What would you say if someone were to tell you that in the heart of Lahore’s posh DHA, there was standing ready a group of some 60-odd young professionals brimming to storm corporate Pakistan? That over the past two years, these few dozen young men and women have undergone gladiatorial training in the discipline of business, coming out chiseled with a wide range of skills, and ready to take on the world.

This is what the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) would have you believe about their flagship MBA programme, and how it takes cub professionals full of potential, and turns them into corporate wolves.

At any given time, LUMS houses thousands of students. By far the largest component of this student body are undergraduates, over a thousand of whom joined the university’s ranks in just the latest admission cycle as part of the class of 2022. Along with these are a smattering of doctoral and graduate studies candidates, all coming together in the famed LUMS ecosystem. In the middle of this vast array of students from all over Pakistan pursuing different levels and degrees of education, the MBA class stands out. This year, there are only 62 of them that will graduate the intense two-year programme.

The number seems paltry. The MBA programme is what made LUMS, after all. The LUMS business school, the Suleman Dawood School of Business (SDSB), first opened its doors to an MBA batch in 1986, when the university had just been conceived. But in the push to become Pakistan’s leading undergraduate institution, the MBA seems to have taken a back seat at LUMS.

With only an MBA degree and a few years of experience to show for, how much exactly could 62 people do to shake up the corporate world? According to the people at LUMS, a whole lot more than one would imagine.

The small batch size is a question of design, not capability they say – only the best get into LUMS, so that by the time they leave, they are the top of the line – being wooed by the market instead of desperately trying to find a place in the world of business.

Yet how relevant is a LUMS MBA anymore, and how true are the claims that LUMS makes? What sets it apart from the many other MBA programmes in the country? With how much it costs and the rigour of the admission process, would a person not be better off spending a little more and going to a foreign business school? What opportunities does it offer its graduates, and more importantly, what do its graduates offer the world? Profit takes a look.

Pakistan’s Harvard and more

“One could say that LUMS is the Harvard of Pakistan, but actually that would be undermining the stature of LUMS,” says Dr Alnoor Bhimani, the recently appointed honorary dean of the Suleman Dawood School of Business (SDSB).

This is a somewhat unusual statement, to say the least. The vain, self-important, Harvard-LUMS parallel is one usually drawn by students, not deans. Nearly a thousand MBA grads are released into the corporate world by Harvard every year while LUMS only produces a handful, which begs the question – where’s the comparison?

But in the same candour, Bhimani follows up with a surprisingly sound argument. For starters, Harvard has competitors, and with Wharton [and Stanford, Chicago, and Columbia] still around, it is not indisputably the best business programme in the United States.

Secondly, according to Bhimani, as an institution, LUMS has the power to affect change like no other university on the planet. LUMS, in Pakistan, supersedes the stature of Harvard simply because it is such a small organisation. With some 4,000 plus students and only 60-65 coming in for the MBA programme each year in a country with a population of 210 million, the impact is absolutely massive.

“My view is that whatever we do here at LUMS in terms of the education we provide or in terms of some of the changes that we will talk about later on, I think those are kind of echoed and mirrored by other institutions here” says Dr Bhimani. “Changes that Harvard makes have minimal impact in the US. Changes that LUMS makes in Pakistan have a massive impact in a circular sort of sense.”

As the leading business school in Pakistan, changes that LUMS makes are quickly emulated or mirrored by other institutions. Thus, LUMS stands in a unique position, where its actions affect more than just its students.

The MBAs that leave LUMS will not only be hot on the market after graduating but will have left LUMS with a range of abilities that they can use to make a difference. For the graduating class, their LUMS education has put them in a sweet spot. But who are these graduates? Where do they come from and what have they done to find themselves in this privileged position? To be graduating with an MBA from LUMS, and in turn poised for the very best.

