For over a decade now, Hum TV has been one of the most watched entertainment television channels in Pakistan, consistently ranking at number one or number two in the ratings. It has produced iconic Pakistani television dramas such as Humsafar – the show that catapulted the careers of Mahira Khan and Fawad Khan to international stardom – and along the way reinvigorated the art of Pakistani television entertainment.

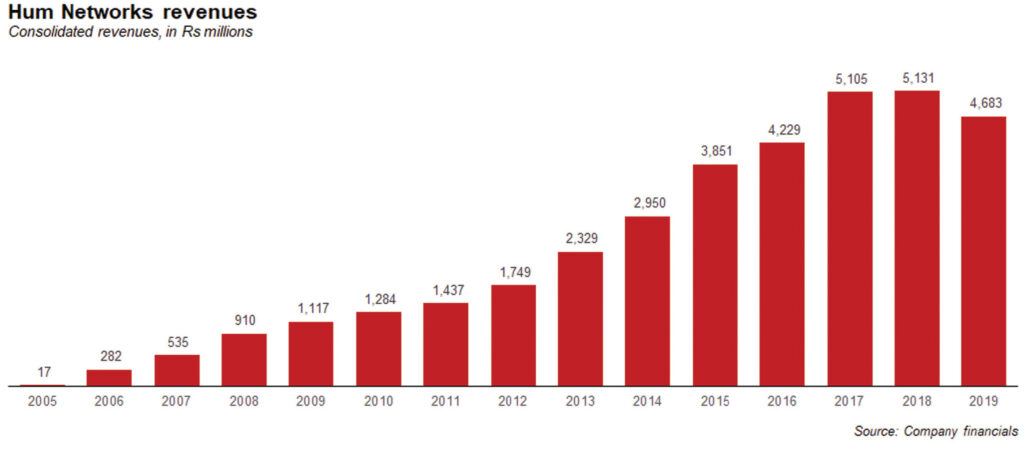

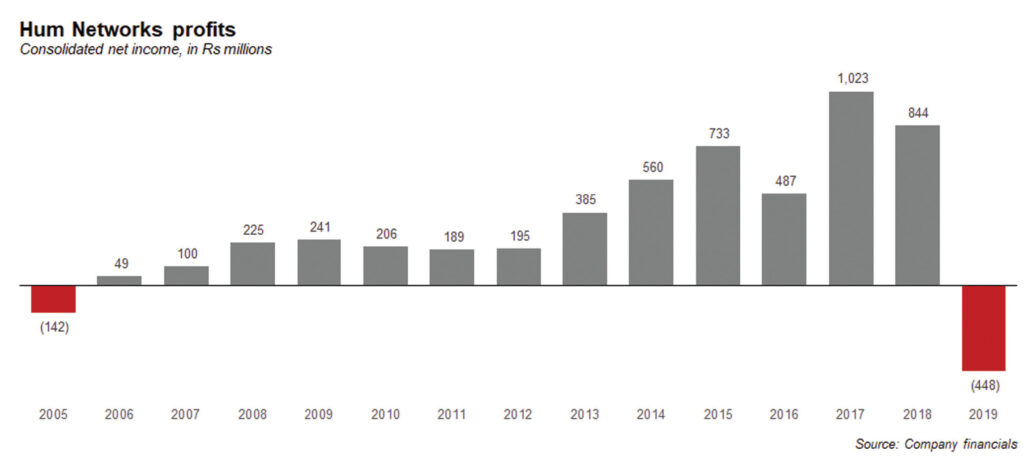

And although earnings have sagged lately, along with those of the rest of the industry, its parent company Hum Networks is one of the largest, and most profitable, media companies in the country, earning consolidated revenues of Rs4.7 billion in the 12-month period ending March 31, 2019, the latest for which financial data is available, down 8.7% from a peak of Rs5.1 billion for the financial year ending June 30, 2019.

The company commands a respectable 10% of the advertising revenue made available to television channels, according to estimates published in Aurora, the advertising magazine. That market share number puts it neck-and-neck with its main rival, ARY Digital. It has consistently produced hit, including some of last year’s biggest shows Aangan, Alif Allah aur Isaan, and Dar si jati hai Sila.

