kind of capital that would allow him to purchase a large enough block of shares on his own, and so he put together his first investing consortium of likeminded young professionals working in the world of finance who were also interested in investing in startups.

Their first investment was in Spotify, the Sweden-based global music streaming app, and they bought a block of shares from former employees of the company through a platform called Microventures that allows for the trading of shares in private companies between accredited investors.

But as interesting as the experience of investing in pre-initial public offering (IPO) shares of Spotify was, Warraich was obsessed with trying to find a way to invest in Pakistan. Indeed, when he was interviewing for the job at GIC, he said in his interview: “If in ten years, I am not back in Pakistan, something has gone wrong.”

And thus began the long quest for investing in Pakistani startups, which saw Warraich spending years developing an understanding of the market before he was finally ready to take the plunge.

Waiting on the market to mature

While some of Pakistan’s leading startups have been around for a long time (Zameen.com was founded in 2006), the broader culture of entrepreneurship in Pakistan did not take off until 2012 or so, largely in anticipation of the boom on mobile internet connectivity that would come with the auctions of 3G and 4G spectrum to the cellular telecommunications companies.

When those licences were actually auctioned off in April 2014, Pakistan’s entrepreneurial cycle began to take off. Soon thereafter, Rabeel Warraich began his foray into understanding the world of Pakistani startups.

“In 2015, I started exploring early-stage businesses in Pakistan,” said Warraich. “I would spend every single vacation in Pakistan. I would go and sit in the English Tea House and have 30-45 minute meetings with entrepreneurs and others to learn about Pakistan’s startup ecosystem. I used to send my father-in-law a list of names before every trip, and he would help me arrange meetings with people I wanted to see on my Pakistan trips.”

“It was exhausting to do this. My colleagues started noticing that I would be more tired after my vacations than before them.”

Over the course of that year, he met with dozens of entrepreneurs and other professionals and learnt as much as he could about Pakistan’s startup environment. Meanwhile, he was putting together one more consortium of likeminded friends who would be willing to put together investments in Pakistani startups should he find one that he liked.

It was during one of these visits that he heard about Patari.

The Patari investment

It was August 2016, and Warraich was towards the end of his visit to Pakistan when he heard about Patari, a music streaming app focused on Pakistani content.

Just two days before he was about to leave Rawalpindi to go back to London, Warraich sent an e-mail at 11 pm to Ahmer Naqvi, then the chief operating officer (COO) of Patari, asking if there was a chance they might be able to meet him. He did not think much of it. Most people in Pakistan are not very prompt about responding to e-mails and this was not Warraich’s most enthusiastic outreach effort to begin with.

But Naqvi wrote back almost immediately saying: “We’ll see you tomorrow morning in Islamabad.”

It turned out, however, that Naqvi had been optimistic about the ability of the Patari team to be able to get to Islamabad from Lahore by the morning. They were not able to get to Islamabad until late that evening.

At 7 pm, that day in August, Warraich made his way to Chaaye Khana in F-6 Markaz Islamabad with his brother, brother-in-law, and one of his closest friends, where the four of them met with the five core members of Patari’s team. What followed was a conversation that absolutely mesmerised Warraich and his team. There was an almost immediate chemistry between the Patari team and Warraich’s group.

Over the next five hours, they sat across from each other, getting to know one another, talking about their perspectives about Pakistan’s tech entrepreneurship ecosystem, the Patari team’s vision for where to take the company, and Warraich’s vision for wanting to invest in Pakistani startups. At midnight, they had to be asked to leave Chaaye Khana because it was closing down (because Islamabad is not a real city… sorry, old Karachiite habits die hard). And so, they moved over to Hotspot, to continue the conversation.

This was the kind of conversation that one reads about in the legendary stories of venture capitalists meeting budding entrepreneurs. This was how it went when Arthur Rock met Steve Jobs, or when Masayoshi Son met Jack Ma.

There was just one problem: Patari needed $200,000 in growth capital, and Warraich could only put together $120,000 between himself and his group of friends. He wracked his brains to think about what he could do, where he could get the money, and who he could call to put together the financing package. And that is when he called an old Morgan Stanley friend: Bernhard Klemen.

Warraich called Klemen that day from Rawalpindi, explaining that he had found a Pakistani startup that he wanted to invest in and needed to raise an additional $80,000. Klemen said, “yes, count me in.” To which Warraich responded: “That sounds great. Now would you like to know what the company does?”

“It’s a reflection of the high level of trust that Bernhard and I have with each other,” said Warraich, reflecting on that conversation. “We trust each other’s judgment about investments, and in each other’s integrity.”

Having thus secured the funding, Warraich then began putting together the paperwork that would govern not just his relationship with his co-investors, but also the relationship between what was now being called Sarmayacar and the companies it was investing in.