The best of the best

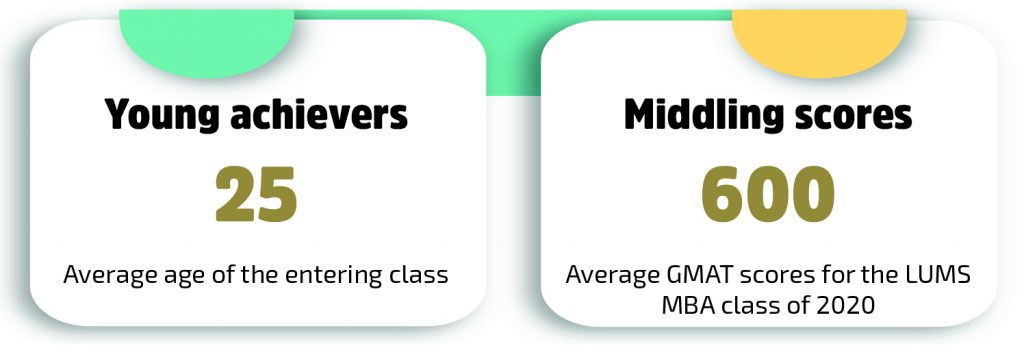

For LUMS, it clearly is a case of selecting the best of the best. With an average age of 25, the LUMS MBA is mostly taken up by engineers, more than 50% of whom make up the entire batch. With an average work experience of two-and-a-half years, and a GMAT score of 600, the people admitted to the MBA programme are the academic elite of Pakistan. [Editor’s Note: That a GMAT score of 600 gets you counted as the academic elite of Pakistan is rather sad for Pakistan.]

Read more: Meet the best of LUMS MBA Class of 2019

And after their two years at LUMS, they are looking at better prospects than they could have before. Many of the graduating class have already received job offers, and others are either weighing their options or have already accepted employment somewhere.

Return on investment – is it worth it?

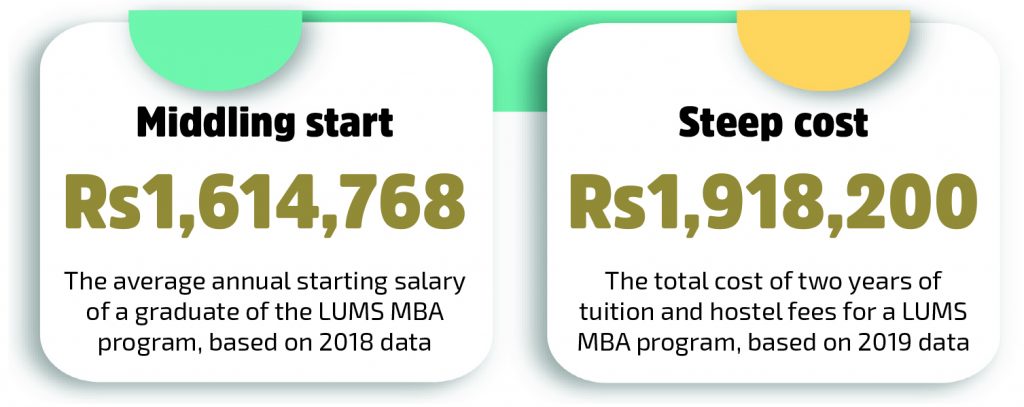

But the LUMS MBA comes at a cost, and with a price tag of more than Rs2 million, prospective MBAs have a lot of introspection to do about what their return on investment will be. The average salary that the batch of 2019 was getting before joining the MBA programme was around Rs 100,000. Their expectations for what they will get after graduating is not much higher, ranging from around the same amount up to a maximum expectation of Rs 200,000.

With the salary forgone in the two years taken for the MBA added to the cost of the MBA, there seems to be a long road ahead until there is a basic return on investment. This also forces one to wonder, why not just spend the extra money and go to a business school in the US?

LUMS does not offer any significant financial aid to its MBA applicants, and the only scholarship it offers is for anyone that manages a score of more than 700 on the GMAT – the American standardised test that is the basis for admission into LUMS. For applicants with such outstanding scores, one thinks whether or not they would be better off shooting for aid at an American school rather than being contented with LUMS.

“The GMAT score is a small element of what we consider. It is just one small variable. One small part of the equation. You know if somebody came in with a GMAT score of 780, and said well I want you to finance the whole thing, I would say let’s look at your other abilities before we do that,” explains Dr Bhimani on the LUMS scholarship question.

He also claims that just a score of 780 is unlikely to mean getting a scholarship at Harvard or Stanford, and the only schools that offer such scholarships are the ones looking to increase their GMAT profiles – an approach LUMS wants to stay away from. “Besides, we are doing very well as far as GMAT scores go.”

On the question of return on investment, Dr Bhimani says that one must look at the whole impact of the education, rather than just in purely economic terms. “The return on LUMS is very high, simply because a starting salary translates into huge number of possibilities. A wide alumni network. And with the AACSB now we’ll be interacting with other business schools” he says. “The pure focus on salaries vs tuition fee captures a very small element of what we offer here.”