How did this television channel get there? How has Hum TV consistently produced some of the best television content in an industry that is inundated with competitors? And, while we are on the subject, how has the company’s television networks managed to survive the real-life drama that took place in the early part of this decade for the control of Hum Networks?

The story begins with a person who can rightfully be called the dean of Pakistani entertainment: Sultana Siddiqui.

The origins of Hum Networks

Sultana Siddiqui is the sister of investment banker and financier Jahangir Siddiqui, and while having her elder brother be a billionaire certainly helped Sultana launch her network, she had become a credible force in the entertainment world in her own right through her long career at the state-owned Pakistan Television (PTV), which she joined as a producer in 1974.

Prior to joining PTV, however, Sultana’s life had taken a tragic turn. She had gotten married in 1966 and had three children with her husband, but the marriage, for a variety of reasons, did not last and being a divorcee in 1960s Pakistan came with a fair number of hardships, even with the kind of support Sultana found in her brothers.

The Siddiquis are a highly educated middle-class family, with a long history of government service. Sultana’s father was in the civil service in Sindh. They are also a close-knit family who particularly came through for Sultana during her separation from her husband and ultimately her divorce. Her elder brother Mazhar, in particular, was a father figure to her children, and Jahangir, the financier, helped ease her financial worries.

The job at PTV was one she found out about through a college friend, and one that ended up becoming a significant portion of her life’s work. Sultana started off in Sindhi programming at PTV, before moving into Urdu programming in 1981. She had a long career at the state-owned broadcaster, effectively the monopoly on entertainment in Pakistan until 1992, when the government began experimenting with allowing a private company permission to run a portion of the day’s programming on one of the state-owned channels (NTM, for those of you who remember it.)

It was not until 2001 under the Musharraf Administration that the television industry in Pakistan was full liberalised (at least insofar as ownership was concerned) and it was around that time that Sultana began contemplating starting her own television network.

By this time, Jahangir Siddiqui was one of the richest men in Pakistan, and certainly one of the richest self-made billionaires in the country. He was in a comfortable position of being able to help Sultana launch her television network, much as he had been able to help his nephews – Sultana’s sons – launch other businesses over the years.

In 2004, Sultana was ready to pull the trigger. She launched her entertainment network with the name Eye Television (later renamed Hum Networks), and the company was listed on the Karachi Stock Exchange shortly thereafter. (Did we mention her brother was an investment banker?)

Pakistani television, and Hum’s business model

Television is a difficult business because you have to keep producing shows that have audience appeal. Unlike shows in the US and UK, where good shows often run for multiple seasons, Pakistani shows are effectively all designed to be single-season shows of varying lengths, with one story arc dominating the entire season and the show concluding when that arc ends. That means there is much higher turnover in shows, and therefore much less predictability in terms of whether or not a channel will be able to produce content that people will like.

It also means more financial instability for the actors, producers, directors, scriptwriters, and other staff who are involved in the production of television shows. They do not know where their next paycheck will come from once the show they are working on ends.

Hum Networks succeeded by attracting the best talent, which it did by solving the financial insecurity problem for people who work in the television business. In addition to the publicly listed Hum Networks, Sultana and her family also own Moomal Productions (now renamed MD Productions), a private production house that have an exclusive contract to produce content for Hum TV, the company’s main entertainment television channel.

Because they have guaranteed uptake of their shows, Moomal has a habit of granting multi-show or multi-film contracts to actors, directors, writers and other talent. Thus, even though shows last for a single season, Moomal is able to hire people for longer, giving talent more predictability and Moomal (and by extension, Hum TV), the ability to attract some of the best talent in the industry.