On December 30, 2016, amid much fanfare in Lahore at the headquarters of the Punjab Information Technology Board (PITB), Sarmayacar signed its investment agreement with Patari. Sarmayacar would invest $200,000 into Patari, and would get a seat on its board of directors. At age 31, Rabeel Warraich became chairman of the board of directors of a company in which he had led a round of venture capital investment.

The growth of Sarmayacar

The buzz created by the Patari investment meant that Warraich’s phone blew up. “When you start waving cash around, people will obviously want to talk to you to get money. But surprisingly, we also started getting calls from people who wanted to invest their money with us,” he said. “Many of them were Pakistani professionals living and working outside the country who saw us as a curated equity crowdfunding platform. The reality is that it wasn’t that. And so we did not take people up on their offers.”

For the next few months, however, Warraich kept it strictly focused on his own group of friends. But it was becoming more and more of a fulltime job on its own.

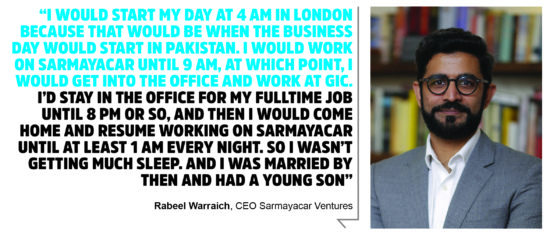

“I would start my day at 4 am in London because that would be when the business day would start in Pakistan. I would work on Sarmayacar until 9 am, at which point, I would get into the office and work at GIC. I’d stay in the office for my fulltime job until 8 pm or so, and then I would come home and resume working on Sarmayacar until at least 1 am every night. So I wasn’t getting much sleep. And I was married by then and had a young son.”

During the month of January 2017, Warraich spoke to 100 companies about possible investments. Two things became clear. First, that he wanted his second investment to be in ProCheck, the company that works on pharmaceutical supply chain integrity. And secondly, that managing investments in Pakistani startups could become a viable full-time career, though if wanted to be any good at it (and not be quite so absent from his family life), he would have to move back to Pakistan.

It was time to move back home.

The move back to Pakistan, and the launch of the fund

Even for someone as dedicated to Pakistan as Warraich, the decision to move back is not easy. He and his wife had spent considerable time in London, and bought a home there. And while Warraich never revealed how much his salary was, people in his position at his firm routinely make north of $500,000 a year. Giving that up is a huge challenge.

“We had a very comfortable life in London. We bought a house, we could buy whatever we wanted, and had a lifestyle that I could never match in Pakistan. Every year, I was making more, which meant that it was harder to come back. The honey trap, it’s called. But on the decision to move back, I owe the clarity of thought to my wife. She would ask me: ‘Will you regret it if you don’t move back?’ And my answer was always yes.”

By May 2017, Warraich made the decision: he was moving back home to Pakistan.

He handed in his notice to GIC and said that he would stay on for another three months to wind up his work. In the meantime, he started travelling all over the world to begin raising money for the fund. As his partner, he enlisted the help of his friend Bernhard Klemen, who at the time was working for JPMorgan in Austria.

Klemen had also been making VC investments on the side, though unlike Warraich, he had already hit some big home runs, including one investments where his unrealised capital gains were already 150 times his initial investment. Klemen was keen to enter the venture capital space more formally and on a full-time basis but realised that he needed differentiation in order to succeed.

“He could either launch the 30th venture capital fund focused on Central Europe, or he could help launch the first one dedicated to Pakistan. So I started taking him with me to Pakistan to meet entrepreneurs and investors,” said Warraich.

As their anchor investor, Klemen was able to get Jan Bolz, the 57-year-old founder and CEO of Tipico Sportwetten, a European sports betting operator. Klemen had helped manage the sale of that company to European private equity giant CVC, in addition to having previously co-invested with Bolz in some of his venture capital investments, including the one that saw the massive capital gains. So Klemen was coming to Bolz at a time when he had just made him a lot of money, and established his credibility as an investment advisor.

After a five-day trip to Pakistan to get Bolz comfortable with the concept of investing in Pakistan, Bolz committed to putting in $2.5 million in the fund in November 2017. That anchor investment meant that Warraich and Klemen were off to the races.

Next began a mad dash around the world by Warraich and Klemen as they darted to every major financial center in the world to meet prospective investors, all while Warraich was still helping manage the permanent move of his family from London to Lahore.

“I have done day trips to Singapore, and day trips from Singapore to Hong Kong,” he said.

And it did not help that he was trying to raise capital at a time when Abraaj Capital, then the largest alternative investment manager operated by a Pakistan CEO, was imploding. It was the worst possible time to be a Pakistani professional seeking to raise capital in a blind pool of funds to invest in Pakistani startups, selling essentially nothing but your own personal credibility and the prospects of growth in Pakistan’s economy.