Indeed, for a lot of the people at LUMS, it isn’t just about the monetary return that an MBA from LUMS gives them. “I wanted to join my family’s business and realised that the networking potential of graduating from an esteemed institution can help me stand out from the rest,” Qasim Asad tells Profit. For him, LUMS was not a question of monetary return on investment, but of making the right connections.

“Any company you go to, any significant work you have to deal with in the business world, and you will find someone from LUMS there that will be of service to you, that is how the alumni network works,” he explains. “The networking opportunities at LUMS and its brand name made me choose the university. But it has provided me with the knowledge about best practices being used around the world today.”

Similarly, for Jawad Nasir, his offers from Brown, USC, and Rochester all paled in comparison to LUMS simply because of the vast alumni network that the university has in Pakistan, and many other parts of the world. “The LUMS alumni network is second to none, present all over the world. I had other offers, but nothing can beat the return on investment that the LUMS network gives you,” he said.

For others, it was not just the network but the weight that comes with the LUMS brand name. Employers in Pakistan of all sorts will give first preference to graduates from LUMS. Furqan Tariq says that in addition to the LUMS brand, having an MBA from LUMS provides a stamp of approval that is seen by corporations as something worthy of their attention.

The case study methodology

But what is it about the LUMS MBA that commands such respect from corporations and employers? Why do the graduates of this programme pique such interest from the market? There are countless other MBA degrees on offer in the country, including from places such as IBA, but none are as prestigious or sought after as LUMS.

For many of the students at LUMS, at the core of what makes its MBA programme so special is the case study methodology. Mohsin Obaid, the LSE topper who left Nestle for LUMS, says that he did not have to look anywhere else because there was nothing beyond the LUMS’ case study method. “I did not apply for any other program because LUMS is by far the best business school of Pakistan. Their case study methodology and experiential learning component makes the program practical in approach and helps speed up learning,” he says.

There are different takes, of course. Furqan, for example, believes that it is the ‘DR culture’ that sets LUMS apart from other institutions, but even this is an extension of the larger ‘LUMS way’ that is geared around case studies. “The usual answer is case study but I would say the DR (discussion room) culture – it’s closely linked to cases but the DRs play a role in bringing together people and inculcating that culture of working together to achieve goals by discussing and listening. It can be tough but it mimics the work environment. And for me it was a source of friendships I will treasure for the rest of my life.”

For LUMS, the case study is a defining feature. During the two years at LUMS, students work on over 500 cases, and once a case is presented in class, the students become the decision makers in various business management scenarios.

They are divided into study groups who work in a Discussion Room prior to joining their peers in the classroom. By the time they return, they are expected to have analysed the situation according to the given limited information, identified problems and issues, and defined alternatives amongst the study group. After this they are supposed to bring thought framework to the class for further exchange of ideas on a larger scale led by the professor, and then draw conclusions and recommend viable solutions.

These rapid, action packed, often tense and high intensity exercises give students the ability to think on their feet and become risk takers and gain crucial practical experience with no real world consequences but their own grades.

To say that the case study method was the foundation on which LUMS was established would not be inaccurate. “The way this school was founded was drawn on lessons from the University of Western Ontario and Harvard University which used the case study approach. And alliances were created and these universities came in and they set up a certain set of principles on which we have operated. And we have maintained that and today in Asia we have the biggest bank of case studies anywhere” Dr Bhimani explains.

With more than 600 cases in their reserves, LUMS does indeed boast the largest bank of case studies in all of Asia. But for all the hype and the glowing testimonials, many of the students grumbled off the record that the case study method, while brilliant, was not as up to date as it could be, and that there remained room for improvement. Off-the record, some of the more seasoned faculty also felt that the case study methodology was losing its importance in LUMS.

But if the significance of the case study is waning, does that mean LUMS is losing its essence? Is the university taking for granted the very thing that gave it its edge? For Mishaal Mubasher, the earlier mentioned English undergrad and LGS teacher trying to change her career trajectory, not only was the case study method is one of the things that brought her to LUMS, and sitting through lectures from professors such as Dr Arif Rana, Dr Ehsan and Dr Jamshed, were some of the best experiences of her life. Over the past few years, LUMS has lost some these veteran instructors. Dr Imran Ali, and Arif Rana, – longstanding pillars of the LUMS faculty that were integral to discovering the formula that has made LUMS so successful, and stalwarts of the case study methodology. Dr Ehsan ul Haque, another giant of the SDSB faculty and the case study method, also parted ways with LUMS. While he has been rehired, it seems that his importance has waned, with fewer courses on his plate and a more honourary role at the university. Dr Jamshed, while still an active SDSB legend, has also been taking some heat from campus activists and the university’s extra-curricular life.