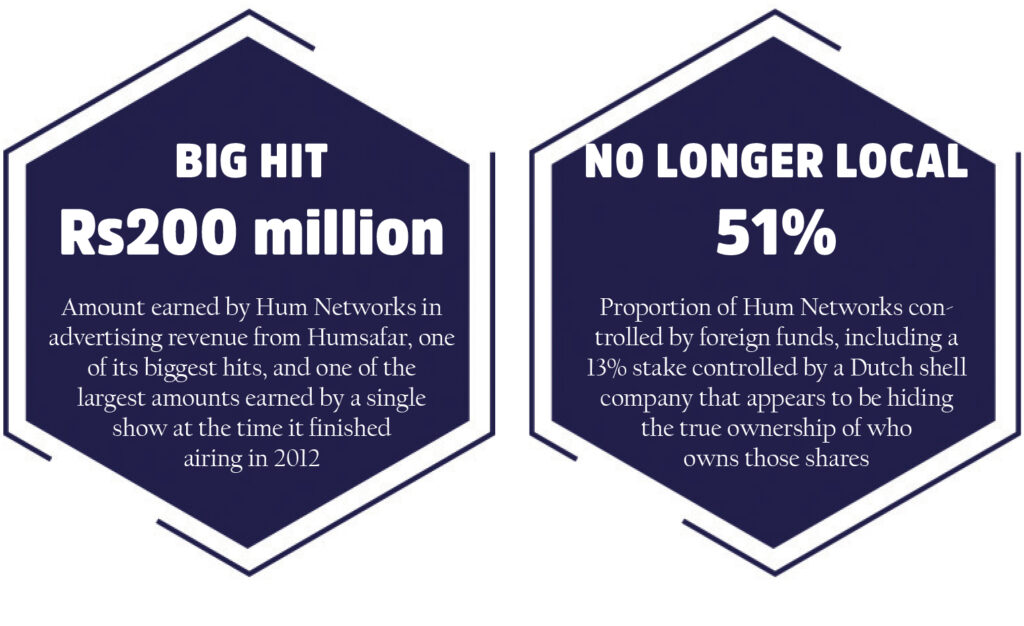

The dramas it has produced have generated an audience beyond Pakistan and the company syndicated the 2011 show Humsafar, its biggest hit drama and the biggest ever in Pakistani television history, to an Indian channel. Humsafar generated Rs200 million for the company in revenue on its first television run, the highest for any Pakistani television show until that time, and in the syndication deal, it earned even more.

Hum TV is also a highly innovative company, having effectively invented the uniquely Pakistani style of drama, as opposed to cheap knockoffs of Indian shows that used to dominate the industry prior to its arrival. Sultana Siddiqui and Momina Duraid (CEO of Moomal Productions and Sultana’s daughter-in-law) are gutsy women and they backed risky shows in the early years even when they were not able to get ads for them, including shows that address previously taboo topics.

One of its earliest shows was a drama called Meray pass pass, in which a couple get into dispute over a pregnancy. The husband wants to abort, the wife does not, and so the husband leaves her. A neighbour, who is younger than the wife, starts becoming friendly with her and the two of them start having an affair, resulting in a divorce with her husband and marriage to the neighbor.

Another was called Maanay na ye dil, a story of a white-collar worker falling in love with a high-priced call girl. These shows established Hum TV’s brand and allowed it to command a premium over its competitors in the rates it charges its advertisers.

Hum TV’s primary revenue stream – advertising by consumer goods companies – is a play on one of Pakistan’s strongest macroeconomic themes of an expanding consumer middle class.

And having its own production house does not mean that the channel is precluding working with talent not directly employed by Moomal. “There is a plethora of production houses and Hum still buys a lot of content from the market,” said the CEO of a rival media house who wished to remain anonymous.

But Hum’s unique business model, coupled with the success it had in not just attracting talent, but then also being able to generate strong revenue and profit growth from that talent, resulted in several of its competitors seeking to emulate its business model.

In April 2013, for instance, Geo Entertainment entered into an exclusivity agreement with A&B Productions, one of the most prolific television production studios in Pakistan and second only to Moomal. It produced popular shows such as Mein Abdul Qadir hoon, and Meri Saeen. A&B used to be a content provider that sold its shows to Geo, ARY, and Express Entertainment before entering into the exclusivity agreement with Geo Entertainment.

Family drama and the battle for control

For a company that makes its money off of selling family dramas as its bread and butter, the battle for the control over Hum Networks has also been quite dramatic. And like most good Pakistani dramas, it involves family, unspoken norms about money, and a bit of betrayal.