Some European family offices and high net-worth individuals (HNWIs) invested in the fund, but the bulk came from Pakistani HNWIs based outside the country. One hedge fund manager in New York who invested in Sarmayacar told Warraich: “If I was 20 years younger, I wouldn’t be investing in this fund. I would pack up and move myself to do what you are doing.”

He also tapped some wealthier Pakistani families that wanted to invest in his fund, including one of the wealthiest families in Lahore, and another family in Karachi. He also turned down some investors whom he felt would not be amenable to his desire to keep everything transparent and above board.

By mid-2018, Warraich had enough commitments to close the fund at $30 million, which formally closed on October 29 of this year.

The structure of the fund at the strategy

Sarmayacar Ventures has a structure that is very common in the United States and Europe, but unprecedented in Pakistan. The company has incorporated both the general partner that manages the fund (Warraich and Klemen) and the limited partnership that actually holds its investors’ funds in the Netherlands, owing to its flexible corporate structure, favourable tax treatments, and the fact that Pakistani lawyers and accountants are familiar with Dutch law because many multinational companies operate their Pakistani subsidiaries using holding companies in the Netherlands.

The fee structure is the standard 2/20: a 2% annual management fee on the amount of funds invested, and 20% of the profits earned above a specified hurdle internal rate of return. The hurdle rate is 4%.

The firm’s investment strategy involves investing in startups that offer scalable consumer-facing business models, ideally concepts that work in developed markets and have been localised for the Pakistani market. In addition, they are willing to consider companies that sell outsourced services to developed markets, provided they can demonstrate a cost advantage.

They are also not interested in investing in companies that do not already generate at least some revenue.

The investment committee consists entirely of just Warraich and Klemen, though they are willing to allow their investors to sit on the boards of the companies that they will be investing in so that there is transparency in how the money is being managed.

But all of these rules and protocols still do not account for the curveballs that life can throw.

The Bajaness problem

In April 2018, in the midst of Sarmayacar’s fundraising drive, there was a bombshell coming out of the nascent firm’s signature investment: Patari founder and CEO Khalid Bajwa was credibly accused of sexual harassment by a woman he knew outside the company.

Despite the advances made by the Me Too movement across the world, Pakistan had not yet seen a man in the corporate sector be held accountable for his actions. This was Warraich’s moment to decide: which direction would he take this. The precedent he would set would affect not just his own firm’s investment, but also potentially impact the broader Pakistani startup culture.

Warraich chose to be decisive: as chairman of the Patari board of directors, he had the power to fire Bajwa as CEO and he took it. Bajwa was summarily removed from his position at the company he founded, and Warraich asked then-COO Ahmer Naqvi to step in as interim CEO while beginning the search for a permanent successor to Bajwa. (Naqvi later resigned in July, causing Warraich to step in as interim CEO).

Had he ended his actions there, it could have been argued that Warraich had done more than most investors might have done in his shoes, but Warraich went one step further: he asked an investor and lawyer (both women) to conduct a “cultural audit” of Patari, to assess whether the scale of the problem extended to Bajwa’s behavior at the company, over and above what had been revealed by the allegations against Bajwa.

That audit revealed a corporate culture beset with problems, and several female employees stating that they felt uncomfortable around the CEO.

Firing Bajwa might have helped solve the problem, though there was one big issue: he was still a major shareholder and a member of the board of directors. This is where Warraich’s foresight in having a solid legal structure and legal agreements in place came in handy: Sarmayacar has been able to leverage the terms of its agreements to remove Bajwa not just from his position as CEO but also from its board of directors, his aborted attempt at returning to his position in July notwithstanding.

In the meantime, the hunt for Bajwa’s successor continues.

While he juggles the role of serving as interim CEO of Patari while also setting up Sarmayacar Ventures, Warraich can at least say one thing: he has already demonstrated the kind of “adult supervision” over his portfolio companies that sophisticated investors would want to see in the kind of money managers they entrust their money with.

Corrections and amplifications: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the initial allegations against Khalid Bajwa were made by a former Patari employee. That was not the case. They were made by a woman he knew outside of the company. The article also stated that Warraich immediately took over as interim CEO. That is also not correct. Ahmer Naqvi had initially stepped in as interim CEO and Warraich only stepped in after Naqvi resigned. The article also stated that a law firm was hired for a cultural audit. That is not correct. The cultural audit was conducted an investor and a lawyer (both women) and was conducted on a pro-bono basis.

The whole firing ‘Bajwa’ episode and stealing his company smells of conspiracy.

Punish the guy for harassing a female employee, but don’t take his life’s creation away from him?

He should be careful risking all his life’s creation then. And risk it all for what? A bunch of feet pictures? Times have changed!

It smells of no conspiracy. I personally knew Bajwa from before he founded Patari. The guy was a creep.

Nice thoughts and your working strength looks you can stir the system.

I can be a client in your pursue for your venture in the field of much need hydro power.

Comments are closed.