Some also believe that while LUMS is the best Pakistan has to offer and has seen a meteoric rise, it seems to have become stagnant. The university has achieved great heights, and the credit for that goes to these founding professors and the university. But there was a time when LUMS was embroiled in a fierce competition with IBA, something that kept pushing it to improve. But ever since IBA has lost much of its vigour, LUMS too seems to have lost some of its former hunger to be the best. Could this be complacency? LUMS might be the best in Pakistan, but could its current position have more to do with the failure of its rivals than with its own success?

Not only has LUMS lost these old war-horses, their replacements have been of a different ilk. Dr Bihamani claims that there has been an influx of a huge number of PhDs coming back to the country in the past decade, and this has meant LUMS has had to change its orientation.

“We wanted to expand management education, so we hired a lot of these PhDs. In order to attract PhDs who had chosen an academic career path, they of course need to publish, so to carry on an intense focus on teaching would not have met their needs. From then on, teaching counted for a lot, but scholars wanted to build their research profiles, and so the mood here began to change, and with that there was a change in the criteria for promotions. Since then, SDSB has instituted a regime whereby you could actually thrive by publishing in top journals.”

With this introduction of research oriented faculty and exodus of the builders of the LUMS methodology, it is easy enough to wonder whether the case study methodology was facing a slow death. Profit set to find out how many case studies LUMS had produced in recent years – and whether the number of cases had fallen since the new research oriented hirings in the faculty. Despite multiple attempts to get these numbers, and repeated assurances from LUMS, no figures were provided, making one wonder just how lax the university had gotten in this department.

Dr Bhimani also only gave cursory answers, unable to deny the shift in focus, but also trying to defend it at the same time. “I think at a time to teach cases you need to have outstanding teachers. We are actually sort of the beneficiaries of the bad fortune of not having been able to attract intensely research oriented scholars. It was pretty much outstanding teachers who were then taught how to teach using cases and that has remained our forte for a very long period of time.”

And as the Dean explains, LUMS is just trying to keep up with the times, because even the case study method has its set-backs. According to him, the case study method is almost exclusively geared towards providing managerial instruction – something that LUMS was founded on. But now, the business school is looking towards finding its footing in more theoretical ground as well.

“The secret formula changes, it never remains the same. The case study is core to SDSB, but it cannot be the only source of sustenance for managerial education. All the case-based schools are also increasing the range of teaching approaches” Bhimani tells Profit.

The case study method might be what LUMS was built on and still is its primary attraction, but it is not all that LUMS has to offer as it tries to evolve with the times. The most recent example is their newfound focus on experiential learning, in which students are given the opportunity to apply their academic learning in a real business context outside of their day-to-day learning environment. Another recent innovation is the global module, the idea of which is to send students abroad.

“We have done it in Silicon Valley, for some time where they go to Google, they go to Facebook and they might attend some courses at Berkeley and they come back really charged because they have had a certain amount of LUMS MBA base education and then they are seeing very different things which to that,” the dean explains. “So, they come back with a fire in their belly for what it is that they can do. Pakistan desperately needs to generate greater entrepreneurial drive. That module exposes them to possibilities that they just do not see here.”

The death of entrepreneurship?

But what do these techniques breed? For sure, LUMS is providing its MBAs with priceless managerial knowledge, skills and most importantly experience, but is that all LUMS is producing? Troops upon troops of managers to handle already established businesses? With job offers knocking at the doors of about-to-graduate MBAs, many of these students simply cannot pass up the opportunity for jobs in big companies such as McKinsey.

Most of the batch we interviewed said that their dream job was to one day have their own company, but none of them wanted to work on this dream right off the bat. Work for five years in this industry and make enough to strike out on your own. Have a business at the end of this many years. Open up a small thing on the side and see how it goes before devoting yourself to it fully.

In such bright young minds, there was no doubt alive and roaring the entrepreneurial fire – but had their two years at LUMS trained them to be prudent managers and drained them of the daredevil instincts of entrepreneurs?

“My view is that you are right to a great degree” Dr Bhimani admits. “LUMS has been seen as a funnel into a great employment situations. Low hanging fruits are what graduates often aim for, and jobs provide a good income right away.”