The following account is based on conversations with two sources familiar with the Siddiqui family’s dynamics, as well as an on-the-record interview with Aqeel Karim Dedhi, known colloquially by his initials AKD, Jahangir Siddiqui’s main rival in the battle for dominance over the Karachi Stock Exchange (now called PSX).

As mentioned earlier, after Sultana’s divorce, her eldest brother Mazhar had served as a father figure for her children, and Jahangir had been a source of financial support for the family as a whole. Jahangir is easily the wealthiest of the siblings, since the Siddiquis were not previously a wealthy family.

Jahangir’s support for his sister’s family went above and beyond simply ensuring that their basic financial needs were provided for. According to sources familiar with the matter, Jahangir’s support often entailed substantial support for Sultana’s sons’ business ventures, which had – over time – enabled them to become wealthy individuals themselves.

This financial support lasted for decades, but after some time, particularly as Jahangir himself stepped back from his businesses and other managers, led by his sons, took over the companies that were the source of that financial support and slowly started tapering it down, particularly since Sultana’s sons no longer really needed it, being themselves largest shareholders in at least two publicly listed companies – Hum Networks and Al-Abbas Sugar Mills.

Sources familiar with the matter say that this change in the financial dynamics of the family were not welcomed by Shunaid Qureshi, Sultana’s elder son, who had been a particular beneficiary of Jahangir’s support. (Shunaid was, at one point, the largest shareholder in both Hum Networks and Al-Abbas Sugar Mills.)

Jahangir and his family, however, did not quite realise just how upset Shunaid was, or just how reliant he was on that support, until the early part of the Zardari Administration, when Jahangir Siddiqui got into a very well-publicised spat with thugs in Karachi allegedly acting at the behest of the former president, who tried to take control over a property owned by one of Jahangir’s brothers. Jahangir tried to intervene and ended up allegedly incurring the wrath of the former president, and for a time went into self-imposed exile in Dubai.

He was able to return after his daughter married the son of Mir Shakilur Rahman, the owner of the largest news network (Geo News) and Urdu newspaper (Daily Jang) in Pakistan, as well as a rival entertainment channel, Geo Entertainment. Some observers believe that the marriage served to provide the backing of Pakistan’s largest news network as an insurance policy against political harassment by the government for Jahangir Siddiqui.

Soon after the marriage, Jahangir appears to have had a falling out with his sister. That there was a dispute between Sultana and her brother is not disputed by either party. What is disputed is the cause.

In the telling of sources familiar with Jahangir’s side of the story, when Jahangir returned to Pakistan, he found that Shunaid had been embezzling money from Al-Abbas Sugar Mills, in which Jahangir Siddiqui & Company was still a major shareholder. Jahangir quietly confronted his nephew about the matter and asked him to replace the money allegedly embezzled.

Shunaid, in this telling of the story, already smarting from the earlier cut off of financial support, far from replacing the money, went on the offensive, accusing Jahangir’s son Ali of embezzling money from Jahangir Siddiqui & Company, a publicly listed company.

But while Jahangir Siddiqui & Company eventually filed a lawsuit in April 2013 against Shunaid and his alleged co-conspirators, it is unclear if Shunaid and his allies ever filed a counter-suit. The accusations against Ali Jahangir were publicized in a pamphleteering campaign at the headquarters of the Karachi Stock Exchange.

The other telling of the story – more sympathetic to Sultana’s viewpoint – tells a completely different tale. As narrated by AKD, Jahangir was able to return to Pakistan because Mir Shakilur Rehman offered “protection” to his son’s new father-in-law through the power of his news media empire, but in exchange demanded control over Hum TV, the only television network that consistently beats Geo in the ratings and in revenue.

As AKD puts it, Jahangir tried to buy out his sisters shares in a bid to hand over control over Hum Networks to his daughter’s new in-laws. In AKD’s telling, Jahangir was practically forcing Sultana to sell her shares to him against her will, a move she was not willing to make. Dedhi claims that she then came to him to orchestrate a defense against a possible hostile takeover.