“So even if you have entrepreneurial intentions when you come in, you say thanks be to God I have got an offer from McKinsey or Bain. You think, I cannot turn down the salary that they are offering, so maybe I will come back to entrepreneurship one day and maybe such individuals do.”

But the problem is one that LUMS intends on tackling head on. They already have one of the five National Incubation Centers (NIC) stationed on campus, which is all set and running, as well as a huge entrepreneurship center that the university wants to set-up. The scale of this center would be large enough that the issue they are facing for this project is a lack of space.

“My view is that ultimately entrepreneurship powers the economy of any nation and there is not enough of it here. We are entering a world where technology allows us to have very low barriers to entry in startups,” the dean explains.

“The Pakistanis that I meet who are entrepreneurially motivated have ideas that you don’t see anywhere else because they are a product of their context. There are things about Pakistan which are so unique that I cannot help but think that we are going to see entrepreneurs go a very, very long way, but it won’t happen unless we have that educational infrastructure that focuses on entrepreneurship.”

The place to be?

For a young professional with nothing but ambition and a few years of experience, making the decision to pursue an MBA has one goal – improving your life. As most of the MBA candidates we spoke to said, whether it was for a career shift or to have better opportunities through networking and practical knowledge and skills, the MBA was their way to step up in the world.

For someone making the decision to do an MBA, the natural goal might be looking towards Harvard and INSEAD – schools that command respect and grant prestige. Yet for anyone wanting to make their way in Pakistan, LUMS is not only definitely on the list, but might even be the best bet.

“LUMS basically provides a gateway to understanding everything about business in Pakistan as well as infusing the education provided here with ideas that come from the globe over. that is uncontested,” Bhimani says.

Despite him having some vested interest as the Dean of SDSB, one feels that he speaks in earnest. LUMS gives corporate hopefuls an insight into the world of Pakistani business that no foreign degree could ever impart. It is, quite simply, the best training camp for people wanting to make it in corporate Pakistan. And as Bhimani puts it, “LUMS is where you need to be.”

Just recently, LUMS hit a new milestone when it was accredited by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB), one of only 850 schools globally to be accredited – an impressive achievement to say the least, but one that comes from decades of commitment to a long-standing methodology. The accreditation reflects the history of LUMS – it was first proposed nearly a decade ago, around the time when LUMS was first making its shift towards a research oriented faculty. A formal application to the AACSB was made six years ago. LUMS is beyond any doubt the best business education Pakistan has to offer, and what this accreditation proves is that LUMS also has the muscle to be an institution of international standing. What is to be seen is whether the current model is sustainable. The LUMS that applied to the AACSB was clearly a university worth the label, but when the Association’s reviewers inevitably roll in five years later, will LUMS still be at the same perch, or will it have to go through the embarrassing spectacle of being stripped of the accreditation? “Very major schools have seen their AACSB accreditation come under threat. So it has happened before. Excellence has to be continually engendered” says Dr Bihamani. The past may have gotten it where it is now, but LUMS has some introspection to do if it wants to maintain its stature.

LUMS is the best MBA institution for marketing and other social science fields like HR management etc. But in no way it can compete with IBA Finance grads. The quality of finance grads from LUMS is, at best, average. I’ve interviewed many LUMS grads (and supervised some) and all they are good at is their communication abilities.

There is less trend even among LUMS grads to pursue finance degrees as they get paid so well already by doing the easy courses in marketing and management. That’s why you can see that there is hardly someone who after completing his MBA in Finance from LUMS would go after CFA charter. For one, he/she would already be getting a job on the basis of LUMS tag so there’s no need. But in case they attempt for CFA tests, it won’t be easy for them to pass and get a charter. If you want proof, you can just see how many CFA charterholders are from LUMS vis a vis those from IBA. You’d be thoroughly surprised.

You forgot to mention… This LUMS grads darling trend has greatly reduce now among employers….basically because of their non commitment and “i know everything* behaviour..

Lums is owned by Indurstralists. They have a good campus in a posh area. Lums Students come from rich families. It is just over rated.

yes quality of IBA students is a lot better as they come from all over Pakistan only on the basis of merit.

Very true. IBA is more inclusive.

Go take your jealousy somewhere else.

This is a paid advert from LUMS, it is sponsored content ! PakistanToday should highlight that as do all newspapers do, so that readers are not fooled into thinking this is an actual news report. Sadly it shows the desperation LUMS is now having trying to attract students. While it offers good education by Pakistan standards it still remains a place where you are likely to find rich kids rather then any other variety.

Comments are closed.