There is one problem with this narrative, however: Jahangir Siddiqui & Company sold some of its shares in Hum Networks, reducing its shareholding from 18% to 14% in 2010 and does not appear to have made any attempts to increase its shares in Hum Networks since then. Shareholding patterns of publicly listed companies are a matter of public record.

What is clear, however, is that Jahangir was absolutely miffed at the idea of his sister approaching his rival for takeover defence. This led to a series of escalating accusations by JS & Company and Shunaid against each other in the press, including one incident in which Shunaid walked into a shareholder meeting of JS & Company and tried to incite a small boardroom riot. Television cameras present at the event actually recorded Shunaid ripping his own shirt to make it look like he was attacked.

The truce and foreign investors

After that very public falling out, however, tempers appear to have finally calmed down enough for both sides to have ultimately arrived at what appears to be a truce: there are no more public accusations of wrongdoing against each other. And control of the company appears to have been passed on to neutral third parties: a group of foreign investors.

According to the latest financial statements of Hum Networks, a group of 19 foreign investment funds together control 51% of the company’s shares. The largest of these is the London-based Kingsway Fund, which owns 16.3% of the company. A Dutch shell company owns another 13.2%.

One change that has come about since the battle was over: Hum Networks is moving to formally acquire Moomal Productions to have the entirety of the business under a single holding company.

Sultana takes a back seat, but retains control

Moomal Productions is run by Momina Duraid, Sultana’s daughter-in-law. Both of them are capable women who have a clear sense of what direction to take the industry in and a demonstrated ability to turn that vision into a financially profitable business.

“Sultana Siddiqui used to be involved in running the day-to-day affairs of the company, but she has since taken a back seat. She is still involved in all the major decisions, of course. Like, for example, if they were to hire a senior manager, she would probably come in for that,” said one source familiar with the matter.

“They have not really cut her out of the business. They can’t. She is very well respected in the industry because of her PTV [Pakistan Television] days. She has all the contacts they would need, including at PEMRA [Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority] and the like. She adds a lot of value. She may not be involved in the everyday running of the business anymore, but she still has a veto over key decision,” the source continued.

“Momina ultimately has to answer to Sultana, because Sultana is still very much the creative head. It’s not about what Duraid [CEO of Hum Networks, and Sultana’s younger son] wants. It’s about what Sultana wants. So yes, Momina has creative control over Moomal Productions [since renamed to MD Productions] but she works closely with Sultana on that,” the source said.

The next phase of growth

Hum Network wants to move beyond just its commanding position in entertainment to becoming a bigger television company. In 2017, the company spent Rs1.3 billion in setting up a new channel – Hum News – to compete in the already highly competitive television news business.

The timing, however, could not have been worse: soon after the channel was set up, the Imran Khan Administration came into office and slashed the government’s advertising budget. The federal and provincial governments are the biggest source of advertising revenue for television news channels and the print media, accounting for up to a third of revenues for the industry before the recent cuts.

Meanwhile, even though Hum TV remains a strong force in television entertainment, ARY has remained a tough competitor that continues to churn out strong content, including this year’s breakaway hit, Cheekh.

On the digital front, Hum Networks appears to be following the route of many US television studios and leasing its content to paid streaming services such as Netflix as well as making them available on free streaming websites like YouTube. Digital advertising is continuing to grow, and over time the revenue from YouTube and Netflix may grow into a more meaningful portion of Hum’s business.

Hum Networks’ revenue is down only 8.7% at a time when much of the rest of the industry has seen losses considerably greater than that, especially rival networks Geo and ARY, which were much more dependent on government advertising revenue for their news channels.

Ultimately, even though the stock is currently in the doldrums right now, it is likely unwise to bet against Hum Networks. Any company that builds its business model on treating its employees well, and ensuring greater financial security in an industry known for lacking such security is likely to continue to attract high quality talent that is likely to offer its best work. And ultimately, that is likely to remain successful with the viewing audience.

HUM TV channel produces very nice and awesome dramas.HUM channel achieve big success in very short time

why hum network shares down and down in stock market… completely disaster…. lowest price trade around 3 rulees in 2019 … any chance to bounce back … bcz couple of years humnetwork high price 177 … but this time this item is KACHRA . language of stock …

I neend jon

Comments are closed.